Читать книгу Vista Del Mar - Neal Snidow - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1 Meter to the Black

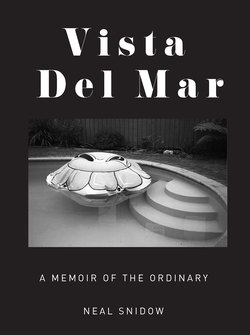

IN 1996 I began to make pictures of my hometown in Southern California. A beach town, it offered photogenic attractions like sunsets and “views,” but these weren’t what drew me. Instead, I chose as my subjects details of the suburbia in which I had grown up, apartment façades, backyards, bits of parks and schools, as well as odd, anonymous objects—railings, fences, electric meters. Like my subjects, practically invisible myself in my middle-aged pursuits, I photographed these methodically from a tripod onto black-and-white film, a wordless man bent over the camera framing images of a retaining wall or ground littered with eucalyptus leaves.

It’s hard to remember now why this project presented itself with such force, but one of the main causes would certainly have been the great grief my wife and I were then experiencing. After years of trying to have children, we’d lost a horribly expensive in vitro pregnancy, our last chance, or so we felt, at being parents, and were devastated. A painful blankness took hold of life. My wife would come home from her work each day in what seemed to me a white, chalklike haze of hurt. As for me, on semester leave from my job teaching English, I had plenty of time to stew, and in a genteel, steady, and prodigious way, like the pale host of my Virginia forebears, I’d drunk from March through May until I couldn’t drink anymore. The drink, the triple Scotches doubled and trebled, had achieved its familiar tincture of depression, a permanent iris effect like a soiled copper wash at the edge of things, a sort of peripheral yellow the acid hue of development chemistry.

I felt deeply lost. Then, like a sudden punctuation mark, I felt a chest pain one afternoon while I was cooking dinner. I kept sautéing onions, wondering what to do, but the pain didn’t stop. At the emergency room, all tests for this fugitive heartache turned negative, but during the night I spent under observation in the hospital, the larger questions of mortality—of what Emerson called “the lords of life”—kept appearing as embodied dream figures in my half sleep, querulous old men losing their way to the bathroom, and strapping night nurses guiding them to their beds in loud, hectoring voices. At one point early in the morning, a strange woman strode from nowhere into the room as though in a James Thurber cartoon, looked brightly at me, and then at the patient heretofore hidden behind a screen in the next bed. “Oh, you have to see this!” she said, and cheerfully threw the curtain aside to reveal my absolute twin, a bearded middle-aged look-alike who grinned ecstatically at me like a lost brother before bursting into the stuttering baby talk of a stroke victim.

As a lifelong reader, it was disappointing in a time of crisis to see how little solace there was in this central activity of my personality. As if in a B movie, I could see a hand dipping fatefully into the motel nightstand for the Gideon Bible, therein to find that peace that passeth understanding in some psalm or other, but this melodramatic instant never arrived. Instead I continued to plow through my current book, something by the Jungian James Hillman. I was feeling the double bind of interest and frustration that talk about the soul brings to the soul in pain—everything seems right enough, but none of it makes one feel any better. However, Hillman kept mentioning “the images,” and this puzzled me. I supposed he meant the pictures in dreams, but this felt incomplete, in the same way Hillman’s whole effort, despite its brilliance, lacked some crucial efficacy, like out-of-date medication—perhaps even like the prodigious flow of J&B and Johnnie Walker I’d been purchasing the last few months under the discreet liquid eyes of the East Indian convenience market manager and his sari-clad mother seated beside the newspaper racks. I let Hillman’s book go idle, but the idea of pictures stayed with me, and as the summer came along, I thought I might go to Southern California to visit my mother and take some photos.

MY FIRST CALIFORNIA neighborhood, an area of apartment houses near the beach where my parents and I lived from 1953 to 1958, had always drawn me in a powerful way. We moved out of the apartments to a house in a subdivision three quarters of a mile off, where my mother still lived at this time, but my trips south would always include a visit to those older, beach-shabby but somehow luminous and magnetic blocks. There at the old apartment was my bedroom window, looking out onto the quiet street as it always had, the palm trees, the ocean just beyond at the end of the block with its same steady sound and light. I could imagine my younger self in there still, reading, painstakingly assembling a model plane in the perfect, breathing silence of the past. I could give him bits of lyrics, maybe “Cupid, draw back your bow,” or “I’m painting it blue,” or even the Nat King Cole show from a distant room that would enfold my small mental cutout into its own depth like a View-Master or pop-up book, and yet I could never will this figure to look up or speak.

Occasionally, I’d feel myself break through the present to something deeper, or perhaps “fall through” is a better figure: on my rambles I might be overwhelmed with a sudden sadness, a primal ache spread wide like noise between distant stations on the radio, or the sound of surf at night. This I understood in some way to be a truth of childhood. I never knew when this uncanny visit might come, and despite often badly needing assurance that the flat and denatured present was not the world’s last answer to whatever my question was, such glimpses could never be willed. But when they came, they came with force: pedaling over my old school grounds one day, I rolled idly toward a rusty backstop where we used to play ball only to feel my whole body start to shake with some ancient emotion; it was all I could do to keep my balance. All through this period the precinct of the apartments continued to exert its gravity until I finally had a dream in which I gazed down on the apartment from above, filled with the uncanny knowledge that “here the work would continue.”

But of course a lot of time had passed—forty years. This seemed a long while to be obsessing over a worn-out apartment house. My generation had no shortage of narcissists fretting over their supposedly bad childhoods—not bad in the sense of violent, hungry, or poor, but as somehow not leading to a happy adulthood, a far less certain indictment. So I was a skeptical pilgrim. As befits soul work, signs and portents accompanied the enterprise. Once, seeing a new vacancy sign outside the apartment, I got the idea of passing myself off as a prospective renter in order to get inside—the interior spaces, I was sure, would act on me like the bike ride across the playground, only much better, setting off whole depth charges of forgotten feeling. These transports I would somehow hide from the manager as I went from room to room, ad-libbing a cover story. But when I finally worked up courage to pick up the phone for an appointment, my ear was blasted by a shrill howling, neither computer nor fax but a banshee wail I’d never heard before (or since), warning me off. Another time, again on my bike, I saw that not only was the very apartment we had occupied vacant, but that someone was inside cleaning it. With a rising sense of good fortune I dropped the bike in the ivy front yard and went to the screen door. “Hello,” I called to the woman vacuuming the living room, “I used to live here. Would it be OK if I looked around?” The woman briefly surveyed me, eager, large, bearded, sweating, wearing grimy bike gloves, and sensibly answered, “No.”

So later I began to take pictures. Photographer friends at the community college where I worked had taught me an old-fashioned black-and-white technique that seemed intriguing. Mostly I was hoping to make an image that would remind me of the Folkways album covers I had loved in high school, those post–Walker Evans photos of weathered doorways and played-out guitars filled with nostalgia and Americana. But the moment I set up the camera and tripod in the old neighborhood and saw these scenes from my past through a viewfinder, I felt a thrill that was a surprising ownership, a bringing to light, an alchemy that could turn a brooding sorrow into an artifact of reflection. Standing over the camera in the beach overcast early in the mornings and going through the somewhat arcane process of metering to accommodate such slow film often felt like a daring, righteous theft punctuated with a shutter click. I would hurry from spot to spot, muttering to myself with eye screwed to the viewfinder, nervous that an apartment resident might catch me: one by one I felt I was freeing objects and places from some drowsing captivity—the mailbox, the incinerator, the porch, the stairs.

Freud seemed to have felt that memory was a stratum in the mind where our pasts lay perfectly preserved, funerary objects in the burial chambers of recall, but as my pictures accumulated, this came to feel like an overly optimistic theory of the mind’s ability to stabilize the past. Poring over contact prints or making enlargements, I knew each revisiting of memory was as much creation as re-creation. Though the photos might make a sort of language for re-speaking the past, this was a tongue in which metaphor held priority over name.

An only child, I was already well acquainted with tropes of loneliness—the compulsive blank gaze at walls, window boxes, sea light, and the desert pleasure of empty sights and sounds. These spaces began to show up in the photos from the beginning. I felt drawn to child’s-eye views, and to surfaces that, like the suburbs themselves, seemed “blank” at first glance but on which could be seen a subtle patina of history as well, a trace of lost time within which some sort of answer to the present might wait.

I FOUND I took many pictures of blind windows, pulled to these voyeur’s locales where the desire to see within was suspended in the surface interest of the window’s texture itself, glass, muntins, frame, sashes, cracked putty, salt-corroded aluminum, the flawed stucco at the window’s edge—I began to imagine all these as figuring the ways we have of looking within and back. I felt drawn to doors and fences subject to the same decay against which they defended, as well as architectural details, walls touched with the circular rub of an absent plant, or the patina of repainting. There were plants as well, succulents, bamboos, grasses, palms, and pittosporums in subdivisions and vacant lots, once the subject of an orderly agenda but now vestigial, a scrim between past and present. There could also be images of power and understanding sent underground, ordering systems grown into crude networks, textured with time; I made pictures of taps, utilities, electric meters, wires, fixtures, and other traces of life’s galvanic body rising into the light, perhaps like the dreams we later recall and reconstruct, now condensed into daylight systems of value, of what we need to have been so, and what instead seems to be.

It was important that these images be unpopulated. It was objects I wanted, and the “tears of things.” Church icons, their historical roots in Egyptian funerary portraits, radiated a stillness that was a sign of their subjects having passed over, and the sacred nature of the image was a quality of that unreachable stillness. Now when I opened the shutter to let the morning’s gray light settle over the film emulsion, the shards and surfaces of my neighborhood seemed to take on a similar poise.

I WAS STAYING with Mother, back in my old room. This meant a lot of listening. Everyone told stories in our family, and many were delightful. However, no one was quite the tale-teller Mother had become over the years. Conscious as she was of dominating the moment with her own narratives, Mother greeted stories from others with extravagant praise and laughter, but the truth was that this was not a person who listened so much as one who waited to talk, and in fact waited painfully for the smallest appearance of that momentarily unclaimed silence she badly needed to fill. Father had long learned to stay out of her way, and saved rollicking tales of his Appalachian boyhood for his brothers and hometown friends—unless Mother felt that one of his stories was needed at the moment, when she became a relentless recruiter. Then his eyes would blink nervously and his gaze fall off to the side as he would launch awkwardly into the now deeply curtailed narrative while she guided him with corrections and reminders toward the desired punch line, which she would then repeat like a roofer driving home a nail.

Mother’s stories were never improvisatory or searching; in the theology of narrative, she was a firm predestinarian. Once a story was launched, at its first words the veteran hearer knew his fate ineluctably for the next few minutes, for the tales never varied in incident, detail, point of view, or conclusion. And it would have taken a bolder Lollard than Father or me to interrupt this ritual; the fixed brightness in Mother’s eye and the tiny but unmistakable tremor of emotion in her voice gave strong warning that her moment was not to be tampered with. In the usual family way, I had managed to grow up knowing all this without really knowing it, but after being married, at get-togethers and awkward “nice” evenings out with the parents, perhaps seated beside my wife at the Velvet Turtle in the Riviera Village with its oversized, padded menus and prime rib cart wheeled to the table, a more distant, anthropological view of the family folkways became all too clear while Mother filled the silences from her repertoire and Father smoothed his tie end as he gazed into a middle distance.

The stories fell into cycles, of family, employment, childhood, or travel:

What Father had said on arriving in Lincoln, Nebraska, after driving through the Missouri floods of 1947;

What her brother-in-law had said at the bridge game in 1955 when Mother trumped Father’s ace, and what Father had said to the brother-in-law;

What good advice she had given me when I was four;

What good advice she had given me when I was twenty-four;

What supposedly funny thing Father had said to her on their first date while they were watching Rhapsody in Blue, and how this should have put her on her guard;

How her teachers had mispronounced her first name and how she had corrected them and how they had tried to make her write right-handed and turned her paper so she wouldn’t write over the top of the paper with her left hand to compensate, and how she would change the paper back as soon as the teacher walked away;

How she pouted because she couldn’t learn to ice skate like the other kids, so her parents drove her to the pond in Lincoln on a freezing winter afternoon, left her there with her skates, and drove off;

What Mother had said to her cousin Jane on the day in 1972 when Jane’s doctor had told Mother but had not told Jane that Jane’s cancer was terminal;

How her father, street-cleaning supervisor of Nebraska’s capital, had known when to call out the snow plow crews by watching the density of the flakes as they blew past the streetlight outside their house on P Street;

How on a day in 1958, in her bed in Lincoln, her mother had made a groaning sound that caused her husband to believe she had indigestion, but instead she had passed away so that this groan was the final utterance of a woman who in her life had been full of funny tales, saws, jokes, comic poems, and quaint sayings.

There was even an entire cycle dedicated just to her Uncle Harve:

How many of Uncle Harve’s needlepoints were hanging on the walls of our home;

How during her childhood Harvey had come every summer from Philadelphia to visit;

How his clothes were immaculate and beautifully tailored;

How he purchased his needlepoint supplies exclusively at Wanamaker’s;

How he freehand stitched his designs of birds and Italianate villas and flowers straight onto the canvas;

How her mother sweated hand-cranking ice cream on the back porch for him in the stifling Midwestern summers, the drops rolling down her face as she packed handfuls of rock salt on the ice and forced the stubborn paddles through the slowly freezing cream so that he could absently extend a hand for the bowl without saying thank you as he sat in the shade doing needlework;

How her father had called Uncle Harvey “an old woman.”

MOTHER’S NARRATIVES WERE rigid as hymns, and the central mystery they celebrated was the unwavering primacy of her point of view, as well as the chaos that would follow should this bulwark fail. After I began making pictures, I felt like I’d found a way in past the liturgy. Before the photo project, visiting the old haunts could well mean a ride on the dragon’s tail of blue-black depression by day three. Now it began to be a little easier.

By 1996, Father had been dead for three years and Mother, in her seventies, was living on her own in her house in Redondo Beach. The sixty-seven-dollar-a-month FHA mortgage payments she and Father had begun in 1957 had come to an end in 1987, and the house was in the clear and appreciating at a manic rate. Almost every morning she walked along the ocean, taking in the breeze and counting dolphins cresting out of the grayish surge, and then drove to the pier where she had coffee with a group of her age and outlook; thus reinforced, she was home by nine and ready to meet the day, calling church and women’s group friends, meeting them for lunch, tending her roses, doing chores, and often going out in the evenings to a church function or concert at a local theater, enjoying Guys and Dolls at the South Bay Civic Light Opera, seated beside her fellow season-ticket holders with whom she had been going to similar functions since the second Eisenhower administration, a long era of good feeling.

Meanwhile, in the northern part of the state, I watched my images float up out of the fix, and gently stacked the negatives in their archive preservers one atop another in a slowly filling Gnosticism of ring binders. I began to see things differently. While I was always conscious of Mother as a lonely widow living on her own—she certainly missed Father—on the other hand, with no one to please besides herself and no one to contradict her, she was flourishing. In fact, enjoying good health, sufficient means, and a wide and solicitous social network, in a locale she loved thick with watchful neighbors who indulged her in every way, she was actually about as happy as she had ever been. Walking her miniature Schnauzer briskly along the Esplanade, carrying his carefully collected droppings in a discreetly opaque Albertson’s bag, decked out in her white Asics walking shoes, cotton sport togs, and L.L. Bean anorak, and greeting an equally cheerful parade of regulars, Mother in these years cut a satisfied figure that would not have been out of place in a photo from a California Public Employees Retirement System brochure.

On one of my early photography expeditions to Redondo, Mother had actually spotted me one morning as I was working. To take advantage of the quiet and the lustrous overcast, I’d leave her house just before sunup, load the tripod into the rear seat of my car, and move along the route I’d planned the day before on scouting walks, trying to expose at least one or two rolls of film before too many folks were up and about. Mother had been returning from the pier past the Presbyterian church, and there I was, a half block away on South Juanita, her son, bearded, overweight, once perhaps a person of some promise but now a childless and unforthcoming freshman composition teacher in his late forties, for some reason pursuing a new activity, hauling a tripod and camera around the neighborhood in which he’d grown up and, at the moment as she was driving past, hunched over and peering through the viewfinder at what seemed to be a pittosporum in a vacant lot.

Back at the house, both of us in the den looking through the LA Times, she related a story from one of the coffee drinkers at the pier, of how this lady knew all about birds and had traveled widely, how she projected an air of authority, of how she spoke somewhat gruffly with her shoulders moving forcefully as she put forward her opinions with an air of self-importance, all of which Mother imitated in voice and body language; but also, as the story went on to its second level, of how despite this spiky surface the woman was a nice person and really did know what she was talking about and so was not a “character,” and what this woman had said to the pleasant Korean owner of the small counter café where they bought their coffee, and what amusing thing he had said back in his broken English. As Father had done, I smiled and nodded in practiced response; in two days I now had this story memorized. Under the nacreous overcast of her morning get-togethers and the anxious pressure of her emerging role as an unattached person, a new colony of small, fixed narratives was forming in Mother like seed pearls. Then she mentioned seeing me. “Oh, you did?” I said. Interruptions in the flow of story were unusual, especially references to me; I had never learned not to be surprised at them, and a little alarmed. “Yes, I was on Avenue D and there you were,” she said, “and I thought: Bless his heart, there he is taking his pictures.”

In the meantime, after months of blank grief, my wife and I began seriously to consider adoption. This meant a kind of surrender, especially on my part, raised as I had been to invest deeply in the mythology of the family tree—a quest the majority of my cousins, I noticed, eschewing children themselves, had not bothered to take up. Bearing a much harder role as the matrix out of which all our hopes would have to materialize, my wife had reached a center of acceptance well before me. Months later, she was still feeling the reluctant ebbing away of the fertility drugs we’d begun injecting in her the fall before, dark tidal pulls of hormone—fabulously expensive hormone—that left her feeling sluggish, alien, out of round, and experimented upon. She was rightly tired of carrying the biological burden.

“I don’t know why she’s not getting pregnant,” one of our doctors had said to me in the early 1980s. He had performed laparoscopic surgery, successfully so he thought, but several months had passed to no avail. Teased and coddled by his big-haired office staff, this was a man who wore cowboy boots and a flashy rodeo buckle around his low-slung belly, and who, in his gruff frontier way, performed painful gas tests in his office without overly worrying about his patients’ discomfort. Still, he was said to be a competent man and an expert surgeon, and in the Northern California town where we had moved, the fertility specialist of choice. His puzzlement only opened the door for more of the magic thinking that afflicts infertile couples, as it does every slow unfolding disaster, the why and what if that won’t go away. It’s all a matter of thinking good thoughts; it’s all a matter of not thinking too much; friends want to loan you the African fertility fetish that has helped friends of friends and distant acquaintances get pregnant; other friends are praying for you—are you receptive? You’re assured that as soon as you make the down payment for the in vitro treatment an embryo will make its appearance, as if irony were a creative force rather than a rhetoric.

Actually, we both had a good idea as to the origin of our troubles—fitting for lovers of cinema, it happened on a rainy afternoon in the early 1970s at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences theater on Wilshire. A young teacher and his even younger girlfriend, we were viewing a rerelease of Chaplin’s Limelight thanks to free tickets from a teacher friend who was also an Academy member, and were comfortably nestled in the green leather seats of the theater just after a visit to our first gynecologist, the referral a friendly tip from another teacher, this one young and female. In the man’s office high above La Brea an hour or two earlier, we’d sat waiting among attractive, well-cared-for women beside a fresh stack of the doctor’s new book, an avuncular sexual guide hoping to rise on the sales charts after the success of the recent, post-puritan best seller Everything You Ever Wanted to Know about Sex but Were Afraid to Ask. The doctor himself was tall, handsome, very charming, and while I lurked uncomfortably in the waiting room, he recommended and put in place an IUD for the young lady.

Only now, two hours or so later, as the screen before us is filled with some incomprehensible Chaplinesque whimsy, beside me in the dark my future wife feels very, very sick, in deep pain and alternating hot and deadly cold. She’s gripping my hand, she’s about to faint, she whispers, and in her grip, quietness, and centered gaze I’m beginning to meet a heretofore hidden Midwestern toughness—like my family, hers has come west from somewhere else carrying a harder, less sun-kissed core. A couple for keeps, I would say now, we rise and excuse ourselves down the row to exit the theater into a light rain. She’s slowly recovering, less pale as we make our way back to Redondo along the wet hissing freeway, the light-streaked beach-cities exit smelling of damp and eucalyptus at the deserted stoplight. The next day another doctor takes the IUD out and tells us all will be well, but as the years go by it’s hard not to believe that the damage has been done, despite our cowboy doctor’s gas tests and surgery and the upbeat encouragement of the fertility clinic staff and the albums in their waiting rooms next to copies of Sports Illustrated and Money and of photos of people just like us with brand-new babies.

Although even to me it seems well past the time to let all this go, like Mother’s indestructible stories, my little mythologies are dying hard. “Maybe,” my wife says one evening four months or so after the miscarriage, with a certain pointed patience in her voice as I’ve been going on yet again, airing my reluctance to venture outside our own beloved gene pool, “maybe we shouldn’t talk about this while we’ve been drinking.” Blinking in a long-awaited sufficiency of shame, I put the Scotch back in the cupboard, and we call the adoption people the next day.

MEANWHILE, TUESDAY NIGHTS in Redondo Mother goes out to eat at the Brewery, a nice two-story bar-bistro in the Riviera Village, only a block from our old apartment—in fact, from the second floor, one can just see the black roofline of the apartment building itself among the jumbled gloom at the bottom of the large money-making rectangle of sunset and palm trees visible from the restaurant balcony. This is not a place Mother would ever venture into on her own, but her across-the-street neighbors F. and D. have been taking her there for years, and now they follow a fond and well-articulated routine into which I’m invited when I’m in town—the brisk walk down the hill to the village, the chattering conversation under the rushing sounds of home-going commuter traffic, and the streetlights coming on in the overcast.

Across the streaming Pacific Coast Highway, the village sidewalks are another decade older than the subdivision we’ve just left, with Ficus and pepper tree roots knuckling through the paving in front of the rectilinear Eames-Ellwood-Neutra-look midcentury shop fronts. F. and D. are probably a dozen years older than I am, sweet and friendly. Great friends of Father, they are now extremely patient with Mother. Their fanatical attachment to garage sales and their garage itself, bulging with years of bargains and purchases, their hobbies and eccentricities—stained glass making, record collecting, beer brewing, and Catholicism—provide Mother with a rich horde of story material.

Seated at our table by a tall, handsome girl in black leggings—“How are you guys?”—we have our drinks and peruse the menu. Everything, Mother assures me, is huge, too much to eat at once; everyone but me, it is assumed, whose extra pounds advertise my inability to hold to a sensible portion, will be carrying plastic containers of smoked chicken pasta back up the hill.

F. now regales me with his recent garage-sale finds, AR two-way speakers in mid-sixties walnut enclosures, an Altec Lansing preamp, and Dynaco woofers that heft like exercise gear, treasures over which a shockingly small amount of money has changed hands. Even though F. tends to go on a little, I always find this subject soothing: here are my idyllic 1950s moments spent with my beloved Uncle Bob, maker of Heathkits and installer of an endlessly fascinating Garrard turntable on its pullout base in the cabinet above his records, Big Tiny Little, Andre Kostelanetz, and Jackie Gleason’s Music, Martinis, and Memories. He and his wife Nancy, Father’s sister—chic, indulgent, and childless—lived up the hill from here in the Hollywood Riviera with a view of the basin. Both are gone now, but the fogs of the village and the palms and the cars winding down the French-curved postwar suburban streets and the sighing ocean to the barely reddened west are the same while F.’s litany of midcentury hi-fi, of Fisher and McIntosh, of the quest for the Spartan circuit, the straight wire with gain, the supreme fidelity of the linear, have all dropped me into some quietly helpful dream.

Sensing a lull, Mother reprises this morning’s pier story with full gestures, then tells a favorite about F. at the Gardena swap meet, then painstakingly recreates yet again the moment that occurred forty years earlier in the apartment a block west of where we sit when at the family bridge party she trumped Father’s ace and their overbearing opponent, unwittingly condemning himself to a lifetime of playing this unsympathetic role, loudly announced her gaffe so that all the tables could hear. Then Father gallantly replied, in his own father’s quiet, deadpan style, “Susie can trump my ace anytime she wants.” The silence that follows this punch line is a wholly owned subsidiary of Mother’s ancient woe; there’s a tremulous pause inviting us to contemplate but never comfort the scraped-out hollow of her unredeemable loss and her poverty. In the caesura, as people learn to do, F. and D. have settled into a familiar, lightly smiling stillness. “Well, he was quite a fellow,” D. ventures as the food arrives. “Oh my goodness, the size,” says Mother, regarding with asperity the heaping portion set before her.

To my surprise, after this performance, I am feeling pretty well, which has not always been the case. Taking pictures has apparently had some good if obscure effect. The muteness of the images, and the watchful quality of those I feel are most successful, give me a feeling that as regards Mother’s long narrative practice, the photos are anti-stories. I sensed in the mute and inexplicable calm of those images I liked best a small chamber of air against this narrative avalanche and homage to the life long reticence Father and I had come to learn.

I can also sense growing out of the future the appointment we have made at the adoption center in a month’s time, and for another, can feel packed for my drive north tomorrow the rolls of exposed film exerting their quiet promise. “Meter to the black,” I was instructed, “then back off two f-stops and let the highlights take care of themselves.” At 25 ASA stepped down to 12, the tripod mustn’t tremble, the mirror has to stay locked in the up position, you have to stand to one side and trigger the shutter with a remote release as if waiting for that comic flash of powder atop an old Speed Graphic. But those miniature incendiaries never come; instead the subjects of your gaze remain mute during their sixtieth-, or thirtieth-, or quarter-, or half-, or even whole-second-long capture before the shutter snaps to a close. Then those Lords of Life are left to the breathing world, while in your camera lie waiting sonograms in gray scale of the subtle body of the past.