Читать книгу Contempory Netsuke - Miriam Kinsey - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

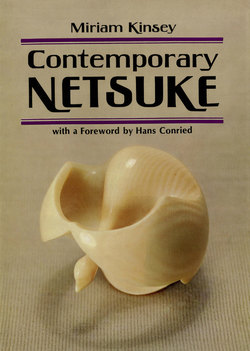

Contemporary Netsuke

EVALUATION

Comparisons may be odious, but they are inevitable when evaluating netsuke. In the following explanation of comparative areas in the quality of contemporary and antique netsuke, it must be understood that, unless otherwise noted, only first-class netsuke are considered. These are all issaku netsuke, executed completely by one person—the design, the rough carving, the final work, and any color, stain, or inlay that may be added. The cheaper, mass-produced work is called bungyo, or division work, with the rough carving (arabori) being done by one person and the final work (shiage) by at least one other—all from a design furnished by the “manufacturer," dealer, or agent.

Quality might be defined as “the natural or essential character of something'' as well as “degree or grade of excellence.” Basically, the evaluation of netsuke involves quality of design and subject matter, material, and workmanship.

DESIGN AND SUBJECT MATTER

Design has been said to be the soul of netsuke, but in the eighteenth century, as the use of netsuke spread to all classes and these small carvings began to be regarded as status symbols, excellence of material and workmanship grew in importance.

The early artist-carver was forced by the functional nature of the netsuke to observe certain restrictions in design. Since it passed between the obi and the hip, the netsuke had to be small and rounded, without sharp edges or jutting points that could catch in the kimono material. Its form must not be damaged by the friction involved in its use. Actually, this rubbing often developed a patina (aji) that helps in the authentication of an antique netsuke and adds to its beauty. The netsuke had to be sturdy enough to support the hanging object by the cord passing through it. The cord holes (himotoshi) were made on the side to be worn next to the body so as not to detract from the design on the front. Even the early functional netsuke, however, were so designed and carved that they were complete in every detail on all sides and usually could stand with perfect balance when not being worn.

The netsuke being produced today have no functional restrictions in design. A protruding cane, a lacy leaf or flower, or sharp stylized lines are no longer precluded and often lend a charm and freshness to the design. However, the netsuke purist may say, “This is not a netsuke. It is a piece of miniature sculpture. It hasn't the feeling of a netsuke.” This is an ongoing argument among collectors. Contemporary netsuke carvers also differ on this point. The majority of them adhere to the old fundamental concept in design. Their netsuke are smooth and rounded and have a “good feeling." Others take advantage of the freedom from functional restrictions and produce what actually is sculpture in miniature, or a diminutive okimono, sometimes not even adding the himotoshi, long the hallmark of a netsuke.

Subject matter will be discussed at greater length in another chapter. In general, however, today's netsuke, like the antique examples, draw from the natural world of flowers, insects, and animals, as well as the vast reservoir of Japanese folklore, history, literature, religion, theater, customs, and social life. Perhaps because of the taste of Western collectors, many animal subjects are found among contemporary netsuke (Figs. 4-23, 25, 26). The legendary figures in contemporary netsuke tend to be somewhat more representational than the exaggerated versions—“grotesqueries," as they are sometimes called—so often found among antique netsuke.

Occasionally a contemporary netsuke bordering on the abstract can be found. “Stylized” might be a more accurate description of this type, or “netsuke with deformations," to use an expression of one of the contemporary carvers (Figs. 26-28). Stylized or abstract, they remain distinctly Japanese.

Although color on wood goes back to the early netsuke of Shuzan (mid-eighteenth century), extensive use of color on ivory began in the twentieth century with Ichiro, who, like many Japanese craftsmen and artists in various fields, was trained as a painter. The general use of color and stain in the netsuke being produced today adds a decorative and vital touch that accentuates the design and helps to bring the little figures to life.

When viewing representative collections of first-rate antique and contemporary netsuke, a person unfamiliar with netsuke art usually remarks that the contemporary netsuke figures seem happier, more pleasing, and less strained and distorted than most antique figures. Some of the carvers today explain this difference by pointing out that in earlier days the carvers were members of the lowest social class. During the Edo and Meiji periods, they felt unhappy and oppressed, and their struggles were often reflected in their art. Today, there is no class distinction. First-rank carvers are beginning to receive recognition for their work, and life in general for the carver and his family is fuller and happier. And undoubtedly the fact that amateur collectors are usually more attracted to pleasing, beautiful netsuke has also had an influence on the basic design attributes of contemporary netsuke figures.

With a lower standard of living as well as lower living costs, carvers of old found that time was of little value. Often months were spent by a carver in producing a masterpiece. Today, because of economic demands and the pressure of unfilled dealers' orders, there is usually a time limitation on the contemporary carver. He feels that this is compensated for by the opportunity he has to develop his talent through study and through the exchange of ideas and techniques. The carvers of antique netsuke often had their own special techniques or workmanship devices, which were closely guarded secrets. This is no longer true. Today there are few, if any, secrets in the techniques of netsuke carving and coloring.

A greater variety of subjects and materials is to be found in antique netsuke than in the contemporary pieces, largely because there are comparatively few first-rate netsuke being produced today. No area of design has been neglected, however, and a specialized collector can always find his own particular subject preference in contemporary netsuke.

Pages from Hokusai's sketchbooks and others, as well as crumpled and worn sketches done by a teacher or a teacher's teacher, can be found in the work-rooms of many contemporary carvers. Bookshelves contain volumes on Japanese history and religion, the Noh and the Kabuki dramas, folklore, and legend. An unspoken commitment seems to exist among living artist-carvers to preserve the netsuke as an art form that unlocks the treasures of the whole gamut of Japanese life and culture.

MATERIALS

When decorative, carved netsuke became accessories of attire early in the seventeenth century, the material generally used was wood: cypress (hinoki), which was soft; boxwood (tsuge), a very hard wood used for more detailed, intricate carving; and many other varieties, including bamboo, yew, black persimmon, mulberry, tea shrub, cherry, and pine. Some carvers also selected Chinese ebony, camphor, and other imported woods.

Ivory was first used by netsuke carvers during the latter part of the seven-teenth century, when the shamisen became a popular musical instrument among all classes. Its plectrum was made of ivory, and after the plectrum material had been taken from the elephant tusk, the remnants were made available to netsuke carvers. The fact that these pieces were three-sided accounts for the somewhat triangular shape of many of the netsuke of that period. The better carvers shunned these remnants from the shamisen factories and used only the finest quality of ivory (tokata), preferring Siamese and Annamese tusks. Although elephant ivory was the first choice, netsuke carvers also used boar and hippopotamus tusks as well as those of the narwhal and the walrus, often called marine ivories. A highly prized but very rare type of ivory, reddish orange and yellow in color, was that which came from the protuberance around the huge bill of a tropical bird called the hornbill.

Horn was a frequently used material. Staghorn, which actually was antler rather than horn, was preferred, but netsuke carved from water-buffalo and rhinoceros horn are in existence, although rare.

During the early years when netsuke carving was largely a side industry of craftsmen in other art areas, or a hobby of dilettante carvers, many materials—and combinations of materials—were used: agate, jade, coral, amber, marble, porcelain, various metals (usually combined with wood or ivory in the bun-shaped netsuke called kagamibuta), woven reeds, and lacquer. As the demand for netsuke increased and netsuke carving became a vocation for many carvers, the variety of materials decreased, and most of the netsuke produced in the nineteenth century were of wood or ivory.

With the end of the netsuke as a functional part of Japanese attire and its emergence as an export and collector's item, ivory became the popular material for these little art objects. This continued until the World War II years, when luxury materials like ivory were not available. Most of the carvers were then either in military service or working in factories, and the few netsuke carved in their spare time were fashioned in wood.

Today there are not over two or three netsuke artist-carvers who work exclusively in wood, although several who generally carve in ivory make an occasional wood netsuke. It would be safe to say, however, that over eighty percent of contemporary netsuke are ivory. Mother-of-pearl, semiprecious stones, and bits of gold and other metals are sometimes used for inlay and decorative purposes. Stain and color are applied quite extensively and always by the artist himself.

First-rank carvers are always concerned about the quality of their netsuke ivory. Fine-grained, lustrous ivory has a tactile quality sought and enjoyed by collectors. Even in stained or colored netsuke, the crossing, reticulated lines of fine ivory are usually distinguishable.

The greater portion of ivory imported into Japan today comes from the Congo, although much also comes from other African areas—Kenya, Zanzibar, Tanganyika, Uganda, South Africa, Mozambique, Zambia, and Nigeria. Ivory from the Congo is the hardest of African ivory, but ivory from India, Thailand, and Cambodia is still harder. Since India and Thailand are now protecting their elephants, ivory from those countries is sold only locally and is no longer exported. It should also be noted that under the Endangered Species Act of 1973 the United States cooperates with the international community in protecting animals threatened with extinction and that any ivory netsuke shipped to or from Japan must be accompanied by a guarantee that the netsuke is made of ivory from an elephant legally killed in the country of origin, which country must be named in the guarantee. The harder ivory is preferred by most netsuke carvers, but soft ivory can be used for fifteen-or sixteen-inch okimono.

Since trade restrictions against Communist China have been relaxed, Chinese ivory carvers are making jewelry and various types of decorative figures for the tourist trade. Recognizing the potential in this business, the Chinese government has begun to import ivory for their carvers. This, among other reasons, has caused a sharp rise in the price of ivory in Japan. In fact, the price more than doubled between 1969 and 1971 and has continued to rise.

There are three companies directly importing ivory to Japan: Miyakoshi, Kitagawa, and Kita. Ivory manufacturers, netsuke agents, or dealers can buy tusks at any time, but when the importers are overstocked, they sell at auction. Normally, ivory auctions take place once or twice a month. Usually, a whole tusk must be purchased, but occasionally some "points" (pointed ends of tusks) appear at auction when the African exporter has sent the poorer parts of tusks to other countries and only the points to Japan.

Tusk points are usually bought for netsuke carving and are 50-70 centimeters (20-28 inches) in length. The fine-grained, hard ivory comes from this part of the tusk, which is solid. At the larger end of the point, a slice can sometimes be cut into three triangular pieces for three netsuke. The middle part of the tusk, also solid, can be used for large figures and an occasional netsuke. The bottom, or large end of the tusk, is hollow and can be used for some types of okimono as well as for chopsticks, flowers, or accessories. No part of the tusk is wasted.

Netsuke material must be of high grade, and sometimes there will be no ivory of netsuke quality in a whole tusk. Dealers and agents who furnish ivory to their carvers often buy netsuke ivory from shops or manufacturers of chopsticks, jewelry, flowers, and other ivory articles. Since these items do not require top-grade ivory, the good ivory can be saved and resold for netsuke carving.

Some merchants import ivory and hire carvers to produce all kinds of ivory pieces: jewelry, flowers, fruit, okimono, and other decorative pieces, as well as netsuke, for their own shops in Japan or to sell to other local or foreign dealers. All ivory must be hand-carved, and every carver has his specialty. All ivory work is done by the carver in his own home, and the merchant-importer has both first-rank artist-carvers and division (bungyo) carvers working for him.

The latter carvers are craftsmen—many of them highly skilled—who make the inexpensive netsuke found in shops and stores all over the world, as well as in shops throughout Japan. These netsuke, usually carved from models supplied by the employer, lack the originality and the time-consuming, meticulous attention to detail that are found in the first-rank carvers' work. But they are hand-crafted, typical Japanese mementos that the tourist, the person not yet “hooked" on serious netsuke collecting, or someone who cannot afford the higher cost of the better contemporary netsuke, can easily carry, keep, handle, and enjoy.

WORKMANSHIP

Japan is a small, insular country. The prewar Japanese were generally small-boned and small in stature. Their penchant for artistic expression on a small scale and their digital skill can readily be seen in the development of such art forms as sword furniture and netsuke carving.

Toggles and handicraft articles somewhat similar to netsuke have been found in other countries, but the scrupulous, skillful workmanship and the delicate and precise carving of netsuke are virtually unknown outside of Japan.

Time meant little to the early carver. Days, weeks, or months went into the making of a netsuke masterpiece. As any craftsman knows, the task of reducing elaborately ornate or abstractly simple designs to an incredibly small scale requires infinite patience and time as well as great skill and talent. Unfortunately, with the extremely high cost of living in Japan today, time is no longer an expendable component of netsuke making. Due to pressures from dealers and economic demands, occasionally there is quite a spread in the quality of the work from a first-rank carver. In short, in addition to his first-rate netsuke (which may include true masterpieces) there may be pieces that obviously have taken considerably less time to produce or for other reasons are below the capability of the carver.

Two questions are often asked by collectors or potential collectors: “Does the contemporary carver use any power tools for rough work or for polishing?" and “How does the workmanship of a first-rate netsuke carved today compare with that of antique netsuke?"

A few first-rank carvers today own dental drills which they use very sparingly on less than ten percent of their total work. A few also make limited use of an electric polisher. In this connection, it must be remembered that over one hundred years ago some netsuke carvers employed lathes, although these tools were simple and rough. The majority of living carvers use no power tools; they carve with self-made tools and hand-polish their netsuke. The various facets of the workmanship involved in the making of a netsuke will be explored in detail in the following chapter.

Comparison of contemporary and antique netsuke involving comparable techniques will compel even the most prejudiced antique-netsuke collector to admit that the workmanship of some of today's first-rank carvers is fully as admirable as that of the early masters. The absence of functional restrictions often takes a contemporary carver into highly imaginative, intricate designs, involving delicate, exquisite workmanship and the display of craft techniques that cut across various traditional professional schools.

The world in which the netsuke carver lives today is very different from the world of the old masters. But the spirit and the technical skill of the early carvers is splendidly alive in the first-rank contemporary carvers.

4. CUTTLEFISH IN A BASKET. Wood and ivory. Signed: Sosui. Date: 1945. Sosui's incomparable technique in this netsuke is so skillful that the basket actually appears to have been woven. The quiet design, involving the contrast of ivory on wood, and the high technical proficiency combine to make this one of his finest netsuke. Several years ago, when Sosui was asked to indicate his favorite netsuke subject, he replied, "Cuttlefish in a basket." (Enlargement: 2.0 times)

5. OTTER. Wood. Signed: Sosui. Date: 1930-50. Sosui's love of animals is clearly apparent in his carving of an otter on a log, about to eat a fish. This is a rare subject in netsuke. The elongated form of the animal has been naturally positioned on the gracefully carved log in such a manner as to preserve, unobtrusively, the functionalism of the netsuke. (Enlargement: 1.7 times)

6. BADGER AND "EARTHQUAKE" FISH. Wood. Signed: Shinzan. Date: 1968. Shinzan's beautifully carved double-figure netsuke depicts a mujina (a type of badger) and a namazu (catfish, associated with earthquakes because it is so active before they occur) locked in a furious struggle. The convolutions of the two animals have made possible a netsuke design of true functional form. (Enlargement: 1.3 times)

7. THE TWELVE ZODIAC ANIMALS. Ivory. Signed: Meigyokusai. Date: 1960-70. The twelve zodiac animals are the subjects most frequently portrayed in netsuke: rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, serpent, horse, sheep, monkey, cock, dog, and boar. They are usually carved individually, but occasionally artists have undertaken the difficult task of presenting the entire group in a single netsuke. Meigyokusai is one of the few carvers to succeed in the feat, and his netsuke is both a marvel of workmanship and a design of rare beauty. (Enlargement: 2.0 times)

8. CLUSTER OF RATS. Ivory. Signed: Kangyoku. Date: 1965-70. The rat is the first sign of the Oriental zodiac. Rats are symbols not only of good luck but also of wealth and prosperity because of their association with Daikoku, god of wealth, whose servants they are. By skillfully carving seven rats in a cluster, Kangyoku has preserved traditional functionalism in this netsuke. His use of light and dark ivory not only lends interest to his carving but also evokes yin-yang connotations. (Enlargement: 1.6 times)

9. WILD BOAR. Ivory. Signed: Kangyoku. Date: 1960-70. The boar, one of the twelve zodiac animals, is regarded in the Orient as a symbol of utmost courage, strength, speed, and ferocity. With no thought of self-protection, it hurls itself straight at its enemy. The hollow log through which Kangyoku's boar is charging seems to have a double purpose. It preserves the functional and tactile qualities of this uniquely designed netsuke. It also serves as a reminder that a tree may be the safest haven for a hunter when charged by a wild boar. (Enlargement: 1.5 times)

10. MANDARIN DUCK. Ivory. Signed: Sosui. Date: 1940-60. The mandarin duck (oshi-dori) symbolizes connubial devotion and is a favorite subject among Oriental artists, including netsuke carvers. The gentle, peaceful character of the bird supports an ancient legend that the Buddha was once reincarnated in the form of a mandarin duck in order to teach mankind its spiritual virtues. Sosui's abstract concept of this subject is simple and quiet, and the wings suggest the fan shape of the gingko leaf. (Enlargement: 1.5 times)

11. RABBIT. Ivory. Signed: Kangyoku. Date: 1970. The fourth sign of the Oriental, zodiac, the rabbit, is frequently found as the subject of netsuke. One of the best examples is this somewhat stylized design of Kangyoku's, which he calls his “jewel" rabbit. (Enlargement: 1.6 times)

12. COCK. Ivory. Signed: shinryo. Date: 1965-70. Shinryo's highly stylized, almost abstract treatment of the cock is noteworthy in its tactile quality as well as its design. The cock, or rooster, is the tenth sign of the Oriental zodiac, and for that and many other reasons it is an important art symbol in Japan. Fortunetellers say that persons born in the year of the cock are generally intelligent and kind by nature. Their other qualities include protective faithfulness, courage, and prosperity. (Enlargement: 1.4 times)

13. ALIGHTING SWAN. Ivory. Signed: Bishu. Date: 1971. Bishu's alighting swan is one of the most beautiful and imaginative netsuke ever carved. With great skill and originality, the artist has captured the elegant grace of the swan's fleeting motion as it touches the water. (Enlargement: 2.3 times)

14. SQUIRRELS. Ivory. Signed: Kangyoku. Date: 1971. During a discussion of our mutual love of household pets and wildlife, Kangyoku was shown a photograph of pampered squirrels at play on the patio of our California home. At our next meeting, some six months later, Kangyoku proudly displayed this superb squirrel netsuke. (Enlargement: 1.8 times)

15. PUPPY CHEWING ON A STRAW SANDAL. Ivory. Signed: Kangyoku. Date: 1972. This netsuke of Kangyoku's is a vivid portrayal of canine mischief. It is shown in its various stages of carving in Chapter 6, Figs. 130(a)-(p). (Enlargement: 1.7 times)

16. ROPE RABBIT. Ivory. Signed: Bai-shodo (see biography of Bishu, p. 214). Date: 1968-71. This is a unique design. The abstract form of a rabbit has been achieved by coils of rope. Adding further interest is a rat, which has built its nest in the rope and appears and disappears at an opening in the rabbit's ear. Trick netsuke of this type have been common for centuries, but this particular design, involving two of the zodiac animals, has special charm and interest. (Enlargement: 1.5 times)

17. CICADA ON BAMBOO. Ivory. Signed: Senpo. Date: 1971. The fragile beauty of the cicada has always fascinated the Japanese, and its mystique has been beautifully captured by Senpo in his portrayal of the insect at rest on a bamboo stem. The cicada in Oriental legend was a symbol of immortality, and a jade cicada was always placed on the tongue of a deceased Chinese emperor when he was buried. Here Senpo has succeeded remarkably well in simulating the shiny, smooth texture of bamboo. (Enlargement: 1.3 times)

18. RAM. Wood. Signed: Shinzan. Date: 1960-70. Although the sheep (or goat) is one of the twelve animals of the Oriental zodiac, sheep were unknown in Japan until they were introduced by the Europeans. For this reason, rams, as they are portrayed in netsuke art, are often indistinguishable from goats. Shinzan's carving of this subject displays his characteristic sensitivity. (Enlargement:1.5 times)

19. BLOWFISH (FUGU). Ivory. Signed: Ryoshu. Date: 1971. One of the delicacies that most delight the Japanese palate is the raw flesh of the blowfish, or globefish (fugu), which is served in tiny paper-thin slices, often beautifully arranged in the pattern of a chrysanthemum or a crane. But if improperly prepared, the fugu is highly toxic. Ryoshu's netsuke is an interesting, stylized portrayal of this subject. (Enlargement: 1.5 times)

20. GROW. Ebony. Signed: Sosui. Date: 1950-60. The crow is relatively rare as a netsuke subject, and this highly stylized version of Sosui, s, fashioned as a whistle, is quite reminiscent of some of the decorative art of the Alaskan Indians. According to some Japanese, the crow is a symbol of filial piety. It also makes its appearance in folktales and legends of the supernatural, sometimes auspiciously and sometimes ominously. (Enlargement: 1.6 times)

21. FROG. Ivory. Unsigned: carved by Clifton Karhu. Date: 1970. This amiable frog successfully reflects a glint of worldly wisdom and inscrutable inner contentment that are somewhat reminiscent of the twelfth-century Choju Giga Emaki, or Scroll of Frolicking Animals. Clifton Karhu is an American in Kyoto whose manifold talents have centered primarily on woodblock prints. This frog is one of his earliest and most successful excursions into the field of netsuke carving. There is no expectation that Karhu will concentrate in this field, but his avocational experiments may well lead to further achievement. (Enlargement: 2.2 times)

22. MOTHER AND BABY MONKEY AND A PEACH. Wood. Signed: Soko Morita (Somi). Date: 1920-30. Courtesy of Virginia Atchley. The monkey is the ninth sign of the Oriental zodiac and, according to Taoist legend, is the bearer of the sacred peach of immortality. Here the mother monkey is eating a peach, and the baby is trying to get it away from her. Soko's talents were at their zenith when he designed and carved this netsuke. (Enlargement: 2.1 times)

23. HORSE. Ivory with inlaid eyes. Signed: Kangyoku. Date: 1972. Horses have very sensitive stomachs and more often die of colic than of any other disease. When in pain, a horse often tries to bite its hind quarters or its tail, assuming the unnatural position here portrayed by Kangyoku. The flattened ears, bared teeth, bulging eyes, and contorted body in this skillfully carved netsuke clearly depict a suffering horse. Like most of Kangyoku's netsuke, this one combines contemporary design with the functional form and tactile qualities of antique netsuke. (Enlargement: 1.7 times)

24. HORSE AND GROOM. Wood. Signed: Sosui. Date: 1930-50. The horse is the symbol of the seventh year of the Oriental zodiac and is represented throughout Japanese art with a great variety of symbolic and legendary associations. Sosui's love of animals, and nothing more, seems to be conveyed by his simple figure of a horse being groomed by an attendant. (Enlargement: 1.9 times)

25. WHITE INARI FOX. Ivorv. Signed: Keiun. Date: 1965-70. Every local community in Japan has a shrine dedicated to the harvest god Inari. In front of most Inari shrines are the images of a pair of foxes regarded as messengers of the god. The beneficent white Inari fox, portrayed in this classic design by Keiun, is to be sharply distinguished from the evil field foxes and demoniac foxes often encountered in Japanese legends. (Enlargement: 1.5 times)

26. RABBIT. Ivory, Signed: Kangyoku. Date: 1971. This engaging rabbit netsuke was conceived by Kangyoku in a mood of free fantasy. It is a masterpiece of design and execution. The carving and finishing of the ivory have produced beauty and satisiying tactile qualities. The design is original and daring and has strong appeal, except to the most conservative traditionalists. (Enlargement: 1.4 times)

27. SHISHI. Ivory. Signed: Kangyoku. Date: 1971. This carving is Kangyoku's first excursion into the realm of the abstract. It proved to be eminently successful. The subject matter and functional form of the netsuke are completely orthodox, but the design is modern. Many netsuke collectors have been surprised but delighted with the bold, imaginative design of this shishi. (Enlargement:1.5 times)