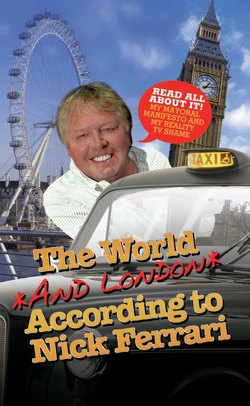

Читать книгу The World and London According to Nick Ferrari - Nick Ferrari - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Myrtle the Fresian: pin-up for the discerning heavy metal fan?

ОглавлениеAs a young man, at just about the time in my life when my secret reading matter really ought to have been the Harrods lingerie catalogue, I used to smuggle a very different publication into my room to read by torchlight after lights out.

There was certainly never a shortage of reading material in my house, simply because my father was a journalist. As a senior executive on the Daily Mirror, he had to keep up to speed with all sorts of subjects, so I could take my pick of any periodical – from the British Medical Journal to Land Rover International – that took my fancy. For me, as a pimply young teenager, there was only ever one choice: Farmers Weekly.

Now I hasten to add that my penchant for Farmers Weekly was not due to the fact that I wanted to cast long, lingering gazes at the centrefold of Myrtle the Fresian; nor were my adolescent loins stirred by the sight of frostbitten old farmers’ wives with green wellies and stout walking canes. On the contrary, whereas my contemporaries found their male hormones were pumped into action by the sight of electric guitars and progressive rock bands with tight leather trousers and long hair, I was entranced by a very different sort of heavy metal. I longed for a tractor and a baling machine. What better way to display my manliness in front of a bevy of country lovelies, who would be putty in my hands once I’d finished shifting several hundredweight of well-rotted manure? How fabulous it would be, I thought, to have a bloody great bit of land up in Leicestershire and to spend my days driving bulldozers and diggers and God knows what else. I’d have a big barn and some Land Rovers. It would be just sensational.

And as I nodded off to sleep over a picture of the latest word in combine harvesters, I would dream of myself as a farmer. I’d have a huge farmhouse, with an enormous, merry blaze in the kitchen fireplace. My buxom, ruddy-faced bride would be sitting at the huge table with a large jug of fresh, pale cream and lots of happy children would be dancing about when I got home from tending the land with my faithful sheepdog, Tag.

Of course, it’s not quite like that.

My passion for farming soon dissipated when I realised that the reality is very different. Farming is about turning out before dawn on a bloody freezing February morning to hulk huge bales of hay around a field on your own when you’re knee-deep in snow; it’s foxes and rats breaking into the henhouse and stealing your chickens and your eggs; it’s impossible vets’ bills – half the value of your mortgage just for them to come up and stick their arms up a cow’s bottom (I know people now who would do that for nothing). I used to think that all I would need to become the perfect farmer was a thorough knowledge of my James Herriot books – surely it would just mean knocking about Yorkshire in an old Austin and having rather genteel little adventures. Little did I know that actually to be a successful farmer you need to have a PhD in organic chemistry so that you can work out exactly which phosphates or nitrates or other fertilisers you should be pouring over your tomatoes.

My point is this: farming is hard. You know that, I know that, the farmers know that. So why is it that farmers are always telling us how hard it is? I think it must be the first thing they learn when they go to farming college. The first two seminars they have to attend must be ‘The Weather: How it Affects Farms and How to Moan About It’ and ‘Government Subsidies: Why They’re Not Enough’. Drive through Oxfordshire or Warwickshire around election time and all you’ll see is tractors parked up in fields saying ‘Blair’s Killing the Farmers’, or declaring that the NFU says no to this and no to that.

I know that the odds are stacked against farmers. And I know that, no matter how much I admire companies such as Tesco, the reason that they are able to sell me my eggs at knockdown prices is because they are squeezing their suppliers – the farmers – as far as they can. In all likelihood they are being paid what they were twenty-five years ago. I have sympathy for their situation, but this is just the way that market forces work. And it’s not all doom and gloom: thanks to the genius of the European Union, we now have this slightly peculiar set-aside scheme whereby farmers are paid to set aside a certain amount of land and not grow anything on it. That way, some Brussels sprout farmer just outside Antwerp will be able to continue growing his veg without any risk of competition. It’s effectively being paid not to work – something rare outside of politics these days. It’s nice lack of work if you can get it.

But farmers don’t see it that way. Maybe it’s because they too used to sit up all night with a torch and copy of Farmers Weekly, imagining how exciting it would be to be able to operate their own heavy machinery. Maybe they did have a penchant for Myrtle the Fresian. And then it didn’t turn out like they thought. Perhaps beneath every whinging farmer, moaning about the weather and his lack of subsidies, there is a heartbreaking tale of broken dreams and lost opportunities. Perhaps we should feel desperately sorry for these people.

But here’s the bottom line: we know it’s hard, but if you don’t like it, you don’t have to do it. Give it all up. Sell your land – it’s probably worth a fortune anyway. Retrain. Become a piano tuner.

At the very least you could flog your James Herriot books. And those back issues of Farmers Weekly might be worth a few quid…