Читать книгу Creatures of Passage - Morowa Yejidé - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLAND’S END

Dash headed home from his first-time visit to his great-aunt’s apartment. It felt like he’d been there for days. He was energized now, proud of his excursion. He replayed the experience in his mind, remembering the strangers he approached in the hallways of the building, ignoring their startled looks when he asked where the “Car Lady” lived, as he heard people call her, for he didn’t know which floor or which door. And he was riveted by the possibility of his mother walking up behind him and catching him there.

A pungent odor had blown out into the hallway and seized him at once when his great-aunt opened the door. He’d been unprepared for her height. She was so tall up close, the tallest woman he’d ever seen, and when she glared down at him with that haunted look in her red-streaked eyes, he’d lost his boldness. She towered above, asking questions in that rocking, mesmerizing way she talked. He was amazed by the dark, cavern-like apartment, the floor filled with unknown things. And there was that curious piece of deep-blue cloth buried in the shoebox. She didn’t seem to like him touching it. But she was kinder than he thought she would be, and if there was so much candy readily available in a place like that, maybe the forbidden Nephthys Kinwell was not so bad. But most of all he thought about that half finger. He’d seen one like it before. On someone else.

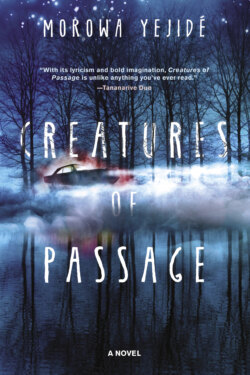

Dash walked on. As he hurried down the street, he saw the ill-famed Plymouth parked nearby, a hulk of steel that people whispered about. From the weird distances that places like Ana costia can create, he’d seen his great-aunt many times in that car. His mother forbade him to speak to or approach this blood relative without ever explaining why, and in his ten short years of life he’d never been able to understand the bitterness between his mother and Nephthys. Others in the neighborhood seemed to know something about what it was, but it was like they were privy to some lurid conversation that had been going on without him. And there was something about the way folks said those people when they talked about the Kinwells, something that didn’t seem good. But those people were his people, and something about that inescapable fact made him call the Car Lady he visited in the apartment “Auntie.” Was that all right? He didn’t know.

He walked on, hastening his stride through the spectrum of positives and negatives that places like Anacostia wrought: mothers handing treats to toddlers in strollers; policemen roping off alleyways with yellow tape; men waving to friends in passing cars; SWAT vehicles parked in front of buildings. He passed by the corner store he sometimes snuck out of the house to get to, thinking about the nurse’s letter and having to read it. Reading came easy to him (a teacher once talked of skipping him a grade). But reading the letter aloud made him feel like he was on display. Why couldn’t Nephthys read the letter on her own later? After all, it was addressed to her. And the lengths Nurse Higgins seemed to be taking to get to the bottom of his behavior troubled him. But you and I know that things can happen to a boy … What did that mean? Did the nurse know about what he saw on the day he opened that door at the end of the school corridor? He pushed the image of it away as he had so many times before, for it was still too big to fit into his mind.

He passed some men talking on a stoop. “What’s up, shorty?” one of them said. Dash nodded to him and walked on.

There were other things that lingered in his thoughts about the letter. Like when he read “man’s hand.” People murmured that phrase when his mother insisted that he stand close to her on the rare times they came out together to run errands. He heard the men in the barbershop mumble it when she dropped him off every few months and waited outside. And he heard it again after the fight with Roy, when the principal was pointing his finger in his face, saying his mother needed to have him dealt with. He had always wondered if a man’s hand somehow referred to his father, and this bothered him for reasons that he could not explain. He walked on, tired of trying to understand the things that people said. That was why it felt so good to shut Roy Johnson up, to bust his mouth for breathing a word about the River Man. And for talking about his mother.

* * *

Just before the fight broke out, Dash had been eating his lunch alone on one of the school benches when he heard his name.

“Dash Kinwell is crazy!” Roy Johnson announced. He was strutting around the schoolyard as if it were a stage. He’d skipped school earlier that week and hung out down by the river, and by chance he’d witnessed one of Dash’s exchanges. He was so flabbergasted by the sheer luck of his discovery that he waited three days to share the juicy news. “Dash Kinwell is crazy!”

The schoolyard quieted as the other children grew silent. The Kinwells were long the subject of witchcraft and legend, and when they heard the Kinwell name they gathered as if warming themselves around a campfire.

Roy’s eyes lit up with the thrill of the spotlight. A scrawny boy with a big mouth inherited from his gossip-mongering mother, his small stature would have made him an easy target. But he was the principal’s nephew, and he took every opportunity to remind others of this fact. He relished pulling the ponytails of girls and throwing dirt on their dresses, sassing the teachers, and stealing coins from his classmates and then claiming that they were just jealous of his riches.

Roy waited for the other children to fully assemble and join him in the jeering. “That’s right. I caught him talking to himself at the river. Talking to the air!”

A hush came over the children, for that meant Dash was off.

“Oooh …” a little girl named Lulu said. “You crazy, boy.”

“And they gonna be bringing Dash up to St. Elizabeths soon,” said Roy. “Because I saw him steady talking and steady nodding and wasn’t nobody there.” He looked over the heads of the children at Dash on the bench, laughing and pointing. “Hey, Dash! Tell ’em! Tell ’em! Yeah, you was just talking and wasn’t nobody there. Jabbering and saying something to somebody. What you call him? The River Man, right? And who’s the River Man? Nobody. Because Dash Kinwell is as crazy as his witch mama!”

The children gasped at the revelation that confirmed the things they heard their parents say. How Amber Kinwell’s coiled hair turned to snakes with deadly venom when she got angry. How she had cephalopod ink coursing through her veins instead of blood. How her garden grew by the power of black magic. How she put roots on people she didn’t like and “worked the moon” on anyone who looked her in the eye.

Dash was listening as he sat on the bench, his face growing hot. There were many things about his life that he’d learned to tolerate, but someone calling his mother crazy was not one of them. He stood up from the bench and headed toward Roy.

“Crazy as your mama! Crazy as your mama!” Roy was jeering. He was about to back down when he saw the look on Dash’s face, but then he remembered that he was still the principal’s nephew. And he knew—as all children of Anacostia do—that to show fear was to show weakness. He looked at the children watching, electrified by the bloodlust he saw in their eyes, and continued: “Yeah, that’s why your mama got that head of snakes and your drunk-ass auntie drives that ghost car.”

“Take that back,” Dash hissed.

“And now you talkin’ to yourself.”

“Shut up!”

“The evil black Kinwells. Everybody knows all about that witch at the bottom of the hill and that drinking, demon-car-driving—”

“I said shut up, you little rat!”

“And a jive turkey who talks to himself by the river when ain’t … nobody … there. I ain’t see a soul but—”

That was as far as Roy Johnson got. Because by then Dash had picked up a rock and tackled him to the ground and was pummeling his face.

* * *

Dash continued his walk home from Nephthys Kinwell’s lair, avoiding deep cracks in the sidewalk and the glass from broken bottles. He stepped over an exposed water main pipe jutting through the concrete. He heard the distant chimes of an ice cream truck, which told him that school had let out. Children seemed to come out of nowhere at the sound. A group of preschoolers appeared on someone’s porch, and together they began a happy chant. Some dropped their toys and ran inside to ask for money.

An ambulance siren screamed by and Dash sped his stride. He was about to cross the street when he saw Lulu, one of the girls who’d joined Roy Johnson in taunting him earlier.

“You crazy, boy!” she shouted from across the street.

Dash walked on, ignoring her.

“Hey, crazy boy! Crazy as hell like that witch bitch.”

Dash heard that word again. Crazy. And now the word bitch, referring to his mother. Boys weren’t supposed to hit girls, he’d been told. But he thought about slapping Lulu into the sidewalk if she kept on.

“Crazy boy! Crazy boy!” the girl chanted. She had learned very early from her big sister Rosetta that there were two kinds of people in Anacostia: hunter and prey. You be the hunter, not the prey, she’d told Lulu before she ran away across the bridge. But later on, when Lulu saw her prowling the streets or getting in and out of cars, she caught a glimpse of some frightened thing that seemed to have crept into her big sister’s eyes, so that she wondered if the hunter and the prey took turns being the other. “Witch bitch!” she shouted now with more fervor, until she crossed a woman sitting on her porch.

“What you say?” snarled the woman.

“Huh? Nothing.”

“What you say?” asked the woman again, louder. “Ain’t you Rosetta’s little sister? I know your mama, girl. And I’ma tell her about your damn filthy mouth.”

Lulu smirked, but she felt a chill inside. She wanted to tell the woman to kiss her ass, but she was not sure if what she’d said was true (about telling her mother). That could mean a whipping. She glared at Dash once more. “And plus … plus … your daddy was that crazy niggah from the war who used to be in your mama’s garden! My mother said so!” She stuck out her tongue and ran back the other way.

Dash watched Lulu run off. What was she talking about? She didn’t know his father. No one knew his father. But there were times when he looked at the picture of the blond-haired family in the unit chapters of his schoolbook (mother, father, little girl, little boy, golden retriever) and wondered who his father could be. He could think of him only as an idea or concept. Or a shadow coming down the hill. But his mother never spoke of him, not even his name. And no one ever asked how it was that Dash Kinwell came to be, since children born of Anacostia appeared and disappeared from one day to the next.

He walked on, passing an abandoned lot filled with weeds like tall wheat. He crossed the street and went by a row of boarded-up houses, the yards overgrown with an explosion of dandelions. Now he came to the hill that led to home and it was time to forget all he heard and saw on the street and empty his mind. He couldn’t worry about Roy Johnson or Nurse Higgins’s letter or Lulu’s wild talk. Because now he would need all his strength for his mother.

* * *

Dash arrived at the edge of the world, the brink of a steep hill that dropped to a small valley where a lonely house stood dwarfed in a vast tract of mud, which from that distance looked like a slow, heaving river. The blanket of clouds that hung always with varying thickness over the little valley coated everything below in cerulean, so that the long-faded and chipped paint on the house appeared all the bluer. He knew that his mother was somewhere under that roof and gathered his strength.

Because she hardly left home unless pressed by the greatest of need. When she did, she was met with odd reactions that Dash had only noticed as he got older. Shopkeepers and vendors refused to conduct any business while standing directly in front of her. They collected money for their wares from a special basket kept on the edge of the counter for her payments. All things were sold to her at discount and always in ample supply, lest she need to make a special order or request that required them to look her in the eye. Every bus ride was free. What was harvested from her garden was bought at the price she asked, without inspection or negotiation, the money placed neatly in an envelope and left for her retrieval. There was the old Polish postmaster who answered yes to anything she said to him when she came in once a month to handle the mail. A telephone had never been installed at the Kinwell house. No one from the electric company ever came down for service calls or to disconnect the power line. And even in the blackouts of midnight thunderstorms, the single bulb hanging from the porch roof burned like the North Star.

Dash sighed, preparing for his descent. Because it would all start again when he reached the bottom and went in—his mother acting like something was going to happen to him. And he knew it had something to do with the dream about him, this dream that breathed always on their necks and gripped them both in the quiet of the rooms. He could tell by the way she looked at him now. It was the same way she looked at the people she talked about in the Lottery. And sometimes when he was hostage to her mania (heavy sleeping, insomnia, questions, silence), he wondered, reluctantly, if the things people said about his mother were true.

He trekked down, landing in the mud at the bottom. There was a garden on the side of the house, and in the microclimate of the valley, the soil was as rich as it had been since the Paleozoic era. The garden exploded with the most feral of produce many times larger than the normal size. Massive collard and kale leaves spread in Jurassic splendor. Mammoth carrots and turnips shot from the ground. Huge tomatoes and watermelons proliferated in a burst of shapes like a colony of boulders. In the rear was a gigantic stand of cornstalks that rose to the second floor of the house, and fat yellow cobs yielded early, so heavy that they dropped to the ground like apples from a tree.

Dash walked by the jungle of vegetation and reached the wood-planked porch, slippery with sediment like the teak of an old ship, and it bobbed and buckled as if it had been long overtaken by flood. The rotting shingles around the single windowpane saluted him with the usual dreariness. And as the air drained from his lungs, his body tightened and compressed with each step closer to the door. He looked up to the top of the hill once more, a kind of last-rites habit. The edge where he’d stood just minutes before was now obscured by the cloud coverlet. He took one last deep breath and turned back to face the entrance.

Dash looked into the translucent glass of the doorframe. The realm behind it waited. He put his hand on the doorknob, cold and slick with moisture, and pushed the door open with a whoosh. He stepped in. There was the oppressive density of the interior, which rushed over him immediately; a colorless odorless tasteless substance that filled the house for as long as he could remember, something that seemed thicker and more difficult to breathe than air. He stood in the drift and listened. Nothing. But he knew his mother must be somewhere in the depths. He looked around and cocked his ear. “Mama?” He ran his hand along the dew-coated wall, walking from room to room. What filled the house muffled his steps so that his movement was nearly soundless. He listened again. Nothing. “Ma?”

“You’re back,” said a sudden voice.

The acoustics of the house let Dash know that his mother’s voice came from somewhere in the kitchen and he headed there. “Yes, Mama,” he called out. “I’m home.”

When he entered the kitchen, he saw a large cast-iron pot on the stove with bluish steam rising from beneath its heavy lid. On the table there were three enormous carrots that stretched across its top entirely, and a green pepper the size of a pumpkin squash. His mother was at the sink pulling the bones from a tray of rockfish with a pair of pliers. His heart skipped. Fish meant that she had gone shopping at the market—today of all days—and his stomach dropped. Did she see him creeping around town before school was out? Trying to stay calm, he reminded himself that he’d made it back in time to dodge suspicion. The visit to his great-aunt’s apartment didn’t delay him long enough to appear as if he was coming from anyplace else. His mother didn’t know about the letter from Nurse Higgins. And she didn’t sound upset with him.

Amber turned around and looked at him. Her eyes glistened with warmth but she did not smile. “Heard you come in.”

Dash made a stoic face. The window above the sink filtered in light that accented his mother’s long, coiled black hair, which clung to her thin frame like thick ropes of seaweed about some sunken statue. The birthmark between her eyes was obscured and only her full lips and chin were visible in the marine shadows. Even without a smile, Dash thought that she was beautiful, some enchanted waterborne species. He nodded. “I’m back.”

“Thought I’d make some fried fish for dinner. I know it’s your favorite.”

“Sounds good. Do you want me to wash off the carrots?”

“After a while. Better start your homework, if you got any.”

“No homework today.”

“Really? Then come sit and help pick out the bones.” She brought a tray of cleaned fish over to the table.

Dash pulled out a chair and sat down.

Amber handed him a slippery rockfish that was already halved. Dash held it in the light and looked at the skeleton sunk into the flesh. The splayed fish, with its delicate vertebrae, not yet seasoned and crispy with cornmeal, reminded him that it had once been a living thing. Now, like everything else in the house, it had been taken over and would be turned into something else.

“Just pull out the big bones,” his mother was saying. “I’ll come behind you and get the little ones.”

Dash got into the rhythm of pulling away fins and skin and bone from the fish and dropping the flesh into the tray. But he knew the solace would soon end. Because he could feel the doom forming again, the enigma at the heart of everything between them: the dream. He braced for the ritual to begin, one of many.

“How was school?”

Dash didn’t look up. “Ma’am?”

“I said was school okay today?”

“Yes.”

“Was the walk all right? You came straight home, right?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Nothing different?”

Dash dropped a piece of fish on the tray with the expressionless face that years of having Amber Kinwell for a mother had wrought. There would be more questions if he didn’t keep his answers short. Nothing in his response could be out of place, the unmentionables kept hidden. The suspension and the letter. The mystical danger of Nephthys Kinwell’s chamber. But more than that, as hard as it was to quarantine it at the edges of his mind, he had to shroud what he saw (imagined?) at the end of the school corridor. Behind that door in that other dimension. But if he’d imagined that, then he feared that he was also imagining the River Man, and he was not prepared for what that could mean or not mean. “Nothing, Mama.”