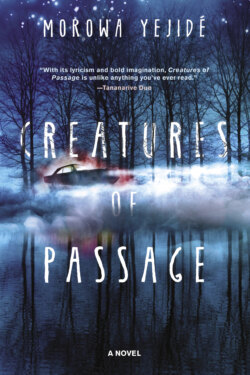

Читать книгу Creatures of Passage - Morowa Yejidé - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSORCERY

At the site of the hit-and-run accident that left a pregnant woman in a pool of blood on a street in Anacostia, an infant splashed inside her mother’s cooling fluids. As the woman moved from one plane of existence to another, the preborn lay quiet in her amniotic water, listening to the sound of her progenitor’s heartbeat slowing to a stop. And in accordance with the law of reciprocity, where nothing is taken without something granted, Death whispered the star recordings of lives into the infant’s ear, gifting her with the vision of another life’s end. With each tale of reckoning the infant’s eyes widened anew, unblinking in the darkness of the womb. And when finished whispering the register of fates, Death touched the neonate’s forehead lightly with its finger, leaving a mark.

* * *

Amber stood at the kitchen sink, staring through the window at a small stand of old trees. She was doing this more and more, and each time she felt like someone was staring back at her, waiting. But everything was as it had been the day before, with the lily patches and tree gnarls and knobs unchanged. The places where lightning had written its name on the bark remained. There was no one there.

Puzzled, she turned away from the window and finished washing the breakfast dishes. Now that Dash was off to school, the house was quiet, save for the creaking of its hull. She stood listening to the silence, feeling listless. Unlike so many other days, she didn’t want to idle away her time washing and cutting the spoils of the feral garden. She was not in the mood to fill the long hours with endless tasks: shaking out the sediment-covered blankets; wiping condensation from glass; scraping the verdigris from the kitchen chairs; gouging mud from the hallway floor planks; collecting salt from corners.

She poured herself a glass of water and sat down at the table, watching particles float by in the cool, interminable current like phytoplankton. But even in that calm, flashes of the dream about Dash took hold and she began to fret once more, for the dream seeped into everything. She stood up from the table and paced the floor. She thought about going up the hill but couldn’t decide why. Was it to look for the unknown man in the dream? But how? It all played in her mind. A forest. A dead cardinal falling through the trees. A faceless man, lurking, then chasing. Then Dash running through the trees. She could see him lying in a creek.

Her blood ran cold at the last image. It maddened her that she couldn’t see more. Just flashes. The only thing that was clear was doom. Nothing like that first dream when she was a girl. Nothing like the shark. Her mind raced. Who was the faceless man and why was he chasing Dash? Maybe she should be walking him to school and back from now on? Or just keep him at home? Then she would sleep better and watch him more. I could keep him in the house …

A knock at the door startled her and she jumped. But then she remembered that it was the second Monday of the month. That meant it was time for the Lottery, the last thing she wanted to think about now.

There was another knock.

Sighing, she made her way to the front door and opened it.

Mr. Johnson was standing on the porch, stomping and scraping his feet, a feeble attempt to remove the thick mud from his shoes. He held the elegant air of a jazzman in his sand-colored suit and brim hat. He ran the storied Afro Man, a local independent newspaper that featured stories about the state of black people in the territories. On the second Monday of each month, Mr. Johnson came to the bottom of the hill to personally speak with Amber Kinwell. A tenacious businessman and one of the few people who ever dared visit, he understood the dollar value of Amber’s dark gift to the sales of his newspaper. He’d been listening to the stories about her for years. The sea breeze that preceded her wherever she walked. How her wild black hair held a supernatural tint, and how her shoulder blades were dusted with salt crystals. The warnings never to look her in the eyes, the only protection against her glare of ruination. People said that the birthmark on her forehead was the thumbprint of the Devil. He heard these things and more and didn’t believe most of it. But he was never sure about her eyes.

Mr. Johnson smiled without looking up. “Good morning, Ms. Kinwell.”

“Morning,” Amber said, holding the door open.

“Thank you. I’m glad we meet again.” The newsman’s eyes traveled up slowly, stopping at the wonderland of her hair.

Amber nodded. She knew that he made a point never to look at her directly like everyone else, but she liked his warmth and ordinariness. And he didn’t seem to fear her.

Mr. Johnson took off his hat and stepped over the threshold into the foyer. Once inside, the lighter palettes of the outside world just steps away melted into deeper hues. No matter how many times he’d been to the house, he was never prepared for that darkening. Gradually, his eyes adjusted as he stood in the vestibule, and he felt his heart slow in the thickness of what he now had to breathe. “Appreciate you having me over.”

“Can I offer you some coffee?”

“Awfully kind, but no thank you.” He followed her down the hallway. “Drank a whole pot last night and haven’t been to sleep yet. Had a problem with a story and almost missed our deadline. Nearly knocked me down. But we got it straightened out.” He let out a nervous chuckle as he followed her into the kitchen.

“Please have a seat,” said Amber. “Water?” She took a pitcher from the pantry.

In the heaviness of the house, water was the last thing the newsman wanted. “Sure, I’ll have some.” He looked into the pantry. The shelves were crowded with rows of mason jars filled with the bounty of the garden, he supposed. But in that beryl light, the contents looked like huge globules in lava lamps. And although he’d been to Amber’s amphibious lair before, the spectacle of her astonished him every time. The floating vines of her hair like ropes of seaweed. The black sheen of her orca-like skin and her thin, chiseled limbs. He stole looks from the corners of his eyes and watched her pour water into a glass, fascinated.

Because the truth was that the newsman believed in Amber’s ability and power, for he hailed from the mystic bayous of the Kingdom of Louisiana. He was raised by a grandmother whom even the rulers of that land consulted before making any serious decisions. His grandmother was a magic woman, a seer who spoke of what she called the Great Loop, and he thought about the things she said each time he was in Amber’s presence. She talked of how damnation was the inescapable circle one made around oneself. How payment would come due for the plunder and ravage of the earth, for there would be superstorms to drown millions and pathogens crawling from one place to the next. She spoke of the cycle of happenings in the empires of the world, with each century marked by the same gall of deed and outrage of talk. But more than anything, he remembered his grandmother saying: “We just going round and round, we creatures of passage. And we gonna keep going round till we understand the Loop.” And sometimes when he looked at the glint of Amber’s dark skin, he thought of his grandmother’s tale about the black wolf whose coat was slick with the elemental oils of the spaces through which he passed, and how the wolf knew the start and end of all stories. So it was no surprise that the newsman was inclined to take Amber and the Lottery seriously, since from his grandmother he’d inherited the tremendous strength to record the happenings of the ages and then watch them repeated.

“Make yourself comfortable,” said Amber.

“Don’t mind if I do. Hope you’ve been well.”

Amber rubbed her eyes. She hadn’t slept much again. “Well enough.”

Mr. Johnson looked at the flower print on Amber’s dress. He’d been visiting her each month for a long time, except for that brief period years ago, when she asked him to stop. He’d heard gossip that it was because she had a man around then, but he could never confirm who it was. And then he’d heard she had a baby, so that must have been the son’s father. What happened to him? He didn’t know. The newsman smiled and looked into the tendrils of Amber’s hair. “Appreciate your time today, Ms. Kinwell. Can’t believe it’s June already. The year has just been flying by. How’s your boy?”

Amber filled her own glass with water and didn’t respond.

Mr. Johnson cleared his throat in the awkwardness of the moment. “I thought we might discuss the Lottery in the usual manner today. As you know, folks take an interest, and I never was one to dismiss the powers of the spirit world.”

Amber looked beyond him to the window over the sink that framed the trees. She felt that strange sensation again, as mysterious to her as the origins of her ability. She gazed back at the newsman from across the kitchen table. “You know, my mother died before I was born.”

Mr. Johnson was looking at the angles of Amber’s collarbone, prepared for anything she wanted to discuss, but he was yet unsettled by her sudden statement. He scratched his head. “Childbirth?”

“They say it was a hit and run.”

“Goodness gracious. They ever catch who did it?”

Amber shrugged.

“Mighty heavy load, not knowing.” He was curious about something else now. Because although he’d heard of the tragedy of how Osiris Kinwell was later found, he’d always wanted to know more about his twin he saw driving around sometimes; if what people said she did with that Plymouth was true. And why she and Amber seemed to have nothing to do with each other. He shifted in his chair and began carefully. “Some terrible things have befallen your family and I’m so sorry. Must have been hard on your aunt too.”

The house creaked and a wave of silence rolled into the room.

The newsman looked at the glass of water in front of him and suddenly it was all he wanted. He drank it down in one long gulp and the heaviness in his chest eased.

“Yes,” Amber said. “My aunt Nephthys.” And here she waved a hand as if the gesture would clear the subject away. Because talking about Nephthys meant she had to think about the very first dream she’d ever had. She had to think about her father, the river, and the shark. “Let’s get the Lottery done now.”

Mr. Johnson didn’t press the matter further. He took out an envelope containing her payment from his jacket pocket and placed it gingerly on the table. Then he took out a pen and a small pad. “I’m ready when you are. Say the word.”

Amber leaned back in her chair. As always, a kind of nausea washed over her like seasickness. She didn’t have to conjure the flashes of her dreams, since they came to her of their own accord. But each dream had different details. And now she was too exhausted to say anything but the basic elements, since the one dream worrying her took up most of the space in her mind. She tilted her head and began:

1. Police raid. Green house with the big philodendron on the porch. Body in the closet.

2. Pink pacifier and bottle. Box buried in the yard. Frederick Douglass house. Study cottage in the back.

3. Red, white, and blue beads on the ends of braided hair. Train tracks. Washington Bullets T-shirt. Kingman Lake.

4. Wires on fire. Apartment on Dotson Street. No numbers on the doors. Windows nailed shut. Woman can’t breathe.

5. A mother. Five children. A man named Wilson holds his arm and loses his heart.

Amber stopped and twirled a lock of hair around her finger and let out a long sigh.

Mr. Johnson was writing furiously on his notepad, recording every word she said, and he put his pen down when she stopped. As always, her death dreams were ghastly, more so because he knew they came true. Young women killing themselves when they’d fallen on hard times. Houses burning down with families in them. Shootings and stabbings and poisonings. Boys hung in jail cells and that sort of thing. Despite the fortitude inherited from his grandmother, the death dreams bothered him long after he wrote them down and had them printed. He had stopped confirming the gory details of Amber’s foretelling in the television reports and obituaries, for this interfered with his ability to sleep at night. He stared into the green lines of the table. “Is that all?”

The floorboards of the house creaked as if buckling from some unseen pressure.

There’s more, Amber thought, staring at her guest’s empty glass. There was so much more in the five visions than what she’d described. And there was the dream about Dash. But speaking of that meant acknowledging what she couldn’t bear to accept. “Yes, that’s all of it.”

* * *

Amber stood topside on the wood-warped porch like the deck of a ship, watching Mr. Johnson drift into the mist until he was out of sight. Her legs grew tired and she sat on the step, weary from the doldrums of precognition. Once more she thought about that first death dream when she was twelve, a bizarre and horrible vision about her father. And once more she tried to understand the reason why she’d seen him eaten by a talking shark but was unable to do so. It’s just a dream, she’d told herself back then.

And she’d believed it for a while too, until her father’s body was found. When Nephthys came back from the morgue with the news, Amber ran around the garden, screaming. Later on, she told her aunt the dream she’d had about the shark. She remembered Nephthys telling her that it didn’t mean anything and should be forgotten. “Real be worse than any dream,” she’d said. But from that moment on, there was something about the way Nephthys looked at her: an accusatory gaze, a silent rebuke. The dreams were more frequent after that, and they got worse as she grew older. Different people with different deaths. More chilling in clarity, more terrifying in accuracy.

Amber stared into the thickening cloudcap. Neither she nor Nephthys had ever found out the particulars of her father’s undoing from the autopsy or the police; how he ended up in the river or who put him there. But the facts of the chewed-off leg and ravaged body followed them wherever they went, floating about the rooms of the house, festering and poisoning everything between the two of them, until her father’s death drowned them both.

Amber got up and went back to the kitchen and cleared the table. At the sink she looked into the small stand of trees. Again, they seemed to stare back at her, full of the enigma that places like Anacostia create. And once more she asked the silent wood what she’d asked a thousand times before: What happened?