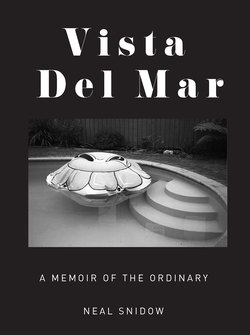

Читать книгу Vista Del Mar - Neal Snidow - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 The Birth Mother Letter

ONCE MY EYES adjusted I could see the images darken in the trays. Anyone who has developed pictures knows this pleasure, the image rising slowly out of the ghostly squares rocking in their fluid. At first I set up trays and an enlarger in the laundry room and spread cut-up garbage bags over the door cracks, but later I moved the whole operation into the cabin that sat in decay twenty feet off the back porch. We had a baby in the house now, and limiting access to washer and dryer for any length of time was not a good idea. Reluctantly as always, I went back into the mouldering space of the cabin and hung black plastic over the windows, put the enlarger on what had been the kitchen counter, covered the sink with a door blank, arranged the trays over its surface, laid a trickling garden hose in the rinse tray, ran its suction drain into the bottom of the old sink, cleaned some house screens to set up as drying racks, and started to make prints.

Twenty years before, we’d sold our house in Redondo and moved to Northern California in one of those events that, like ground shifting along a fault, just seem to occur; I certainly can’t recall ever supplying a friend, relative, or even myself with a coherent reason for this move except that it seemed the thing to do at the time. I thought I knew one thing, at least: having finished a first novel and begun work on a second, I wasn’t going to teach high school English again, which despite its rewards was an exhausting job that ate at a person’s creative core and demanded the soul’s full engagement. I needed, I thought, a more pedestrian job, a struggling writer’s job that would bring in money but leave something left to discover at the end of the day. Once we’d bought the cabin, over my typewriter in the midcentury travel trailer I used as an office, I pinned Charles Reznikoff’s somber and beautiful poem to the paneling:

After I had worked all day at what I earn my living

I was tired. Now my own work has lost another day,

I thought, but began slowly,

and slowly my strength came back to me.

Surely, the tide comes in twice a day.

Despite whatever faith I might have in my diurnal energies, springing cash out of our Southern California house sale seemed to have given us a dangerous sense of freedom. On the drive north this turned to an unpleasant, floating nausea as I imagined myself waiting tables, selling stereos, manning a rental-car desk, tutoring, directing traffic with a road crew, driving a “Wide Load” car, or handling baggage at a local airport. No matter with what brio I saw myself in these roles, they seemed frightening; I really might be too anxious a person for such hustle and bricolage. A couple of years later, only somewhat more firmly rooted, these drifting days came rushing back as I struggled through one of Richard Rorty’s books in which he uses as inspiration and pennant for his skeptical read of the human condition verses from Measure for Measure:

But man, proud man,

Drest in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he’s most assured,

His glassy essence, like an angry ape,

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As make the angels weep.

How well I knew that irritable primate, his glassy essence, and those snuffling angels as we rode along the interstate reeling in the vertigo of open-endedness, looking for a place to live with neither job nor house as an anchor. Hadn’t I said good-bye to my beloved beach just an hour before we struck north? I needed suddenly to drive up to one of the empty stretches around Twentieth Street in Manhattan, walk across the sand, and dive in one last time as a native, a local, one who belonged, floating under and looking up at the wave, at its glassy essence, its clear and glaucous light passing over and gone.

After this drift, it felt soothing to interview for a part-time teaching job at the university campus in the town near where we’d decided to locate. The tall, tweedy, and slightly louche English department chair elaborately raised his eyebrows at me as I explained my situation. “God, that’s gutsy,” he cried. A then struggling but now famous writer had worked at the college some years before, and the chairman had gone out of his way to help that writer, loaned him the keys to his office to work on weekends while the struggling young writer’s house was awash in toddlers; there was precedent for fools such as I. He also sympathized with what had to be the culture shock of moving to a rural backwater after life in the City of Angels. He and his wife had come to the area from a large university town back east and knew what this was like. “I mean when we shopped back there for kitchen cabinets,” he confided, “there was cherry, there was hickory, there was butternut. And here they’re showing us particleboard? I said, ‘Oh my God.’” I, he pronounced, was a shoo-in; anyone as kindred a spirit could expect a class in the fall. However, this turned out only to be his manner, once sympathetically aroused finding it hard to say no, and no class materialized.

In the meantime my wife had found a job. She got up early, put on whites, donned a hairnet, and cooked in a convalescent hospital kitchen while I sat home at the typewriter trying to adjust my marine-layered body to the inland valley heat and keep the creative flow going. “The artist is a brute,” said Flaubert. I supposed I felt artistic enough as the pages stacked up, but not nearly enough of a brute to feel comfortable as my cheerful wife came through the door in her white crew shoes, fragrant with rolled turkey roast and gravy. I can at least substitute teach, I thought, and went to the local high school district office to put my name on the list, a process I knew well since Mother’s job as a principal’s secretary had for years involved taking early-morning calls from sick teachers and calling subs from the much scratched and notated palimpsest of the master list that sat by our phone. “Oh, there’s a full-time English opening,” said the secretary, even though it was the second week of the semester. “You should apply.” Two days later I was standing in front of a classroom of adolescents listening to my voice echo in the room, appalled as I took in their brittle glances, their bright unsympathetic eyes, and their familiar, sullen need. I wondered what in the world had happened; but the day before, out jogging after getting the phone call that I’d been hired and now had a paycheck and a place to go every day, I found my arms in the air as a voice broke out of me: “Thank God!”

Just before this we’d bought the cabin, the cabin that eventually became the darkroom. This was literally a cabin, seventeen by seventeen with a ladder to a sleeping loft, woodstove and galley downstairs, an outside bathhouse with toilet, shower, outdoor sink, and sauna, two more usable outbuildings for office and guest room—the sort of place to make one’s parents weep. It sat on a small diamond of land inside sixty acres or so of undeveloped woods, Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, cedars, and oaks—very pretty, cozy, bucolic, its purchase clearly the decision of people with no judgment whatever. Friends and relatives were patient, strenuously simulating enthusiasm as we showed them around and then rolling their eyes in their cars on the way home. As the years went by the cabin also made us wonder: was the elusive nature of pregnancy a response to this unsuitably small nest? Later we added land to the lot and built a house, but the cabin was still there.

Pioneers and exiles in the woods, early 1980s

At the turn of the century, the tiny, lost community of which the dwelling site had first been a part had swollen to ten thousand souls on turpentine and mining; when those bubbles burst, the ridge town sank back on itself and now was a few houses and holdings on a gnarled finger of land cupped around the south bank of Butte Creek Canyon, three miles across and at our elevation twenty-five hundred feet deep, cut wide by the ancient waters pouring from the high lakes another three thousand feet up the mountain. Deer strolled coolly about, ears flipping as they devoured whatever we tried to plant. Bear and mountain lion roamed more discreetly, and Steller’s jays racketed in the trees. On “My November Guest” sorts of days, with clouds drifting up the canyon and hovering over the treetops, backlit like gleaming zeppelins in the western light and then darkening into thunder showers, the woodstove smelled of burning cedar and the window squares filled with a soft, graying green while thunder made a deep pedal tone across the ridge back.

By the time the adoption went through, however, these cozy days were long past, and the cabin itself was an embarrassing outbuilding slowly but surely sinking back into the ridge from which it had come. “You lived in this?” people said, including the social worker from the adoption agency. Now it became my photo studio—inside it, pictures came up out of the dark.

We’d eventually found an agency that handled “open adoptions,” in which birth mothers made contact and then partnerships with prospective adoptive parents. Agency counselors and social workers then led both partners through the legal and emotional reefs and shoals of these complicated waters to the completion of the adoption process. Once an adopting couple had paid a fee and attended a two-day workshop in the Bay Area community where the agency had its main office, a couple constructed a “birth mother letter,” a combination of dwelling, advertisement, and beseeching in words and pictures that went into a thick volume called the “birth mother book.” Expectant young women for whom an “open adoption” seemed the best option perused these books, imagining the child they carried living out her life with the people on the pages. If they saw a couple with whom they “felt a connection,” they could contact them, and if the initial contact went well, could go on to make an agreement with the couple to give the child over to them for adoption at birth. It didn’t bear too much thinking about, really—and there were many times during the process that I found myself wishing fervently for the neat discretion of some sort of Dickensian arrangement in which, fees having changed hands in a leathered office, a thinly smiling lawyer would advance toward us carrying a bundled child, no questions asked.

Instead, we followed the agency guidelines and wrote our letter. Hard at work trying to describe myself in such a way that a young pregnant woman would want to entrust her child to me, I consoled myself by recalling Delmore Schwartz’s short story “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” in which the dreaming narrator watches in horror a film of his parents’ courtship which will one day produce an awful marriage which will in turn produce the story’s unbearably unhappy author. It reminded me of one of Mother’s favorite stories, of how she’d met this handsome serviceman on the train to Kansas City, Father of course, and how they’d struck up a conversation as he helped her adjust her seat. I’d been in enough therapy to learn to distrust triumphalist readings of moments like this. Fitting our letter into a transparent sleeve and clicking it into place in the ring binder where it would wait for a pregnant girl in one of the several states where the agency operated to flip through the pages and get an inkling, an intuition, a murmur of connection to us, might not be an improvement on the usual way of forming families, but on the other hand might not be much worse.

Cheerful self-advertisement in the birth mother letter

Earlier, at the first orientation, seated on folding chairs in a conference room with the other hopeful adopters, before the meeting even started, we’d been caught up in an epiphany that seemed to strike all of us at the same time: finally here were people who understood. Here were people who knew what it was to want children, who watched the years drift past in twenty-eight-day increments, earnest “aunts,” “uncles,” and godparents who bought toys for their friends’ new babies and faithfully went to birthdays and baptisms and made quilts and sent cards and gave congratulations. Just feeling this knowledge and deep mourning move silently across the room into every person was enough. No one spoke, and then one young woman simply began to weep. After that, it felt reasonable enough that a young pregnant woman would look through a book and pick out the parents of her child.

However, six months after the orientation, no one had contacted us. Our optimism started to flag; clearly, there was something terribly wrong with our cheerful, loving self-advertisement, and thus with us. We felt back in the grip of the old familiar cycle of failure, and one evening came home in an especially dark mood. It was the anniversary to the day of losing the in vitro pregnancy. We’d been to a movie, but that had only postponed the inevitable, and now we were back in our empty house. My wife had begun quietly to cry; we both felt dark and empty. But turning the unlit corner into the dining room, I could see that the phone message was blinking. This would be a relative, I thought, reaching down, or someone from work with a problem to solve. While my wife put her coat away, I pushed the message button, only to hear a young, unfamiliar, tentative female voice sound in the quiet room: “Hi—I saw your birth mother letter and wanted to talk.” The message went on and gave a name and number. My wife came toward the phone, wide-eyed. “Oh my God,” I said. I pulled the chair back, sat her down—this was her moment—and went to get her a box of tissues. Then, while she dialed and began to speak, I went in another room and sat very still.