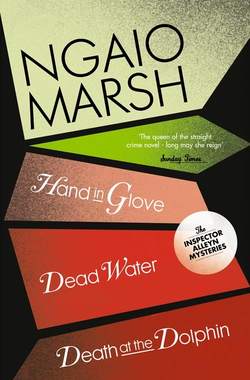

Читать книгу Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 8: Death at the Dolphin, Hand in Glove, Dead Water - Ngaio Marsh, Stella Duffy - Страница 24

CHAPTER 4 Alleyn

Оглавление‘There you are,’ said Superintendent Williams. ‘That’s the whole story and those are the local people involved. Or not involved, of course, as the case may be. Now, the way I looked at it was this. It was odds on we’d have to call you people in anyway, so why muck about ourselves and let the case go cold on you? I don’t say we wouldn’t have liked to go it alone, but we’re too damned busy and a damn’ sight too understaffed. So I rang the Yard as soon as it broke.’

‘The procedure,’ Alleyn said dryly, ‘is as welcome as it’s unusual. We couldn’t be more obliged, could we, Fox?’

‘Very helpful and clear-sighted, Super,’ Inspector Fox agreed with great heartiness.

They were driving from the Little Codling constabulary to Green Lane. The time was ten o’clock. The village looked decorous and rather pretty in the spring sunshine. Miss Cartell’s Austrian maid was shaking mats in the garden. The postman was going his rounds. Mr Period’s house, as far as it could be seen from the road, showed no signs of disturbance. At first sight, the only hint of there being anything unusual toward, might have been given by a group of three labourers who stood near a crane truck at the corner, staring at their boots and talking to the driver. There was something guarded and uneasy in their manner. One of them looked angry.

A close observer might have noticed that in several houses round the green, people who stood back from their windows, were watching the car as it approached the lane. The postman checked his bicycle and with one foot on the ground, also watched. George Copper stood on the path outside his corner garage and was joined by two women, a youth and three small boys. They, too, were watching. The women’s hands moved furtively across their mouths.

‘The village has got on to it,’ Superintendent Williams observed. ‘Here we are, Alleyn.’

They turned into the lane. It had been cordoned off with a rope slung between iron stakes and a ‘Detour’ sign in front. The ditch began at some distance from the corner and was defined on its inner border by neatly heaped-up soil and on its outer by a row of heavy drain-pipes laid end to end. There was a gap in this row, opposite Mr Period’s gate, and a single drain-pipe on the far side of the ditch.

One of the workmen made an opening for the car and it pulled up beyond the truck.

Two hundred yards away, by the side gate into Mr Period’s garden, Sergeant Raikes waited self-consciously by a disorderly collection of planks, tools, a twelve-foot steel ladder, and an all too eloquent shape covered by a tarpaulin. Nearby, on the far side of the lane, was another car. Its occupant got out and advanced: a middle-aged, formally dressed man with well-kept hands.

‘Doctor Elekton, our divisional surgeon,’ Superintendent Williams said, and completed the introductions.

‘Unpleasant business, this,’ Dr Elekton said. ‘Very unpleasant. I don’t know what you’re going to think.’

‘Shall we have a look?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Bear a hand, Sergeant,’ said Williams. ‘Keep it screened from the green, we’d better.’

‘I’ll move my car across,’ Dr Elekton said.

He did so. Raikes and Williams released the tarpaulin and presently raised it. Alleyn being particular in such details, he and Fox took their hats off and so, after a surprised glance at them, did Dr Elekton.

The body of Mr Cartell lay on its back, not tidily. It was wet with mud and water, and marked about the head with blood. The face, shrouded in a dark and glistening mask, was unrecognizable, the thin hair clotted and dirty. It was clothed in a dressing-gown, shirt and trousers, all of them stained and disordered. On the feet were black socks and red leather slippers. One hand was clenched about a clod of earth. Thin trickles of muddy water had oozed between the fingers.

Alleyn knelt beside it without touching it. He looked incongruous. Not his hands, his head, nor, for that matter, his clothes, suggested his occupation. If Mr Cartell had been a rare edition of any subject other than death, his body would have seemed a more appropriate object for Alleyn’s fastidious consideration.

After a pause he replaced the tarpaulin, rose, and keeping on the hard surface of the lane, stared down into the drain.

‘Well,’ he said. ‘And he was found below, there?’ His very deep, clear voice struck loudly across the silence.

‘Straight down from where they’ve put him. On his face. With the drain-pipe on top of him.’

‘Yes. I see.’

‘They thought he might be alive. So they got him out of it. They had a job,’ said Superintendent Williams. ‘Had to use the gear on the truck.’

‘He was like this when you saw him, Doctor Elekton?’

‘Yes. There are multiple injuries to the skull. I haven’t made an extensive examination. My guess would be, it’s just about held together by the scalp.’

‘Can we have a word with the men?’

Raikes motioned them to come forward and they did so with every sign of reluctance. One, the tallest, carried a piece of rag and he wiped his hands on it continually, as if he had been doing so, unconsciously, for some time.

‘Good morning,’ Alleyn said. ‘You’ve had an unpleasant job on your hands.’

The tall man nodded. One of his mates said: ‘Terrible.’

‘I want you, if you will, to tell me exactly what happened. When did you find him?’

Fox unobtrusively took out his note-book.

‘When we come on the job. Eight o’clock or near after.’

‘You saw him at once?’

‘Not to say there and then, sir,’ the tall man said. He was evidently the foreman. ‘We had a word or two. Nutting out the day’s work, like. Took off our coats. Farther along, back there, we was. You can see where the truck’s parked. There.’

‘Ah, yes. And then?’

‘Then we moved up. And I see the planks are missing that we laid across the drain for a bridge. And one of the pipes gone. So I says: “What the hell’s all this? Who’s been mucking round with them planks and the pipe?” That’s correct, isn’t it?’ He appealed to the others.

‘That’s right,’ they said.

‘It’s like I told you, Mr Raikes. We all told you.’

‘All right, Bill,’ Williams said easily. ‘The superintendent just wants to hear for himself.’

‘If you don’t mind,’ said Alleyn. ‘To get a clear idea, you know. It’s better at first hand.’

The foreman said: ‘It’s not all that pleasant, though, is it? And us chaps have got our responsibility to think of. We left the job like we ought to: everything in order. Planks set. Lamps lit. Everything safe. Now look!’

‘Lamps? I saw some at the ends of the working. Was there one here?’

‘A-course there was. To show the planks. That’s the next thing we notice. It’s gone. Matter of fact they’re all laying in the drain now.’

‘So they are,’ Alleyn said. ‘It’s a thumping great drain you’re digging here, by the way. What is it, a relief outfall sewer or something?’

This evidently made an impression. The foreman said that was exactly what it was and went into a professional exposition.

‘She’s deep,’ he said, ‘she’s as deep as you’ll come across anywhere. Fourteen-be-three she lays and very nasty soil to work, being wet and heavy. One in a thou’ fall. All right. Leaving an open job you take precautions. Lamp. Planks. Notice given. The lot. Which is what we done, and done careful and according. And this is what we find. All right. We see something’s wrong. All right. So I says: “And where’s the bloody lamp?” and I walk up to the edge and look down. And then I seen.’

‘Exactly what?’

The foreman ground the rag between his hands. ‘First go off,’ he said, ‘I notice the pipe, laying down there with a lot of the soil, and then I notice an electric torch -it’s there now.’

‘It’s the deceased’s,’ Williams said. ‘His man recognized it, I thought best to leave it there.’

‘Good. And then?’ Alleyn asked the foreman.

‘Well, I noticed all this, like, and – it’s funny when you come to think of it – I’m just going to blow my top about this pipe, when I kind of realize I’ve been looking at something else. Sticking out, they was, at the end, half sunk in mud. His legs. It didn’t seem real. Like I said to the chaps: “Look, what’s that?” Daft! Because I seen clear enough what it was.’

‘I know.’

‘So we get the truck and go down and clear the pipe and planks out of it. Had to use the crane. The planks are laying there now, where we left them. We slung the pipe up and off him and across to the far bank like. Then we seen more – all there was to see. Sunk, he was. Rammed down, you might say, by the weight. I knew, first go off, he was a goner. Well – the back of his head was enough. But –’ The foreman glared resentfully at Raikes. ‘I don’t give a b– what anyone tells me, you can’t leave a thing like that. You got to see if there’s anything to be done.’

Raikes made a non-committal noise and looked at Alleyn.

‘I think you do, you know, Sergeant,’ Alleyn said and the foreman, gratified, continued:

‘So we got ’im out like you said, sir. It was a very nasty job, what with the depth and the wet and the state he was in. And once out – finish! Gone. No mistake about it. So we give the alarm in the house there and they take a fit of the horrors and fetch the doctor.’

‘Good,’ Alleyn said, ‘couldn’t be clearer. Now, look here. You can see pretty well where he was lying, although, of course, the impression has been trodden out a bit. Unavoidably. Now, the head was about there, I take it, so that he was not directly under the place where the planks had been laid, but at an angle to it. The feet beneath, the head out to the left. The left hand, now. Was it stretched out ahead of him? Like that? With the arm bent? Was the right arm extended – so?’

The foreman and his mates received this with grudging approval. One of the mates said: ‘Dead right, innit?’ and the other: ‘Near enough.’ The foreman blew a faint appreciative whistle.

‘Well,’ Alleyn said, ‘he’s clutching a clod of mud and you can see where the fingers dragged down the side of the ditch, can’t you? All right. Was one plank – how? Half under him or what?’

‘That’s right, sir.’

Superintendent Williams said: ‘You can see where the planks were placed all right, before they fell. Clear as mud, and mud’s the word in this outfit. The ends near the gate were only just balanced on the edge. Look at the marks where they scraped down the side. Bound to give way as soon as he put his weight on them.’

The men broke into an angry expostulation. They’d never left them like that. They’d left them safe: overlapping the bank by a good six inches at each side; a firm bridge.

‘Yes,’ Alleyn said, ‘you can see that, Williams. There are the old marks. Trodden down but there, undoubtedly.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ said the foreman pointedly.

‘Now then, let’s have a look at this lamp,’ Alleyn suggested. Using the ladder, they retrieved it from its bed in the ditch, about two feet above the place where the body had lain. It was smothered in mud but unbroken. The men pointed out an iron stanchion from which it had been suspended. This was uprooted and lying near the edge of the drain.

‘The lamp was lit when you knocked off yesterday, was it?’

‘Same as the others and they was still burning, see, when we come on the job this morning.’

Alleyn murmured: ‘Look at this, Fox.’ He turned the lamp towards Fox who peered into it.

‘Been turned right down,’ he said under his breath. ‘Hard down.’

‘Take charge of it, will you?’

Alleyn rejoined the men. ‘One more point,’ he said. ‘How did you leave the drain-pipe yesterday evening? Was it laid out in that gap, end to end with the others?’

‘That’s right,’ they said.

‘Immediately above the place where the body was found?’

‘That’s correct, sir.’

The foreman looked at his mates and then burst out again with some violence. ‘And if anyone tries to tell you it could be moved be accident you can tell him he ought to get his head read. Them pipes is main sewer pipes. It takes a crane to shift them, the way we’ve left them, and only a lever will roll them in. Now! Try it out on one of the others if you don’t believe me. Try it. That’s all.’

‘I believe you very readily,’ Alleyn said. ‘And I think that’s all we need bother you about at the moment. We’ll get out a written record of everything you’ve told us and ask you to call at the station and look it over. If it’s in order, we’ll want you to sign it. If it’s not, you’ll no doubt help us by putting it right. You’ve acted very properly throughout as I’m sure Mr Williams and Sergeant Raikes will be the first to agree.’

‘There you are,’ Williams said. ‘No complaints.’

Huffily reassured, the men retired.

‘The first thing I’d like to know, Bob,’ Alleyn said, ‘is what the devil’s been going on round this dump? Look at it. You’d think the whole village had been holding May Day revels over it. Women in evening shoes, women in brogues. Men in heavy shoes, men in light shoes, and the whole damn’ mess overtrodden, of course, by working boots. Most of it went on before the event, all of it except the boots, I fancy, but what the hell was it about?’

‘Some sort of daft party,’ Williams said. ‘Cavorting through the village, they were. We’ve had complaints. It was up at the big house, Baynesholme Manor.’

‘One of Lady Bantling’s little frolics,’ Dr Elekton observed dryly. ‘It seems to have ended in a dog-fight. I was called out at two thirty to bandage her husband’s hand. They’d broken up by then.’

‘Can you be talking about Desirée, Lady Bantling?’

‘That’s the lady. The main object of the party was a treasure hunt, I understand.’

‘A hideous curse on it,’ Alleyn said heartily. ‘We’ve about as much hope of disentangling anything useful in the way of footprints as you’d get in a wine press. How long did it go on?’

‘The noise abated before I went to bed,’ Dr Elekton said, ‘which was at twelve. As I’ve mentioned, I was dragged out again.’

‘Well, at least we’ll be able to find out if the planks and lantern were untouched until then. In the meantime we’d better go through the hilarious farce of keeping our own boots off the area under investigation. What’s this? Wait a jiffy.’

He was standing near the end of one of the drain-pipes. It lay across a slight depression that looked as if it had been scooped out. From this he drew a piece of blue letter-paper. Williams looked over his shoulder.

‘Poetry,’ Williams said disgustedly.

The two lines had been amateurishly typed. Alleyn read them aloud.

‘If you don’t know what to do

Think it over in the loo.’

‘Elegant, I must say!’ Dr Elekton ejaculated.

‘That’ll be a clue, no doubt,’ Fox said, and Alleyn gave it to him.

‘I wish the rest of the job was as explicit,’ he remarked.

‘What,’ Williams asked, ‘do you make of it, Alleyn? Any chance of accident?’

‘What do you think yourself?’

‘I’d say, none.’

‘And so would I. Take a look at it. The planks had been dragged forward until the ends were only just supported by the lip of the bank. There’s one print, the deceased’s by the look of it, on the original traces of the planks before they were moved. It suggests that he came through the gate, where the path is hard and hasn’t taken an impression. I think he had his torch in his left hand. He stepped on the trace and then on the planks which gave under him. I should say he pitched forward as he fell, dropping his torch, and one of the planks pitched back, striking him in the face. That’s guesswork, but I think Elekton, that when he’s cleaned up, you’ll find the nose is broken. As he was face down in the mud, the plank seems a possible explanation. All right. The lantern was suspended from an iron stanchion. The stanchion had been driven into the earth at an angle and overhung the edge between the displaced drain-pipe and its neighbour. And, by the way, it seems to have been jammed in twice: there’s a second hole nearby. The lantern would be out of reach for him and he couldn’t have grabbed it. How big is the dog?’

‘What’s that?’ Williams asked, startled.

‘Prints that have escaped the boots of the drain-layers, suggest a large dog.’

‘Pixie,’ said Sergeant Raikes who had been silent for a considerable time.

‘Oh!’ said Superintendent Williams disgustedly. ‘Her.’

‘It’s a dirty great mongrel of a thing, Mr Alleyn,’ Raikes offered. ‘The deceased gentleman called it a boxer. He was in the habit of bringing it out here before he went to bed, which was at one o’clock, regular as clockwork. It’s a noisy brute. There have been,’ Raikes added, sounding a leitmotiv, ‘complaints about Pixie.’

‘Pixie,’ Alleyn said, ‘must be an athletic girl. She jumped the ditch. There are prints if you can sort them out. But have a look at Cartell’s right hand, Elekton, would you?’

Dr Elekton did so. ‘There’s a certain amount of contusion,’ he said, ‘with ridges. And at the edges of the palm, well-defined grooves.’

‘How about a leather leash, jerked tight?’

‘It might well be.’

‘Now the stanchion, Fox.’

Fox leaned over from his position on the hard surface of the lane. He carefully lifted and removed the stanchion. Handling it as if it was some fragile objet d’art, he said: ‘There are traces, Mr Alleyn. Lateral rubbings. Something dragged tight and then pulled away might be the answer.’

‘So it’s at least possible that as Cartell dropped, Pixie jumped the drain. The lead jerked. Pixie got entangled with the stanchion, pulled it loose, freed herself from it and from the hand that had led her, and made off. The lantern fell in the drain. Might be. Where is Pixie, does anyone know?’

‘Shall I inquire at the house?’ Raikes asked.

‘It can wait. All this is the most shameless conjecture, really.’

‘To me,’ Williams said, considering it, ‘it seems likely enough.’

‘It’ll do to go on with. But it doesn’t explain,’ Alleyn said, ‘why the wick in the lantern’s been turned hard off, does it?’

‘Is that a fact!’ Raikes remarked, primly.

‘This stanchion,’ said Williams, who had been looking at it. ‘Have you noticed the lower point? You’d expect it to come out of the soil clean or else dirty all round. But it’s dirty on one side and sort of scraped clean on the other.’

‘You’ll go far in the glorious profession of your choice.’

‘Come off it!’ said Williams, who had done part of his training with Alleyn.

‘Look at the ground where that great walloping pipe was laid out. That, at least, is not entirely obliterated by boots. See the scars in the earth on this side? Slanting hole with a scooped depression on the near side.’

‘What of them?’

‘Try it, Fox.’

Fox, who was holding the stanchion by its top, laid the pointed end delicately in one of the scars. ‘Fits,’ he said. ‘There’s your lever, I reckon.’

‘If so the mud on one side was scraped off on the pipe. Wrap it up and lay it by. The flash and dabs boys will be here any moment now. We’ll have to take casts, Br’er Fox.’

Dr Elekton said: ‘What’s all this about the stanchion?’

‘We’re wondering if it was used as a lever for the drain-pipe. We’re not very likely to find anything on the pipe itself after the rough handling it’s been given, but it’s worth trying.’

He walked to the end of the drain, returned on the far side to the solitary pipe and squatted beside it. Presently he said: ‘There are marks – scrapings – same distance apart, at a guess. I think we’ll find they fill the bill.’

When he rejoined the others, he stood for a moment and surveyed the scene. A capful of wind blew down Green Lane, snatched at a corner of the tarpaulin and caused it to ripple very slightly as if Mr Cartell had stirred. Fox attended to it, tucking it under, with a macabre suggestion of cosiness.

Alleyn said: ‘If ever it behoved us to keep open minds about a case it behoves us to do so over this one. My reading so far, may be worth damn all, but such as it is I’ll make you a present of it. On the surface appearance, it looks to me as though this was a premeditated job and was carried out with the minimum of fancy work. Some time before Cartell tried to cross it, the plank bridge was pulled towards the road side of the drain until the farther ends rested on the extreme edge. The person who did this, then put out the light in the lantern and hid: very likely by lying down on the hard surface alongside one of the pipes. The victim came out with his dog on a leash. He stepped on the bridge which collapsed. He was struck in the face by a plank and stunned. The leash bit into his right hand before it was jerked free. The dog jumped the drain, possibly got itself mixed up with the iron stanchion and, if so, probably dislodged the lantern which fell into the drain. The concealed person came back, used the stanchion as a lever and rolled the drain-pipe into the drain. It fell fourteen feet on his victim and killed him. Ha – hallo! What’s that!’

He leaned forward, peering into the ditch: ‘This looks like something,’ he sighed. ‘Down, I fear, into the depths I go.’

‘I will, sir,’ Fox offered.

‘You keep your great boots out of this,’ Alleyn rejoined cheerfully.

He placed the foot of the steel ladder near the place where the body was found and climbed down it. The drain sweated dank water and smelt sour and disgusting. From where he stood, on the bottom rung, he pulled out his flashlight.

From above they saw him stoop and reach under the plank that rested against the wall.

When he came up he carried something wrapped in his handkerchief. He knelt and laid his improvised parcel on the ground.

‘Look at this,’ he said, and they gathered about him.

He unfolded his handkerchief.

On it lay a gold case, very beautifully worked. It had a jewelled clasp and was smeared with slime.

‘His?’ Williams said.

‘– or somebody else’s? I wonder.’

They stared at it in silence. Alleyn was about to wrap it again when they were startled by a loud, shocking and long-drawn-out howl.

About fifty yards away, sitting in the middle of the lane in an extremely dishevelled condition, with a leash dangling from her collar, was a half-bred boxer bitch, howling lamentably.

‘Pixie,’ said Raikes.