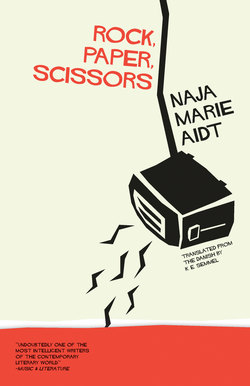

Читать книгу Rock, Paper, Scissors - Naja Marie Aidt - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA man cuts across the street in the city center. It’s drizzling. The traffic is earsplitting and intense, from shouting to dogs barking, from roadwork to the wailing of ambulances and the cooing of doves, from children screaming in their strollers to the metro rumbling beneath the streets, from hyperactive teenagers to the muttering homeless, from buses to street hawkers. Thomas crosses the street, a thin leather portfolio tucked under one arm, an umbrella under the other, and on his heels a plump, blonde woman hustles to match his pace. When she’s almost at his side she clutches his jacket, her cotton coat flapping behind her like a tail or a kite, and glances about wildly. A car races toward them at high speed. She gasps and lunges ahead, and at last they’re safe on the sidewalk, and Jenny lets go of Thomas. She says, “Can’t you use the crosswalk like a normal person? You almost got me killed.” Her eyes are wide and bright.

“Have you been crying?”

“I wasn’t crying.”

“It looked like you were crying back there.”

“Maybe I was crying on the inside. I was dying of hunger.” She raises her chin defiantly and begins to walk. Thomas follows. They head down a side street, away from the noise, a long, narrow street, poorly lit. It’s 6:30 P.M. and darkness expands around them. The air is cool. A raindrop pelts Thomas’s cheek, and before long they’re seated opposite one other at a table in a small restaurant. Thomas’s eyes roam across the objects between them: a green ceramic bowl filled with olive oil, a breadbasket, salt and pepper shakers, a carafe of water, and two mismatched glasses. Jenny’s chubby white hand fidgets with a napkin. Then she leans back and looks at him. “What did you think about the lawyer? Should we hire him?”

“Do we have a choice?”

“I guess not. Why were you so late?”

“I don’t know. Maybe I was hesitant.”

“Hesitant? Why hesitant?”

He smiles at her and lights a cigarette. “Does it even matter now?”

“Do you have to smoke?”

“Yes.”

“Are you even allowed to smoke here?”

“Yes. What are you going to eat? You want a glass of wine?”

“I want a Bloody Mary. And pasta with pancetta. And a salad. Remember the olives we had the last time we were here? You think we can get them again?”

The waiter, a stooped older man with wavy black hair, takes their orders and disappears into the kitchen. When the door swings open, Thomas sees two young men, one hunched over some steaming pots, the other grappling with a frying pan. In the warmth of the kitchen, their faces gleam with sweat. But it’s cool in the high-ceilinged room they’re in. Thomas shivers. A middle-aged woman behind the bar polishes drinking glasses. The restaurant isn’t even half full. “Remember when Dad brought us here the night of the accident, after you’d been to the emergency room? We sat over there.” Jenny points at a table next to the window. “I think it must’ve been this same waiter, back when he was young. You were pale as a sheet. How old were we?”

“I was eleven, you were nine.”

“And we got to order whatever we wanted. All I ate was chocolate cake. Three slices.” She laughs suddenly and loudly. “Ha! You were pale as a sheet, though nothing had happened. Nothing serious. Bumps and bruises. Just a few bumps and bruises.”

The waiter sets steaming plates before them. The bartender places a red drink, a pallid stalk of celery poking out of it, in the middle of the table as if it were meant to be shared.

“Just a few bumps and bruises,” Thomas repeats slowly, pushing the drink toward Jenny. “That’s one way to look at it.”

“Oh, don’t be so dramatic. Eat your food. Cheers.”

She raises her Bloody Mary so that the lamplight shines through the red liquid. “Ha! Just a few bumps and bruises!”

“That actually looks like blood,” he says, pointing at the glass with his fork. Then he bores into his oxtail and shovels the sauce with his knife. The waiter limps back carrying a half-empty bottle of red wine along with a plate of olives. But Jenny isn’t happy. “They aren’t anything like the ones we had last time. Plain, tasteless. I bet they got them at the local supermarket. Try them yourself. Everything gets worse over time, everything, everything. Doesn’t it?” Thomas refuses to try the tasteless olives. He takes a swig of wine, and says: “Dear Jenny, you’re always complaining. Everything doesn’t get worse over time, everything gets better. We’re rid of Dad, for one thing. Think about that. And he’ll never come back. Except in our most terrifying nightmares.”

“How can you be so mean? You’ve always been mean. It’s a constant, neither worse nor better with time. But everything else gets worse. Love and marriage. Our bodies fall apart. Hideous! Things get uglier. Doors, buildings, chairs, cars. And silverware.” She pokes her fork at him. “Yup, even silverware gets uglier and uglier, and people get uglier and uglier. Just think of Helena and Kristin’s twins, how they dress so tastelessly you wonder if it’s a joke. They sent a photograph at Christmas, Kristin must have taken it—she’s such a terrible photographer—and . . .” She stops abruptly, sets down her fork, and smoothes her shirtsleeves. Then she looks directly into his eyes. “You’re also getting uglier. You really are. You were handsome once. You looked like Mom and her brothers.”

“Can we talk about something a little more uplifting?” Thomas smiles at Jenny, but she shakes her head, and says: “I don’t know. I’m not doing so well. You think we can save a few odds and ends from Dad’s apartment before it’s cleaned out?”

“There’s nothing there, Jenny. Just a few ugly, ugly things.” He smiles again, and now she too smiles, despite herself. Her teeth are yellow, her mouth wide and red. A sudden gleam in her green eyes.

“I want the toaster. It’s special to me.”

“Then take it. No one will know. What do you want with an old toaster?”

“Come to think of it, did he have anything personal in his cell?”

Thomas lights another cigarette and shakes his head. The bartender’s playing some strange music, a kind of languid disco.

“A notebook and a stack of porn mags. His watch.”

“What was in the notebook?”

“Nothing. Doodles and some phone numbers.”

“He didn’t even have a photo of us?”

“Don’t be childish, Jenny. Of course he didn’t have a photo of us.”

“I want dessert. And coffee.”

Jenny orders ice cream and coffee for them both. She devours hers greedily, starting with the maraschino and then working her way through the layers of ice cream, chocolate syrup, and whipped cream. One moment she resembles a little girl, the next a broken, overweight prostitute. A charming prostitute, Thomas thinks, surprised. He imagines how she’ll look in twenty years. The skin of her cheeks will be slacker. Her hair will be thinner. Maybe her hands will shake. Casually he glances at his phone. No messages.

“How’s Alice?” he asks.

“She’s got a new boyfriend. Again. I don’t like him.” She licks the last of her ice cream off her spoon. “You should see how he gropes her in public. He’s reckless.” She looks out the window. It’s pouring now. Runnels of water stream down the enormous panes. “It’s not easy having kids, Thomas,” she says dreamily, still holding her spoon. Then she collects herself. “Well, anyway, I’ll go pick up the toaster tomorrow.” She tries to smile, but he can tell she’s on the verge of tears. He takes her hand and squeezes it, feigning solemnity:

“Take the bus right to his door, Jenny.”

She can’t help but laugh. A moment later, she squints at him, giving him a hard glare. “Okay,” she says. “Listen. This is how it was: We sat right over there, at the table by the window, and Dad said: ‘Order whatever you want.’ He didn’t care, he said. At first I didn’t believe him, but he was serious. You remember that? He snorted and groaned. Sweat dripped from his temples down his cheeks. Remember how sweat used to run down his temples? Who’d called him anyway?”

“You know. Someone from the emergency room. I waited for hours. Do we need to discuss this?”

“Yes, we do. Dad visited you in the emergency room, then what?”

“Jenny . . . let it go.” Thomas stares resignedly at her.

“Come on. Then what?”

“Something had happened. I sprained my left arm, banged my head, and injured some vertebrae.”

Jenny leans back smiling patronizingly, almost gleefully.

“It’s true,” Thomas goes on, annoyed. “And the first thing he said to me when he walked into the room was, ‘What the hell have you done now?’ He didn’t care that I’d been hit by a car. He thought it was my fault.”

“Did you walk in front of the car, or what?”

“No, and you know it.” Thomas feels anger surging in him, his voice growing shrill. “It was speeding, it turned the corner, it hit me, I landed on the hood. You know all that. Maybe the sun blinded him. It was spring.”

“Who was blinded by the sun?”

“The driver! But it wasn’t my fault.” Thomas sighs loudly. “I was going to buy bread . . .”

“Yes.” Jenny flares her nostrils and turns away, eyebrows lifted. “I waited for you in the hallway. Waited and waited. But you never came.”

“Like it was my fault!”

“I’m not talking about fault. I’m just saying you never came. I was so hungry my stomach hurt. I just sat there, squatting, leaning against the wall. Remember how dark it was in that foyer? How deep it was? The bulb on the ceiling, the brown walls? Ugh, they were really brown. When you were alone in there, it was like they were alive. There were shadows and . . . black holes.”

“Black holes?”

“Yes. Black holes. I was so scared.” Jenny’s eyes are moist now.

Thomas shrugs. He signals the waiter, orders another coffee.

“I was scared, Thomas,” Jenny repeats, earnestly. “Look at me.”

“He was wasted,” Thomas said.

“No, he wasn’t. You’re blowing things out of proportion again.”

“Yes, he was. He was wobbly on his feet. You think I couldn’t tell when he was drunk? And you could too. He stank. Listen, Jenny. I had a concussion, a black eye, a scraped head, and a sprained arm, and all he did was stand there wobbling and blustering like an idiot. He stared at me, he stared out the window, he sat down, and he stood up again. He hobbled around the room in that uneasy way that made us nervous, and that—”

Smiling, Jenny shakes her head.

Thomas points at her. “It made you nervous, no matter what you say.”

“But I wasn’t even there!” she interrupts him.

“No, but I was, and he just walked over to me and grabbed my arm. ‘Let’s go,’ he said, despite the fact they wanted me to spend the night at the hospital. It was embarrassing, but he didn’t care. He yanked me out of the bed and shoved me into the elevator. I remember that shove clearly, because I had so many bruises on my back. Then we went home and picked you up—”

“In a taxi,” Jenny interrupts.

“He didn’t say a word the whole ride.”

She straightens up when the waiter pours her coffee. She says, “I remember that. The taxi. How we drove here and could order whatever we wanted.”

“And why do you suppose that was? Was it a punishment or a celebration?”

“I don’t know. What do you mean by ‘punishment’? I ate as much chocolate cake as I could, but you,” Jenny points at him. “You just sat there moping—and what did you order again? Soup?” She snickers. “Soup! It made him angry. But c’mon, it’s so weird to order a ridiculous bowl of soup, the cheapest thing on the menu, when for once you could have whatever you wanted.”

“I was sick!” Thomas sets his cup heavily on the saucer. Then he lowers his voice. “Can we just drop this? Why do you want to talk about this?”

“Drop what? You had soup, you didn’t touch it, he got angry, and then you fell off the chair.”

“I fainted, Jenny. I was nauseated, I was freezing, I was in pain, my head was spinning, I couldn’t eat that fucking soup.” His voice is a savage hiss, but Jenny laughs again, lightheartedly.

“You fainted because you were hysterical! Don’t you think? That’s what I think.”

Thomas shakes his head, stares at Jenny, lights a cigarette, and blows air through his nose.

“Okay,” Jenny says. “We won’t talk about it anymore. But the chocolate cake was really good. And you were so pale when you came to. Ha! He almost had to carry you to the car, though he didn’t want to. Then, as if that wasn’t enough, you threw up on the living room carpet when we got home. All because of a few bumps and bruises.”

“It was a concussion!” Thomas practically shouts. “A concussion for God’s sake.”

They stare at each other a moment, then each loses focus. Thomas zones out, his eyes resting on two men bent over their pasta. One of the men dabs his mouth with his napkin; the other says something, and the two laugh at the private joke. Thomas smokes greedily and drains the last of his cold, bitter coffee. Jenny gnaws at her pinky nail. She goes to the bathroom. Thomas thinks of his father’s kitchen, the toaster. The smell of the kitchen, the sound the cupboard next to the stove made when you closed it, how it stuck when you tried to open it. And the toast that would pop up, almost always too burnt at the edges, was like coal against his teeth, like tinfoil. He asks for the check. Jenny returns and begins to rummage in her purse. She fishes out a tube and slathers her hands with cream. A faint odor of menthol spreads around them. Then she begins to talk about her night shifts at the nursing home. About her modest salary and Alice and her friends who eat all her food. “What am I going to do?” she says, raising her hands only to let them drop heavily to her side. Thomas is exhausted, doesn’t say much. He pays, and they say goodbye outside the restaurant. Jenny is under a red umbrella, and Thomas is under a black one. Rain lashes the sidewalk with such force that it bounces off as if it were coming from both above and below. She offers him a key. The word Dad is etched onto a small piece of blond wood attached to the key ring. “I’m going out there tomorrow,” she says.

“Say hi to Alice!” he calls out as she walks away. She raises her arm dismissively but doesn’t turn back. Maybe she’s begun to cry. For a moment he feels a prickling jab of tenderness for the plump, swaying body disappearing around the corner. Then disgust. Then tenderness again.

At home Patricia’s sitting in front of the computer, her coat on. Her striped scarf has fallen to the floor. She leans forward, craning her neck, her face to the screen. The hallway light spills into the half-lit living room. She’s put a bowl of oranges on the coffee table. The cat sleeps in the armchair. Thomas stands in the doorway observing her. “Hey,” he says finally. She glances up. “Oh, hi baby. I’m almost done. Sorry, it’s just these pictures for the catalog. The graphic designer keeps putting them in wrong . . .” She stares silently at the screen, he stares at her back. The living room: still life of woman with averted face. Thomas goes into the kitchen, where a tower of dishes is stacked up. He washes his hands and drinks a glass of water as he gazes out the window. He can see the river and the lights on the other side of it. A lightning bolt flashes across the sky, a thunderclap booms far away. It begins to rain. “How’d it go?” Patricia calls out. “Okay,” he mumbles, putting down his glass. He walks into the bedroom and sits on the bed. He picks up his pillow and buries his head in it. This is how I smell, he thinks, it’s me, this aroma, the smell is me, it’s what I give off and what I leave behind, traces of my aroma: me. I am here. I am in the pillow. It’s frightening. Then Patricia appears in the doorway. “What are you doing?” He tosses the pillow aside. “Is something wrong?” She’s taken off her coat, and her hair is gathered in a ponytail. There are wet splotches on the knees of her stonewashed jeans, and her mascara has left black marks around her eyes. Must be from the rain. “You look tired,” he says. “Have you even had dinner?” “I had a sandwich on the way home. We don’t have any bread.” She sits beside him. “You have sauce on your collar.” He nods. With her nail she scratches a little at the dried sauce. She strokes his cheek. She puts her arm around him. “Where’d you eat?” she asks softly. “At Luciano’s. Jenny insisted.” He puts his arm around her, and they sit like that for a while. He can’t stop thinking about how stiff and clumsy it feels. They undress in silence, she brushes her teeth, naked—he’s already in bed—and she brushes her hair. “How’s Jenny? Was she impossible? And what did the lawyer say?” Patricia sits on the edge of the bed and touches his arm. She has goose bumps on her thighs. Her dark hair scatters across her face when she yanks the hairband from her ponytail. “Are you free of your father’s debt?” He closes his eyes. His body is heavy as lead. His heart beats languidly, as though drugged.

“Yes. If there is any,” he says, his voice raspy. “We’ve renounced everything. There shouldn’t be any problem. The county will pay for his funeral. But Jenny’s insisting that we have a ceremony.”

“Oh, no.”

“Why ‘oh, no’?” He speaks with difficulty. It feels as though half his mouth is anesthetized. Patricia lies beside him on her back. The duvet rustles when she gathers it around her.

“It’s just . . . the people who’ll attend. You know. That guy Frank,” she says in disgust, “do you think he’ll come? I’m sure he will. And the fat one, what’s his name again?”

He’s almost asleep now, his leg jerking, halfway into a dream about a circus. In it he’s moving slowly through high grass, getting closer and closer. He hears music. The grass is crawling with grasshoppers.

“Thomas?” She tugs at his arm. “Thomas. We should have sex now. It’s been weeks.”

“I can’t,” he mumbles, “I’m sleeping . . .”

He hears her distant sigh, then rolls onto his side. And he’s back with the circus. A girl on a carousel screeches with joy; she resembles Jenny. He senses the grasshoppers’ presence, a tickle, a sound, at once claustrophobic and alluring, and in the dream he regards his dirty, sunburned hand and realizes that he’s a boy, not a man as he first thought.

The next morning he wakes at dawn. The sun’s shining through the slats in the blinds. Patricia’s fast asleep, her mouth open. Apparently she’s been pulling at her hair again, which she sometimes does in her sleep, because it’s completely rumpled on the left side. A strange habit. Carefully, he touches her shoulder. Her breasts look like two pink cupcakes. For a moment he feels a strong desire for her. Then it fades. He crawls out of bed, makes coffee, showers, shaves, and gets dressed. Patricia stumbles sleepy-eyed into the kitchen and sits at the little table in the corner. He pours her a glass of juice. “When will you get home tonight?” she asks. “Can you stop at the store on the way back? We don’t have anything. Buy some good bread.”

She has a late meeting, so they arrange to make dinner at eight. He slurps the last of his coffee, then kisses her neck and cheek; she pulls his mouth to hers and pushes her tongue into it. He’s brushed his teeth, she hasn’t. “Get a bottle of wine, too,” she says, smiling. He removes his coat from the hook and stuffs the folder under his arm. He leaves the umbrella. Outside the air is mild and fresh after last night’s rain, the plane trees’ dense cluster of branches providing comfortable shade all the way to the train station. He loves their mottled trunks. He smokes a cigarette, and feels wide awake. He cuts across the street. Thomas O’Mally Lindström cuts across the street whistling with the sparrows circling overhead, after which he turns the corner and disappears into the darkness, down a long, dingy stairwell on his way to the train.

Dressed in a light-blue shirt, Maloney kicks the coffee automat. His curly hair is still damp following his shower, or maybe it’s his sweat. Thomas suspects that he’s screwing Annie, their employee, and maybe they’ve just had a tryst in the back room. Maybe Maloney’s got high blood pressure. He’s grown heavier over the past few years, and he sure likes his fats and salts. These are the kinds of thoughts rumbling through Thomas’s head when Maloney shouts: “I hate this machine! Peter! Peter! Go get some coffee. Milk and sugar. You need money?”

Thomas shakes his head, smiling.

“It’s always on Fridays, have you noticed that? Always on fucking Friday when you fucking need your coffee the most. I’m calling the company to let them know they can pick up their machine and shove it up their asses. I won’t pay another penny on the installments for this piece of shit.” Maloney’s already on his way out of the office. “Are the deliveries arriving today? Did you talk to them?” he shouts. Thomas follows him. Maloney flicks the switch for the chandelier, Eva rolls up the vacuum’s hose; they exchange a greeting. She says, “Have a good weekend” in her oddly whispered, self-effacing way, bowing her head shyly—but what could she be shy about?—and dragging the vacuum cleaner into the hallway. She can’t be the one he’s fucking, Thomas thinks, inserting the key in the register. Now Maloney’s on the phone with the company that delivers their stock, and it sounds as if they aren’t coming today. He slams down the receiver and sighs. “Why does everything have to be so fucking difficult?” It’s a big store, a desirable location, and it’s been a paper and office supply shop for nearly one hundred years; they’ve maintained as much of the old, dark wood as possible. The chandelier hangs from the huge rosette on the ceiling, which is cleaned thoroughly with a toothbrush, and they’ve carefully renovated the built-in cabinetry with room for especially fine decorative paper and gold leaf. The broad wooden planks have been polished and lacquered. When they opened the store, Thomas spent weeks lying on the floor sealing the cracks with tar. That was a warm summer, he recalls, and I hadn’t met Patricia yet. Maloney was young and trim in those days, and he was dating a nougat-skinned beauty whom he consistently referred to as “the sex kitten.” In the evenings they drank beer at a café around the corner and discussed how rich they’d be if they did everything right. Right. What the hell is right? Thomas wonders. For a moment he feels the urge to kick the coffee automat—since it’ll have to be returned anyway. Instead he sits behind the counter and turns on the cash register screen. Pale sunlight cascades through the tall windows. Morning traffic rumbles in the distance. “Soon people won’t have any need for paper,” Maloney says. “Who writes a letter nowadays? Who can even write by hand? Tell me. And books? They’re on the way out, too. People sit around fiddling with their stupid digital devices on the train. Have you noticed that? Wuthering Heights and Thomas Mann. It’s a joke. He and the Brontë sisters would turn in their fucking graves.”

“Maybe they do.”

“What?”

“Turn in their graves.” Thomas looks out the window. Sees Peter balancing coffee cups and a bakery bag, a cigarette dangling from his mouth.

“Did you know that Peter smoked?”

“No. Nor do I fucking care,” Maloney says. “What a goddamn morning. I think I’ll go home.”

“That must be why he’s always chewing gum. To hide it. The smell.”

Maloney calms a little once he’s had two cups of coffee and gobbled a chocolate croissant. There’s an enormous zit on Peter’s cheek. Annie’s wearing a red dress that accentuates her wide hips; her arms are thick, and her mouth is small and narrow, with thin, tight lips. “Okay, we’re doing inventory today. You do rows one through four, Peter. Annie, you do the rest.” Thomas nods at her. “Don’t count the pasteboard. We’ve ordered more.”

“But they haven’t arrived yet,” Annie says.

“No, they haven’t,” Maloney says, sourly. “Turn in your lists to me before 1:00 P.M. We need to send our orders by 3:00.”

“It’s usually before 4:00, isn’t it?” Annie raises her chin and looks at Thomas.

“But today it’s before 3:00,” Maloney says, and Thomas asks: “Are we doing the books?”

Maloney nods, then dries his cheek with the back of his hand. “I’ll start.”

A moment of silence. Everyone’s thoughts seem to turn inward, sleepily holding their breath as if it was very warm. But it isn’t very warm.

“What time is it?” Peter asks.

Maloney points at the wall clock behind them.

“Oh, yeah,” Peter says. “Sorry.”

Annie stands and moves her big butt into the store.

They open at 9:00 A.M. Annie and Peter begin, shelf by shelf, holding their lists under their arms. They look like two well-behaved students. Or assistants at a library. But Annie already looks older than when they hired her only a year ago—as if working in the store has worn her down. Thomas cleans the pen and pencil jars. Standing behind the counter, he gazes around the high-ceilinged room, letting his eyes roam across the products. He thinks: Half of everything here is mine. I have done it right. Then the door opens, and a mother with two small boys enters. They’re looking for tissue paper, felt-tip pens, and a printer cartridge. Between customers Thomas reads the newspaper, and at 10:30 he goes out to the sidewalk to smoke. It’s windy. Rotten leaves billow in the air and swirl around the street; the sky is suddenly dark and overcast. Earlier he’d found a notice in the local paper: “Convict Found Dead in Prison.” He tore it out and shoved it in his pocket. As long as Maloney doesn’t start in about selling party supplies, he thinks, extinguishing his cigarette on the sole of his shoe. That has never been the purpose of Maloney & Lindström. I should also quit smoking.

Annie hands in her list before Peter does. Thomas is hungry. He drifts about aimlessly, adjusting things on shelves. Not surprisingly, the two small children left their greasy fingerprints on the silk paper. He flips over the two most visible packages. A group of twelve- or fourteen-year-old girls tumble through the door giggling and at once filling the store with their exclamations and shrill voices, their all-encompassing noise. With their eyes made up and clinking armbands. He doesn’t have the strength to deal with them. He makes eye contact with Annie and signals for her to watch them. It’s not unusual for girls that age to steal. Small flocks of girls, and always during lunch break. He suspects they go into all the stores on the street, one by one. Last time a girl stole a handful of panda bear erasers and one of the big electric pencil sharpeners. She had hidden them in her hat. He would have called her parents, but she cried in such a shameful, desperate way that he let her go. He finds Maloney staring out the office window. “What’s up?”

Maloney starts. “Halfway there.” Thomas closes the door and sits on the edge of desk. “Are you sleeping with Annie?” Maloney stares dumbly at him, then bursts into laughter. “Thomas!” he says, “What are you talking about? Annie! What thoughts you have in your little head.” Grinning, he leans back, stops laughing. He eyes Thomas. “What’s going on with your dad? Did you talk to the lawyer? Yesterday, right? Let’s go get some lunch.” Maloney’s in the habit of asking questions and not waiting for a response. They retrieve their coats from the hallway closet and tell Peter they’re going on break. Maloney orders a sandwich with extra bacon, Thomas the soup of the day and a salad. They sit in the far corner, as usual. “They’re coming to pick up the coffee automat on Tuesday,” Maloney says, shoving a rather too large bite (bacon smothered in mayonnaise) into his mouth with his finger. “I let them have it, this little underling who sounds like someone jammed a carrot up his ass, telling me all about the rules—when the fucking piece of shit doesn’t even work.”

“Maloney . . .”

“Someone has to make sure things work.”

“My sister’s taking the death pretty hard.” Thomas hears how formal he sounds—the death—but he can’t say “my father’s death.” He can’t say “my father.”

“Oh, Jenny with the blonde hair,” Maloney mumbles, chewing energetically. “I did bang her, though it was a long time ago now. But Annie? How could you think that? Ha! She’s gained weight, hasn’t she? Your sister? So has Annie for that matter.”

“She has to go to the apartment, she said.”

“Jenny’s so . . . emotional. Isn’t she? Tears and laughter mixed into one. It’s like she can’t quite control which emotions connect to which expressions. What is that called again?”

“Histrionic.”

“No, sensitive. It’s a charming character trait.” Maloney looks at him while cleaning his teeth with his tongue.

“It’s almost over, Tommy. When are you dumping him in the ground?”

“Tuesday.”

“I’ll come if you want me to. You haven’t touched your soup.” Maloney wipes his mouth with his napkin and drains his soda. With two fingers he lifts a leaf of lettuce from Thomas’s plate, then lets it drop. “I remember Jacques. His glistening gray suit. Was it grease? Was it greasy? Is that why it glistened?” He glances up from Thomas’s salad. “I’m coming to that shitty funeral, whether you want me to or not, okay?”

“Okay.”

They stop a moment to admire the show window, which they’re both happy with, before they enter the store. It’s 2:00 P.M. Customers are beginning to arrive. It’s already busy: Annie works efficiently behind the register, while Peter advises people, retrieves items from the storeroom, and crawls up the ladder if anyone wants something from the top shelves. Thomas feels a momentary pang in his stomach, a rapping in his soul, a delight for the store, for its bustle, for the fact that they actually own this place. That he’s made it this far. That he’s risen out of the shithole he grew up in. That the store’s actually successful, the employees, their employees, his shelving system (his own certain sense of style). That they don’t have carpet on the floor. Satisfaction for his satisfaction, oh, satisfaction for satisfaction. Because recently a kind of lethargy has crept into him, a certain undefined disquiet or boredom (is it boredom?). But at this moment a twinge, a pang, when he strolls through the store nodding at customers and warmly greeting the sweet visual artist with the studio around the corner; she’s looking for colored acrylics and can’t find the magenta or the ultramarine. He calls for Peter, and Peter immediately goes to the basement, and the visual artist smiles gratefully. Walk down the short hall, open the office door, get the rest of the accounting done before closing time. He’s just sat down to it when Jenny calls.

“Oh, Thomas . . .” He can’t tell whether she’s sniffling or there’s some other sound in the background. “Oh God, it looks awful here . . .”

“What looks awful?”

“This place looks AWFUL, Thomas.”

“Are you in the apartment?”

A strange sound emerges from her.

“Of course it looks awful there. What did you expect?”

She snorts hysterically.

“Call a taxi, Jenny, go home. I’m hanging up, and you’re calling a taxi. Okay?” He hears her sitting down on something soft and creaky. Must be the armchair.

“C’mon, Jenny.”

“I can’t.”

“You can’t what?”

“I can’t stand up.”

“But you just sat down.”

“How do you know that?”

“I can hear you.”

“What can you hear? You can’t hear anything! You have eyes in the back of your head, you spy!”

“You’re sitting in Dad’s moth-eaten armchair staring at the television.”

“There’s no television here anymore.” Her voice quivers. “Someone took the television, Thomas. The apartment’s been ransacked. Everything’s gone, everything. It’s so dusty here, so disgusting . . .”

“Of course it’s dusty. I’m hanging up now. Call a taxi.”

“Don’t you give me orders! You always give me orders. I’ve never been allowed to decide ANYTHING for myself. Always you. Or Dad. Or some other fucking stupid bastard!” Jenny breathes excitedly into the phone, seething. He has never heard her say fucking before. Now her mouth is close to the receiver, her voice dark and husky, thrusting the words: “They have ta-ken the tele-vis-ion, Tho-mas.”

Maloney enters the office. He glances curiously at Thomas. Thomas writes “Jenny, hysterical” on a slip of paper.

“I’m hanging up now. Bye, Jenny. Bye.” He hangs up.

“I need to pick her up,” Thomas grumbles. “I don’t know if I’ll be back today.”

He gets to his feet, snatches up his briefcase, and removes his coat from the hallway closet. Then he rushes through the store without saying goodbye to anyone, despite the inquisitive look Annie gives him. The glass door glides closed behind him. He lights a cigarette, hails a cab. Before the cab arrives, he gets Jenny on the phone again. Howling now and incoherent.

The last time he saw the apartment was many years ago. It’s in a narrow, indistinct redbrick structure squeezed between two taller buildings, the tallest of which is now apparently equipped with balconies. Small trees have been newly planted on each side of the street. A woman carrying a child strapped to her chest leaves the playground across the way. The playground is also new. A fire station used to be there. He remembers the constant howling of the sirens when he was very little. Then it’d been razed, leaving an empty space where local kids hung out in great, squealing flocks, and where he and his friends built a fort made of boards (and one summer, in this fort, they’d smoked their first cigarettes, which they took turns stealing from their fathers). But the building looks the same. The windows haven’t been replaced. There’s no intercom. Even the door with its chipped blue paint is the same. Thomas shoves it open with his foot and steps into the stairwell. A steep stairwell adorned with something that was once a wine-red runner—now so filthy it’s nearly black. The wood creaks under him, the timer light clicks off. He locates the light switch and continues up to the fourth floor accompanied by the ticking of the timer light. As children, he and Jenny couldn’t reach the switch, so they had to feel their way forward in the darkness. He puts his hand on the railing. The hand recognizes each turn, each crack, each unevenness. The pungent odor of rot and mothballs is so familiar that he doesn’t even notice it at first. But suddenly it nauseates him. His father’s apartment door is open.

Jenny’s sitting in the dark on the edge of their father’s unmade bed, staring at the wall. The curtains are closed. The floor is strewn with papers, clothes, overturned lamps, and shards of glass. The air is thick with dust. A dresser has been knocked over, and the arm of a shirt sticks out from one of its drawers. Thomas enters the living room. There’s more light here. The television is missing, and so is their father’s record collection. The coffee table is also gone, as well as the silverware—the hutch is open. A dish with a flower motif, which belonged to their grandmother, has fallen to the floor and cracked down the middle. An apple core lies beside it. He goes back to the hallway and closes the front door. The nasty odor of decay wafts from the little kitchen. The apartment has been empty for probably a month and a half. Jenny stopped by only once after their father was arrested, to water the plants. But someone else has clearly been here. Thomas goes to Jenny in the bedroom. She’s still sitting on the bed, now with their father’s pillow in her lap. He squats before her. “Come. Stand up. I’m taking you home.” “Someone broke the lock,” she whispers, running the back of her hand across her mouth.

“It doesn’t matter, Jenny. Stand up.” He takes hold of her hand and tugs on it. But Jenny won’t stand.

“What have they taken?” she asks.

“I have no idea. There’s nothing here.”

“The coffee table and the television,” Jenny whispers.

He clutches her arms and hoists her forcefully to her feet. “We’re going now. C’mon.” She sniffles. Leans heavily against him. He wraps his arms around her, embraces her. She smells of warm, spicy perfume and nervous sweat.

“Don’t be afraid. There’s nothing to be afraid of. It’s over. He’s dead, it’s all over. We don’t need to worry about anything.”

“Oh,” she moans, “oh, oh, oh. I’m so tired. I’m so tired.” Thomas guides Jenny through the living room, where several wilted cacti with long, gnarled limbs are collecting dust on the windowsill. Now he notices an armchair lying on its side. It’s been slashed, and he can see the gray lining inside. In the stacks of paper on the floor is a photograph of their mother. “The toaster,” Jenny says, tottering out to the hallway. He picks up the photograph and puts it in his pocket. Jenny’s already in the kitchen. He follows her. A swarm of tiny flies buzz lethargically in the sink. The smell is unbearable. Something indefinable and gelatinous has formed a green stain on the kitchen table. Jenny braces the toaster under her arm and gets to her feet. She stares at the floor as though turned to stone. Thomas shakes his head. “No. Don’t do that. C’mon,” he says, brusquely. “You’re coming with me.” And she actually follows him, but when they reach the hallway, she pauses again and slides her hand along the dark brown wall. “See,” she says. “Here it is.” She takes his hand and guides it across the cracked paint, and he can feel the inscription that Jenny etched into the wall the evening he’d gone to the emergency room. Thomas is stupid. She laughs suddenly and loudly. Then she slides to the floor with a thump and begins to sob. He doesn’t have the energy to console her. He leaves her there and returns to the bedroom, where the smell is less offensive. He rights the overturned dresser and opens the drawer, the one with the shirtsleeve poking out. Inside he finds their father’s threadbare sweaters, his socks bundled in pairs, and a few pairs of underwear. The air is thick with dust and stale, stuffy heat, combined with the stink from the kitchen, sour and abominable. He checks the other bedroom, still furnished with bunk beds plastered in stickers, the ones they’d slept in as kids and also when they were older, when he was much too tall to sleep in it and had to curl into a fetal position. Standing stock-still, he regards the fading green wallpaper and its minute white vines. All the sleepless nights he laid waiting for their father to come home. Jenny’s uneasy sleep, her getting up and pawing around on the floor looking for her pacifier whenever she’d dropped it. Her whimpering. And then the relief he felt when he finally heard the key in the door, and Jacques’s heavy footfalls crossing the wooden floorboards, on the way to the kitchen for a beer. This was followed by the smell of cigarette smoke billowing through the apartment. He can almost smell it now, can almost hear their father rummaging in the living room. Then he’s overcome with dizziness. He staggers across the room and parks himself on the lower bunk, dropping his head between his knees. “What are you doing?” Jenny stands in the doorway, her raised eyes moist with tears. After a moment she sits beside him. The thin, stained mattress slumps under her weight. She begins to hum. Then she says, “Look, my little goldheart!” She sounds like a five year old. She runs her index finger over the sticker. “And the angel and the purple smiley face Aunt Kristin gave me . . .” Something seems to move at the outer edge of his vision, but when he turns his head there’s nothing. He stands. “Let’s go,” he says, panic-stricken, grabbing Jenny and towing her along, but she won’t come with him, she wants to return to the bunk bed. She says, “Stop it, Thomas,” and goes limp, holding onto first the bedpost and then the doorjamb. But he tugs, pulling her all the way into the hallway. Just as she’s about to stumble over the doorstep, he punches the door and kicks it. “Fucking hell,” he shouts, “Fucking piece of fucking shit!” He kicks at the door again. “Piece of shit!” Kicking harder, the wood snapping. He yells, “I hate this shitassfucking place!” He’s hot now, he wants to set fire to the entire building, he wants to choke the life out of Jenny; he kicks the door again, buckling the frame, anger thundering through him.

“Thomas,” Jenny whispers.

“FUCK!” Thomas roars. The neighbor’s door opens and an old woman sticks her head out. “I’m calling the police!” she cries in a shrill, thin voice. Jenny steps toward her. “But it’s just us, Mrs. Krantz. Thomas and Jenny, Jacques’s children, you remember us, don’t you?” Thomas balls his fists and breathes heavily, clenching his teeth. Mrs. Krantz hesitates.

“You scared me.”

“Jacques is dead,” Jenny says.

“Jacques is dead? Jacques O’Mally?”

Thomas starts down the stairs. He hears Jenny speaking in a low voice, suddenly clear and normal, almost ingratiating. “Mrs. Krantz, have you heard any strange sounds coming from the apartment recently? It looks like it’s been burgled. Have you heard anything suspicious?”

“Burglars?” Mrs. Krantz stutters nervously. Jenny continues, “Yes, it’s awful. Have you heard anything? Can you remember seeing or hearing anything?” Thomas can’t stand Jenny constantly repeating herself. Mrs. Krantz, he notices, has come all the way out into the hallway. She’s wearing a hairnet over her wispy, curly hair.

“Have you heard anything coming from my father’s apartment?”

“I don’t hear so well,” Mrs. Krantz says, tugging on her long earlobes. “Everything gets worse over time, everything, everything. It’s hopeless . . .” She squints and points down the stairs at Thomas. “Is that your brother? I remember him.”

“But you haven’t heard anything?”

Mrs. Krantz shakes her head. Thomas’s legs itch. If Jenny says “have you heard anything” one more time he’ll scream. Then he’ll murder her.

“We need to go right now, we have things to do,” he says curtly. “C’mon, Jenny.”

“It was so nice to see you again,” Jenny says, offering her hand to the old woman.

At last Jenny totters down the stairs, the toaster under her arm. Mrs. Krantz waves her bony gray hand, and Jenny waves back. Thomas is already outside in the sunlight, his cigarette lit. His pulse gallops. A thin layer of cold sweat covers his back and belly. Instantly he’s drained. The sun hammers down through a blue sky, blinding them; they sit side by side on the stoop, overwhelmed by discouragement and exhaustion. Jenny steals the cigarette from Thomas and takes a deep drag. “You don’t smoke,” he says, grabbing it back. “Can you believe Mrs. Krantz is still alive?” Jenny says. “She was such a loathsome bitch, a mean, nasty, wicked bitch. Remember that time she claimed we’d tortured her ugly mutt?” Thomas nods, but Jenny continues, agitated. “Just because we were friendly enough to walk the dog when she was sick!”

“I remember, Jenny.”

“Remember how he beat us that night? And now here she is, being all nice to us. The loathsome bitch! I should have punched that pig right in her face.” Thomas looks at Jenny. She looks angry. Then comes a faint smile and a moment’s life in her green eyes. He smiles tiredly. She squeezes his arm. A bus drives past, spraying them with dirty gutter water, but they remain seated. The afternoon sun is getting lower. For some time, they are quiet. School’s out and kids are scurrying cheerfully down the street. The boys tease the girls, the girls tease the boys. Bodies hopping and dancing and running and jabbing and slapping and pinching and gesticulating. A red-haired girl leaps onto the back of a skinny boy. Thomas suddenly feels rinsed and cleansed by the loud and happy cries of laughter from the herd. Then he remembers they’re not allowed to be here. They don’t have access to the estate. When he stands, his left foot’s asleep and his knees are stiff. Only now does he notice how cold the air is. “Don’t tell anyone we were here,” he says, squeezing Jenny’s arm.

He walks with Jenny to the station and takes the bus back to the store. It’s almost completely dark now. Maloney’s done with the accounting. The shipment arrived today after all, and now it’s in place. The chandelier’s yellow light makes the store seem smaller and cozier. Annie’s on her knees sorting something in a cabinet, Peter’s leaning against the ladder blowing an enormous bubble with his chewing gum, then it pops in his face. He seems more stooped than usual. Thomas drops into a chair in the office, sighing. “Have a pastry,” Maloney says. He’s sitting with his legs propped up on the table and riffling through a catalog. He pushes a plate filled with cream cakes toward Thomas. Thomas pokes at a strawberry with his teaspoon, then sets the spoon down. “Someone was in the apartment. Everything was ransacked.”

Maloney peers up from his catalog. “Junkies?”

“Maybe.”

“Maybe it was a while ago.”

“But it looked recent.”

“How could you tell?” Maloney sets his feet on the floor and inches closer. His gut bumps against the edge of the table.

“There was an apple core on the floor. It wasn’t dried up, it was fresh. Only a tiny bit of brown.”

Maloney leans all the way back in the boss’s chair: one long, fluid motion. “You sound like an amateur detective. Some kid could’ve tossed an apple core there, especially in that neighborhood. Don’t you think you should close the book on your father’s story?” A strip of Maloney’s stomach is visible between the elastic of his pants and his shirt, which has slid up.

“He never did a goddamn thing for you while he was alive, and I’m sure it’ll be the same now that he’s dead. You look like someone who needs a drink. We can ask Annie to lock up.”

They sit at the bar. The bar wraps around them in a very safe and inviting way. Thomas is on his second martini, while Maloney slurps the last of a piña colada. The girl behind the bar smiles at them under sharply trimmed, bleached bangs, and the music is just their style—as if she knew precisely what they liked. And now they’re acting kind of goofy, unrestrained. Thomas has nearly forgotten about the break-in and Jenny’s naked, frightened face. His glance lingers on the girl’s eyes, which are dolled up in black. Are they blue or gray? Maloney says, “Maybe Peter’s gay.” And Thomas says he thinks Peter’s a virgin. “But the kid’s twenty-two years old, for God’s sake.” And Thomas says, “You can’t talk about anything but sex.” “What about you?” Maloney answers, and then Thomas’s cell phone rings for the third time—he’s ignored it until now; it’s Patricia. “I need to take this,” he says, pushing the door open and stepping onto the sidewalk as he grapples with his cell. Cool wind whips at his face.

Patricia’s already home, she says, it’s past 8:00, and they’d agreed to have dinner. Did he buy wine? Bread? Chicken? Vegetables? Thomas stabilizes himself against the wall with his left arm. “I’m coming,” he says. “I’m taking a taxi right now. I’ll bring Chinese. And beer. I’m sorry, hon, I lost track of time.”

“I don’t want Chinese,” Patricia says angrily, “and you sound trashed.”

Maloney isn’t at all happy that Thomas needs to go, but he doesn’t even stand up when Thomas gathers his things and pays the bill. They say their goodbyes. Maloney calls out, “See you later!” Thomas trudges up and down the street, but there’s no available cab. Through the steamy glass door he can see Maloney seated among a group of younger men and women, whom he’s already begun to entertain with wild gesticulations. Out here it’s cold as hell. Thomas heads toward the wider boulevards, buys beer and cigarettes at a deli. He’s freezing and shivering, and finally a taxi pulls along the curb. It’s a pleasant ride through the city. I love the lights and the darkness, he thinks, lights and darkness, and just like that they’re at the door of his building. It’s all too quiet here, he thinks. And I haven’t bought any dinner, I can’t go home without any dinner. Thoughts like flies and stinging insects: Where are my keys? An apple core, the stench in the kitchen. If she doesn’t want Chinese, I need to go all the way down to the tapas place, it’ll take at least fifteen minutes.

When he balances through the door with a tall stack of takeout containers resting on the palm of his right hand, he drops his key and is almost dumb enough to bend down and pick it up and thereby drop the containers with all the food, but he manages not to. His head’s buzzing. He licks his lips, a raspy dryness in his mouth. The long hallway is high-ceilinged, painted white. He hears Patricia approaching from the living room in her bare feet. She pauses a few feet away. “Sorry,” he says, forcing himself to smile. “It’s been a strange day.” She tilts her head. The light lands on the left side of her face, the high cheekbone, the ear. “I was wearing a dress, but I took it off.” She tosses her hair back, lifting her chin. “I thought we were going to have a nice evening.”

With his back he pushes the door shut, then sets the containers on the low table under the mirror.

“And we will, won’t we?”

He catches a glimpse of himself, ruddy-faced, bags under his eyes. Then he advances toward her, and reluctantly she falls into his embrace. “You smell like alcohol,” she says into his neck, “and I’m hungry.”

She’s wearing something that looks like pajamas, but he’s not certain they are pajamas. Silk that hangs loosely from her, no doubt very expensive. Patricia spends a lot of money on clothes. Patricia wants a baby. Patricia’s ambitious, but she wants a baby. She crawls onto the sofa and bites into an artichoke heart. She raises her beer to her mouth and drinks. Then, shifting herself, she points at the tapenade. She’d like some of that, too. In the blue armchair Thomas sits arching forward, longing for a cigarette. But then he’d have to go all the way down to the street, and that wouldn’t be the best thing to do right now; it’d be downright rude. He shovels some lettuce into his mouth and bites into a hunk of bread, realizing that he hasn’t eaten anything since lunch. When Patricia’s full, he eats what’s left in the containers, and when he’s emptied the containers, he leans back, lethargic and sleepy. Patricia, apparently no longer angry, asks how his visit to his father’s apartment went. He can’t muster the strength to tell her how it looked, so he tells her about Mrs. Krantz instead, trying to make it sound light and funny. “Her voice sounds like . . . like some screechy kid pissing in a potty.” Where that came from he doesn’t know, but Patricia smiles, her eyes growing friendlier. “Did she sound like the screechy kid or the piss hitting the potty?” she asks. Thomas returns the smile. Staring into each other’s eyes, they are in harmony, everything they have together is in that moment, a fraction of a second. Then Thomas glances away. “I have no interest whatsoever in going to the funeral. I’m considering not going. Why should I go? For whose sake?”

“For Jenny’s, I guess.”

He doesn’t answer that.

“Do you think your aunt and Helena will go?”

“No. But Jenny’s probably invited them. I can’t deal with Jenny either, for that matter. All of this means nothing to me, I don’t want to be involved.”

“But Thomas. Isn’t it best that we go, get it over with? At least then you’ll never regret not going.”

“But I can regret that I went,” he says, standing. The city glimmers in the darkness, under a yellow half-moon. Patricia sighs and collects the containers.

“We’ll go out afterward and have some champagne, just you and me. We’ll celebrate when it’s over,” she calls out on her way to the kitchen. Slap, slap, the soles of her bare feet against the wooden floor. Water running in the sink. She’s rinsing the plates, no doubt. Thomas opens the window and lights a cigarette. He leans across the cornice and blows smoke into the cold, damp night air.

Patricia returns to the living room. She stops, preparing to say something, but hesitates. Instead she says, “Want me to put my dress back on?”

He turns toward her, making sure the hand holding the cigarette remains outside. “You don’t need to. I’d be fine if you just took your clothes off.” She regards him solemnly. Then she smiles and begins to undress. He doesn’t have any desire for this at all, but now there’s no way back. So ridiculously compliant of him, just because he felt guilty for coming home late, for smoking indoors when he’s agreed not to, for not making dinner for her, for not talking with her. For coming home drunk like a loser. Now she’s naked and standing in the center of the room, her fair skin almost golden in the half-light of the reading lamp. He looks at her hips, her pubic hair, her smooth thighs. He looks at her belly, a little distended. Her breasts and her long arms, her slender throat. Her skin is slightly wrinkled right above her knees. Her eyes are so black. He takes a deep drag of his cigarette, then tosses it away. He thinks of Annie’s big ass and quickly begins to remove his pants—he needs to be fast now, when, miraculously, he’s erect—and soon he’s spinning Patricia around and draping her over the sofa. He gets on his knees behind her and eases into her, his eyes closed; she gives herself to him, she’s soft, he pulls her close, and just when he’s about to come everything grinds to a halt. He notices a fly on the wall and wonders what it’s doing alive this time of year, then images of his father’s apartment rush through his mind, the bunk beds, the smell, it nauseates him, he draws himself out of her, lies on his back on the floor, turns his head away when he hears Patricia sit beside him, sure that she’s either eyeing him worriedly or accusingly. Soon he hears her stand and go to the toilet. He feels his spine against the floor, the pain. He’s tall and thin and bony. His shirt curls up along the hem. He’s still wearing his socks. But a little while later, after they’ve gone to bed, she does everything she can to be good to him, patiently and expertly, so expertly that even though he doesn’t feel up to it or want to, she succeeds; she knows his body, knows precisely which stimulations arouse him, and he gives in at last. He’s relieved that it feels good to enter her. She makes faint, delicate noises, and he sees her quivering eyelids. When he finally comes, with enormous relief and oddly jarring grunts, her eyes are radiant now, her gaze fixed and sated. She removes a stray lock of hair from her mouth, tucks the duvet around him, and turns out the light. Then they fall asleep.

On Saturday morning Thomas wakes early, his heart thumping, stressed, uneasy. It’s 6:00 A.M., still dark outside. Patricia sleeps with a hand on her belly, and the bed smells like old man. He rolls over, tries to get his pulse under control. Can’t. He goes to the bathroom, drinks water. Then back to bed. Falling asleep seems impossible, yet he must’ve slept, because it’s suddenly light outside, and he’s dreamt, and now it’s 9:30. Patricia’s up, and his telephone beeps with a text message. Drunk with sleep, he reads, “you need to help me, the toaster doesn’t work, j.” For God’s sake, she’s got to stop this now. Instantly, he’s pissed. Feeling the tension in his neck, he kicks off the duvet. “stop it,” he writes. “aren’t you sweet, thanks a lot,” Jenny replies. He curses under his breath and steps into the shower. He pulls on pants and a sweater, clean socks, running shoes. In the kitchen Patricia sits swaddled in her duvet, reading the newspaper. She drinks coffee. She’s bought bread and butter at the bakery. There’s also juice. “Good morning, honey,” she says, sliding over so that he can sit on the bench. She’s done the dishes. A half-empty bottle of beer rests on the kitchen table, and she’s put the food containers in a garbage bag and swept the floor. But she didn’t use the dustpan: dust and crumbs are heaped in a little pile in the corner, near the sink. Thomas pours coffee and butters his bread. Jenny texts, “knew I could count on you.” He falls for it every time. She feigns helplessness and insinuates that he doesn’t care about her, and so he comes leaping to her aid after all, motivated by a guilt he has no reason to feel. But not this time, hell no. “fine,” he responds, skidding his cellphone across the table. “What’s going on?” Patricia asks, looking at him. “Nothing. It’s just Jenny. She’s obsessed with the stupid toaster.”

“Toaster?”

“I can’t explain it. And it’s boring! Ridiculous. She’s trying to manipulate me, as usual. I guarantee she’s bored. Alice is off with her new boyfriend all the time, she says, and Jenny just sits staring at the wall.” He hears how hotheaded he sounds, how loudly he’s talking. Already he regrets it, but he can’t help himself now.

“She’s working, though, isn’t she?”

“Yes, but when she’s not working. She works the late shift. All she does is eat, all day. And stare. That fatty.” Thomas slams his cup on the table. “I’m going for a walk.” Patricia looks at him, surprised, then returns to her newspaper with a shake of her head. He’s almost never angry. Now he’s boiling with rage. He takes the stairs down from the sixth floor, tramping hard on the steps, pounding his fist on the elevator at every level. Luckily he left his cellphone back in the kitchen, otherwise he would’ve called and given her an earful. The temperature outside is colder than yesterday, the wind’s blowing from the west. A plastic bag dances in the gusts. He should’ve worn a jacket. He fishes his cigarettes from his pocket and finally gets one lit after several attempts. Fucking wind. Maybe the door of his father’s apartment was busted a long time ago. Maybe it was just some junkies, like Maloney suggested, who’d stolen the silverware and a few pieces of furniture, or some drunken second-hand shop dealer, or some boys, or maybe all of the above in several rounds. Maybe it really was some kid throwing an apple core through the door on his way down the stairs. But it was in the living room. Thomas turns a corner and the wind lashes his face. The park on the other side of the street seems gloomy in this gray weather. An old woman with two small dogs is practically flying through the air. A band of youths hang around the benches at the park entrance. Farther down the street there’s an ambulance, and the EMTs are maneuvering a stretcher into the vehicle. His rage dissipates once he’s trudged around the block. Yet he still has no desire to go upstairs to Patricia. He decides to go grocery shopping. The supermarket is filled with families chugging around with large carts and piling them with items. There’s a line at every register. The families with children appear to be buying groceries for the entire week: milk, bread, frozen foods, cereal, huge packages of toilet paper. Thomas removes products from the shelves, but the entire time his ears ring with a high-pitched note of irritation. And when he puts his items onto the belt—goat cheese, red onions, crackers, sparkling water, and a whole bunch more—he suddenly stops. Every single one of these people will die. Every single person, no matter how old they are. The ones babbling cheerfully, clowning around, having a good time, arguing and talking, or lonely or hunted or sad or happy or relieved—even plain joyful—they will all die. Maybe soon. They’ll lie like wax figures in some morgue. Their insides and their flesh will swell and rot, bacteria will explode inside their bodies and make them stink like dead cows in 95-degree heat. He looks at a dark-skinned, middle-aged woman behind him, at the young blond man at the register, at a grandfather holding his small grandson’s hand. They’ll all be disgusting corpses. Maybe very soon. The grandfather actually looks like someone who might kick the bucket any day. The kid could run in front of a car. The woman could have a terminal illness without knowing it. Him too. Even him. Maybe he’s got cancer. He slides his card through the machine and grabs his bags. He has a headache, a hangover, and stiff legs. The glass door glides open and nudges him back onto the street with a puff of warm air. Son of a bitch. Their father lay with his eyes closed, his dark hair combed back; one of the guards had found him, dead as a doornail on the floor. Heart attack. A white sheet covered his body. When they removed it, he was wearing prison garb. “Yes, that’s him,” Jenny had said, though no one had asked them to identify the body. She took a step back and squeezed Thomas’s arm. He felt nothing but loathing. There he lay, a corpse, already pallid and stiff. He recognized with a cool indifference some of his own features: Yup, that’s how I look, too. It was as if their father resembled a boy or a young man, and yet didn’t. His features were smooth, wrinkle-free. The dome of his forehead, his jutted chin, his broad mouth, his thick lips. His face expressed nothing. It was clear that he was no longer a human being. Yet it was unmistakably him. The body, a form for the life that had been inside him, like a mold one lifts a cake out of. The cake had been eaten. Their father’s big hands were crossed over his abdomen; they’d probably struggled to set them just so, or maybe they’d hurried, as soon as he’d been declared dead by the prison doctor. With a sudden tenderness, Thomas imagined several female officers with keys and pistols in their belts standing over the deceased, washing his ears, cleaning his nails. Arranging him, getting him ready. But it was the nurses who’d fixed him up. Those hands unnerved him; they were the same ones that had filled so much of his childhood. The hands he and Jenny had kept a close watch on, the entire time, those fast, unpredictable hands. Their father wore the ring with the black square on his little finger. He’d inherited it from his big brother, who’d been in the foreign legion and died when he was twenty-six, and he’d always promised Thomas that it would be his some day. “When the time comes, you’ll get the ring, Thomas. Before my brother got it, it was my father’s. When I die, it’ll be yours. And your son will have it after you.”

“But you can’t die,” he’d said, anxious. He was seven years old.

Their father had laughed out loud. “Ha! I’m not planning on it!”

Thomas wanted nothing to do with the ring. They must’ve forgotten to remove it when they prepared his body. Jenny squeezed his arm. “He looks so different,” she whispered. She’d visited him at the prison, so she must’ve known. He hadn’t seen his father’s face in many years. Outside it was cold, but the western sky was soft pink, golden. The bushes shivered when they walked toward the road. Thomas had taken the package containing his father’s possessions from the cell; they’d just handed it to him, without asking whether he wanted it or not. He could have chucked the whole thing in the garbage can on the way home, but the package now lay at the bottom of the bedroom closet, on top of his shoes. He’d first realized he had it when he got home. Later he’d opened it and found the pathetic dirty magazines, the notebook with telephone numbers sloppily scratched in, and the watch with the worn leather strap—which the old man had owned for as long as Thomas could remember. Every time he raised his arm to smack him or Jenny, or just raised his arm threateningly, pretending he was going to hit them—which was almost worse than the punch itself—he’d seen the reflection of light on the face of the watch and tried to tell what time it was. As a way of shielding himself. Like whistling when you were being beaten. Or reciting a verse in your head when you were being yelled at by the teacher, in front of everyone. Later he sang pop songs to himself, but around his sixteenth birthday nothing worked anymore, and so he began to fight back. Though he was taller and bigger than his father by the last year he lived with him, his father was almost always superior, except the one incredible time when Thomas had managed to haul him down to the floor and sit on his chest staring directly into his eyes, hissing: You will never hit me again, you bastard. He was agitated by so many emotions that he nearly lost his breath. As well as a strong desire to cling to his father’s body, to feel his arms around him: tears, love. Their father had only smiled and shook his head, clucking his tongue. And Thomas stood and walked to his room. The next day he ran away from home.

Wind rips at the enormous white tarpaulins covering the façade of the adjacent building. He still has no desire to return to Patricia, but he can’t stay out here. A woman opens a window on the second floor. He meets her glance for a moment, then her face disappears behind a checkered cloth that she shakes out vigorously. Crumbs and fluff billow in the air like snow. He takes the elevator up and carries the grocery bags into the apartment. The bathroom door opens, and Patricia exits with a towel around her head. “I’m sorry,” he says.

“Every time you walk through that door you say ‘I’m sorry’.”

“I know,” he says.

“Did you go to the store?”

“Just picked up a few things.” He turns and grabs the bags and walks down the hall. He gives her a quick peck on the cheek as he passes by; she smells like fresh laundry, but there’s also this hint of earthiness, of wet soil, which he always finds off-putting. He sets the bags on the kitchen table and checks his cellphone. Jenny has called several times. She’s sent three text messages: “please can’t you help me?” and “I’ll take it to the shop then” and a half-hour ago: “aunt k called.” He hears Patricia setting up the ironing board in the living room. With the phone in his hand he opens the bedroom door. It’s cool and dark in here. He sits on the bed. His clock ticks faintly. He doesn’t want to call. After a short time, Jenny answers, out of breath: “What do you want?”

“What’s up with the toaster?”

“It doesn’t work.”

“Why are you obsessed with it? Why do you want that old piece of shit? Why are you harassing me?”

“Am I harassing YOU? I think you’re harassing me. Why won’t you help me?”

“Don’t waste your money taking it to the shop, that’s crazy. Don’t waste your money on him.”

“He’s dead. It’s my toaster now.”

“Don’t you hear how ridiculous that sounds, Jenny?”

“Should I hang up now? Stop it, Alice, I’m on the phone!”

“What’s she doing?”

“Badgering me for money. Won’t you just look at it?”

“Only if you tell me why you’re so obsessed with it. Why didn’t you take a painting instead? Or Grandma’s dishes?”

Patricia stands in the doorway, a stack of creased shirts over her arm, and looks at him sharply. Then she leaves.

“Because,” Jenny sighs, her voice softening. “That is, because, you know, it meant a lot to me when I was a child. When we made toast. We lived on bread, Thomas. It was magical to me, it could make plain things interesting. Toasted bread was fragrant and tasty, especially if we had butter or jam. I know it’s nostalgic. But it’s a good memory. For me, at least.”

Now it’s Thomas who sighs. “A good memory. Do you really mean that?”

“Yes.” Long silence. “I’d like to hold onto that good memory.”

“It sounds like you’ve taken a course on positive thinking.”

“I haven’t. I’m just thinking that I might as well make the best out of it.”

“Out of what?”

“Well—I don’t know. Everything.” They fall silent. He hears Alice clattering in the background, and a television. Jenny clears her throat.

“Okay,” he says. “I’ll look at it. Will you be home in an hour and a half?”

“I’m always home, Thomas.”

They hang up, and he sits staring at his shoes. Then he stands and walks back to the kitchen. While he puts his groceries in the fridge, Patricia comes in. She says, “You seem very strange.”

“What makes you say that?”

“Because that’s what I think.”

“Are you trying to start a fight?”

“No.”

“Have I done something wrong?”

“No. But you seem strange.”

“Oh, Patricia. Stop. I’m just not quite myself.”

“How so?”

“Restless. Odd.”

“What do you mean ‘odd’?”

“Claustrophobic.”

“Claustrophobic? Do you want to talk about it?”

He looks out the window. “I’m going over to Jenny’s soon. I promised I’d help her with something.”

“I’m going with you.”

“You don’t have to do that. I won’t be long. We can see a film later.”

“Don’t you want me to come with you?”

“That’s not what I meant.”

“Well, then I’m coming with you.” Patricia gives him a look, challenging him to tell her she can’t come. Her eyes bore into his. “It’s been a long time since I saw Jenny and Alice.” Thomas glances at the floor. And so Patricia gives up her ironing and goes with him. The sky’s blue, and the green river water reflects the treetops and the silhouettes of houses. The train screeches slowly southward, out toward the suburbs that form a broad and frayed ring around the city: public housing high-rises and wide swaths of rundown row houses, body shops, storage sheds. Huge factories surrounded by barbed-wire fence, smaller industrial plants. A junkyard here, a warehouse with a big wind-swept parking lot there, a lumberyard, then more of the tall cement towers where people are crammed together beneath ceilings thick with asbestos, the best of which have access to a boxlike balcony. Though she’s now on a sugar-free diet, Patricia has bought an apple pie. She squeezes his hand. They walk through the streets where young men hang out in front of delis and fast food joints. A whiff of beer and smoke wafts from the bars; they pass the shopping plaza with the movie theater, where people stand in line at the ticket window. A gaggle of women scowl at Patricia when she stops to pick up her silk scarf. The elevator rocks threateningly. It snails its way up to the eighth floor. It smells of piss here. They look at each other the entire way up, but say nothing. Alice opens the door. She seems surprised. “Look who’s here!” But she gives Patricia a hug and lets them enter. For a moment Thomas thinks: She looks like Mom. But that’s probably just his imagination. Alice is small and slender and has a prominent nose and a pretty, curvy Cupid’s bow like her father. Her golden-brown skin is smooth and fine, her dark eyes almond-shaped and a little crooked. She’s shaved her head. A snake tattoo threads its way up over her neck to the back of her head. She’s only just turned eighteen. Dropped out of school, unemployed. For a moment, Thomas recalls her sitting on his lap when she was little. The way she’d held onto his neck when he carried her. Now she steps to the side so he can enter the apartment. And here comes Jenny, smiling, from the kitchen; she looks hot and sweaty, her lipstick seeping into the small wrinkles near her mouth. She sees Patricia and says: “You’re here?” Patricia smiles and hands her the pie. The kitchen is a mess, and a large pot simmers on the stove. “How nice. I was just making some soup.” Jenny washes her hands. “I thought Thomas might want some lunch, but maybe you’ve already eaten?” Thomas leans against the fridge. One can see a long way from the kitchen window: the forest in the distance, high-rises, other parts of the city. When he leans forward and glances down at the area between the buildings, his stomach lurches: networks of trails, a playground, parked cars. A few children run across one of the fields wielding a kite on a string. It swirls in the air and flutters back and forth in the wind, and it looks as though they can barely hold onto it. He turns. The soup is sludgy and gray, and smells nauseatingly of cabbage and pork fat. Patricia converses politely, Thomas watches a flock of geese. Or are they ducks? He goes to the living room, where the curtains are drawn. Darkness, low furniture, a whole lot of embroidered pillows on the sofa. On the wall a number of faded drawings from when Alice was a kid, signed with large, clumsy letters. For the world’s best mom. Congratulations Mom. A reproduction of a picture of a deer standing beside a lake. A framed photograph of himself and Jenny. In it, they are young and standing under a tall tree. Jenny’s skinny. She’s wearing a white dress and her thick reddish-blonde hair spills to her waist. He just looks like an overgrown boy. They hug each other, smiling. Their feet are bare. Maloney was the one who’d taken the photograph. Light flickers between the green leaves. A walk in the woods. A very long time ago. It smells stuffy in the apartment, and he wants to open a window, but marches down the hallway toward the bedrooms instead. The shelving units have seen better days. A bunch of bric-a-brac, some books, washed-out bed linens and towels in untidy stacks. A door is ajar. Alice is lying on her bed with a man. Thomas hurries back to the kitchen. Jenny has ladled up the soup, there’s no way out of it now. “Alice and Ernesto! Lunch!” Jenny shouts. “Is that her boyfriend?” Patricia whispers. Jenny nods, and rolls her eyes and shakes her head resignedly. They sit around the little camping table. Jenny passes out pink napkins adorned with teddy bears. Thomas grinds peppercorns over his bowl. Unidentifiable chunks of fatty gray meat bob around in the murky liquid. He lifts a piece of overcooked cabbage with his spoon and lets it fall back into the soup. What is she thinking, serving such dog food. She knows that he—that he can’t. That he has better taste than this. That this is . . . The kids drift in. This Ernesto is only a head taller than Alice, but he’s broad and muscular. His hair is short, black, and shiny. He greets them politely, introduces himself. He must be older than Alice, Thomas thinks, feeling discomfort, both at the soup—which actually tastes like food served at an institution—and Ernesto’s hairy hands, one firmly planted on Alice’s thigh as he shovels soup into his mouth with the other. Alice stirs her spoon around her bowl and picks at a piece of bread. “How are you doing?” Patricia tries. “It’s been so long since I’ve seen you.” “Really good,” Alice says. “Are you still looking for work?” Alice nods disinterestedly. “No, you’re not,” Jenny says. Ernesto glances up. Alert. Solid jawline. “And how about you?” Patricia regards him with interest. “Are you a student? Are you in college?” All of a sudden she sounds rather strident. He smiles curtly. “Hardly,” he says in a calm, friendly voice. “I’m a musician.” “Really, how exciting—are you a singer?” He shakes his head. “Drummer.” So that’s why he’s so muscular, Thomas thinks, clearing his throat. “Ernesto plays in a really cool band,” Alice explains, pushing her bowl aside. “They’re super awesome. You can listen to them online, if you want. They’re called El Pozo.” She stands. “They just sit around, doing nothing at all,” grumbles Jenny. “You don’t do a thing. I don’t know how you can stand it.”

“Thanks for lunch,” Alice says.

“There’s an apple pie,” Patricia says. “If you’d like to eat some later?”

Alice vanishes into the hallway. She’s in an awful rush. Ernesto turns in the doorway and, smiling, reveals a relatively nice set of teeth. There’s a noticeable gap between the front two. “Thanks for lunch, Mother Jenny.” Then he’s gone. Jenny and Thomas exchange glances. “Mother Jenny?” he says softly. “What the hell does he mean by that?”

“I have no idea,” Jenny says, ladling more soup into her bowl.

“Doesn’t he have a mother?”

“I don’t know.”

“He seems sweet,” Patricia says, raising a yellow-brown drinking glass to her mouth.

“He’s not. He’s a snake.”

Patricia swallows, then puts down her glass. “Why a snake?”

“I can just tell. He’s lazy and slimy. They just lie in bed all day fooling around. Alice is being dragged down to his level. Into the mud. Before him it was another guy. He was actually worse. An arrogant bastard, to put it mildly. She’s got a new boyfriend all the time.”

“I can find out if we have a job for her at the museum.”

“If she’s even able to handle a job,” Jenny says bitterly, putting her spoon down. “I honestly don’t know what I should do with her. She hates me.”

“Oh, stop, Jenny. She doesn’t hate you,” Thomas says. He’s irritated, dark waves in his belly. “She’s only eighteen.”

“But where does he live, this Ernesto? Here?” Patricia asks.

Jenny gets to her feet and rinses the bowls. “It seems that way, doesn’t it?” Patricia wraps a lock of her hair between her fingers; no one says a word. Patricia glances curiously at Thomas, but what does it mean? He needs to smoke, he can’t breathe, he has to leave. “The toaster,” Jenny says coolly, “it’s over there.” She nods in the direction of the big closet at the end of the kitchen table. “Can you please look at it now?”

Thomas fiddles with a little fucking screwdriver. The women are seated in the living room drinking tea and eating apple pie. As far as he can see, Jenny’s drawn the curtains—which is better than nothing. The door’s ajar, but he can’t hear what they’re saying. Are they laughing? Yes, Jenny is, and now Patricia too. The toilet flushes. Heavy steps in the hall, it must be Ernesto. The toaster is unbelievably greasy and revolting and littered with old crumbs. That he’s really sitting here prying it apart in this kitchen fills him with disgust—that he’s agreed to do it. Insanity. That old feeling of deep-seated anger at Jenny and all the guilt that comes with it hits him like a slap. It’s so incompatible. The sobbing. There’s no development in our relationship at all, he thinks. It’s as if her entire personality exists to play the role of victim, huge and hollow, for my benefit only. So I can fill the holes with my shame, my strange, indebted need to protect. The screwdriver slides from his hand, he’s warping the screws. He props the toaster between his knees, braces it tight, and tries again. It’s big and clumsy, probably at least as old as he is. He has no idea how you pry such a thing apart, he just keeps unscrewing the screws and removing all the parts that come loose, when the screws no longer hold them together. Suddenly it breaks in two. The shell of thick plastic falls apart. Thomas gawks at the guts of the toaster. And all at once he jerks his head back.

Fastened between the now detached outer shell and the heating coils, on either side, is a thick packet wrapped in tinfoil and taped carefully together with clear, yellowed tape. At first he simply stares. Then he manages to pry them out. He hears Patricia’s voice approaching. Feverishly he stuffs the two packets under his shirt, then under the waistband of his pants. When she steps into the kitchen, he’s back to sitting over his work, replacing the screws in the tiny holes. And what part belonged where? He hadn’t organized the pieces in any manageable way. He’s beginning to sweat.

“Is it tricky?” she asks, filling the pot with water.

“Nah,” he says. “Not really.”

Patricia sets the pot on the stove and turns on the gas jet. “Tell me when it’s boiling, okay?” Then she leaves again.