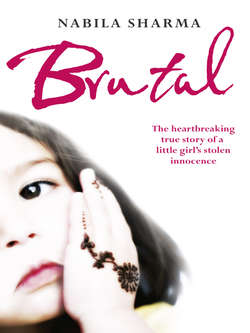

Читать книгу Brutal: The Heartbreaking True Story of a Little Girl’s Stolen Innocence - Nabila Sharma - Страница 6

Chapter 2 Living on Sikh Street

ОглавлениеOur end-of-terrace house, a little red brick building on a corner, looked identical to the others in the street apart from the corner wall, which was crumbling in places, giving the neighbours a full view of our messy back garden.

Dad was always trying to lay paths or fix things up in the garden, but I liked the fact that there was no solid wall because it gave me direct access to the house of my friend Suki, who lived on the other side of the road.

From the outside our house may have been the same as the rest in the street but the family inside was different. We were Muslims living peacefully alongside our neighbours and friends, all of whom happened to be Sikhs. I wouldn’t have even considered the difference if my older brother Habib hadn’t pointed it out to me.

‘Muslims and Sikhs hate each other,’ he insisted one afternoon.

‘Why?’ I asked. Suki was a Sikh and we didn’t hate one another. She and her family were lovely.

‘It’s tradition. It’s to do with land,’ Habib said, not really explaining. ‘It’s how it’s always been.’

I shook my head. It didn’t make any sense to me. ‘Well, I think it’s silly.’

But Habib wasn’t listening. He’d already turned away. I didn’t understand what he had against Sikhs. I liked to call our road Sikh Street because I went to school with Sikhs, our neighbours were Sikhs and my best friend was a Sikh. It didn’t matter that we were Muslims. All I cared about was which dolls Suki and I would play with later that day.

Unlike our house, Suki’s was a newly built four-bedroom detached house with its own garage. The garage door was white, just like the walls inside the house. Compared with the hustle and bustle and general chaos of my own home, Suki’s felt like heaven. It was clean and clear inside, with hardly any furniture. I was used to a cluttered house full of storage boxes from the shop, but Suki’s had what seemed to me like acres of space.

There was a garage built on the side of the house but the family didn’t keep a car in there. Instead, they’d turned it into a special prayer room, which you reached through a door just off the kitchen. Suki’s mother had covered the entire floor of the prayer room with white sheets. We’d sneak in there and I’d gaze at the musical instruments that rested at the bottom of the room by the window. There was only one window that overlooked the back garden, so it was nice and private. A huge picture hung on a wall. Suki said it was their God, but that didn’t bother me, even though I was a Muslim. Suki’s family were deeply religious but they were also very kind. They didn’t worry about me being Muslim. It didn’t seem to matter to them.

All of Suki’s family played the instruments in the prayer room. Suki was learning the tabla, which was a small drum. My eyes lit up whenever it was time for her to practise. Her mum noticed and decided to teach me too. The whole family allowed me to bang the drums and pluck at the strings of the sitar, even though I couldn’t do it properly and just made a din. I always loved being in their prayer room.

Unlike mine, Suki’s family didn’t eat meat, not even eggs, so I was fascinated by their food. Her mother would cook up dishes using lentils and other pulses, which didn’t look very nice but tasted delicious. She spiced the food in a similar way to us, but unlike my mum, who tended to take shortcuts, she made all her own food from scratch, including pakoras and samosas.

Once when I was invited for tea Suki’s mum was running late and didn’t have time to cook. When she called us in to eat I was amazed to see plates of piping hot orange food, which looked like nothing I’d ever seen before.

‘What is it?’ I asked Suki, prodding with my fork at a round object coated in a thick gooey orangey-red sauce.

‘What, you’ve never had this before?’ Suki gasped.

I shook my head. I’d never seen anything like it in my life. My mum didn’t cook Western food.

‘Mum,’ Suki called to her mother, who was still busy in the kitchen. ‘It’s Nabila – she’s never had beans on toast before!’

I could hear Suki’s mum chuckling to herself in the kitchen and I felt silly.

‘Try some,’ Suki urged, scooping a forkful off her own plate before cramming it into her mouth. ‘Hmmm, it’s lovely.’

Reluctantly, I let the orange food slide into my mouth.

‘Hmmm, it’s lovely,’ I agreed, copying Suki. I shut my eyes and allowed the creamy beans to slide down the back of my throat and found they were, in fact, very good.

At that moment, Suki’s mother walked in. ‘Everything okay?’

‘It’s delicious!’ I said, licking the tomato sauce from my lips. ‘Can I have beans on toast every time I come here?’

Suki’s mother laughed and disappeared back to the kitchen.

After that, I loved going to Suki’s house for tea and I’d always ask for beans on toast.

Back at home, Mum had endless pots of meat curry on the boil. There were always scraps of meat from the butchers’ shop that needed to be used up. She made a legendary chicken curry, with lots of fresh coriander, and she would also cook curried lamb and goat. She was a pretty good cook.

My favourite dish was a gorgeous rice pudding, which I called ‘Mum’s rainbow rice’. I’d sit and watch as she mixed cooked rice, raisins, sultanas and coconut, before adding droplets of food colouring, using every colour you could think of. As she dripped them in one by one, the colours would bleed and be absorbed into each particle of rice, but before they became too blurred Mum would grab the bowl and flip it, mixing the rice in on itself. The colours would soak in and create what I called ‘rainbow rice’.

At six years old, Suki was a year older than me, but our lives were almost identical, apart from our religions. Like me, she was the only girl in a family of four brothers, but, unlike mine, hers were dashing and exciting. They never cut their hair. Instead they wore it in a bun under a dark fabric turban. I’d never see her brothers brush or comb their hair and I was always tempted to peek under their turbans to see if theirs was as long as mine. Their hair was sacred to them and I understood that because I’d never had mine cut either. I sometimes wondered if I should put my hair up under a hat or something so I could be just like my friends.

Despite her evening classes, Mum still couldn’t read or write very much English, but our Sikh neighbours took her under their wing and helped her. To our horror, they taught her how to knit and crochet, which meant we got even more hand-made clothes. Soon my brothers were moaning about all the outfits she was churning out at an alarming rate. They hated the fact that she made them all dress the same. Now, when they walked down the street everyone could tell they were brothers. There was no getting away from it. The stiff, brown home-made shorts were horrid, but the itchy pullovers were even worse.

‘I hate these clothes! We look stupid,’ Saeed moaned to me in the garden one day. I covered my mouth to stifle a laugh. I’d been wearing Mum’s creations all my life and, although my dresses were beautiful, they could sometimes be a bit garish. Now it was someone else’s turn to suffer.

My mum was happy to have Sikh friends and during the six years we lived in Sikh Street she became great friends with Suki’s mum, but at the same time she made it clear to me that I would never be allowed to marry a Sikh. In her eyes that would be wrong. It would cross too many barriers. It seemed odd to me at the time that mum could choose her own friends while, as a Muslim woman, she couldn’t choose her own husband, but I always knew it would be the same for me. When the time came, Mum and Dad would choose my husband.

The two women took it in turns to walk Suki and me across the road to the local infant school. I loved school. I was one of only a handful of Muslim girls but I was treated exactly the same as everyone else. My schoolmates saw beyond my religion. Friendship was the most important thing to us and I was sure that Suki and I would stay friends forever.

When Suki’s family went to visit the Sikh temple I often went with them. The temple was a tall and imposing building. The outside was painted bright yellow – the colour of sunshine – and it had an Indian flag hoisted high in the air, which flapped around proudly in the breeze as if it was in the hands of a brave soldier. There were ornate carvings on the outside, and a domed roof on top. I thought it was beautiful.

The Sikh temple was very different to the mosque where my father went every Friday. For a start, the women I knew didn’t pray at the mosque, only men, but the Sikh temple was open to everyone. It was a large open room with white sheets covering the floor, like a bigger version of Suki’s garage back at home. As with a mosque, everyone would have to remove their shoes at the door and cover their heads. We would then have to bow to the holy book, and make an offering of money. I never had any money but I would pretend, along with Suki. It reminded me of playing shops.

You could sit wherever you wanted but the women tended to sit together so they could all have a good gossip. Everyone knelt on the sheets to pray and the holy book was held high above our heads on a plinth.

My strongest memory of the Sikh temple is that it had a very happy atmosphere. The man at the front sang as he recited prayers and the worshippers would sing back and join in with him. I found it thrilling that we all got the chance to sing out loud, which we could never do in the mosque.

Members of the congregation brought food from home with them, and once the service was over they stood up and began to lay it out. It was served by both men and women. I thought how much Habib would hate it that the women and girls were treated the same as men and boys. For me it was fantastic, because not only did I get to sing and eat, but I also got to sit next to my best friend. I thought how much fun it would be to be a Sikh. After going to the temple, all I wanted to do was learn how to become a Sikh. Their lives seemed so pure and good. I loved being at Suki’s house because there I could pretend to be one of them.

Then one day all that changed. Dad had been working long shifts back to back and the lack of sleep was getting to him. He realised that he couldn’t go on working all day as a butcher and all night as a labourer. Something had to give, and that something was our home. By selling the shop and our old home, he would have enough money to buy a cheaper but bigger house somewhere else. He would keep his job as a labourer, but this way he would have more time to spend with us.

‘Nabila, get your shoes on. Your father is taking us all to see a house,’ Mum announced one evening.

‘A house? Where?’ I asked suspiciously.

‘It’s not far,’ she explained, without giving too much away. No doubt she sensed that trouble lay ahead.

‘But I’m not moving. I’m not leaving Suki and her family,’ I wailed.

‘We’re only going to look at it. Now do as you’re told, put on your shoes and get in the car.’

Dad never lost his temper but I could tell that he really wanted us to see this house, so I agreed to go.

Ten minutes later we arrived outside a huge Victorian house on a main road in a different area of town. It was smelly, noisy and dirty because the rush-hour traffic ran straight past outside. The patch of front garden underneath the window was tiny, not much bigger than a postage stamp.

‘Let’s go in,’ Dad said enthusiastically, as my brothers and I stood on tiptoe, trying to peer through the dirty bay window at the front of the ramshackle house. A filthy torn net curtain hung limply in the grotty window as if it was trying to conceal the horrible contents within. The whole building looked broken and unloved, as if it had been deserted for years. It looked like a haunted house from one of the cartoons on telly. It made me feel scared just to be there.

‘Who lives here?’ my brother asked.

‘No one,’ Dad replied. ‘That’s why we’ve bought it!’

‘Bought it!’ I gasped, my mind racing with fear that I’d never see Suki or her family again.

Dad turned to give me one of his looks, so I fell silent. He put his hand in his coat pocket and pulled out a couple of large metal keys I’d never seen before; they were the keys to this haunted house. I wondered how long he’d had those keys in his pocket and how long ago he’d bought this awful building.

He placed the largest metal key in the lock and turned it. The front door creaked open to reveal a dark and damp interior. It smelt musty but it also smelt of something else – grass or plants. I was confused. As my eyes adjusted in the half light, I spotted the reason. There was a bush growing in a corner of the front room! The plaster had fallen from the walls and there were big chunks of it all over the floor. Instead of plaster, the walls were covered in twisted brown roots where a tree was sprouting from the middle of the wall! The windows at the back of the house were as grubby as the big bay window at the front but, unlike the bay, they were all cracked and broken.

‘It’s got a garden inside,’ I whispered confidentially to my brother Asif, who was standing by my side, his mouth hanging wide open in horror.

The front room had no ceiling. Instead there was a huge gaping hole and daylight shone in. One of the upstairs bedrooms had a similar open-roofed arrangement. How could Dad even bring us to such a dangerous and horrible place, never mind buy it?

‘It needs a bit of work,’ he agreed, sensing our shock. He stroked the bristles on his chin thoughtfully as he contemplated the huge task that lay ahead. I looked back at him in astonishment. Dad was a builder but he wasn’t a miracle worker!

My brothers were still wide-eyed, surveying the wrack and ruin that surrounded us.

‘But I reckon with a bit of hard work I can do it!’ Dad concluded. ‘Look at all the extra room we will have.’

He told us later that it had been empty for almost nine years and I wondered why it had been so unloved. Was it haunted?

I hated the house from the moment I saw it. It was true there was going to be plenty of space for us there but all I craved was the comfort of our cramped terraced house back in lovely Sikh Street. I felt sad to be there and moving away from Suki. I wandered glumly to the window at the back of the house, which overlooked a huge back garden. I thought what an unhappy garden it was – unloved and abandoned. It was so full and overgrown that it reminded me of a jungle. I convinced myself that the grass was so long there must be snakes hidden in it.

I was still daydreaming, looking out at the long grass and the messy, entangled shrubs, when I saw something move between the leaves. They shifted and parted as a weight brushed against them. I rubbed my eyes and continued to stare hard through the filmy windowpane. At first I thought I was seeing things, that it was a trick of the light, and then I spotted it – a wolf! I screamed in horror.

It had a pointy nose, beady eyes and a long pink tongue, which dangled limply down from the corner of its mouth, covering razor-sharp teeth. To me, recently turned six years old, it looked vicious and hungry. I was convinced it was a sign – a sign that we shouldn’t live in this horrible scary house.

‘I’ve just seen a wolf!’ I shouted dramatically. My heart was beating so fast I thought it would leap right through my chest wall.

My brothers came running into the room just in time to see the little ‘wolf’ slip back through a bush and disappear out of sight.

‘You idiot, Nabila,’ Asif said. ‘That’s a fox, not a wolf.’ They sniggered amongst themselves, saving it up as one more thing they could tease me about.

I didn’t believe him. I ran upstairs to find my parents and tell them all about the wolf, but they didn’t take much notice. Mum was too busy with a tape measure trying to work out where her new bed would go. She was smiling to herself, delighted with all this new space she could fill.

‘It’s going to be great here,’ she sighed.

But my heart was still in my mouth. This place was horrible. It looked like an old haunted house and now there were wild animals living in the garden.

‘I hate it,’ I sobbed, as Mum brushed my hair later that night back at our old home. ‘Why do we have to leave here? Why do I have to leave my best friend?’

‘But Nabila, you’ll have your own bedroom,’ she soothed. ‘We’ll have so much more space there. Won’t that be lovely?’

She hoped that I’d take the bait, but I didn’t. I didn’t want to. I didn’t care about having my own bedroom, even though I desperately wanted one – not if it meant leaving our lovely neighbourhood and moving to the horrible new house. I didn’t want to live in a house with wolves in the garden. I wanted to stay here with my friends, the Sikhs.

But the decision had already been made. Dad started work on the new house and was gone from dawn till dusk trying to make it habitable. He did most of the work himself, although my older brothers helped to mix cement and paint the walls.

Three months later it was ready for us to move in. Dad stuck tape across the last cardboard box and gave it a satisfied tap. Our lives had been packed up and shipped out in a series of bags and cardboard boxes.

‘That’s the last of it,’ he called to Mum.

I watched as Dad struggled out to the car parked in the street outside. He turned sideways as he shuffled the heavy box of breakables into the open boot. We were officially leaving. I couldn’t believe it. This was the moment I’d been dreading.

Suddenly fear gripped me. I glanced out of the back window towards Suki’s home. The back door was open. I saw my chance and ran all the way across the road to my best friend’s house without looking back. Her mother answered the front door and smiled warmly as she looked down at me, breathless and seeming a little lost, on her doorstep. She invited me in and I saw my chance and dashed into the front room, whereupon I refused to move.

Moments later, my mother came to the door asking for me. Suki’s mum ushered her in and pointed towards me, but I wouldn’t budge.

‘I’m not leaving, I’m staying here. You can’t make me go!’ I screamed, and began to sob.

The two women looked at me sadly. Suki came and wrapped her arms tightly around me and she began to cry as well. We didn’t want to be parted; we wanted to stay best friends forever, just as we’d always promised to be.

‘I want to live here with Suki and her family,’ I insisted. Big, hot, wet, angry tears stung my skin as they rolled down my cheeks and dripped onto the carpet below.

‘Nabila,’ Mum tried to reason, ‘come on. You can see Suki any time. Your father is waiting outside in the car with your brothers and if you don’t hurry up we’re going to be late.’ She was beginning to lose her temper.

But I was adamant. ‘I don’t care. I’m not living there! I want to live here in this house. I love this house.’

I looked over at Suki, who was sobbing silently, and knew she felt exactly the same way. Then I looked up at Suki’s mother with big, brown pleading eyes and she smiled gently. I hoped this might be like it was in the storybooks, that Suki’s mum might offer to adopt me and save me from the haunted house and the wolf in the garden. I hoped that she would let me move in with them here, where I would live happily ever after. But instead she remained silent.

Mum tried to reason with me, but the clock was ticking and Dad was waiting in the car.

‘Come on,’ she said, taking my hand in hers.

‘No!’ I replied defiantly before launching myself at the huge stone fireplace. I stretched my arms as wide as I could so that I was gripping the corners of the stone. ‘You can’t make me!’ I shut my eyes, hoping this would make my mother disappear and leave me here.

Mum tugged, but I resisted and clung to the fireplace like a limpet. Soon there was a right old commotion. Suki’s brothers heard the racket and came running downstairs to see what was happening. By now, spurred on by an audience, I was in full flow. One of the boys started to giggle but he was silenced by a stern look from his mother.

Finally, Mum wrapped her arms around my tiny waist and gave one last big tug, which extricated me from the fireplace. The palms of my hands smarted where the stone had scraped against them. The rough edges had grazed them slightly and they were red and sore. I licked them, but that made them sting even more. This was the worst day of my life.

‘Come on, Nabila, we need to leave now,’ Mum said crossly. Then her voice softened a little. ‘She can see Suki any time, can’t she?’ she asked Suki’s mum.

‘Of course she can.’

That day, I left our familiar old street and our wonderful friends behind. Little did I know the nightmares that awaited me at the new house, or the bigger demons that lay ahead, ready to snatch me from my happy and safe little world.