Читать книгу Thank You, Anarchy - Nathan Schneider - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD|MIRACLES AND OBSTACLES

REBECCA SOLNIT

I would have liked to know what the drummer hoped and expected. We’ll never know why she decided to take a drum to the central markets of Paris on October 5, 1789, and why that day the tinder was so ready to catch fire and a drumbeat was one of the sparks. The working women of the marketplace marched all the way to Versailles, occupied the seat of royal power, forced the king back to Paris, and got the French Revolution rolling. It was then the revolution was really launched, more than the storming of the Bastille—though both were mysterious moments when citizens felt impelled to act and acted together, becoming in the process that mystical body civil society, the colossus who writes history with her feet and crumples governments with her bare hands.

She strode out of the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City: parts of the central city collapsed in that disaster, but so did the credibility and the power of the PRI, the Institutional Revolutionary Party that ruled Mexico for seventy years. These transformative moments happen in many times and places, as celebratory revolution, as terrible calamity, and they are sometimes reenacted as festivals and carnival. In these moments the old order is shattered, governments and elites tremble, and in the rupture civil society is reborn. The old rules no longer apply in that open space of rupture. New rules may be written, or a counterrevolution may be launched to take back the city or the society, but the moment that counts is the one in which civil society is its own rule, taking care of the needy, discussing what is necessary and desirable, improvising the terms of an ideal society for a day, a month, a season, the duration of the Paris Commune or the Oakland Commune (as Occupy Oakland was sometimes called), or the suspension of everyday life during disaster.

Those who doubt that the significance of these moments matter should note how terrified the authorities and elites are when such moments erupt. Those who dismiss them because of their flaws need to look harder at what joy and what hope shine out of them and ask not what these moments produce in the long run but what they are in their heyday (though they often produce profound change in the long run—and when it comes to long runs, there’s always that official of the Chinese government who some decades back was asked what he thought of the French Revolution: “Too soon to tell,” he said).

In these moments of rupture, people find themselves members of a “we” that did not exist, at least not as an entity with agency and identity and potency, until that moment; new things seem possible, or the old dream of a just society reemerges, and for a little while it shines not just as a possibility but as how people live with one another. Utopia is sometimes the goal, it’s often the moment, and it’s a hard moment to explain, since it usually involves hardscrabble ways of living, squabbles, and eventually disillusion and factionalism—but also more ethereal things: the discovery of personal and collective power, the realization of dreams, the birth of bigger dreams, a sense of connection that is as emotional as it is political, and lives that change and do not change back to what they were before, even when the glory subsides.

Sometimes the earth closes over these moments, and they have no obvious consequences—sometimes they’re the Velvet Revolution and the fall of the Berlin Wall and all those glorious insurrections in the East Bloc in 1989, and empires crumble and ideologies fall away like shackles. Occupy was such a moment, and one so new that it’s hard to measure its consequences. I have often heard that Freedom Summer in Mississippi registered some voters and built some alliances, but more than that, the young participants were galvanized into a feeling of power, of commitment, of mission, perhaps, that stayed with them as they went on to do a thousand different things that mattered and joined or helped build the slow anti-authoritarian revolution that has been unfolding for the last half century or so. It’s too soon to tell.

Aftermaths are hard to measure and preludes are often even more elusive. And one of the great strengths of this book is its recounting of the many people who laid the fire that burst into flame on September 17, 2011, giving light and heat to many of us yet. The drummer girl of that moment in Paris walked into a group where many people were ready to ignite, to march, to see the world change—injustice and difficulty as well as hope and devotion make these conflagrations. We need, with every insurrection, revolution, and social rupture to remember that we will never know the whole story of how it happened and that what we can’t measure still matters.

Early in this superb book, Nathan Schneider cites Mike Andrews talking about how the general assemblies of the group by that name, the General Assembly of New York City, with their emphasis on egalitarian participation, respect, and consensus decision making, retooled him: “It pushes you toward being more respectful of the people there. Even after General Assembly ends I find myself being very attentive in situations where I’m not normally so attentive. So if I go get some food after General Assembly, I find myself being very polite to the person I’m ordering from, and listening if they talk back to me.” This is the kind of tiny personal change that can be multiplied by the hundreds of thousands, given the number of Occupy participants globally. But there have been quantifiable consequences too.

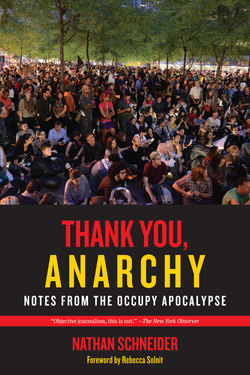

Everyone admitted almost immediately after Occupy Wall Street (OWS) appeared in the fall of 2011 that the conversation had changed—the brutality and obscenity of Wall Street was addressed, the hideous suffering of ordinary people crushed by medical, housing, and college debt came out of the shadows, and Occupy became a point at which people could testify about this destruction of their hopes and lives. California passed a homeowners’ bill of rights to curtail the viciousness of the banks, and Strike Debt emerged as an Occupy offshoot in late 2012 to address indebtedness in creative and insurrectionary ways. Student debt came up for discussion, and student loan reform began in various small ways. Invisible suffering had been made visible.

Occupy Wall Street also built alliances around racist persecution, from the Trayvon Martin case in Florida to stop and frisk in New York to racist bank policies and foreclosures in San Francisco, where a broad-based housing rights movement came out of the Occupy movement. It was a beautiful movement, because the definition of “we” as the 99 percent was so much more inclusive than almost anything before, be it movements focused on race or gender, or on class when class was imagined as the working class against a middle class that also works for a living (rather than against the elites that were christened the 1 percent in one of Occupy’s most contagious memes). Though the movement abounded in young white people, many kinds of people were involved, from kids to World War II veterans and ex–Black Panthers, from libertarians to liberals to insurrectionists, from tenured to homeless to famous.

And there was so much brutality, from the young women pepper-sprayed early on at an OWS demonstration and the students famously pepper-sprayed while sitting down peacefully at UC Davis to the poet laureate Robert Hass, clubbed in the ribs at UC Berkeley’s branch of Occupy, to eighty-four-year-old Dorli Rainey, assaulted by police at Occupy Seattle, and the Iraq War veteran Scott Olsen, whose skull was shattered by a projectile fired by Oakland police. The massive institutional violence made it clear Occupy was a serious threat. At the G-20 economic summit in 2011, President Dmitry Medvedev of Russia warned, “The reward system of shareholders and managers of financial institutions should be changed step by step. Otherwise the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ slogan will become fashionable in all developed countries.” That was the voice of fear, because the 99 percent’s realized dreams were the 1 percent’s nightmares.

We’ll never know what the drummer girl in Paris in 1789 was thinking, but thanks to this meticulous and elegant book, we know what one witness-participant was thinking all through the first year of Occupy, and what many of the sparks and some of the tinder were thinking, and what it was like to be warmed by that beautiful conflagration that spread across the world, to be part of that huge body that wasn’t exactly civil society but was something akin and sometimes even larger, as Occupy encampments and general assemblies spread from Auckland, New Zealand, to Hong Kong, from Oakland to London, and to many small towns and counties in 2011. Some Occupy encampments lasted well into 2012, and others spawned things that are still with us: coalitions and alliances and senses of possibility and frameworks for understanding what’s wrong and what could be right. It was a sea change, a watershed, a dream realized imperfectly (because only unrealized dreams are perfect), a groundswell that is still ground on which to build.