Читать книгу Thank You, Anarchy - Nathan Schneider - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE|SOME GREAT CAUSE

#A99 #Bloombergville #Jan25 #SolidarityWI #NYCGA #OCCUPYWALLSTREET #October2011 #OpESR #OpWallStreet #S17 #SeizeDC #StopTheMach #USDOR

Under the tree where the International Society for Krishna Consciousness was founded in 1966, on the south side of Tompkins Square Park in the East Village, sixty or so people are gathered in a circle around a yellow banner that reads, in blue spray paint, “general assembly of nyc.” It is Saturday, August 13, 2011, the third of the General Assembly’s evening meetings.

“No cops or reporters,” someone decrees at the start of the meeting. Others demand a ban on photographs.

From where I’m sitting in the back, my hand inches up, and I stand and explain that I am a writer who covers resistance movements. I promise not to take pictures.

Just then, a heavyset man in a tight T-shirt, with patchy dark hair and a beard, starts snapping photos. He is Bob Arihood, a fixture of the neighborhood known for documenting it with his camera and his blog. People shout at him to stop; he shouts back something about the nature of public space. Soon, a few from the group break off to talk things through with him, and the discussion turns back to me.

The interrogation and harrowing debate that follow are less about me, really, than about them. Are they holding a public meeting or a private one? Is a journalist to be regarded as an agent of the state or a potential ally? Can they expect to maintain their anonymity?

After half an hour, at last, I witness an act of consensus: hands rise above heads, fingers wiggle. I can stay. A little later, I see that Arihood and the people who’d gone to confront him are laughing together.

Those present were mainly, but not exclusively, young, and when they spoke, they introduced themselves as students, artists, organizers, teachers. There were a lot of beards and hand-rolled cigarettes, though neither seemed obligatory. On the side of the circle nearest the tree were the facilitators—David Graeber, a noted anthropologist, and Marisa Holmes, a brown-haired, brown-eyed filmmaker in her midtwenties who had spent the summer interviewing revolutionaries in Egypt. Elders, such as a Vietnam vet from Staten Island, were listened to with particular care. It was a common rhetorical tic to address the group as “You beautiful people,” which happened to be not just encouraging but also empirically true.

Several had accents from revolutionary places—Spain, Greece, Latin America—or had been working to create ties among pro-democracy movements in other countries. Vlad Teichberg, leaning against the Hare Krishna Tree and pecking at the keys of a pink laptop, was one of the architects of the Internet video channel Global Revolution. With his Spanish wife, Nikky Schiller, he had been in Madrid during the May 15 movement’s occupation at Puerta del Sol. Alexa O’Brien, a slender woman with blond hair and black-rimmed glasses, covered the Arab Spring for the website WikiLeaks Central and had been collaborating with organizers of the subsequent uprisings in Europe; now she was trying to foment a movement called US Day of Rage, named after the big days of protest in the Middle East.

That meeting would last five hours, followed by working groups convening in huddles and in nearby bars. I’d never heard young people talking politics quite like this, with so much seriousness and revelry and determination. But their unease was also visible when a police car passed and conversation slowed; a member of the Tactics Committee had pointed out that, since any group of twenty or more in a New York City park needs a permit, we were already breaking the law.

Fault lines were forming, too. Some liked the idea of coming up with one demand, and others didn’t. Some wanted regulation, others revolution. I heard the slogan “We are the 99 percent” for the first time when Chris, a member of the Food Committee, proposed it as a tagline. There were murmurs of approval but also calls for something more militant: “We are your crisis.” When the idea came up of having a meeting on the picket line with striking Verizon workers, O’Brien blocked consensus. She didn’t want the assembly to lose its independence by siding with a union.

“We need to appeal to the right as well as the left,” she said.

“To the right?” a graduate student behind me muttered. “Wow.”

Just about the only thing everyone could agree on was the fantasy of crowds filling the area around Wall Street and staying until they overthrew the corporate oligarchy, or until they were driven out. As the evening grew darker, a pack of intern-aged boys walked by, looking as if they had just left a bar, and noticed the meeting’s slow progress. One of them, wearing a polo shirt, held up a broken beer mug and shouted, at an inebriated pace, “If you always act later, you might forget the now!”

Bob Arihood died of a heart attack at the end of September, after he exhausted himself photographing a march from the Financial District to Union Square. By then, the idea that the General Assembly had been planning for was a reality, spreading fast. One of his photos of the meeting survives on his blog, the only picture of its kind I’ve found. In that cluster of people around the banner, almost everyone is looking toward the camera; a guy I now know as Richie, dressed in white, is pointing right into the lens. Some look curious, some suspicious, some scared, some indifferent. I’m barely visible in a far corner of the group.

I recognize most of the others now in a way I couldn’t then. Some have had their names and faces broadcast on the news all over the world. There’s the woman from LaRouchePAC with such a good singing voice, and the group who went to high school together in North Dakota. When I showed Arihood’s picture to a friend, he recognized his former roommate from art school. I try to guess what the ones I know best were thinking, what it was exactly that they imagined they were doing there—so expectant, so at odds with one another, so anxious about being watched.

The saying “You had to be there” typically comes at the end of a joke that didn’t get the right reaction, that set up high hopes but by the time of the punch line fell flat. If you were there, after all, you’d know that something happened that really was significant or funny or worth repeating. I keep wanting to say those words again and again about Occupy Wall Street—“you had to be there,” “you had to be there!”—but I stop myself, because doing so would also be an admission of defeat. Those words are a conversation stopper. If I say them I’m giving up on even trying to convey why Occupy Wall Street was such a momentous thing and such a rare moment of political hope for us who were born during the past thirty years in the United States of America.

For nearly two months in the fall of 2011, a square block of granite and honey locust trees in New York’s Financial District, right between Wall Street and the World Trade Center, became a canvas for the image of another world. In occupied Zuccotti Park, thousands of people ate, slept, met, talked, argued, read, planned, and were dragged away to jail. Many came to protest the most abstract of wrongs—the deregulation of high finance, the funding of electoral campaigns, the erosion of the social safety net, the logic of mass incarceration, the failure to address climate change—but what they found was something more tangible. There was a community in formation, which they would have a hand in forming; there was work to be done, which they would do with people and ideas that the world outside had insulated them from ever considering.

Before the occupation itself, there was a process by which a few hundred people, inspired by what they saw happening overseas, found the wherewithal to imagine, plan, and resist. After the encampment ended, the many thousands who had experienced it faced a crisis of what to do next.

Over the course of a year of being immersed in Occupy Wall Street, I saw a veil being lifted. Etymologically, the lifting of a veil is what the word apocalypse refers to; after that, one can’t go back unchanged. The preceding world has passed, and a new revelation is at hand. Nobody who worked to make Occupy Wall Street happen imagined anything much like what actually did: it altered them and transformed them and messed with them. The movement’s most unsettling features were often the same ones that made it work—in addition to being at fault for the extent to which the Occupy joke ended up falling flat.

But disappointment is part of any apocalypse. The fact that the most radical aspirations of Occupy Wall Street remain unrealized is also a symptom of success; images that it promulgated of shutting down Wall Street and mounting a general strike became implanted in people’s minds, if even just to provide a measure of how those images failed to become manifest.

This was movement time, the nonlinear and momentous kind of temporality that the Greeks called kairos. The dumb piece of red sculpture that towers over Zuccotti Park—the “Big Red Thing”—now has in my nervous system the chill-inducing and undeserved status of Beacon of the Real, as the first thing I’d see when approaching the occupation from the subway. Under that distracting piece of corporate abstraction, a living work of art brought every aspect of life into a sharper kind of focus. It was a utopian act, but in the form of realism. With artists mainly in charge, Occupy Wall Street was art before it was anything properly organized, before it was even politics. It was there to change us first and make demands later.

And so it did. Like probably thousands of other underemployed Brooklynites who otherwise had no business being in the Financial District, I came to know that area’s twisty streets like the neighborhood I grew up in. And, now, fearing that my generation might slip back into irony and apathy and unreality, I feel an urgent, evangelistic duty to record as best I can the sliver of this reality that I experienced.

What first brought me to Occupy Wall Street, in some respects, dates back to 2001. I was in high school and had an internship at Pacifica Radio in Washington DC. My first and only reporting job there was to cover a protest against the invasion of Afghanistan, just a few days before the invasion began. I followed the course of the march, and interviewed people, and wasn’t sure whether I should be marching too or standing at a professional distance. It was a moderately impressive display, and yet of course the war went on.

Then, in early 2003, the same thing happened, only more so. The worldwide protests against the invasion of Iraq were the largest mobilization in history, and the war happened anyway. The newspapers hardly even noticed the opposition. A lot of us who were young enough to believe that we could turn back the bombers if our slogans were loud enough retreated into disappointment and the complacent cynicism of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. But those protests lodged a question in my head: What would it have taken to make a difference? What would it have taken to capture people’s imaginations and keep them from letting the politicians lead us into disaster again?

For the most part, though, I turned my attention to other things. I converted to Catholicism and studied religion. I went to graduate school and started writing for magazines. By the time the middle of 2011 came around, I was putting off finishing a quixotic book I’d been writing for years about how and why people concoct proofs about the existence of God. This put me in a fidgety mood, primed for apocalyptic distractions.

I had been watching revolutions from a distance since the beginning of the year, when people rose up and expelled dictators in Tunisia and Egypt, stirring up Libya, Bahrain, Syria, Jordan, and more. Continually refreshing my social media feeds, with Al Jazeera on in the background, I tried my best to blog each day about whatever was happening in the Middle East. I wanted to understand where these movements came from, who organized them, and how. Experts in the United States were satisfied with attributing the uprisings to global food prices and Twitter, but the revolutionaries themselves didn’t use the language of economic or technological determinism. In interviews, they seemed instead to talk about having rediscovered their agency, their collective power, their ability to act.

Over the summer, I attended a seminar in Boston with civil resisters from around the world. Some were still glowing from recent success, like the Egyptians who’d helped overthrow Hosni Mubarak, while others, like the Tibetan and the two from Burma, remained so far from what they longed for. They shared their goals and their strategies, as well as their sacrifices—for many of them, imprisonment and torture. They had arguments and epiphanies. They learned from what one another was doing and thinking, and grew stronger as a result.

During a break in the discussion, I noticed a photocopied essay by one of those at the seminar, a memoir of her time in the civil rights movement. The essay opened with a passage from a nineteenth-century poem born of the struggle over slavery. It described a moment arising, or a movement, in which a whole society is forced to choose where it stands: “Some great cause, God’s new Messiah.” When might such a moment, or a movement, come to us in the United States again? Those words became my mission.

I left that meeting with something lit up inside me. I now knew the kinds of stories I needed to learn how to tell—the stories of how people go from wanting to resist to actually doing so, of how by reasoning and creativity they learn to build power. I wasn’t interested so much in reporting on more protests, coming and going with the spectacle; I wanted to experience the planning and organizing by which the spectacle, and whatever comes of it, came about. So when I returned home to New York, I started looking for the planning process of some great cause to follow and to learn from. It turned out that this would be easier than I expected—and that the spectacle would be the process itself.

Revolution didn’t seem like such a crazy idea in 2011. Just a few weeks into the year, two dictators had already bowed to the power of the people. By late February, the victorious Egyptians were phoning in pizza-delivery orders to the occupied Wisconsin state capitol, in Madison. Unrest followed the summer’s heat to Greece, Spain, and England. Europe’s summer was Chile’s winter, but students and unions rose up there too. Tel Aviv grew a tent city.

While Tahrir Square in Cairo was still full, the boutique-y activist art magazine Adbusters published a blog post imagining “A Million Man March on Wall Street.” But the United States appeared to go quiet after Madison, its politics again domesticated by talk of the “debt ceiling” and the Iowa straw poll; when tens of thousands actually did march on Wall Street on May 12, few noticed and fewer remembered.

While following the march that day on Twitter from Florida, however, a thirty-two-year-old drifter using the pseudonym Gary Roland read about another action planned near Wall Street for the next month: Operation Empire State Rebellion, or OpESR. That tweet led him to a dot-commer-turned-activist-journalist named David DeGraw. DeGraw was working through the Internet entity known as Anonymous, which over the past year or two had been emerging from various cesspools online into a swarm of vigilantes for justice. With Anonymous, DeGraw had helped build safe networks for the dissidents of the Arab Spring. Since early 2010 he had also been writing about his vision of a movement closer to home, a movement in which the lower 99 percent of the United States would rebel against the rapacity and corruption of the top 1 percent. An Anonymous unit formed to organize OpESR, calling itself A99.

Through DeGraw’s website, Roland helped make plans. Having recently lost his job as a construction manager for a New York real estate firm, he was familiar with the city’s public spaces and the laws applying to them. He proposed that OpESR try to occupy Zuccotti Park, a publicly accessible place privately owned by Brookfield Office Properties. On June 14—Flag Day—Zuccotti Park would be its target.

Anonymous-branded videos announcing the action had begun to appear in March and got hundreds of thousands of views. Momentum seemed to be building. When the day came, though, only sixteen people arrived at Chase Manhattan Plaza, where the march to Zuccotti was to commence, and of the sixteen only four intended to occupy.

Undeterred, Roland decided to join another occupation that was beginning the same day near City Hall, a few blocks north. Organized by a coalition called New Yorkers against Budget Cuts, the so-called Bloombergville occupation would turn into a three-week stand against the city’s austerity budget. It didn’t seem to amount to much on its own, but it eventually proved to be another step building toward something that would.

“The attention we were able to get online,” David DeGraw wrote after the flop on June 14, “obviously doesn’t translate into action.” Consoling himself with the thought that the attempt was at least spreading awareness, he started talking about trying again on September 10, a date chosen in deference to the Anonymous convention of operating in three-month cycles.

More simultaneity, more synchronicity: September 10 was also the day on which a completely separate mass action was slated to happen in Washington. Seize DC, as it was called, came from a small organization called Citizens for Legitimate Government (CLG), which had experienced a period of some prominence during the Bush years.

“We’re thinking of this as a guerrilla protest,” CLG’s Michael Rectenwald told me on a bench in Washington Square Park. (In addition to being the group’s founder, chair, and “chief editorialist,” he is a professor at New York University who writes about nineteenth-century working-class intellectuals.) The goal was to mount a protest against wars abroad and corporate control at home, beginning on the eve of the tenth anniversary of the September 11 attacks but possibly continuing much longer. “We’re trying to get the maximum impact for the numbers we have,” Rectenwald said. The details would be worked out more or less on the fly.

Numbers, however, were again the problem. CLG had called for Seize DC on its seventy-five-thousand-member e-mail list, but by late August it was clear that a turnout of even a thousand wasn’t likely. This, too, had to be put on hold.

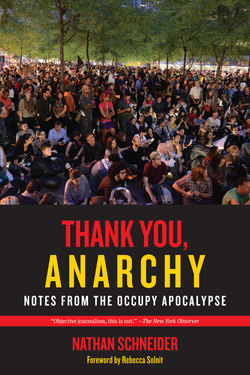

The call that came on July 13 from Adbusters was just one more among the others. Like OpESR and Seize DC, its prospects were entrusted to the Internet. The name was in the idiom of a Twitter hashtag: #OCCUPYWALLSTREET. Accompanying that was an image of a ballerina posed atop the Financial District’s Charging Bull statue, with police in riot gear partly obscured by tear gas in the background. Red letters at the top asked, “WHAT IS OUR ONE DEMAND?” At the bottom, in white, it said “SEPTEMBER 17TH”—the birthday of Adbusters founder Kalle Lasn’s mother—and “BRING TENT.” The image appeared as a centerfold in an issue titled “Post Anarchism,” which also included an article by David Graeber. With that, more or less, the magazine’s logistical guidance ended.

“What we want to play is a more philosophical role,” Adbusters’ twenty-nine-year-old senior editor, Micah White, told me in August. Not dirtying its hands with organizing became just part of the aesthetic, part of the mystique.

Almost at once, Twitter accounts, Facebook pages, and Internet Relay Chat channels started appearing and connecting. “#OCCUPYWALLSTREET goes viral,” Adbusters announced in a “Tactical Briefing” e-mail on July 26. The following day, Alexa O’Brien’s US Day of Rage declared its support for the occupation. O’Brien and the colleagues she’d found online were organizing actions on September 17 in Los Angeles, Portland, Austin, Seattle, and San Francisco, in addition to Wall Street. Her press releases and tweets became so ubiquitous that people started referring to #OCCUPYWALLSTREET and US Day of Rage interchangeably.

I first heard about the idea of occupying Wall Street while attending the planning meetings of yet another group that, since April, had been planning another indefinitely long occupation of a symbolic public space. In late July I attended one of its meetings, around a conference table in an office above Broadway shared by a handful of New York activist organizations. Those present, both in person and over video-chat, included some of the hardiest survivors of Bush-era dissent. They were mostly middle-aged, frustrated, and ready for a breakthrough. This October 2011 Coalition intended to set up camp at Freedom Plaza in Washington DC starting on October 6, in time for the tenth anniversary of the war in Afghanistan. “Stop the machine!” went their slogan, “Create a new world!”

In early August, Al Gore told TV commentator Keith Olbermann, “We need to have an American Spring.” But people all over the country were already fumbling toward an American Autumn.

What, if anything, the hubbub online actually amounted to remained opaque. “We are not a political party,” Alexa O’Brien told me when I asked her about the nature of US Day of Rage in mid-August. “We are an idea.” Here’s how she described its genesis, out of the inspiration of the Arab Spring:

I felt that something needed to be done to help people have a space where they could discuss these issues and their self-interest without ideological talking points. I asked them to list their grievances on a hashtag—US Day of Rage asked people to list their grievances. Originally we were going to put them into columns. But what ended up happening is we realized that most of the grievances, whether on the left or the right, could be linked to corrupt elections. So we decided to keep it really simple. We need to reform our elections.

The idea that emerged out of these discussions on social media was an especially drastic kind of campaign finance reform: “One citizen. One dollar. One vote.”

She went on:

I wouldn’t even call myself an activist. I’m a normal nobody. I’m a nobody. I always say that. For me, this is an avocation. It’s an idea of service to my country, to my community, and to other people. In the beginning it was me, but I have to say “we,” because there was the hashtag as well. And it’s not me. In the beginning we had the hashtag, and we had a Facebook page. And what we did was we built a platform.

The platform also had a theme song, which appeared on the website in the form of an embedded YouTube video: the theme from the 1970s show Free to Be . . . You and Me.

On August 23, an Adbusters e-mail featured a video of Anonymous’s headless-man logo and a computerized voice declaring support for #OCCUPYWALLSTREET. Soon there were rumors that the Department of Homeland Security had issued a warning about September 17 and Anonymous; Anonymous bombarded mainstream news outlets with tweets demanding that they cover the story.

Micah White:

I see stuff on Twitter from people saying that we had interaction and then we cut off communication, but we never had any. I never communicated with Anonymous.

Alexa O’Brien:

They [Homeland Security] believe that we are high-level Anonymous members, which is really a joke. . . . We have had no contact with Anonymous. And that’s the honest truth.

An occupation, by definition, has to start with people physically present. Social media, even with whatever aid and cachet Anonymous might lend, isn’t enough—witness the failure of OpESR. Until August 2, when the NYC General Assembly began to meet near the Charging Bull statue at Bowling Green, #OCCUPYWALLSTREET was still just a hashtag.

That first meeting was hosted by the coalition behind Bloombergville, New Yorkers against Budget Cuts, which had exchanged e-mails with Adbusters. Others learned about the assembly at a report-back from anti-austerity movements around the world at the nearby 16 Beaver Street art space on July 31. What was advertised as an open assembly began like a rally, with Workers World Party members and those of other groups making speeches over a portable PA system to the hundred or so people there. But the anarchists started to heckle the socialists, and the socialists heckled back. The meeting melted down. Here’s how one participant, Jeremy Bold, described what took place in an e-mail the next day:

[A] few participants were adamantly opposed to the initial speak-out sessions being voiced through the loudspeaker, proclaiming that it was “not a general assembly” and demanding that a more open GA be created. Though organizers quickly shifted to the general assembly structure for the meeting, maintaining use of the loudspeaker caused the opposed participants to organize their own assembly, causing a brief bifurcation in the group: one group utilizing the GA structure of an open floor but maintaining the loudspeaker to contend with the traffic noise, the other group seating themselves in a circle closer to Bowling Green park. The breakaway faction had objected to the format because it appeared to function more like a rally than a GA and expressed concerns about being forced to speak under a particular political party or viewpoint [, and the breakaway faction] voiced this criticism; as they broke off to begin the GA, participants were stuck between the two groups. As the power began to die from the loudspeaker, the group voted by simple majority to move to the traditional GA and joined the circle, in which the GA was already under way.

Those who stuck around got what the anarchists wanted, and perhaps more: a leaderless assembly, microphone-free and in a circle, that dragged the 4:30 P.M. event on until 8:30, with some people staying around to talk until eleven o’clock. They started using the language of the 1 percent versus the other 99—independently, it seems, of David DeGraw and A99. Working groups formed to do outreach, to produce media, to provide food.

Despite the presence of people from various contingents of the sectarian left who made their affiliations known with T-shirts and specialized rhetoric, none of these groups could dominate the NYC General Assembly. New York’s activists at that point were splintered and frustrated, and no one group could do much of anything on its own. One of them with a considerable role, the invitation-only Organization for a Free Society, was not the kind to announce its presence, and its members seemed to operate as individuals, not as representatives of a bloc. Even the anarchists, who set the format of the GA and furnished some of its more influential interventions, were in no position to run the show entirely. David Graeber told me,

The anarchist scene in New York had been very fragmented. The insurrectionists versus the SDS people—there’d been all these splits. It had become a little dysfunctional. The New York scene was fucked up, to be perfectly honest.

Describing the makeup of the GA, Graeber continued:

There was one fairly small crew—capital-A insurrectionary anarchists, they were there. But there was mainly what I like to call the small-a anarchists, people like myself.

I couldn’t tell you what kind of anarchist I am. I don’t feel any need to work in groups that are made up exclusively or mainly of anarchists, as long as they operate on anarchist principles. I see anarchism more as a way of doing things, a broad series of ethical commitments and principles, rather than an ideology. So people like that, there were a lot of them.

In lieu of anything else, small-a anarchy was an acceptable enough common denominator for the anarchists and everyone else. On that basis, the General Assembly would continue to meet about once a week.

The second meeting I attended was on August 20, the fourth in all. It was relatively productive at first, even if short on consensus. The group didn’t, for instance, make any outright commitment to nonviolence, largely because its members couldn’t agree on what it would mean to do so. No text for the Outreach Committee’s fliers could be passed. But people wiggled their fingers in the air when they liked what was being said and wiggled them down at the ground when they didn’t, so through these discussions everyone got to know one another a little better.

Soon, even that modicum of process started to fail. Georgia Sagri, a performance artist from Greece, paced around the periphery of the circle with a large cup of coffee in her hand, making interjections whether or not she was “on stack” to speak. She seemed less interested in planning an occupation than in the planning meeting itself. “We are not just here for one action,” she declared. “This is an action. We are producing a new reality!” The pitch of her voice rose and then fell with every slogan. “We are not an organization; we are an environment!”

Georgia’s powers of persuasion and disruption were especially on display when the discussion turned to the Internet Committee. Drew Hornbein, a red-haired, wispy-bearded web designer, had started putting together a site for the General Assembly. Georgia thought he was doing it all wrong. She didn’t trust the security of the server he was using—not that she knew much about servers—and wanted to stop depending on Google for the e-mail group. Her concern was principle, while his was expediency.

As Georgia and her allies denounced Drew publicly, he apologized as much as he could, but then he eventually got up and left the circle with others who’d also had enough. “I’m talking about freedom and respect!” Georgia cried. “This is not bullshit!”

She continued to hold the floor, proposing every detail of what the website would say and how it would look, reading one item at a time from her phone and insisting that the General Assembly approve it. The facilitators seemed exasperated. A passerby began playing Duck, Duck, Goose on the shoulders of those sitting under the Hare Krishna Tree.

The thrill I’d felt the previous Saturday turned to pretty thoroughgoing disappointment. I abandoned my reportorial post: I left early, after three and a half hours.

On the way out, I ran into a couple I knew from the October 2011 Coalition, Ellen Davidson and Tarak Kauff, who were just arriving from another gathering in Harlem. They had met each other at protests over the past few years, in jail after an action at the Supreme Court in DC, and in Cairo during a mobilization against Israel’s blockade of the Gaza Strip. I updated Tarak—who had served in the army in the early 1960s and could still do a hundred push-ups—on what had been going on. None of it appeared to surprise or trouble him.

“It’s really, really hard,” he said in his Queens accent, as the Internet Committee proposals ground through consensus a few steps away. “They’re doing fine.”

Micah White of Adbusters said, when I called him on August 12:

The worst outcome would be to get there and they just fumble it by doing this whole lefty game we always play, which is self-defeatist. We go there, make some unreasonable demand, like, we want to abolish capitalism and we won’t leave until we do. And well, that’s like the war on terrorism; that’s an impossible dream. Or they just squander it by being some hipster, anarchist insurrection like, we’re gonna smash some stores and make a spectacle. And everyone’s like, “Why?”

Because we have something beautiful going here. So we’re trying to rise above the sectarian clashings of whether or not US Day of Rage is tweeting too much or whether or not the libertarians are—you know? And reach out to the Tea Party too. This is a moment for all of America.

I don’t see why this has to be a lefty moment or a righty moment, because this is a moment for us to reinvent democracy in America, because it’s getting to be too late. If we don’t do it now, we are reaching the end.

In the NYC General Assembly, as well as on the Internet, the idea of “one demand” that Adbusters had promulgated was a topic of perpetual discussion. Some of the proposals that were being suggested:

Impose a Tobin tax (or a “Robin Hood tax”) on financial transactions, a popular proposition among some economists for simultaneously bringing the most speculative markets a bit more under control while generating revenue for social programs. This idea was described in one of the planning GAs on a photocopied sheet of paper signed under the activist pen name “Luther Blissett.”

Restore the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which was repealed by Bill Clinton in 1999. It prevented investment banks from gambling with money deposited in their commercial affiliates, putting a further brake on speculation and lessening the public’s exposure to the banks’ risk.

Overturn the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, which massively deregulated the campaign finance system.

Demand universal employment in New York, with the accompanying socialist mantra “A job is a right!”

“End the Fed.” The various libertarian contingents (and fans of the online documentary sensation Zeitgeist) were especially insistent on this proposal for the abolition of the Federal Reserve.

“End the wars, tax the rich.” This slogan of the antiwar movement tended to come from older voices, and it figured prominently in the October 2011 Coalition.

None of these was to win out. “One demand is dangerous,” I remember someone saying in Tompkins Square Park. “This is for the long haul.” Another added, “Personally, I’m not asking anything of Wall Street.” And another: “Once you get pigeonholed into one demand, it becomes easy to be just about winning or losing.”

At first the “one demand” was simply hard to agree on. But gradually its absence seemed to make more and more sense.

The August 27 GA meeting didn’t happen because there was a hurricane that weekend—weird for New York City, just like the earthquake a few days earlier. I missed the following weekend’s meeting because I went to the October 2011 Coalition’s retreat at Ellen and Tarak’s house up in Woodstock, where a dozen organizers holed up for two nights and a long day of planning the DC occupation. They were eating well, singing protest songs, and debating the theories of Gene Sharp, the scholar who from his home office in Boston helped inspire revolutions as far away as Serbia and Egypt. Everyone in the group came with some deep well of experience—a Ralph Nader presidential campaign manager, leaders of major antiwar groups, and the gruff Veterans for Peace, whose youthfulness returned to them with any talk of tactics. After decades of trying leaderless activism, they affirmed to one another that identifying leaders is really okay. It was conspicuous that only the very youngest—a sober-minded, thirty-eight-year-old Israeli who managed their website—had any real Internet expertise.

The goal of the occupation was to create a space for people to come into their own, explained Margaret Flowers, a pediatrician and a mother of three teenagers, who became radicalized while fighting for single-payer health care. She was among those who first conceived of the plan for October 6, but Margaret and the other organizers realized that the moment they succeeded—if they did, by some definition of the word—would be the moment they’d have to let go and let this take a life of its own.

“I just think of how I raised my children,” she said.

The organizers gathered in the living room the first night, after dinner on the screened-in porch out back, for a meeting over Skype with a guru-type old man in Santa Cruz. His expertise was in a technique for “grounding” oneself with chi—or energy, or qigong, or the earth, or plain love—pointing one’s attention to the ground underneath and feeling oneself as connected to it. For too long, they put up with him explaining all this—as strange women strolled by in the background, occasionally pausing to look at the camera or to stand in as demonstration subjects when he attempted to explain just what he was talking about and what it had to do with revolution. Tarak fell asleep in his chair as it became clear that the guy was quite pathetically just in search of a market, a spot on the website, and access to a huge crowd so he could jizz his metaphysics on them and make a buck in the process. For the rest of the retreat they’d joke about this—“Are you grounded?” But a few weeks later, standing again and again before columns of angry cops, I’ve got to say that I fell back on what little I’d gleaned of his technique.

The rest of the retreat was far more reasonable. Sketching notes on giant sheets of paper on an easel, the organizers set out to assess what their protomovement was up against and what its strengths and weaknesses were. While debate about the “one demand” had come to an impasse in Tompkins Square Park, this group decided much more methodically not to state demands at the outset. For months already, they had been developing a fifteen-point set of proscriptions on issues ranging from military spending to public transportation, but now they started thinking that the group wasn’t strong enough—not yet—to make such demands heard. They concluded from their discussion of Gene Sharp that there was no point in making a demand until they were in a position to force the system to accept it. Instead, their goal would be to host an open conversation at their occupation in the capital, to spread a culture of resistance to the illegitimate politics of Washington. Given where they were at the time, the first priority was to claim that space, cause a disruption, and grow.

The concluding topic of the retreat, after Goals and Strategy and Tactics were settled, was Message. Over wine that Saturday night, the group tripped and turned over words until finally landing on something that would let them go to bed satisfied: “It Starts Here.” The slogan, however, was destined for obsolescence; by the time they pitched their tents in October, they would seem like latecomers.

Reports about the planned occupation of Wall Street trickled out slowly online, and consequently they betrayed the biases of the Internet: much discussion of Adbusters, US Day of Rage, and Anonymous, but hardly anything about the General Assembly—which, despite not having an active website, still constituted the closest thing to a guaranteed turnout on September 17.

Among the most prolific early chroniclers was Aaron Klein of the right-wing news website WorldNetDaily. His articles claimed that September 17 could bring “Britain-style riots,” that “Day of Rage” was a reference to the terrorism of the Weather Underground, and that the billionaire George Soros—who else?—was behind it all. Because Stephen Lerner of the Service Employees International Union had been murmuring about wanting to see an uprising against banks, Klein concluded that the union was involved, together with the remnants of ACORN. None of it was true; when people from the General Assembly tried to reach out to unions and the like, none wanted to touch the idea of an occupation with a ten-foot pole. But Klein thought he saw exactly the kind of vast left-wing conspiracy he had been outlining in his book, Red Army: The Radical Network That Must Be Defeated to Save America, which was scheduled for release in October. Before most Americans had heard of #OCCUPYWALLSTREET, Klein’s gumshoeing inspired a new fund-raising and lobbying campaign from the conservative AmeriPAC: “On September 17th,” the title of one solicitation warned, “Socialists Will Riot Like Egyptians in All Fifty States.”

My next chance to go to an NYC General Assembly meeting was on September 10, a week before the date Adbusters had named. The facilitators this time were especially expert—impatient with off-topic speeches and creative with synthesizing what was said into passable proposals. Things got done. But really, most of the work was already being handled by the various formal and informal committees that had grown out of the General Assembly. I was learning that the point of a consensus process like this is often less to make decisions than to hear one another out; individuals and subgroups can then act autonomously, respecting the assembly while sparing it the burden of micromanagement.

On September 1, nine people had been arrested while attempting to sleep legally on the sidewalk of Wall Street as a “test run,” and a video of it was getting traction online. A student group was rehearsing a flash mob to Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.” The Food Committee had raised eight hundred dollars—the only funding that I heard mentioned—which was about a quarter of the goal for supplying water and peanut butter sandwiches. The National Lawyers Guild would be sending observers in green caps. More than any one plan, there were plans.

I didn’t see Georgia Sagri there on September 10. Gary Roland showed up with an actress he’d met at Bloombergville; they had gone on a bike trip around the country but then decided to come back to see what would happen on the 17th. There was enough of a crowd that the facilitators had to demonstrate the “people’s microphone,” which would become a hallmark of the movement: the speaker addresses the audience in short phrases, and those who can hear repeat them in turn for the benefit of those who can’t. Less can be said that way, and less quickly, but more actually tends to be heard.

In the three weeks since the previous GA meeting I had attended, the mess had congealed into common wisdom. Frustrations were past, folded into the present, and turned into lessons. Some of these planners would later be accused of belonging to a secret leadership cabal behind the leaderless movement; if they were, it was the result of nothing more mysterious than having come to know and trust one another after a month and a half of arguing, digressing, and, occasionally, achieving consensus.

The Tactics Committee gave its report. An occupation right in front of the Stock Exchange seemed unfeasible and overly vulnerable. The previous week, the GA had decided to convene an assembly on September 17 at Chase Manhattan Plaza. The committee was coming up with contingencies, and contingencies for contingencies, in case that plan didn’t work. In all likelihood there would be a legal encampment along sidewalks, which many had done during Bloombergville. Despite Adbusters’s initial suggestion to “bring tent” and the rapper Lupe Fiasco’s promise to donate fifty of them, tents would probably be too risky—though it all depended on how many people would be there and what those people would be willing to do. As in Cairo and Madrid, the encampment would have to form itself.

Keeping tactics loose might also be safer. Everyone assumed there were cops in the group—I, for one, had my short list of suspects—and the less you plan ahead, the less they can plan for you.

By this point, the idea of making a single demand had completely fallen out of fashion. After a month and a half of meetings, those in the General Assembly were getting addicted to listening to one another and being heard. Rather than discussing the Glass-Steagall Act or campaign-finance reform, they were talking about making assemblies like this one spread, around the city and around the country. The process of bottom-up direct democracy would be the occupation’s chief message at first, not some call for legislation to be passed from on high. They’d figure out the rest from there.

I was still wrapping my head around this. Everyone was. This was a kind of politics most had never quite experienced, a kind apparently necessary even if its consequences seemed eternally obscure.

Drew Hornbein, who’d almost left the movement after how he’d been treated at the meeting three weeks earlier, was back. “What’s really keeping me in this is the idea of a general assembly, of the horizontal power structure and decision making,” he said. Mike Andrews—a tall, well-muscled book editor who usually spoke for the Tactics Committee—told me about how he felt after being at a GA meeting:

It pushes you toward being more respectful of the people there. Even after General Assembly ends I find myself being very attentive in situations where I’m not normally so attentive. So if I go get some food after General Assembly, I find myself being very polite to the person I’m ordering from, and listening if they talk back to me.

Maybe assemblies like this could even become a new basis for organizing political power on a larger scale. Of course, in the months to come this would be exactly what happened; as the call to occupy spread, assemblies followed. From Boston to Oakland to Missoula, Montana, activists wiggled fingers in horizontally structured meetings, using a common language to discuss problems both local and global—just as was hoped for, just as was planned. But the fact that there was a plan doesn’t mean that the plan was complete, or reassuring, or guaranteed to have the intended effect.

A spree of decisions passed by consensus the night of September 10. There would be no appointed marshals or police negotiators; if the police wanted to negotiate, it would have to be with the whole assembly. The General Assembly would start on the 17th at three o’clock—“and if we’re in jail we start it there.” A few rebellious minutes after ten, when the park was supposed to be closed, the meeting ended, and we huddled around tables at Odessa, a nearby diner, for drinks.

Throughout the week before September 17, there were committee meetings, civil-disobedience training sessions, and warm-ups. People from all over started sending pictures of themselves holding signs with their grievances against Wall Street, which were posted at wearethe99percent.tumblr.com. When the Arts & Culture Committee put on midday yoga classes and speak-outs in front of the Stock Exchange, onlookers were baffled, but that didn’t matter. “I’ve never felt so liberated, so free!” one of the planners told me, a Brazilian doctor studying for a master’s in public health. He was carrying around with him a hefty copy of Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid.

Also in front of the Stock Exchange one of those days was a man in a giant white no. 4 lottery ball suit with an Uncle Sam hat on top that said “justice.” The suit, he told me, had been created for a business of his then in litigation. Next to him his colleague held a sign that said “Please Re-Elect PRESIDENT OBAMA Or The little guy Has No Chance.” I asked if they were involved in occupying Wall Street, and they informed me they weren’t. For them, the choice of location was a practical matter.

“We were at Times Square once,” the man with the sign said. “It was just too crowded.”

That week, too, Anonymous threatened a fearsome attack on bank websites. And more. No one could know everything that was happening, much less whether it would work.

“Maybe the General Assembly has been the really big central planner, but I don’t know,” Drew Hornbein told me that week over lunch. “There might be a lot of other stuff going on.” I mentioned the group organizing for October 6, and he asked me to send him some links. If Wall Street didn’t work out he could help with that.

There was a small meeting a few days before the 17th in the back of a bar in the Bed-Stuy section of Brooklyn—for outreach, to talk about #OCCUPYWALLSTREET with some locals. It’s a mostly black neighborhood, yet all but one of us—hip-hop elder Radio Rahim—were white. Still, “What a propitious moment this is!” predicted a retired schoolteacher. “This is the moment.”

“This is fucking really new, this is the definition of a truly radical movement,” said one of the graduate students from the General Assembly. “So, yeah, we’re gonna win.”

Occupation was on my mind constantly as the date approached, but it was still a mostly secret fixation. Norman Mailer’s mesmeric account of the 1967 march on Washington, Armies of the Night, was on my nightstand. I saw “OCCUPY WALL STREET SEPTEMBER 17” scrawled in chalk near the fountain in Washington Square Park. On the whole, though, the city’s landscape seemed innocent of what was being planned for it—if what was happening was really planning at all.

On September 16, the night before whatever it was was slated to begin, I opted to pass on covering a civil-disobedience training to satisfy my curiosity about an occupation-themed Critical Mass bike ride setting out from Tompkins Square Park. Online, Anonymous associated the ride with something called “Operation Lighthouse.”

A critical mass there was not, unless you counted the police, who were stationed at every corner of the park and periodically motorcycled by to monitor the handful of bicyclists waiting in vain for more to turn up. The bicyclists accepted soup and coffee from enterprising evangelists and obtained a tepid blessing for the next day’s undertaking. Rather than invite the police to form a motorcade around the group, those present decided to leave the park one at a time and reconvene downtown for a scouting mission.

After riding into the Financial District and passing by Wall Street, I stopped in front of a boxing match two blocks south of the New York Stock Exchange. Seeping out from the Broad Street Ballroom, an inexhaustible electronic beat surged under a looping bagpipe track. Well-decorated couples and gaggles paid their forty-five dollars per person to slip through the doors and into the crowd surrounding the ring, where two sinewy fighters were bouncing back and forth, punching and kicking each other. They were following Thai-style rules, but the scene looked more like the last days of Rome. Along the back wall stood a row of Doric columns.

On the sidewalk, looking in and around, I recognized Marisa Holmes from the General Assembly meetings as she veered away from the entrance to the boxing match. She looked worried, but she usually looked worried, so it was hard to be sure. We nodded to each other knowingly, like spies, and maybe for a moment even questioned whether to acknowledge each other publicly. But we did, and we exchanged our reconnaissance.

She had just been down at Bowling Green, where a Department of Homeland Security truck was parked. Barricades surrounded the Charging Bull statue like a cage. I told her I had been up at Chase Manhattan Plaza, north of Wall Street, and it was also completely closed off. A stack of barricades sat in wait just across a narrow street. We stood in silence and watched as the fight ended, the combatants making a gesture of good sportsmanship. Marisa continued north to Wall Street, and I got on my bicycle to go home.

Nights in the Financial District are desolate, even ones with scattered boxing fans and police officers preparing for God-knows-what. One can feel the weight of the buildings overhead, all the more because there are so few people around to help bear the load. The buildings seemed completely different, however, while I rode home over the Manhattan Bridge. They were distant, manageable, and light. Rolling high above the East River and looking back at them, I wondered if they had any idea what was coming.