Читать книгу Settler Colonialism, Race, and the Law - Natsu Taylor Saito - Страница 38

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Contemporary Violence

ОглавлениеThe officially sanctioned elimination of Indigenous peoples is often dismissed as a thing of the past, masking the extent to which its legacy permeates American culture, allowing Indians to be killed with impunity. As of 2012, the violent crime rate on reservations was two and a half times that of the general population, Indigenous women were being raped or sexually assaulted four times more frequently than other US women, and on some reservations women were being murdered at ten times the national average.62 Almost 90 percent of the survivors of rape or sexual assault reported non-Indigenous perpetrators.63 Nonetheless, the Justice Department, with exclusive jurisdiction over such crimes, was filing charges in only about half of the murder cases and a third of the sexual assault cases.64 In a 2019 report on its inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, the Canadian government described the crisis as part of a “genocide” that “has been empowered by colonial structures,” but the United States has yet to respond to the crisis, equally severe, on this side of the border.65

In some jurisdictions it is only recently that murders of an American Indian are treated as crimes. In the winter of 1972 Raymond Yellow Thunder, a fifty-one-year-old Oglala Lakota, was picked up by two young White men in Gordon, Nebraska, close to the border of the Pine Ridge Reservation. They severely beat and stripped Yellow Thunder, and threw him into an American Legion dance hall to be further humiliated and abused. His body was found a week later, but his relatives were unable to convince the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the FBI, or local authorities to take the murder seriously.66 Only after several hundred American Indian Movement activists and supporters descended on Gordon were serious criminal charges filed against the perpetrators, making them the first White people in the history of Nebraska to be imprisoned for killing an Indian.67

In early 1973, the United States initiated a seventy-one-day siege of AIM members and supporters gathered at Wounded Knee, the site of the 1890 massacre. Claiming an AIM “occupation,” the federal government sent special warfare experts, military personnel, armored personnel carriers, grenade launchers, and aircraft to the scene and placed an Army assault unit nearby, on full alert. Ultimately, “more than 500,000 rounds of military ammunition were fired into AIM’s jerry-rigged ‘bunkers’ by federal forces.”68 The following year, federal agents worked closely with handpicked tribal leaders and BIA police to subvert the election of AIM leader Russell Means as president of the Pine Ridge tribal council, in part because Means’s election would derail federal plans to appropriate a portion of the reservation rich with uranium and other natural resources.69 Between 1972 and 1976 nearly seventy AIM members and supporters on the Pine Ridge Reservation were murdered, giving the reservation a documented political murder rate equivalent to that experienced in Chile following the 1973 US-backed coup that killed its president Salvador Allende.70

What accounts for the intensity of the governmental reaction to American Indian activism during this era? Political activists and organizations around the country were being repressed routinely, and often lethally, but no other group met with the overwhelming military force seen at Wounded Knee and no other community was subjected to politically sanctioned murders at the rate seen on Pine Ridge.71 To understand the distinction, we need to remember that most—although certainly not all—political movements of the 1960s and 1970s were struggling for inclusion in the American settler polity. By contrast, American Indian activists, at the behest of traditional elders, were bringing the illegitimacy of the occupation of their lands to the attention of the world.

The Wounded Knee siege—like the recent resistance at Standing Rock—focused on treaty rights that, if enforced, could encourage a host of other land claims.72 According to legal scholar Russel Barsh, by 1900 the United States had asserted jurisdiction over some two billion acres of Indigenous territory. “Half of this area was purchased by treaty or agreement at an average price of less than seventy-five cents per acre,” 325 million acres “were confiscated unilaterally by Act of Congress or Executive Order, without compensation,” and another 350 million acres in the “lower” forty-eight States and Alaska had been taken “without agreement or the pretense of a unilateral action extinguishing native title.”73 By 1970, even the Interior Department was warning that the United States had never acquired valid title to about one-third of its purported land base.74

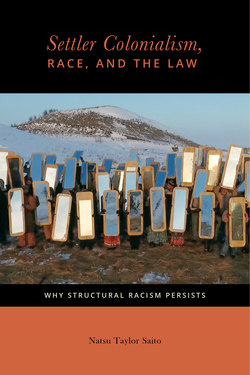

These issues could have been—and could still be—addressed straightforwardly, through negotiations with the Indigenous nations involved. Instead, the state has chosen to ignore its legal obligations in favor of continued repression. Thus, in the winter of 2016–17 Standing Rock witnessed a militarized response reminiscent of Wounded Knee in 1973, with chemical weapons, concussion grenades, so-called rubber bullets, LRAD sound devices, and water cannons unleashed on unarmed opponents of the pipeline construction.75 The settler state has never acknowledged any limitations when responding to Indigenous resistance. In 1792 Thomas Jefferson opined that “the native possessors” had “no right of soil” with respect to “a white nation settling down and declaring that such and such are their limits.”76 Some 225 years later, this characterization echoed in the Army Corps of Engineers’ demand that Standing Rock water protectors retreat to the reservation, and its pretense that “to protect the general public” it was “necessary” to treat those who remained on unceded treaty lands as “trespassers” subject to forcible removal and criminal prosecution.77