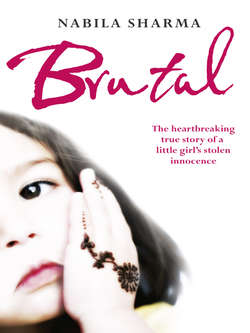

Читать книгу Brutal: The Heartbreaking True Story of a Little Girl’s Stolen Innocence - Nabila Sharma - Страница 8

Chapter 4 The Mosque

ОглавлениеI had just turned seven years old when I was told that I was to start going to the mosque. This was the age at which my brothers had started. I’d go every week night after school from five till seven in the evening, and I’d have to keep going until I had learned the entire Koran, which was a pretty daunting prospect. It was all part of being Muslim, though, so I accepted I had no choice. I told myself it would be exciting and different. I felt the butterflies fluttering in my stomach at the sheer thought of it, but at the same time it made me feel very grown up. It was a sign that I was growing older and wiser.

Besides, I was eager to learn the Koran. Muslims considered it the word of God and I knew that it was as important to us as the Bible is to Christians. My parents weren’t particularly religious: Dad went to mosque once a week, at a mosque on the other side of town where he met his friends, but Mum didn’t go at all. To me, learning the Koran was a challenge, something that I’d have to learn to be tested on later. I was excited about going to this mysterious new place with my brothers and without Mum and Dad. I resolved to try my very best at being a good Muslim. I wanted to make my parents proud of me.

Before I started, my father sat me on his lap. ‘Nabila, promise me you’ll work hard at the mosque?’

‘Yes, Dad, I promise.’

I knew it was important to him and I loved my dad so much that I’d have done anything to make him happy.

None of my friends from school went to a mosque so they all thought it was very exciting, but because of this I didn’t really know what to expect. Would there be handsome men dressed in lovely long robes like princes, waiting to teach us ancient religion?

I was nervous about the other children there. What would they be like? Would they be nice and friendly? Would I make more new friends? The more I thought about it, the more I wanted to start, until I was quite literally counting the days.

My brothers had been going to the mosque for a couple of years but they never talked to me about it. I wondered why. When I asked, Asif told me that they all hated going and I thought that was curious. But I was a girl and I told myself I was bound to enjoy it more than them. They hated everything apart from football and cricket.

Habib had been going to the mosque for so long that he was coming towards the end of his studies. He was fifteen years old and said to be a fine student. He’d read the whole Koran, and now he knew it off by heart. I heard him practising in his bedroom. I hoped that I’d be smart like Habib and that I’d be able to learn the Koran, just like him.

As the oldest, it would be Habib’s job to walk us all to the mosque. I felt sorry for him sometimes because he spent his life babysitting for us. This time he couldn’t object, though. I could spend time with my brothers and there was nothing they could do to get rid of me. This was a new chapter in my life and I planned to enjoy every single moment of it.

Before my first lesson at the mosque, Mum drew me aside and handed me a black cotton scarf. ‘This is to cover your head once you go inside. You must remember to wear it whenever you are in the mosque,’ she instructed. ‘You must be modest, Nabila.’

I took the scarf and tied it the way she showed me so that it covered my neck and hair and only my face was showing. You had to do this inside the mosque so that you didn’t attract men. All Muslim women did it. We were supposed to cover any part of us that might be deemed attractive. Mum had always made a huge fuss of my hair, so I understood that it was seen as something beautiful and, according to our religion, all beauty had to be covered inside the mosque. The scarf could only be removed once you left.

My mum didn’t wear a headscarf at home, but she always wore one when she was out in public. Like me, she had long, thick dark hair. Some other mums were much stricter and made their daughters wear a scarf everywhere except in the family home, but mine didn’t care as long as I covered my head in the mosque. Mum’s scarf was hot and it made my scalp itchy so I decided that as soon as I’d walked out of the mosque door I’d rip it straight off my head.

She also explained that there was a special rule that women and men had to be separated during prayer. She said it was to prevent them being distracted by ‘impure thoughts’. My brothers told me it was to stop something called ‘fornication’. I nodded knowingly despite the fact that at just seven years old I didn’t have a clue what they meant. Judging by Asif’s giggles, I assumed it was something very rude.

School finished at three-thirty so we had just enough time to run home and grab some tea before it was time to go. Before we left home, I washed myself in preparation for prayers, being careful to clean my feet, hands, face and body. Mum explained I had to be clean to pray and that this was something I’d have to do before every trip to the mosque.

That first evening she walked down the road with us. It was a cold evening and the wind blew an icy chill clean through me. I shivered and pulled my winter coat tighter against my body.

‘What’s it like at the mosque?’ I asked for the umpteenth time, but my brothers seemed curiously reluctant to say anything in front of Mum.

I knew I was to learn my lessons from someone called an imam, so I asked what he was like.

‘Very strict,’ said Asif. ‘He’s quite scary.’

I guessed they were exaggerating and making it up to frighten me, just as they had with the witch in the wallpaper. I couldn’t get them to say anything more, though, so I soon gave up trying.

The mosque was around half a mile away from where we lived on the opposite side of the road. Even though the road was long and straight, you couldn’t see the mosque from my bedroom because it was too far and it was hidden by several roundabouts on the way. I’d imagined that it was going to be a big beautiful building, just like Suki’s temple, but it wasn’t. It was new and hadn’t long been built. There were no domes or carvings on it. Instead it was a three-storey, white-painted building with a sky-blue front door, and it looked like any old office building. It stood between a house and a factory, just by a busy main junction, which was controlled by traffic lights.

As we arrived, the lights turned red and several cars queued up in a line. The faces of the white families pressed up against their car windows to gaze at the mosque as if it was a place of mystery. As I watched them, I thought to myself that I was just like the children in those cars – I didn’t know any more about this place than they did.

I was looking up at the mosque when Mum tapped me on the shoulder and gestured towards my head. I remembered the black cotton scarf, which was folded neatly in my coat pocket. I pulled it out and shook it until it was fully open. The wind blew, making the cloth arch out like a mini parachute. I wrapped it snugly around my head, securing it with a fat knot under my chin. It was far too big, even though I had acres of hair, so I tucked it under the edges of my collar to hide the rest of my neck. I wanted to be sure to create a good impression right from the start.

My mother turned to leave us at the mosque door. ‘Just do as your brothers tell you,’ she instructed, before planting a quick kiss on my forehead, and with that she walked away.

I stood and waved after her, feeling forlorn. I’d been excited for ages about this moment but now, even though I was there with my four brothers, I suddenly felt very alone.

Habib sighed and pushed open the heavy front door. Saeed, Tariq and Asif followed him and then it was my turn. The door was too heavy for me to hold so it slipped from my grasp and came crashing to a close with a loud bang. The noise echoed around the empty building and Saeed shot me a look of disgust. I’d already broken the first rule – to be quiet – and I’d only just set foot in the place.

We were the first children to arrive that night. I watched my brothers and copied what they did. As soon as they were inside the hall they removed their shoes, placing them near the door. I noticed that they left their school socks on so I did the same and placed my black shoes neatly alongside theirs. I’d done this many times before at Suki’s house and again at the Sikh temple. I hoped that the mosque would be as joyful as the lovely temple. Maybe there would be singing. If we were lucky, we might even get a bite to eat. However, as soon as I stepped inside the mosque and saw the dreary interior I knew this was going to be very different from Suki’s lovely temple.

Inside there was a large open carpeted space and very little furniture. Long wooden benches had been pushed hard against the sides of the room and above them hung a long bookshelf, which contained all the children’s prayer books. It wasn’t a happy place like the temple; I could tell that this was a serious place – even more serious than the headmaster’s office at school. Suddenly, I began to feel very nervous.

The noise of the heavy banging door had brought the imam down to greet us. He was a tall, gruff-looking man, smartly dressed in a grey tunic and trousers. Like us, he wasn’t wearing shoes. He came towards us but there were no smiles or warm welcomes.

‘Don’t say anything, just follow what we do,’ Habib hissed at me, and I did as I was told, terrified that I’d somehow get it wrong.

Habib straightened his back and shoulders and tried to look confident. He was the eldest, so he wanted to set a good example. He walked towards the imam, holding out his hand. I caught sight of his expression and he looked different somehow, as though he was a little nervous. This was maybe the only time in his life when Habib wasn’t in charge. It shocked me. Habib wasn’t normally frightened of anyone but he looked very wary of this man.

I remembered Asif warning me on the way there: ‘You don’t ever disrespect the imam.’

The imam took Habib’s hand in his and shook it formally.

Habib spoke: ‘Salaam alaikum.’

The imam’s expression didn’t change as he bowed his head politely and replied: ‘Alaikum salaam.’

‘What does it mean?’ I whispered to Asif.

He leaned in close, trying to speak quietly, but his words carried across the mosque in a whispered echo: ‘It’s an Islamic greeting. It means peace be unto you.’

Habib shot us a sideways look, warning us to be quiet.

Next it was Saeed’s turn to shake hands, then Tariq’s, Asif’s, and finally mine. I’d memorised the greeting but I was a shy little girl and frightened that I would somehow get it wrong. The imam sensed my fear and was kind towards me, and thankfully I didn’t mess up the words.

Once we had all greeted the imam, Habib shepherded us to the side of the room and pointed at some prayer books that were stored in a pile on the windowsill.

‘Pick up your prayer book,’ he told the others. But I didn’t know what to do – I didn’t have a prayer book.

The imam came over. ‘Just watch and follow what your brothers do,’ he said gently in Urdu, but I still didn’t know what to do about the book because their books all had their names written on the front.

The imam sorted through the stack of books on the windowsill until he found a suitable one. He pulled it from the pile and held it in his hands, flicking quickly through each page to assess how difficult it was.

‘Here,’ he said, ‘use this one.’

I glanced at the book in my hands and saw it was written in Urdu. With the imam only speaking to us in Urdu and the prayer books all in that language, I would have to try to learn more of it. I knew enough to understand Mum when she was shouting at us in her native language, but now I needed to learn it properly so I could recognise Urdu words in books.

The book I’d been given seemed too childish for my age. It had pictures of people kneeling on prayer mats, a dog, a boy holding an apple, a boy brushing his teeth, a drawing of a cow, even a man banging a drum, but when I looked at the squiggles by the drawings they meant nothing to me. They weren’t like the letters I’d learned in school so I couldn’t spell them out. How would I ever understand them?

I was sitting trying to make sense of the shapes and words in the book when the mosque door flew open and crowds of children – around seventy of them – came flooding in. Soon the room was bursting with kids. They’d been brought in by a special mosque bus from different parts of town and they filled the hall. The noise was deafening, as each and every one of them began to chatter at the same time. Some went off to wash themselves before settling down so that prayers could begin. Suddenly the imam spoke and everything went quiet. A hush descended across the room, and now it was the silence that was deafening.

The new arrivals sat on the floor and waited to be told what to do. Each one had a prayer book in his or her hands. I scanned the faces. There were all ages here, with primary-school kids sitting crossed-legged next to teenagers. Some of the boys were already sprouting dark hairs on their chins and top lips and looked more like young men than boys. These children lived in a different area to me and my brothers. Everyone seemed to know everyone else. I felt like the new girl on her first day at school again. But then, I suppose I was. Suddenly I felt very small within this big crowd.

I thought of my mum back home, cooking in the kitchen, and wished she were here with me now, holding my hand like she used to do when I was little. Nowadays the only times she held my hand were when we crossed the road, or when I didn’t want to leave somewhere and she was dragging me out. She wasn’t an affectionate, demonstrative mother in the way that some of my friends’ mums were. Dad was the affectionate parent.

The whole room stayed quiet while the imam took his place at the front. He knelt behind a small wooden table, which stood only inches from the ground, just high enough to get his knees under. I tried not to laugh. To me it looked like a little dolly’s table.

The imam told us to read and memorise a page of the Koran. I looked down at the squiggles on the page in front of me and couldn’t understand a word of it. Asif saw me struggling and shuffled in closer to help. He pointed at the picture and then at the word, reading each one out slowly so that I could memorise it. I tried my best but there was so much to learn that I didn’t know where to begin.

Other than Asif, I didn’t speak a word to anyone. I was scared but still a little excited. I didn’t have any friends here but it didn’t matter because I had my brothers and they would look after me. For the first couple of weeks I stuck to them like glue.

Later that evening, the imam handed me my very own Islamic prayer book, written in Arabic, Urdu and English. I felt extremely important. Inside there were prayers for everything: prayers for the sick, and prayers for when you were travelling on a train, bus or ship. I examined the list at the back of the book and saw there was a prayer for sleeping time, a prayer upon awakening, one for leaving the house, one for entering and leaving the mosque, even a prayer for going to the toilet! My head spun with it all. How on earth would I remember any of it?

Despite my worries, my first night at the mosque went fine. Mum was waiting by the front door when we got back.

‘Well?’ she asked. ‘How did it go?’ She pulled at the arms of my winter coat, freeing me from the sleeves, before hanging it on a nearby peg.

‘It was okay,’ I told her.

She looked disappointed. I think she’d expected more but, to be honest, I wasn’t sure what I thought of the mosque. I hadn’t really known what to expect, but whatever it had been it wasn’t like that. I suppose I was a little disappointed. I’d wanted it all to be as happy and joyful as it was at Suki’s temple. Instead it had been very boring and serious. Still, it was only my first time. Perhaps it would get better.

From that day onwards, Mum decided that Habib could take us to the mosque every time.

‘Keep an eye on them all,’ she instructed as we set off. I glanced up at Habib and he didn’t look happy at all.

‘I’m always having to look after you lot,’ he moaned as we walked along the pavement to the mosque. ‘I’m sick of it. Nabila, walk quicker,’ he snapped, picking on me for no reason at all. ‘We’re going to be late at this rate. You don’t want to make the imam angry, do you?’

Lessons started at five on the dot, and the last prayer was at seven, so Mum expected us back no later than seven-thirty.

When we were walking to the mosque without Mum that second day, my brothers told me lots of scary stories about the imam.

‘If he gets angry then you’d better watch out!’ Asif began.

Habib explained that the imam would think nothing of hitting the children, but it was always the boys, never the girls. He’d hit them with the back of his hand. During the first few weeks there I didn’t see him hit anyone myself but I believed every word my brothers said, even though the imam remained kind towards me. He was so tall that he looked like a giant, with a long white beard and hands as big as a shovel. I thought how much it would hurt if he whacked you with those hands. All the other children seemed frightened of him too, so I was careful not to stand out in any way or do anything to make him angry.

One night when I’d been there for a few weeks we were all sitting reading when the imam walked up behind a boy.

‘You’ve not been paying attention, have you?’ he scolded.

The boy looked up from his book and flinched when he saw the imam standing over him. He nodded his head weakly. ‘I have. I promise.’ He was so tense and nervous that his voice cracked when he spoke.

I glanced round at the other children but they just kept their heads down, as though they were trying to make themselves invisible. I couldn’t take my eyes off the boy. By now he was shaking. You could tell that the imam was furious.

‘You stupid boy!’ he shouted.

The boy’s eyes were wide with terror. I gasped as the teacher raised his hand high above his head.

‘No, please don’t!’ the lad pleaded. He cringed and raised his arms protectively.

I winced and shut my eyes as the imam brought his hand down hard, giving the boy’s head a vicious swipe. The slapping sound made my stomach somersault with fear.

The boy cried out in pain, and when I opened my eyes he was spread-eagled on the floor.

‘Sit up!’ the imam barked loudly.

The poor lad tried to pull himself back up but he wasn’t quick enough. The imam brought his hand down again, this time on the boy’s back. He yelped in pain, like a puppy that had just been stepped on.

I looked over at the other boys, at my brothers, and waited for someone to say something, but no one did. Instead they all kept their eyes down, pretending to read their prayer books.

I wished I was brave enough to grab the imam’s hand and try to stop him, but he was a stocky, scary-looking man and I wouldn’t have dared. Instead, I sat there like a coward, with all the other children, and I stared hard at my prayer book. My hands were shaking so much that the book trembled and I was scared that if the imam saw them he would start on me.

‘Don’t look, Nabila. Just keep your eyes down,’ I told myself.

But I couldn’t help looking up at the boy, who had now pulled himself into sitting position. He was clutching his back and had tears in his eyes.

‘Now read!’ the imam instructed, pointing towards the boy’s prayer book.

The boy nodded and pretended to read, but there were tears rolling down his cheeks. I could see them dripping onto the pages and I was shocked because I’d never seen a boy cry before. My brothers would argue and fight but they never cried; crying was for girls. I felt embarrassed and sorry for this boy. I wanted to go over and see if he was okay but I didn’t dare move. Like the others, I was frozen to the spot.

On the way home that night, I asked my brothers about the boy.

‘The imam beats him all the time,’ Habib told me. ‘He’s slow. He gets things wrong and it makes the imam angry. And when he gets angry, he beats you.’

I saw an entirely different side to that imam who had been so nice to me on my first day.

‘Don’t worry, he won’t beat you,’ Saeed continued. ‘He never hits girls.’

I breathed a sigh of relief. That was something at least.

‘Have any of you been beaten?’ I asked.

They all laughed as if sharing a special joke between them.

‘Yes,’ Habib replied, ‘we’ve all been hit by the imam. But usually he just gives you a quick slap around the back of the head. That’s why you must be good, Nabila. If you’re not good you will be punished.’

I was terrified and decided that going to the mosque was even worse than going to see the headmaster at school; at least he didn’t hit you.

‘What do people’s parents say?’ I asked.

Habib stopped in his tracks and turned to me. ‘That’s the whole point, don’t you see? They send us here to learn. If you don’t learn, you get punished. If you are punished then they think it’s for your own good. Everyone has to do what the imam says. All Muslims do. It’s just how it is.’

‘But it’s wrong,’ I insisted. Mum sometimes slapped the boys round the back of the head but they were just little slaps. She wouldn’t hit them hard enough to knock them over. If she was really cross she’d slap me on the back of the legs, but she wasn’t as strict with me as with the boys so that didn’t happen very often.

Habib nodded his head. ‘Maybe, but the imam is powerful. Everyone’s frightened of him, even the parents. You must always do what he tells you.’

After that, I saw more and more beatings. Boys were pushed, shoved, scolded and slapped for not learning their prayers or just for getting them wrong. Thankfully, that particular imam didn’t stay long. He left and over the next couple of months our classes were taken by lots of different imams. You never knew who would be waiting to greet you with the customary handshake when you arrived at the mosque. Maybe it’s because it wasn’t a very smart or prestigious mosque but they couldn’t seem to find anyone who would take over on a permanent basis. At least the replacements weren’t violent like that first one, but still I worried each time we got a new one in case he would be rough.

The novelty of going there soon wore off and it became somewhere to fear rather than enjoy. It didn’t seem fair that after the school bell rang and all the other children were going home for a relaxing evening we had to go on to yet another, tougher school.

When I’d been there for a couple of months Habib and Saeed stopped going altogether. Habib had come to the end of his studies, while Saeed just made up his mind that he’d had enough. He’d always been a rebel and when he turned fourteen he decided he didn’t have time for this nonsense any more. I was sure he’d get into trouble but my parents knew they couldn’t force him to do anything he didn’t want to do, so nothing more was said.

Now I walked to the mosque with Tariq and Asif, but before long an incident occurred that meant Tariq had to leave as well.

One evening he was caught talking when he should have been reading his prayer book. He was still so busy chatting that he didn’t even see the imam approaching silently from behind. The slapping sound as the imam whacked Tariq across the head was so loud that it echoed around the room and made everyone look up from their prayer books. Tariq reeled forwards, almost hitting the wooden floor. I gasped because I knew Tariq. He was tough and fearless and I was sure he’d fight back.

The imam stood there waiting for my brother to cower and apologise, but he didn’t. Instead, Tariq got to his feet and squared up to the bully. The teacher was stunned. Tariq was tall for his age and had the build of a man. He refused to move but just stood there, looking the holy man defiantly in the eye. No one pushed Tariq around.

The children sat open-mouthed as they watched events unfold in front of them. They’d never seen a child standing up to an imam before!

Suddenly, the imam lurched forwards and slapped Tariq again. The slap was hard and was meant to make him sit down, but Tariq hit back with a punch that caused our teacher to fall to the ground, where he landed in a shocked and dishevelled heap.

The imam struggled to his feet and glared at Tariq, demanding that he sit down. Again, Tariq refused. He was furious, and I knew from past experience that he would fight to the bitter end if he had to.

The teacher glanced at my brother and then back at the rest of us. We quickly lowered our heads, pretending to read, because we didn’t want to be next. The imam knew he’d been shamed in front of us all by a young boy. Tariq was only twelve years old but he was stronger than the imam and the man realised he was beaten. He pointed weakly towards the door and told my brother to leave. Suddenly, our teacher looked very old and pathetic. He looked like the school bully who’d just been beaten up by a new and stronger boy. That boy was my brave brother. My heart swelled with pride.

Tariq shot the imam one last look of disgust before grabbing his shoes and slamming the mosque door behind him. He’d had enough of the beatings. He left that day and never came back again.

I thought the imam might call my parents to tell them what Tariq had done, but he didn’t. Maybe he was embarrassed to have to admit he was beaten by him.

I missed Tariq at the mosque because, of all my brothers, he was my protector, the one who made me feel safe. With him around no one would mess with me, but now that he wasn’t there I felt more vulnerable. I still had Asif, of course, but I wondered how long it would be before he grew tired of this horrible place. I had already grown to hate the mosque; to me, it felt more and more like a prison each day.