Читать книгу Betting on a Darkie - Mteto Nyati - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеJohannesburg 1986

Circumstances are beyond human control, but our conduct is within our power. – Benjamin Disraeli

My previous experience of the City of Gold had been as a cosseted sixteen-year-old science olympiad student. As an adult, I found it somewhat daunting and I became aware, more than ever, of the many sides to South Africa. Afrox head office, where I was to undergo a training period, was in Selby, near the city centre. Blacks weren’t allowed to live there so I had to find a place in Soweto, which was the closest township – about an hour’s ride away on public transport. I’d never stayed in a densely populated area before, let alone in one that was a hotbed of political activity. A protest campaign, which took on various forms, was gaining momentum across the country: in Soweto there were rent boycotts, mass stayaways and a spirit of defiance that even a constant military and police presence couldn’t dampen. In the city and surrounds there were occasional bomb blasts at railway stations, police stations, hotels and shopping centres.

I put my head down and concentrated on my new job. Afrox had invested in me, paying my fees from the second semester of my first year for the duration of my four-year degree. A condition of my scholarship was that during my university holidays I had to work at Afrox air-separation plants. My first job had been at a gas plant at Maydon Wharf in Durban, where I was issued with company overalls, gloves and boots and assigned to a boilermaker, who taught me how to weld. If my father had seen me – as a boilermaker’s gopher – his preconceived ideas about engineers would’ve been justified. Later, through guided experiments, I learned to research methods to improve oxygen yields from air. Gases such as oxygen, nitrogen, helium and argon are present in the air. Through cooling them past their boiling point, they are separated into components, transforming them into liquid oxygen and nitrogen – required for Afrox’s production needs. It was my first stab at chemical engineering.

The only person I knew at Afrox HQ was the labour relations manager, Lot Ndlovu, who had recruited me. He was an industrial relations expert whose ability to sidestep unions in favour of workplace forums made him useful to Afrox. Under him, grievances never made it beyond the factory floor. Cosatu had been launched in 1985 and its programme of ‘rolling mass action’ unnerved many in white-run industries. In the ’90s Lot would become president of the Black Management Forum (BMF), CEO of People’s Bank and a proponent of the reversal of inequality through realistic negotiated targets – Black Economic Empowerment.

But in the ’80s, black corporate professionals were limited to a few experiments like me. It was tough. Lot’s only advice to me was ‘don’t mess up’.

With his help I found a place to stay in Diepkloof – an electrified, fairly modern two-bedroomed house I shared with a guy from Limpopo. My housemate John and I took turns to do the cooking; he produced pap and I made umngqusho onembotyi (samp and beans). The rent was R200 a month, my salary R2 500, so I had enough left over to send money home. My three siblings still had to get through university; my mother wasn’t as strong as she used to be and business-wise there was competition in Tabase as other trading stores had opened up.

There was a bus stop a few kilometres from my new Soweto home and I caught a Putco bus to work every morning. I wasn’t exactly the epitome of sartorial elegance. I didn’t own a suit and wore the same jacket and tie every day, with mismatched trousers and shirts.

Afrox abided by the Sullivan principles, developed by African American preacher, Reverend Leon Sullivan. He’d been on the board of General Motors in the US during the ’70s and had used his corporate foothold to act against apartheid. General Motors was the biggest employer of black workers in South Africa at the time and, through pressure from Sullivan, had adopted a code of conduct that promoted corporate social responsibility and non-discrimination in the workplace. It encouraged other companies to do the same. So when I got to work at Afrox, segregation was temporarily suspended and I could use the bathroom, canteen and other facilities alongside white colleagues.

But I was still the elephant in the office. I was the only black engineer and the first black person ever to have been awarded a bursary. Apart from Lot Ndlovu, who was on another level, the only other black employees were cleaning and support staff. Not only did I have to make sure I didn’t ‘mess up’, I would have to be the elephant that danced.

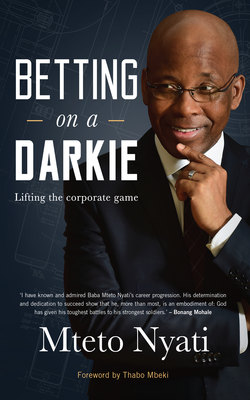

I became conscious that I – along with fellow bursary student Ruth Stenhouse, a Wits Chemical Engineering graduate – was an experiment. Afrox’s internal newsletter, Inform, featured Ruth and me smiling broadly with our mentor, Dave Bawden, the operation engineer gases:

As Afrox prepares for the future so its manning patterns, as with its technology, must mirror a changing world. The selection of Ruth Stenhouse and Mteto Nyati as Afrox bursars and then engineers-in-training gives an indication of the staff who will provide our technical expertise and leadership in the years ahead.

Both these young graduates are members of minority groups: Ruth was one of three woman graduates in her class, Mteto, the only black graduate in his.

When questioned about being the first woman engineer at Afrox, Ruth, in her practical and forthright way, said she believed it was an advantage. ‘People are not likely to forget you,’ she said.

Mteto came to engineering along a traditional route; the mechanical fascination of repairing old cars told him where his interests and aptitudes lay.

Ruth and I, the rookies, were sent off to Afrox plants in Germiston and in Brits, the domain of the white male. I was pleased to have her with me. The looks we got and our exclusion from certain conversations made us acutely aware that we had to shatter stereotypes. I knew there was only one way to do this: by making myself useful.

My chance came when I was tasked with production planning at plants by monitoring customer demands. At the time, there was no system in place to accurately work out storage capacity and daily production, and no one seemed to even know if we should be generating more or less. I wasn’t entirely sure how they expected me to work this out without data, and fleetingly wondered if they were just trying to keep me busy – or set me up for failure.

I didn’t know where to start. Nothing in my degree had trained me for this, except for a brief introduction to computers in my fourth year, which I hadn’t imagined would ever be of relevance to a career in engineering. I was familiar with a program called Fortran, a system developed by IBM in the ’50s, which had evolved into an effective tool for numeric and scientific computing. Through working with it, I’d learned a set of computer instructions that could be used in different combinations to get the computer to produce specific outputs. Once I’d got the hang of it I was surprised how it helped me to think logically in life, but Fortran was far removed from the dBase III program I now had to get to grips with. dBase III had a completely different set of instructions: it was like learning a new language. There was no one who seemed willing or able to help me, so I started training myself.

I was given a laptop, a clunky white machine with a small screen in a clamshell-type cover, and began visiting plants to collect data. I gradually got caught up in programming, working out daily production, overtime needs and how to reduce costs. Within a year I had developed a ‘prod-planning’ monitoring module that matched required levels of production to resources, and estimated future demands.

I also helped put in place a system to make the delivery of our product more efficient. In those pre-GPS days, our drivers would be given their daily orders and disappear with their gas-laden tanks. Routes and distances weren’t worked out or monitored, and drivers did their own thing, without accounting for their time or reporting what percentage of their schedules was taken up by deviations and breakdowns. I began accompanying them on their routes, calculating distances between deliveries. I spoke to sales agents, found out their needs, took into account customer complaints and came up with a computer program that streamlined the delivery process. It didn’t sit too well with drivers who could no longer skive off once their deliveries were done, but it gave management a far better understanding of the company’s operations.

Although I kept myself busy, I still couldn’t shake off the feeling that I didn’t fit, that I was being avoided instead of embraced. Once I’d finished a project, my next wasn’t always waiting for me, despite the fact that Afrox was forging ahead, investing in healthcare and supplying oxygen to hospital groups, and trying to stay ahead of competitors such as Air Liquide and Air Products.

One of the managers, Neil Greenfield, had been sent overseas to find out about trends in Japan, which was in the midst of a three-decade-long economic miracle and way ahead of the pack in the field of technology. He reported back that the new world focus was on training and retraining employees in how to communicate with customers, to exceed customer expectations and how to use IT to improve customer satisfaction.

Neil was given funding to start a quality management unit. He selected me to be part of his four-man team. Under his guidance we were to develop an advanced troubleshooting system that would ensure products and services were consistent and, if there was a problem, to be able to trace the source. In this way, customer needs were anticipated, complaints circumvented and management decisions based on evidence. One of our inventions, which I’m pleased to say is still around today, is the simple plastic seal on the neck of a gas bottle that traces its origins and production history.

I started realising the importance of teamwork and communication and finally felt as if I fitted in, that I wasn’t a special case, an anomaly that needed to be kept busy. Neil, I rightly assumed, had chosen me because I had the necessary training to do what was expected of me. He became my mentor and under him I began approaching my job in a more methodical and professional way. He was about five years older than me and I admired that he seemed to have his life mapped out, planning to retire at 50 and travel the world, seeking places and adventures that challenged him.

Years later, when he was living in Germany and I was MD of Microsoft South Africa, we met up in Joburg. He had done as he’d said he would: given up formal work to explore the exotic and the unusual.

I thanked him for embracing diversity and for taking a bet on me.

Words from Ruth Stenhouse Smith

One of my abiding memories of my work at Afrox in the 1980s is of us trainees in our overalls in the middle of a cold Highveld winter, getting workshop experience with the artisans at the Germiston plant. I used to think: did I really spend four years at university to dress like this and learn how to use a lathe? At first they taught us to use the workshop equipment and finally do a trade test, which meant following technical instructions and setting up the machines correctly, then it got more rigorous: working shifts and preparing for a shutdown. I remember being on duty from the Thursday before Good Friday and all the way through the Easter weekend – with minimal sleep.

I wasn’t too intimidated by the all-white macho male atmosphere. My father was an artisan so I guess I was used to it, although working at the Germiston plant had its moments. The maintenance superintendent had wall-to-wall Scope centrefolds pinned up in his office! Mteto and I were definitely an anomaly: the regular staff weren’t used to female or black trainees. I remember being sent to a steel foundry in Vereeniging and they wouldn’t let us in, not believing that we were actually engineers. Mteto was always quiet and unchallenging, despite the patronising atmosphere at times. I was the only female to finish in my class at Wits and he the only black graduate in his at Natal, so we knew we’d be entering an environment where we stood out.

At our headquarters, just off the M2 in Selby, we had an office on the first floor and were under the wing of Dave Bawden. He was an operations engineer, but also mentored the new recruits. His main concern was that we keep our desks tidy! Cluttered desk, cluttered mind and all that …

Afrox human resources (HR) was fantastic – they would throw you in the deep end and then support you with training and good advice. There were lots of industrial strikes in the ’80s so we had to do our heavy-duty driver’s licence – Code 14 – and at one stage I drove oxygen trucks to hospitals at six in the morning. Talk about varied training.

Afrox HR set the tone for all my other jobs. I went from gas to drugs to alcohol! After Afrox I got a job with Adcock Ingram as logistics manager, then at SA Breweries as a project consultant, until they were taken over by AB InBev.

These days I design beer breweries all over the world – Tanzania, Romania, Canada – from my little office in Sandton. A few years ago I attended a project management course and the course leader, Amanda Ellis, had worked at Microsoft with Mteto and raved about his leadership and quoted him a lot. It took me back 30 years to that quiet trainee engineer who observed much and said little.

– Ruth Stenhouse Smith is senior design manager at Blue Projects Company