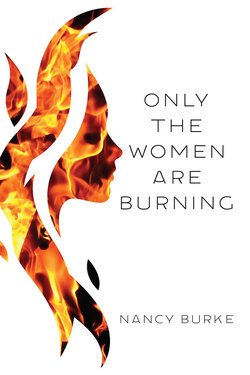

Читать книгу Only the Women Are Burning - Nancy Burke - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

December 14, Bangalore, India

That morning of rain and mud, I searched the narrow alleys of the squatter settlement, the narrow lanes, the corrugated shacks, stepping around trash and puddles of mud, carefully counting the doorways until I reached Banhi’s husband’s tiny household. There she was squatting before a large stone mortar and pestle when she shouted, “Cassandra!” After she pulled away from my embrace, she reached for Lila, who was just a year old and in a carrier on my back. That’s when I saw how drawn Banhi’s face was, her skin not glowing as it had every day, and no broad smile on her lips as before. But she tried.

“Let me take Lila, please,” she said. “Oh, she’s so beautiful. My sweet thing, say hello to Banhi.”

“Your father and mother send their love. And your brothers,” I said.

“Let’s take Lila to show Rehani. The baby will make her smile.” She turned and darted inside the small dwelling and called to her mother-in-law.

I followed her into the house. There were two rooms. The kitchen was equipped sparsely with a small wooden cabinet. Three varied sizes of pots hung from hooks over a slab of stone set back against the far wall. A shrine with Ganesh, the elephant-headed boy, and multi-armed goddess, Durga, displayed itself on the slab and before the statues were bowls of brown rice, cumin seeds and a liquid which I guessed was honey. The tiny kerosene stove, unlit and cold sat next to the door leading to a small square of muddy yard. Pads and blankets were piled in two corners of the second room and a flat carpet of faded greens and gold stretched across the cement floor which looked spotless.

I heard from the other room the unmistakable slap of hand against skin, a cry of pain, and an explosive burst in Kannada I could not understand. I was there in an instant, pulling Lila from Banhi’s arms.

Rehani’s hands kept at her work, her eyes darted from pods to bowl as tiny green peas relinquished their shells and dropped in with the rest. Her face was set in anger.

“Rehani,” I said. “If I should not have come, I am sorry. Please, it is my fault, not Banhi’s.”

“It is a day for working.”

I said, “It is my fault for coming unannounced.”

“She asked if I would like to hold the child while you two sat to visit. She is a useless bride for Harshad.”

“She looks thin,” I said. “Is she well?”

“She coughs to get sympathy.”

“Rehani,” I said. I stooped down so my eyes were level with hers. “Banhi was my aaya - I know she works very hard.”

“Working for pay spoils a wife. You have ruined her.”

I walked back to Banhi. A flushed red mark darkened her left cheek.

“Come outside,” I whispered. “Out to the front. We need to talk.”

At that, a torrent of water loud as thunder hit the tin roof.

“I will make us some tea,” Banhi said.

The rain ceased after a brief cloudburst and the quiet was welcome. Rihani had joined her and noises from the kitchen reached me from the other room, two voices, subdued. I could not make out the words, but by the tone and cadence it seemed peace had returned between Rehani and Banhi. Rehani carried a cup to me and bowed. She sat cross-legged on the small rug. Banhi carried a cup for herself and sat just a bit farther off.

They settled, Rehani leaning against a support and Lila settling into the crook of my arm. Banhi sipped from her cup, silent; the red blotch had faded to pink but there was a look of a frightened cat about her. She stood suddenly. “The stove,” she said. “I need to turn off the flame.”

Rehani said. “You will burn down the house.”

“I forget,” Banhi said.

“She does,” Rehani said. “A stove must be respected.”

Something darkened the doorway and we all looked up to see Harshad stepping into the room dripping from the rain.

“Get your husband some dry clothes,” Rehani ordered.

Harshad said, “Please, is this little Lila grown so quickly? She is a miniature of you,” he said. “Isn’t she, Mother?”

Rehani said, “And your son will be a miniature of you, Harshad, when it is time. You are making a puddle. Go change out of your wet things.”

He vanished into the kitchen and pulled the curtain across.

I wanted to turn Banhi back into the happy, exuberant girl who translated for me, who’d introduced me to the women here. The bride in red with glowing eyes at the wedding she had insisted I attend.

My year of visiting Indian homes and feeling the warmth and love among these people of the lowest caste had taught me what happiness under struggle looked like. This was not it.

“Can Banhi take a walk with me and Lila?” I said. “The rain has stopped. The sun is coming out.”

Rehani said, “She must not go out without Harshad. She is a married woman now.”

“Let me walk with you then,” he said, returning in dry clothes. “The mud is slippery.”

He walked ahead of us. Banhi linked arms with me and whispered. “Harshad wants a child. But Rehani and Jayant sleep between us.”

I said, “She hits you.”

“Just make up a story that you need me in your work for a day.”

I stopped walking. “Will she allow it?”

“She might be happy if I bring in some money.”

I thought otherwise but only asked, “What does Jayant say?”

“He says nothing.”

“What does Harshad say?”

“There is no privacy.” All this in a hurried whisper, all with a hand clutching my arm, a continual checking the distance between Harshad and us, and several furtive glances back toward the row of shacks where it was hard now to distinguish which one we had just stepped away from. Harshad turned after overhearing us.

“Banhi,” he said. “You can’t go out of the house with Cassie.”

“I live like a sister to you, Harshad. If I am to be your wife, I need to help retire the debt your father is ashamed of.”

“It won’t be like this forever, Banhi.” He glanced back toward the row where their dwelling melted anonymously into all the other tin-walled houses. “Things will change, if your father can help us again.” He turned to me. “Cassandra, can you take a message back to Kiran? The dowry money is gone. If he is prospering, he is duty bound to share that with his daughter’s family.”

“More dowry will help,” Banhi said. “But what happens when that money is gone too?” She touched the sleeve of her sari and I saw her skin was blackened, partially healed but raw and swollen around the edges of a burn with an ooze of pus near the wrist bones. Her gaze focused on Harshad’s face.

“She is awkward with the matches,” he said.

“Banhi,” I said. “Come on.”

Harshad made a move toward her. I stepped between them. “Stop!” I said. “She is coming with me.”

“Banhi is a part of my family now. I beg you not to do this.”

Harshad went to touch her and she pulled away and stepped behind me.

“You can come back if you want, but right now you are coming with me to the hospital.” I glared at Harshad. “If you love her, tell your mother she is going for medical care for her burn.” I looked hard at Banhi. “You’re going to the hospital. Tell Harshad you’ll be back when your arm is healed.”

Harshad said, “We have no money for a doctor.”

I took firmer hold of Banhi’s hand, turned and dragged her through the lane, but after a few hundred feet I let go of her hand.

“You will shame yourself. You will be shunned and left alone to die on the street,” Harshad called. “Do you think your father will take you back?”

Banhi stopped and turned. She backed away from both of us. Then, she walked back in the direction we had come. She gave a cry and ran to their front door and the structure shook as the door opened, then hit against the frame. “Leave her alone, Cassie,” Harshad said when I turned to follow, his hand on my arm restraining me.

“No,” I said. “Let me go. You don’t get her to a doctor? It isn’t about not having money. It’s about not letting her suffer.”

He said, “Please. Even if we take her to the free clinic, they will expect us to pay.” He said this, explaining it to me as though I were a child.

“Who will expect you to pay?”

“Not the doctors,” he said. “Bribes so the police don’t come and accuse us of…of…”

“Of what?”

“Of trying to kill her. They would ruin our family if they accuse us of a dowry murder.”

I stood and stared at him. “A what?”

“Surely you know what that is.” He stared at me. “You’ve worked with these women. Banhi and you. Have none of them shared this with you?”

I just stared at him. “Tell me,” I said.

“If we went to the hospital, the police would go to Kiran and tell him their daughter was burned by her mother-in-law.”

“But the truth…”

“Kiran would press charges. It would ruin us.”

“But Kiran is a good man. He won’t do that. He’d help.”

“And Banhi would be shamed by this. She would not be able to return to her father. She would not have a home with us anymore. She would be cast out, shamed, ruined.”

“This is why Rehani did not want me to visit.”

“Why are you trying to take her away?”

I shifted Lila a bit. She felt so heavy, her head leaning on the back of me.

“She asked me to give her work. Was that burn an accident? Tell me. Do you know?”

Harshad looked away, then back at me. “My saying will only make Rehani punish her more.”

I saw a flash of light, heard a whoosh and felt a wave of heat. I ran to their shack. Rehani’s back was to me where she stood just inside the kitchen. Banhi was standing as still as a statue, her hair in disarray, flame creeping up her arm on the sleeve of her sari, up her legs to her torso and the skin I’d seen black and oozing was now under the glow of blue flame. I heard a hissing sound, blood sizzling under the flame. All of her was aflame. She collapsed and her head hit the floor. The wrinkle on Rehani’s brow smoothed to silk. Her hands came together in prayer and she said, “The stove. She left it burning. She is careless.” Banhi’s jewel, the one she wore on her sari, the one that signified her soul, rolled away from the flame and lay there at Rehani’s feet.