Читать книгу Baleen Basketry of the North Alaskan Eskimo - Molly Lee - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

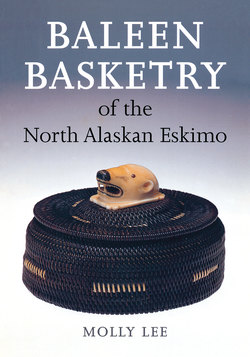

For more than half a century, Eskimos1 of North Alaska2 have made baskets of baleen, the keratinous substance from the mouths of plankton-eating whales. Never as widespread as ivory carving, baleen basketmaking has nonetheless contributed significantly to the livelihood of its practitioners in the arctic villages of Barrow, Point Hope, Wainwright, and Point Lay, Alaska. But today, like the arts of so many small-scale societies, baleen basketry faces extinction. The main intent of this investigation, therefore, was to make a permanent record of the art form while its few remaining practitioners were still alive. But the study had a second aim as well. Almost fifty years have passed since the first baleen basket was collected by a museum, yet in the interim there has been no thorough description and analysis of them. The explanation for this neglect is simple. Baleen baskets are a so-called tourist art,3 made by Eskimos for nonnative consumption (Graburn 1976a); because of their hybrid and commercial associations, investigators have habitually spumed4 such arts. Their collective disdain is distilled in one museum curator’s response to a baleen basket collection offered him for purchase. He wrote: “The … Barrow baskets submitted for consideration are modern and acculturated … Ethnology … has no use for such objects” (Krieger 1938). Nevertheless, art does not cease to be art because it is no longer traditional, any more than people stop being people because they are in the process of acculturation (Graburn 1967). The second goal of this study, therefore, was to contribute to the growing fund of knowledge about tourist art and to its legitimization.

Since baleen basketry had no corpus of existing literature, the information presented here is a mosaic pieced together from sources as scattered as they are fragmentary. Over the past two years I have made several research trips: two each to the Alaskan Arctic and the eastern seaboard, and four others around the rest of Alaska and the western United States. During these trips I have examined and photographed more than two hundred baskets in museums, private collections, and shops, and have interviewed basketmakers, scholars, collectors, ethnic art dealers, and others knowledgeable about the baskets. Throughout this same period, I have corresponded with those I was unable to see in person. My reconstruction of the history of baleen basketmaking draws heavily on these interviews.

Some facets of this study remain to be amplified by future research. Because I am discussing most aspects of baleen basketry for the first time here, a few important points are still obscure, others only partially illuminated. Some of these shortcomings are the result of insufficient evidence, others, perhaps, of inaccurate conclusions drawn in reconstituting history from so many disparate fragments. Future work will, I hope, close these gaps and correct any fallacies in the present investigation.

Fairbanks, 1983