Читать книгу Only the Women Are Burning - Nancy Burke - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

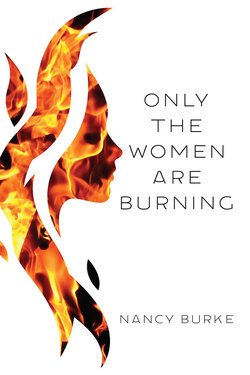

Оглавление“Affection is a coal that must be cooled; Else, suffered, it will set the heart on fire.” - William Shakespeare

Chapter 4

And there he is, the engine dying in the driveway, the screen door slapping, and his steps on the porch announcing the end of his week. He is home and the sun is still up and it is Friday and there is a weekend ahead for togetherness and I feel my energy create a smile and I can feel a brightness shining in me. He drops his briefcase, his hair is curly and in disarray as is his loosened tie over his Oxford shirt. He sees the girls at the table, goes to them, and drops quick pecks of kisses onto their lowered heads. They turn for kisses, real ones, and he bends to accept theirs on his shadowy cheek with the prickles and they return to their work. My hands are wet from cooking chicken and I move to the sink to wash them. He doesn’t wait for me to finish and turn for a hug, but he pecks a kiss on my lips, quick, dry, prickly and moves away. I am too late for an embrace.

He says, “Have I got time for a few miles before dinner?” He doesn’t wait for an answer but disappears up the hall toward the stairs.

“Did you see that I called?”

“Yes,” he said.

“Do you want to know why?”

“I want to go for my run,” he says.

I follow him upstairs. He is out of his business clothes. They are flat out on the bed and his running shorts are in his hand. His abdominals are lean and hard. So are his thighs and the dense hair on his chest is speckled with gray.

“Where is Lila?” he asks.

“Darkroom,” I say. “I need a hug.”

He lifts a tee shirt from the bed and grabs the lower hem in his teeth while his hands reach inside to the sleeves and he slides into it. He says, “I’ve had a tough day too.”

“I need to tell you,” I say.

He pauses. He sits to slip on his shoes and his eyes are on his laces.

“Cindy is dead,” I say.

“Cindy? Your old friend Cindy?” He looks up. “I’m so sorry.”

“And I watched a woman burn to death on the train station platform this morning,” I said. “She died. Cindy died in a fire. Three women died today in Hillston in fires.”

“That must have been awful. I’m sorry.” He stands up. He comes to me and puts his arms around me. He kisses my cheek. He releases me before I can lift my arms to encircle him. He is out the bedroom door.

I call after him. “Pete, it was just like Banhi.”

He returns. “Cassie, the Bangalore police said Banhi ran away.”

“And Rehani said she set herself on fire. And the women all around that shack, we know they turned their backs. But I know better. I saw her arm with the earlier burn. I saw her in flames in that shack.”

“I thought we left this in Bangalore…in the past.”

“But a woman burned today right before my eyes. Two more women too. Cindy was one of them.” I lifted my hands flat, palms up, then clasped them together. “I tried to extinguish the flame. This time I had a chance to save her. But it didn’t work.”

“What do you want me to say?” he said.

“Say you believe me. You never said that about Banhi.”

“There was no body Cassie. When the police got there, there was no body. There were no burn marks in that kitchen.”

“I saw her. Somehow, they moved Banhi, hid her body, cleaned up. When I got back with the police, it was as though nothing happened.”

“And her husband said she must have run away,” Pete said.

“And you believed him and not me, Pete. How do you think that makes me feel?”

“Did this morning really happen?” Pete asked. “Or are you having problems again?”

“Didn’t you see the news vans outside?”

He went to the window. I followed. The street was now empty of vans. “They were all over the street earlier. It is on CNN. It is on the radio news. It’s real, Pete. Don’t you dare make insinuations about whether it’s real or not. You’re my husband.”

“I think it flashed across the screen at the airport,” he said, “now that I think about it.” He sat on the floor and extended his legs to stretch. “They didn’t say the women’s names. I thought maybe it was a stunt, you know, like the women in China a few years ago. That was a cult, wasn’t it? Falun Gong or something?”

“A stunt? That’s an awful way to characterize it.”

“Women trying to draw attention to something…a cause or something.”

“I still don’t think we should call it a stunt.”

“What are you trying to say?”

“I’m trying to tell you that I was there. She was right behind me as I was stepping onto the train…and it’s scary…I’m upset…I need some time to talk about it. She caught fire and died. I just need you here. I’m terrified it can happen to me…to Lila…to anybody. Can you stay please?”

He leaned back on his elbows and stared up at me. “It must have been terrifying. I can’t imagine.”

“I think I fainted after it was over.”

“Wow.”

“The EMT’s gave me oxygen. There was nothing left of her to help.”

“Cassie, I’m sorry. I’m sorry you were there. Maybe take some time off from that job. Maybe that would help?”

“I called out today. I spent the day at home watching the news and waiting for Doug to come.”

“Doug?”

“The reporter.”

“Did you call the paper?”

“No, he called me.”

“What did the police say? What did the fire department say? I’m sure you called them. I’m sure they were at the scene.”

“I called 911. By the time they got there, the fire was done. She was dead.”

“This does sound very familiar.”

“The conductor and I tried to save her. He grabbed the fire extinguisher, but he didn’t know how to use it.”

“And you did.” He leaned forward and hugged his knees.

“Yes.” My inner glow of pride that at least I’d tried faded under his scrutiny. “You can read the news tomorrow. The reporter got here later, after he…”.”

“Here?”

“Yes, he called. Then, the other fires happened. And he didn’t come right away, but he came later. Lila brought home a notice from school that it happened to someone’s mother. Turned out it was Brandon’s mother. Cindy. My Cindy. Doug told me on the phone.”

“Doug? You sound like you and he know each other well.”

I ignored that. “The reporter…when he called back because he was late... told me it was Cindy.” I realized I was back in Bangalore in my mind. I heard myself pleading with him to believe me like I pleaded with the police back then.

“This feels like a horror movie.”

“It feels very much like…”

He stood up. “We promised that, when we came here, you would not talk about that.”

“I know…but…”

“Do you want our marriage to fall apart like it almost did back then?”

“No, of course not.”

“Then let the police and fire department deal with this, okay? I don’t want you to start butting in with their work.”

“But Pete…we’re in Hillston. There is no cultural context for women to set themselves on fire here, unless it’s some sort of protest…not a stunt. I thought it could be that, a protest, then I heard about Cindy and I knew it was something else. She would never kill herself.”

“So then it is someone murdering them?”

“Nobody knows anything. Nobody has any conclusive proof of what and how this happened.”

“It’s going to turn out to be some kind of serial killer. Remember that sniper in the D.C. area? He was a sharp shooter from the Special Forces, picking off people from nearly a mile away. They figured it out.”

“Nobody can set somebody on fire from a mile away. That was a gun, this is burning to death.”

“Watch. The police will investigate. There will be some connection between the three of them.”

“Well, maybe. If they do, at least it won’t feel like we’re all in danger, like the mayor said.”

He kissed me on the cheek. “I’m going for my run,” he said. “Let’s just have a peaceful family dinner with the kids.”

“You can’t skip your run for once?”

“What do you want me to do?”

“Help with dinner.”

“You know I’m useless in the kitchen.” At the door he turned back. “You see Dr. Gimpel lately? Maybe you need to talk to her about this. She helped a lot remember?” And he was gone.

Ages ago, Dr. Gimpel had showed me the newsreel I played and replayed in my life whenever I retreated emotionally, whenever I felt someone had failed me or I was on the verge of failing, and now, it whirled like an old 8 mm film in my head. I lay down again in my unmade bed and closed my eyes fighting my memory and my grief.

I had seen Dr. Gimpel weekly for that period after our return from Bangalore. She urged me toward yoga and meditation and my yoga teacher taught me to deepen my focus on the present, to look ahead, not behind, to ease the horror of the memory of watching Banhi die, to live as if each new day was my first. “The best path toward healing is to reach out and help others,” said my teacher. And this started my sisterhood, first with Cindy Barrow, then a collection of new mothers, at home raising children after leaving careers. She and I had grown that group to fifty moms. NPR heard of us and featured us on “All Things Considered”. Women and choices.

How much, I realized, now that she was not here, I’d always imagined Cindy and I would reconcile. I had not had the courage to attempt that reconciliation and now I would never have the chance.

I stared at the ceiling, listening as Pete stepped down the stairs, and felt a familiar hollow in my heart chakra. I flashed to Rehani’s reaction to Banhi’s burning. She was there in the kitchen. She watched as her daughter-in-law burned to death. And what loomed large in the present was Pete’s reluctance to believe me right now which felt as dishonest as Rehani’s response to Banhi’s fate. That frightened me as much as the flame had and as much as the prospect of it happening to me did too.

I got up and went to the kitchen. My husband had tried to help. He had put the chicken in the sauce and stirred it, but he had neglected to light the flame under it. I turned the knob to light the stove. The gas didn’t ignite. I did it again. Again, the scent of gas filled my nostrils. I shut it off. I twisted the knob one more time. This time, it lit like it had earlier, flame bursting around the sauté pan, flaring up and around with a whoosh. I pulled my hands away quickly and looked at Pete who had returned. “This needs some attention.”

“That’s what happened when I tried to light it.”

I moved the pan to another burner. I showed him my arm with the singed hairs. No reaction.

“I want to grab a shower,” he said. “Can you just finish cooking? I’ll look at it later.”

Lila emerged from her basement darkroom and, with a dramatic sigh as if she hadn’t eaten in days, said, “Is dinner ready? I’m hungry.”

She sat down with her sisters and in a moment was pointing out errors in their homework which they hurriedly attacked with their erasers. Their lack of defensiveness, their complete acceptance of her help was a pleasure to see. The way sisters should be, I told myself. I turned the chicken in the masala sauce, savoring the aroma lifting from the pan, and wished I could fix some of my own past mistakes as easily as they did their math. Pete joined us at the table. The green beans were a pallid green by then, but the chicken was ready and so was the basmati rice. I moved the sauté pan to the table and sat down to eat and found myself letting out a long sigh, “Oh, can someone please grab a ladle?” Pete didn’t seem to hear me. Lila reached her long arm over to the drawer and slid the ladle out with a bit of clattering. She laid it next to the pan of chicken and said, “I hope it isn’t too spicy.”

“Please, let’s just eat,” I said. I lifted the lid and a puff of steam rose and the scent took me back to the evening when I first triumphed over this recipe with help from Banhi. I could see her hands, measuring with her fingers the spices she pinched or spooned in deliberate quantities while I furiously scrambled to write approximations in my notebook. For her, this recipe had no meat, just lentils and vegetables, and my Americanized version paled in the wake of my recollection of sitting down to her finished product with naan and chutney and basmati rice with cumin seeds and cloves. This meal was in its own condition of compromise and I felt my mood sink down and I knew I was going to sound very unpleasant if I joined in the conversation. Rarely an evening dinner at this table included Pete. I passed the plate of store-bought flatbread. I passed the green beans and I scooped into the sauté pan and served my children their portions.

I watched Pete. Here he was, the young man who stepped into my life and, well, it hadn’t started with love. It started with me shouting at him from under the sarsens at Stonehenge to please step back onto the tourist’s path, running toward him across the dig where my team was meticulously working in neatly drawn grids, roped off and numbered. Pete stood in the center of the blue stones with a camera, changing lenses, aiming at the largest lintel where the early morning sun was the most brilliant for it was nearly the spring equinox.

“I’m sorry, but you aren’t allowed in here,” I said.

“I’m a photographer,” he said.

“There are professional photographers here all the time. They know to not walk in here. Their permit gives them strict instructions. Where is yours?”

“I’ll only be a minute,” he said. “Are you American?”

“No, you will not be a minute,” I said. “Step back to the path, please.”

He might have stood his ground and given me trouble, but he yielded. Then, he aimed his lens at me and took my picture. Then, he clicked another.

“Please stop,” I said.

“Hold still,” he said. “If you are American, what are you doing here?”

“Stop,” I said, lifting my hands to my face. “I’m a graduate student. Archaeology. Please.” I pulled the hood of my sweatshirt up to hide under.

“Have you found anything?” he asked.

“We’re not looking for artifacts,” I said. “They’ve all been dug up long ago.”

“So what are you doing?”

“Research.”

“Well I hope so.”

“Please, I’ve got to get back to work. Stay on the path.”

“Yes, Miss Keeper of the Stones.”

I looked directly into his eyes. “Someone has to be.”

“Would you mind if I looked at what you’re doing over there?”

“There really isn’t much to see and we’re very busy.”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I had no idea there would still be work here.”

“Apology accepted.” I returned to my work. I sensed his shadow moving off to where he should have been and I felt pleased and a bit relieved this had not turned contentious. This was not the end, however. We met later at the Peach and Thistle where he’d gone to wait for the local photo lab to develop his film. Phoebe, my roommate and assistant at the dig, studied him across the bar and turned to me. “He’s not stopped watching you.”

“Who?”

“Oh, right,” she said. “Don’t lie. You’re watching him too. Your American.”

Pete stood and Phoebe squeezed my leg. “He’s making the first move.”

But she was wrong. He left his empty glass and some money on the bar and walked out.

“Lost your chance,” Phoebe said. “Really, Cassandra, I will have to teach you to flirt.”

“I’m not looking for a man,” I said. “I’m here to study.”

“Right,” she said. “You couldn’t possibly do both, could you?”

But he returned and approached, offering me an envelope of prints. “These might just be something you’d be interested in,” he said. The enlargements of those photos of the sun coming up over the largest of the stones still hang in our hallway.

Pete’s laugh brought me back to the present. Yes, this was a family meal, suddenly bathing me in a glow of bonds and attachments. These are things that keep us whole. I let this well up from inside. Sometimes, life forces us to remain only in the present and lately it had been just that. But, when I was only in the present, I felt invisible. That part of me for which this life gave no opportunity for expression seethed. I knew I must fight to stop it from ruining this family dinner. Pete was always gone, always pre-occupied with business, always leaving me alone here. His photography was a hobby he indulged in England back then, back when I fell in love. He had been on sabbatical from his business development job at ISK, a high tech firm, which he still holds, now a sales vice president. He rarely has time to photograph us anymore much less be with us. Just this dinner, this simple Friday night of togetherness, even after my impatience with him and his required run, was the all-important present. But it felt off. It felt like Pete had pasted himself on the veneer of this family. I didn’t feel the connecting tissue.

Pete was suggesting that Lila redo some photographs with a new roll of film. I hadn’t heard all of what they’d just discussed, off as I had been on my daydream. She and Pete shared the photography hobby, not me, but I made a mental note to add film to my shopping list. She wouldn’t use the digital camera. She said film was more artistic.

After dinner, while Pete and Lila cleaned up the kitchen, the idea of a walk beckoned me, but at the front door I paused. The sky was nearly dark. The park was glowing from the street lamps and commercial lighting from the stores on the other side of the train tracks. A few shadowy human shapes with dogs on leashes strolled on the path. This had been a moist day, an after the rain kind of day, and the mist had descended below the tree line so that while I watched, it thickened. Soon, the lights cast shadows of trees upon the fog and they looked to me like tree shaped cutouts in the light beams. I knew that if I turned to see shadows of trees, they would not be visible in the fog behind me, but only could be seen as silhouettes if I faced the source of light. Still, the idea of shadows of trees on a wall of fog intrigued me much like impossible things intrigue visual artists or writers of science fiction.

“Mom, you’re not going out there,” Lila called from the kitchen.

“Oh, please, Lila,” Pete said. “If she wants to go out, I’m sure she’ll be fine. I just ran five miles and I didn’t burn up in flames.”

“It’s only the women burning, Dad,” Lila said.

I listened as they launched into an argument, Lila holding her own, Pete assuming an authoritarian tone, as a man who knows best. It went on and I stood at my distance and listened. My twins had retreated to the living room and a DVD played loud enough to drown their ability to hear what was being said. I felt amazingly calm and remembered I’d taken a Xanax. I’d relied on the drug once before. Maybe I needed to do yoga again. Maybe I should pay a visit to Dr. Gimpel. Pete was partially visible in the kitchen and I felt a bit of a sinking in my viscera, remembering his earlier response to my need to talk. I shouldn’t need a therapist for comfort, I thought. Then, the phone rang. Pete got to it before I did. He called to me and I lifted the cordless from its cradle in the hall and pressed the talk button.

“Hello?”

“Ms. Taylor?”

“Yes.” It was Doug’s calming voice. I felt a tightness leave my neck and shoulders at the sound. I turned to watch Pete hang up and that sense of a transfer of responsibility from Pete to Doug flashed as suddenly as lightning and was gone. Responsibility to soothe me. Only because Doug did it so easily while Pete did it hardly at all. It disturbed me. Stirred a mild irritation toward Pete. A sense that I must bring this to his attention.

“Your question,” Doug said.

“Which one?” I asked, momentarily distracted.

“Did Cindy Barrow’s clothes burn.”

“Did they?”

“No.”

I felt a long beat of silence pass and that beat was filled with acknowledgement for me. A small move toward knowing more about what just happened and it was because I’d paid attention and I’d asked.

“Well,” I said.

“So now the police are questioning if she treated her clothes with a chemical and, if she did and if the other two women did, was this some sort of planned thing.”

“You mean self-immolations,” I said.

“That’s right,” he said.

“I think that is unlikely. Only because I can’t believe Cindy would,” I said.

“And why?”

“Because I don’t believe Cindy would do that.”

“When is the last time you spoke with her?”

I thought. “Three years maybe longer.”

“A lot can change in three years.”

“What about Elizabeth Lindsay, the school principal.”

“Her clothes were unharmed too.”

“So they’re all the same.” I pulled at my hair at the nape of my neck. It was an old habit when I was stressed out. I caught myself and stopped.

“When will they test the clothing?”

“It’s being done.”

“Okay,” I said. “I wonder if the cops will close these up as suicides. I just can’t imagine the Cindy I knew turning to something like this. She was smarter than that.”

“I’m sorry, Cassandra. I’m sure this is upsetting.”

“Does the mayor still think we should stay indoors?”

“He hasn’t changed anything. He’s on a plane home.” Doug’s next breath was deep and slow and audible through the phone. He was tired. I could tell. “Heffly and Richmond are holding a press conference in a few minutes. I’ve got to go.”

“Okay,” I said. “Thank you for calling.” I hung up. That thank you felt so terribly ordinary. Now that I knew the answer to my question, I realized that the terror I’d shoved down deep into myself now rose up and through me like lava. It burned and flowed. My whole body felt hot, my hands sweating and my heart beating hard in my ribcage.

Pete could be right. It could be a cultish kind of stunt. It certainly wasn’t a mass murderer trying to burn women with some kind of device like a long-range weapon. I imagined a new kind of bullet, they already had exploding bullets. Four men had died at the hands of a gunman at our local post office sixteen years earlier and he had used the exploding kind. Could there now be incendiary bullets that ignited and burned a body from inside? That’s what she’d looked like this morning. Ann Neelam had seemed to burst into flame from her interior. Memory of how it tripped down her legs and out to her hands and fingers flooded me. I needed to stop thinking. I needed something else, something full of love and goodness to replace the fear and dread in my thoughts and heart. I joined Mia and Allie on the couch and immersed myself in their latest movie obsession, The Wizard of Oz, until the witch disappeared in a burst of flame. Once I saw that, I retreated to my bathroom, ran the faucet to fill the tub with bubbles, took off my clothes, and sank in up to my neck.

Later, Pete did his usual bedtime routine, undressing himself, brushing and flossing, and lying prone, neatly tucked under and plugged into his iPod with closed eyes, looking like a contented corpse. I arrived from Mia and Allie’s room, having recited another chapter of Peter Pan in all its beautiful prose and imagery and after delivering kisses onto two drowsy foreheads. I kept my movements quiet. I let my own shorts and tee shirt drop to the floor. I slipped into bed. Pete rolled toward me and whispered good night.

Here was my marriage.

“Pete,” my voice was soft, a whisper like the hand I was moving to him to make contact with his thigh, but he was into the music that faintly reached me in the otherwise silent night. He didn’t respond. I rolled onto my side, facing him, and lay my hand on his chest. He started, gasped, and opened his eyes.

“Ah,” he said. “What’s wrong?”

“Take off the ear plugs,” I said.

He did. He shut off the power. The small screen on the iPod went black. He didn’t move otherwise. “I was asleep,” he said.

“No,” I said. “I could tell by your breathing.”

“What?”

“Touch me,” I said.

He lifted a hand and placed it over mine.

“No,” I said, sliding my hand from under and rolling to my back. “Touch me, not my hand.”

I took his hand and pulled him so he had to turn toward me. “Here,” I said, placing his hand low on my body. He let his hand rest there. I rolled slightly and brought my lips even to his, leaned in. It was an awkward kiss, his nose bumping into mine, me turning myself to make us fit, and I felt his hand move up and around to my back at my waist. I moved my hand onto his thigh, moving toward him, then reaching back to bring his arm from around me, finding his hand, and guiding it, inviting him to my thigh, and he touched me and the jolt of it roused me to want more. I was letting the covers slide down and away from us. The room didn’t feel so dark now and my skin was white and smooth and I noticed his eyes were closed. I lay my hand on top of his, to guide his fingers deeper to the spot I wanted him to find. Close, nearly there, he stiffened his fingers and pulled away. “What are you doing?” he said. I opened my eyes and his were now staring into mine.

“I’m showing you what I want,” I said, so very quiet, almost dreamily.

“Do you have to instruct me?” He pulled his hand away, rolled his whole self away, his back facing me. I sat up, I covered myself with the sheet, stripping it away from the quilt, and sat cross-legged on the bed with my elbows on my knees and my head in my hands. What swelled up in me at that moment was humiliation. I recognized it, I hated it, and at that moment I hated Pete.

“Tell me what is wrong with me showing you what I want.”

“Maybe I don’t want to touch you where you want to be touched,” he said. “I was asleep. I had a long week on the road and I’m exhausted.”

“So you don’t want sex.”

“No.”

“Ever?”

“I didn’t say ever. Just not now. You don’t know, Cassie. You weren’t up since five a.m. like I was.”

“And this doesn’t help you relax.”

“I was relaxed. I was asleep, or nearly asleep.”

“The kids will be up in the morning with the sun.”

“We have to wait, Cass. You have to wait.”

“I am always waiting, Pete. I wait all week for you. I wait, worrying about you on the road, about plane crashes, about not seeing you. I wait for hugs and this and for some love.”

Pete rolled onto his back. “You don’t have enough to do then.”

“I am busy from 6:00 a.m. to when they shut their eyes.”

He did not respond. I filled the silence with a series of ugly conclusions my mind shouted to me. I reached to the floor for my tee shirt and shorts and pulled them on. I left him there and found my way to the living room and the couch and all the words I had imagined I would say to him were no longer necessary because I knew he would not understand with or without the words. There were tears then and a heaviness under my ribcage and an anxious and sudden wave of a physical desire to be touched the way I had gently asked him to touch me. I pulled a pillow under my head, stretched out, and found the crocheted throw folded over the back of the couch and slid it over me. And, while sleep simply could not find its way through my racing heart, fear of this huge fissure cracking the ground between us did. I lay awake. My thoughts went again to that longing for the life I had let be replaced with this one and, although I had not done so in a very long time, I prayed against what my heart was trying to show me until the pale streak of sunrise shone pink through the large windows to the east.