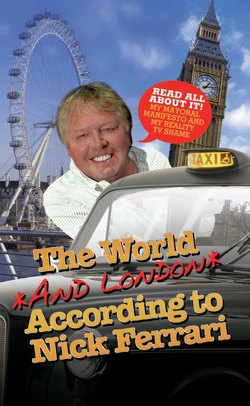

Читать книгу The World and London According to Nick Ferrari - Nick Ferrari - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

How Mogadishu taught me to stop worrying and love my dentist

ОглавлениеIt all started because I had my nose to the stumps.

Perhaps I should explain a little further. In the early 1970s, at the tender age of eleven, I was a member of the worst school cricket team in all of north-west Kent – and that’s really saying something. Our fielding was on the wrong side of dreadful, but it was incomparably brilliant when compared to our batting, which we simply couldn’t do to save our lives. We certainly had no chance of winning a game by dazzling our opponents with our brilliant innings, and so our only hope of success lay in getting the other team out for even fewer runs than our paltry, embarrassing total.

We had – now how can I put this – a fairly strong-minded teacher. In fact, he made Sir Alex Ferguson look like a happy-go-lucky, laid-back, West-coast hippy of a guy. He insisted that I, as wicketkeeper, should crouch literally with my nose against the wickets so that I was on hand for any stumping opportunities that presented themselves if the ball got so much as nicked by the bat. Now this is fine if your opponent is of the more docile and gentle persuasion – a nice slow ball that is likely to bounce anywhere but in the direction of the wicketkeeper; but our bowlers were more in the Freddie Flintoff mould without the talent – long, straight and fast – in which case it was suicidal madness to stand where I was told to put myself. It was really only a matter of time…

I felt sure I had the ball covered. I saw it bounce on the dry pitch. I raised my gloves to make a perfect catch, which is when the full force of my incompetence kicked in: the ball smacked into my mouth, I fell to the ground, and when I come up for air I’m spitting blood and, more crucially, about half my teeth.

So began years and years of painful dentistry. Did I say painful? I mean excruciating torment. Not for me the urbane little trips to the surgery where the worst you had to put up with was that copy of Country Life from 1965 and daft questions about where you’re going on holiday when you’ve got your mouth packed full of scaffolding. That, to me, would have been a walk in the park – well, maybe a slightly strenuous jog in the park, but you get my drift. And back in the bad old days, dentists weren’t anything like as advanced in terms of drugs and techniques as they are now – going to the dentists was a matter of good, old-fashioned horror. You knew how badly it was going to hurt by how much the dentist denied it was going to. ‘You won’t feel this injection a bit,’ they would lie, seconds before sticking a two-foot needle into your gums that felt like it was spearing through your eyeball and into your brain. Gradually I became conditioned to react to these monsters with nothing less than total, blinding fear. At great expense, I had to have an anaesthetist standing by for the simplest operations so that I could be put to sleep and forget my fear. A simple filling, for me, turned into a scene from Holby City.

Back in the dark days of dentistry, ensuring good colour matches of teeth was a hit-and-miss affair, which is why you will never find a picture of Nick Ferrari between the ages of eleven and thirty flashing a toothy grin.

And so, when I was offered a freebie session of teeth-whitening by a dentist who was running a promotion on the radio show, I understandably declined – too scared, you see. It was only when he offered to inject himself with anything he wanted to stick into my gums that I started to have a slightly different view of dentists. Perhaps, after all, they weren’t the psychotic nutters hell-bent on inflicting as much pain on me as possible that I thought they were. And it’s not that I have a sadistic streak, but there was something incredibly comforting about watching this chap stick a needle in his gums – so much so that I didn’t feel a thing as he did the same to me.

As I relaxed in the chair for what I knew was going to be a good long stint, I was handed a pair of high-tech, space-age goggles through which I could watch movies. Having seen how the potential discomfort of others had soothed my fearful soul, I decided that I would be best to choose a movie that depicted violence, pain and the suffering of other people. Black Hawk Down, I decided, was the vehicle for me: whatever dental discomfort I was to go through, it couldn’t be as bad as those poor marines chasing through the war-ravaged streets of Mogadishu.

It worked a treat! I came out with a splendid set of pearly whites and a much improved mental attitude towards my friends the dentists…