Читать книгу Baleen Basketry of the North Alaskan Eskimo - Molly Lee - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

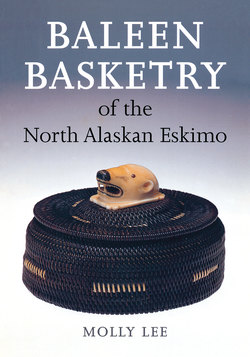

The seed of this study was sown on the June day in 1976 when I first saw a baleen basket. Browsing through the display cases at The Legacy Ltd. in Seattle, a mecca for lovers of Native art, my eye lit on a small black basket with an ivory carving of a seal on its top. The seal was posed as though sunning itself on the spring ice; tiny baleen plugs gave its eyes the right luster, and every whisker on its small snout was exquisitely articulated. Enchanted by the basket’s tightly woven, elliptical body, I turned it over and saw that a signature had been etched into the ivory starter disk on its bottom: Abe P. Simmonds, Barrow, Alaska, 1952. It was a name I would come to know well over the next few years. Despite the basket’s high price I bought it on the spot. As I walked out of the shop with it, I little realized that I had embarked on a six-year journey that would take me from Barrow, Alaska, to Nantucket, Massachusetts, and through the dusty shelves of libraries, archives, museums, and private collections in between.

This research was undertaken as part of a graduate program in art history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Frustrated by repeated attempts to find more information on baleen baskets than was available in one brief article (Burkher and Burkher 1954), I decided to research and write about them for my master’s thesis. At first the idea met with little enthusiasm from my committee. Baleen basketry was a tourist art, and only a year after the publication of Graburn’s groundbreaking study Ethnic and Tourist Arts (1976), tourist arts had not been accepted as a legitimate focus of scholarly research. Eventually, however, letters of support from several museum curators in Alaska won over the skeptics, whose enthusiasm thereafter was critical to the completion of the study.

My objectives for the thesis were threefold: to reconstruct a history of baleen basketry, to record its techniques, and to develop a taxonomy for the baskets. As literature on this topic was virtually nonexistent, I had to start from scratch. I interviewed basketmakers and other knowledgeable informants, gathered data from the baskets themselves, and searched archival and library holdings.

I began my research in the summer of 1980 with a month’s fieldwork in the arctic communities of Point Hope and Barrow, Alaska. How well I remember sitting in an empty teachers’ apartment in Point Hope, staring out at the Chukchi Sea, trying to summon the courage to knock on the first door. As is so often the case in rural Alaska, the children took care of that. Before I knew it I was being pulled by an army of small hands down the street to the house of Seymour Tuzroyluk, the Episcopal minister and master ivory carver. That month of fieldwork and several subsequent trips to the Arctic formed the basis of my description of technique and were an invaluable means of gaining information about the history of baleen basketmaking in these and surrounding villages.

Creating a baleen basket taxonomy, which depended upon finding a statistically viable corpus of baskets to measure, proved more difficult. I had assumed that I could obtain such a sample (a minimum of a hundred baskets) by canvassing approximately twenty museums in the United States with extensive arctic collections. Few baskets turned up from these sources, however, probably because of their “non-legitimate” standing. Most baleen baskets at that time were in the hands of private collectors, many of them retired Alaska teachers. Thus, my sample—more than two hundred baskets in all—had to be obtained in twos and threes instead of the tens and twenties I had hoped for.

In the spring of 1981 I made several trips around the United States, visiting old sourdoughs and measuring and photographing their baskets. A more hospitable—and patient—group of collaborators is difficult to imagine. I made many friends, and the memories of those times are with me still. Less entertaining but equally important for patching together the baskets’ histories was week upon week of archival research, mainly in Juneau, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. Even so, many questions still remain to be answered.

Data from the baskets were entered into SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science), one of the earliest statistical computer programs (and one that some maintain has never been surpassed). The program allowed me to quantify the observable differences among the various styles and types of basket. When these traits had been delineated, I worked with Catherine Mecklenburg, an editor and artist, who cast the descriptions in a scientific context and created the excellent drawings for the text.

In early 1983, after the thesis had been signed and filed, Kesler E. Woodward, then Curator of Exhibitions at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau, applied to the National Endowment of the Arts Folk Art Program for a grant to fund a baleen basket exhibition, publication of the thesis, baleen basket workshops in Barrow and Fairbanks, and a video about the art form. The proposal was funded and, with the participation of the North Slope Borough Commission on History, Language and Culture and the Atlantic Richfield Company, all components were carried out with the exception of the exhibit.

Twenty-one years after I walked into that Seattle shop, the Abe P. Simmonds basket has become an old friend. Today, the little ivory seal suns itself on the desk beside me as I write. In the interim, I have been surprised and pleased by the continued interest in this research. Once or twice a year museum curators, dealers, or collectors send me photographs of baskets to identify, and at least once a month someone asks for a copy of the monograph. I am happy, therefore, that the University of Washington Press has brought it back into print.