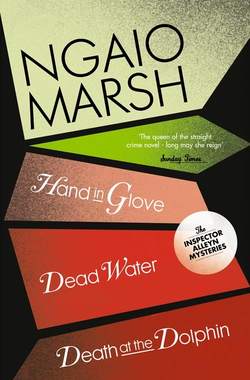

Читать книгу Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 8: Death at the Dolphin, Hand in Glove, Dead Water - Ngaio Marsh, Stella Duffy - Страница 29

II

ОглавлениеWhen Moppett saw Alleyn she clapped her hand to her mouth and eyed him over the top.

‘I’m terribly sorry,’ she said. ‘Auntie C. thought you’d gone.’

She was a dishevelled figure, half-saved by her youth and held together in a negligée that was as unfresh as it was elaborate. ‘Isn’t it frightful,’ she said. ‘Poor Uncle Hal! I can’t believe it!’

Either she was less perturbed than Leonard or several times tougher. He had turned a very ill colour and had jerked cigarette ash across his chest.

‘What the hell are you talking about?’ he said.

‘Didn’t you know?’ Moppett exclaimed and then to Alleyn, ‘haven’t you told him?’

‘Miss Ralston,’ Alleyn said, ‘you have saved me the trouble. It is Miss Ralston, isn’t it?’

‘That’s right. Sorry,’ Moppett went on after a moment, ‘if I’m interrupting something. I’ll sweep myself out, shall I? See you, ducks,’ she added in Cockney to Leonard.

‘Don’t go, if you please,’ said Alleyn. ‘You may be able to help us. Can you tell me where you and Mr Leiss lost Mr Period’s cigarette-case?’

‘No, she can’t,’ Leonard intervened. ‘Because we didn’t. We never had it. We don’t know anything about it.’

Moppett opened her eyes very wide and her mouth slightly. She turned in fairly convincing bewilderment from Leonard to Alleyn.

‘I don’t understand,’ she said. ‘P.P.’s cigarette-case? Do you mean the old one he showed us when we lunched with him?’

‘Yes,’ Alleyn agreed. ‘That’s the one I mean.’

‘Lenny, darling, what did happen to it, do you remember? I know! We left it on the window-sill. Didn’t we? In the dining-room?’

‘Okay. Okay. Like I’ve been telling the Chief God-almighty High Commissioner,’ Leonard said and behind his alarm, his fluctuating style and his near-Americanisms, there flashed up an unrepentant barrow-boy. ‘So, now it’s been found. So what?’

‘It’s been found,’ Alleyn said, ‘in the open drain a few inches from Mr Cartell’s body.’

Leonard seemed to retreat into himself. It was as if he shortened and compressed his defences.

‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ he said. He shot a glance at Moppett. ‘That’s a very nasty suggestion, isn’t it? I don’t get the picture.’

‘The picture will emerge in due course. A minute or two ago,’ Alleyn said, ‘you told me I was welcome to search this room. Do you hold to that?’

Leonard went through the pantomime of inspecting his fingernails but gave it up on finding his hands were unsteady.

‘Naturally,’ he murmured. ‘Like I said. Nothing to hide.’

‘Good. Please don’t go, Miss Ralston,’ Alleyn continued as Moppett showed some sign of doing so. ‘I shan’t be long.’

He had moved over to the wardrobe and opened the door when he felt a touch on his arm. He turned and there was Moppett, smelling of scent, hair and bed, gazing into his face unmistakably palpitating.

‘I won’t go, of course,’ she said opening her eyes very wide, ‘if you don’t want me to but you can see, can’t you, that I’m not actually dressed for the prevailing climate? It’s a trifle chilly, this morning, isn’t it?’

‘I’m sure Mr Leiss will lend you his dressing-gown.’

It was a brocade and velvet affair and lay across the foot of the bed. She put it on.

‘Give us a fag, ducks,’ she said to Leonard.

‘Help yourself.’

She reached for his case. ‘It’s not one of those –?’ she began and then stopped short. ‘Fanks, ducks,’ she said and lit a cigarette, lounging across the bed.

The room grew redolent of Virginian tobacco.

The wardrobe doors were lined with looking-glass. In them Alleyn caught a momentary glimpse of Moppett leaning urgently towards Leonard and of Leonard baring his teeth at her. He mouthed something and closed his hand over her wrist. The cigarette quivered between her fingers. Leonard turned his head as Alleyn moved the door and their images swung out of sight.

Alleyn’s fingers slid into the pockets of Leonard’s check suit, dinner-suit and camel-hair overcoat. They discovered three greasy combs, a pair of wash-leather gloves, a membership card from a Soho club called La Hacienda, a handkerchief, loose change, a pocket-book and finally, in the evening-trousers and the overcoat, the object of their search: strands of cigarette tobacco. He withdrew a thread and sniffed at it. Turkish. The hinges of Mr Period’s case he had noticed, were a bit loose.

He came from behind the wardrobe door with the garments in question over his arm. Moppett, who now had her feet up, exclaimed with a fair show of gaiety: ‘Look, Face, he’s going to valet you.’

Alleyn said: ‘I’d like to borrow these things for the moment. I’ll give you a receipt, of course.’

‘Like hell you will,’ Leonard ejaculated.

‘If you object, I can apply for a search-warrant.’

‘Darling, don’t be bloody-minded,’ Moppett said. ‘After all, what does it matter?’

‘It’s the principle of the thing,’ Leonard mumbled through bleached lips. ‘That’s what I object to. People break in without a word of warning and start talking about bodies and – and –’

‘And false pretences. And attempted fraud. And theft,’ Alleyn put in. ‘As you say, it’s the principle of the thing. May I borrow these garments?’

‘Okay. Okay. Okay.’

‘Thank you.’

Alleyn laid the overcoat and dinner-suit across a chair and then went methodically through a suitcase and the drawers of a tallboy: there, wrapped in a sock he came upon a flick-knife. He turned with it in his hand, and found Leonard staring at him.

‘This,’ Alleyn said, ‘is illegal. Where did you get it?’

‘I picked it up,’ Leonard said, ‘in the street. Illegal, is it? Fancy.’

‘I shall take care of it.’

Leonard whispered something to Moppett who laughed immoderately and said: ‘Oh, lord!’ in a manner that contrived to be disproportionately offensive.

Alleyn then sat at a small desk in a corner of the room. He removed Leonard’s pocket-book from his dinner-jacket and examined the contents which embraced five pounds in notes and a photograph of Miss Ralston in the nude. They say that nothing shocks a police officer, but Alleyn found himself scandalized. He listed the contents of the pocket-book and wrote a receipt for them, which he handed, with the pocket-book to Leonard.

‘I don’t expect to be long over this,’ he said. ‘In the meantime I would like a word with you, if you please, Miss Ralston.’

‘What for?’ Leonard interposed quickly, and to Moppett: ‘You don’t have to talk to him.’

‘Darling,’ Moppett said. ‘Manners! And I’ll have you know I’m simply dying to talk to the … Inspector, is it? Or Super? I’m sure it’s Super. Do we withdraw?’

She was stretched across the foot of the bed with her chin in her hands, ‘a lost girl’ Alleyn thought, adopting the Victorian phrase, ‘if ever I saw one’.

He walked over to the window and was rewarded by the sight of Inspector Fox seated in a police car in Miss Cartell’s drive. He looked up. Alleyn made a face at him and crooked a finger. Fox began to climb out of the car.

‘If you don’t mind,’ Alleyn said to Moppett, ‘we’ll move into the passage.’

‘Thrilled to oblige,’ Moppett said. Drawing Leonard’s gown tightly about her she walked round the screen and out of the door.

Alleyn turned to Leonard, ‘I shall have to ask you,’ he said, ‘to stay here for the time being.’

‘It’s not convenient.’

‘Nevertheless you will be well advised to stay. What is your address in London?’

‘Seventy-six Castlereigh Walk, SW14. Though why …’

‘If you return there,’ Alleyn said, ‘you will be kept under observation. Take your choice.’

He followed Moppett into the passage. He found her arranging her back against the wall and her cigarette in the corner of her mouth. Alleyn could hear Mr Fox’s bass voice rumbling downstairs.

‘What can I do for you, Super?’ Moppett asked with the slight smile of the film underworldling.

‘You can stop being an ass,’ he rejoined tartly. ‘I don’t know why I waste time telling you this but if you don’t, you may find yourself in serious trouble. Think that one out, if you can, and stop smirking at me,’ Alleyn said, rounding off what was possibly the most unprofessional speech of his career.

‘Oi!’ said Moppett, ‘who’s in a naughty rage?’

Alleyn heard Miss Cartell’s edgeless voice directing Mr Fox upstairs. He looked over the banister and saw her upturned face, blunt, red and vulnerable. His distaste for Moppett was exacerbated. There she stood, conceited, shifty and complacent as they come, without scruple or compassion. And there, below stairs, was her guardian, wide open to anything this detestable girl liked to hand out to her.

Fox could be heard saying in a comfortable voice: ‘Thank you very much, Miss Cartell. I’ll find my own way.’

‘More force?’ Moppett remarked. ‘Delicious!’

‘This is Inspector Fox,’ Alleyn said as his colleague appeared. He handed Leonard’s dinner-suit and overcoat to Fox. ‘General routine check,’ he said, ‘and I’d like you to witness something I’m going to say to Miss Mary Ralston.’

‘Good afternoon, Miss Ralston,’ Fox said pleasantly. He hung Leonard’s garments over the banister and produced his note-book. The half-smile did not leave Moppett’s face but seemed rather, to remain there by a sort of oversight.

‘Understand this,’ Alleyn continued, speaking to Moppett. ‘We are investigating a capital crime and I have, I believe, proof that last night the cigarette-case in question was in the possession of that unspeakable young man of yours. It was found by Mr Cartell’s body and Mr Cartell has been murdered.’

‘Murdered!’ she said, ‘he hasn’t!’ And then she went very white round the mouth. ‘I can’t believe you,’ she said. ‘People like him don’t get murdered. Why?’

‘For one of the familiar motives,’ Alleyn said. ‘For knowing something damaging about someone else. Or threatening to take action against somebody. Financial troubles. Might be anything.’

‘Auntie Con said it was an accident.’

‘I dare say she didn’t want to upset you.’

‘Bloody dumb of her!’ Moppett said viciously.

‘Obviously you don’t feel the same concern for her. But if you did, in the smallest degree, you would answer my questions truthfully. If you’ve any sense, you’ll do so for your own sake.’

‘Why?’

‘To save yourself from the suspicion of something much more serious than theft.’

She seemed to contract inside Leonard’s dressing-gown. ‘I don’t know what you mean. I don’t know anything about it.’

Alleyn thought: ‘Are these two wretched young no-goods in the fatal line? Is that to be the stale, deadly familiar end?’

He said: ‘If you stole the cigarette-case, or Mr Leiss stole it or you both stole it in collusion, and if, for one reason or another, you dropped it in the ditch last night, you will be well advised to say so.’

‘How do I know that? You’re trying to trap me.’

Alleyn said patiently: ‘Believe me, I’m not concerned to trap the innocent. Nor, at the moment, am I primarily interested in theft.’

‘Then you’re trying to bribe me.’

This observation showing, as it did, a flash of perception, was infuriating.

‘I can neither bribe nor threaten,’ he said. ‘But I can warn you and I do. You’re in a position of great danger. You, personally. Do you know what happens to people who withhold evidence in a case of homicide? Do you know what happens to accessories before the fact, of such a crime? Do you?’

Her face crumpled suddenly, like a child’s, and her enormous shallow eyes overflowed.

‘All right,’ she said. ‘All right. I’ll tell you. But it wasn’t anything. You’ve got it all wrong. It was –’

‘Well?’

‘It was all a mistake,’ Moppett whispered.

The bedroom door opened and Leonard came out in his purple pyjamas.

‘You keep your great big, beautiful trap shut, honey,’ he said. He stood behind Moppett, holding her arms. He really would, Alleyn had time to consider, do rather well in a certain type of film.

‘Mr Leiss,’ he said, ‘will you be kind enough to take yourself out of this.’

But, even as he said it, he knew it was no good. With astonishing virtuosity Moppett, after a single ejaculation of pain and a terrified glance at Leonard, leant back against him, falling abruptly into the role of seductive accessory. The tears still stood in her eyes and her mouth twitched as his fingers bit into her arm. She contrived a smile.

‘Don’t worry, darling,’ she said, rubbing her head against Leonard. ‘I’m not saying a thing.’

‘That’s my girl,’ said Leonard savagely.