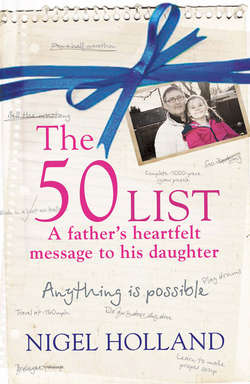

Читать книгу The 50 List – A Father’s Heartfelt Message to his Daughter: Anything Is Possible - Nigel Holland - Страница 16

16 February 2012

ОглавлениеBreaking news: The jigsaw has landed!

Though, to be honest, it’s not the one we’d originally planned on doing. The original, as per my list, was a whopping 5,000-piece job, which we’d borrowed from our friend June Pereira. It was a fine art image, which came with the rather grand title of The Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in his Picture Gallery in Brussels. It looked complicated – which, in jigsaw-land, actually made it easier: the more complex the picture in terms of shapes and tones and colour, the less likely it is to drive you to insanity. It’s the seascapes and landscapes that really vex the committed jigsaw fanatic, which I am not. So it was a no-brainer in that sense.

But I could tell right away that it was going to be impossible: not because it was too hard, even if Ellie found it a little fusty, but because I hadn’t factored in the sheer size of it. It was enormous! Not only would it not fit on the designated coffee table; it wouldn’t fit on the dining table, either, and that was assuming that we’d be happy – which Lisa obviously wasn’t – to have the table out of commission till the thing was finished.

In the end, Ellie and I opted for a 1,000-piece puzzle: a montage of famous steam engines (the Flying Scotsman and the Mallard, among others) which we think Lisa might have bought me years ago and which, as yet unopened, was gathering dust and cobwebs in the loft. And though it was no closer than poor old Leopold to her favoured subject areas of One Direction, One Direction and … let me see now … One Direction, Ellie pronounced it an acceptable replacement.

Doing the jigsaw is one of my more specifically CMT-targeted challenges; and not just for me but for Ellie, too. With CMT it’s not just the lower limb muscle groups that are affected. It attacks the muscles of the arms and hands as well. This obviously has enormous implications for dexterity, and for both Ellie and me muscle wastage, and the accompanying loss of strength, mean our fingers can’t do the things most people take for granted, such as unscrewing bottle tops or lifting heavy items like saucepans, or even something as simple as picking up something off the floor after losing grip on it. For me, with decades of practice at trying to find solutions, it’s all about maintaining independence. Not being able to tie my own laces or put socks on or do up my top shirt button are all things that I have grown to accept are going to be beyond me on some days, because the weakness varies enormously day to day. But I’ve found solutions – electric can opener, electric jar opener, button doer-upper. Sometimes I just work out different ways to do things without any adaptations or devices. It definitely helps focus the mind on what I can do.

For Ellie, though, just starting out on the same journey, the challenges are still exactly that: challenging. We are incredibly lucky in that her school makes every effort to include her in all activities, but she still has to find ways of doing what others can and she can’t. Her dexterity, though better than mine, is already causing her problems, and she’s on the road, just as I was, of having to come to terms with the inevitable: that it’ll be a process of continual deterioration. She is already having to learn to do all her writing on a keyboard – something that’s perhaps not such a problem as it was back in my day, as kids these days, after all, are so competent with computers – but, as with so many things that she can’t do but the rest of her peer group take for granted, it obviously marks her out, and that frustrates her.

As will this jigsaw, I don’t doubt! It’ll frustrate us both. And it’s meant to, since it relies on the ability to pick up really tiny pieces and then slot them into very precise places. Daunting, but, as I hope to prove to Ellie, still achievable. It will just take time and commitment and lots of patience, and at the end of it, boy, will we both feel proud.

But even if we don’t – even if, in the end, it defeats us – Ellie will still have learned a very valuable lesson: that it’s all about giving things a go, having a stab at them. That’s the key to having an exciting and experience-filled life.

Tonight being a Sunday night we decide to get stuck into it, while Lisa is in the kitchen ironing school clothes for Monday morning and Matt and Amy are occupying themselves upstairs.

‘Let’s see who can find the most edges the quickest, shall we?’ I challenge Ellie, as we sit down together on the floor by the coffee table.

I say ‘sit’ but that probably gives the wrong impression. What I actually have to do if I want to be anywhere lower than my wheelchair is ‘transfer’ from it – which all sounds very measured and controlled. Which, of course it is. What I like to call ‘controlled falling’. So I whump down, and immediately see a tactical error: I’m going to have to do this every single time we work on it, since the coffee table is too low for me to do anything from my chair.

But so be it. It’s either that or relocate back to the dining table, and now we’ve started … And, hey, it won’t be for long.

It’s already dark outside, the remaining snow a silvery carpet in the back garden, and sitting here with Ellie, the two of us working at a shared endeavour, feels exactly the right sort of thing to be doing. Something to keep us occupied for the few remaining weeks till spring comes along. And I don’t doubt, looking at the box, that it will take us all of that.

‘Dad, I will, of course,’ Ellie says with conviction.

And, since she’s probably right, I’m not about to argue. Together we carefully pour the pieces into a heap in the centre, taking care not to let any spill onto the carpet, our dog, Berry (named by Ellie – being the youngest, she got her way there), not being fussy when it comes to unexpected potential food gifts. And yes, cardboard does fall into that category. I don’t get much in the way of further conversation after that as Ellie, being Ellie, is too busy trying to beat me. In only minutes she’s amassed an impressive pile in front of her – a pile that I notice is bigger than my own.

‘There,’ she says, as she pushes across a row of four she’s already slotted together, niftily outranking the first corner piece I’ve just unearthed. ‘Can we finish it tonight?’ she adds, lining her handiwork up along her edge of the table. ‘I bet we can, Dad. This is going to be so easy. Easy peasy.’

‘That would be great,’ I agree. ‘But I think it might take a little bit longer.’

Around three weeks, I decide. Three weeks, tops.

* * *

As my condition progressed, so did the wastage of the muscles that had prevented my toes from straightening out as a little boy. So much so that by the time I was eight or nine, I was constantly falling over.

There’s nothing positive about falling over, ever. Though it often made for unexpected entertainment for my classmates, for me it soon became the bane of my existence, as there was never any warning about when I’d next keel over. One minute I’d be walking along happily and the next I’d be flat on my face – literally. There was hardly a day that went by without my sustaining some sort of injury – usually a fat lip or a bloody knee.

I hit the dirt so many times in my formative years that it’s a miracle, looking back, that I’m not a criss-cross of ageing scars, with a nose like that of a battle-hardened prize-fighter. As it is, I got lucky, because my nose is still intact – or perhaps it was the copious application of Germolene and ice packs and plasters that saved me. I only have to get a whiff of that pungent pink ointment to be transported straight back to my primary school playground; to the feel of grit embedded in my palm, the tears welling in my eyes and the suppressed giggles of my mates, who couldn’t stop themselves. The girls, on the other hand, being more sympathetic creatures, would gasp in shock at what had happened, and disapproval, while some teacher or other ran to the rescue.

The reason for this sudden increase in falls was a condition I’d now developed called bilateral foot drop. If you can imagine losing all the muscles that surround your feet and ankles, the resultant floppy appendages – which they’d be, should you try to flap them around a little – will give you an idea of just how infuriating my feet had become. And once a foot doesn’t do what it’s supposed to – i.e. adopt the angle you tell it to – falling over becomes the easiest thing in the world.

But if my pride was wounded by having become someone who could no longer walk properly, that was nothing compared to the alternative I was given: a set of orthotic boots and calipers.

Most kids who grew up in the 1960s will remember calipers, mostly because at that time polio was still a significant problem in the UK. By the beginning of the decade, of course, vaccination had become widespread, but almost everyone knew one kid who clanked around in calipers as a result of having contracted the disease. (I always recall the first time I saw Ian Dury, perhaps the most famous musician of the modern era to be afflicted by polio. I remember thinking two things: what a brilliant bunch of pop songs he’d written, and how did he stop his calipers from squeaking?)

Calipers are designed to support the lower leg, and back then they consisted of a heavy, orthotic ankle boot (which looked very much like the kind of footwear Frankenstein’s monster favoured, on account of its thick sole and bulbous, rounded toe cap), which contained a pin in the heel that connected to a pair of twin steel posts that ran up either side of the leg. These were attached at the top to a leather strap that sat just beneath the knee and could be adjusted to sit snugly around the calf. At the base of the steel bars there was a spring mechanism. This was what would allow my feet to extend, while at the same time, when I lifted my foot from the floor, pulling it back up to prevent foot drop and, therefore, all my falls.

Despite being made to measure, the orthotic boots – which came in black and brown (which was at least one more colour than Henry Ford offered, I suppose) – were extremely uncomfortable. And once fitted up with the calipers (they weren’t the easiest thing to get on and off, either) even more so. Yes, they did their job – they kept my feet at right angles and prevented them from doing the dirty on me – but they also made me walk with a curious, Woodentops-style, stiff-legged gait; so while my older brothers were buying all sorts of trendy footwear in town, I had to endure the indignity of spending my time – in school and out of it – looking like Frankenstein’s monster. At least from the knees down; from the knees up I tried to compensate madly, by adopting a winning smile. Though, given the discomfort, this was probably more of a grimace.

From the day that I donned those boots and calipers I felt different. I was suddenly, and irreversibly, conspicuous. Yes, I could walk around now without fear of falling flat on my face, but with the ugly footwear, the creaky calipers, and the steel bars that fitted attractively to the back of the boots, I now realized that I wasn’t like any other child I knew. While the falls were just a part of me – and, let’s face it, all kids fall over sometimes, some of them often – there was nothing else about me that made me seem any different to any other kid. But now there was. The boots singled me out.

It saddens me now, thinking back to my young self. I was so keen to fit in, so anxious not to let it get to me. But it did. How could it not? Suddenly – and it really did feel as if it happened the very day I first had to don them – my new legwear meant I became a pitiable individual. I was now the boy who was always picked last for a team in football. If I was picked at all, that is, for my ears began ringing with new phrases: ‘Sorry, you can’t play our game because you’re not quick enough,’ ‘Sorry, we’ve got enough now,’ ‘Sorry, we need someone who can kick a ball straight.’

So off I’d trot, trying not to let the hurt I felt show, trying to pretend I had better things to do anyway, trying not to let it get to me. But it did, and my mother could see that all too well. My ‘don’t care’ carapace wasn’t thick enough for me to hide under – not with her.

‘You know what?’ she said one day when she picked me up from school, ‘I was in town earlier, and I was looking in C&A, and they have some really nice new trousers in stock. Very modern.’

And she took me, right away, back into town so that I could try some on. She was right. They were very much the look of the moment, sporting, as they did, the widest flares imaginable. And crucially, as well as being achingly cool, they were wide enough to almost completely hide my calipers. I have a lot to thank the early 1970s fashion extravagances for, I guess. And even more to thank my mum for. I’ll never forget that.

But even though the flares help to boost my flagging self-esteem, now I was in calipers I was officially disabled. No, there wasn’t any official announcement, or formal piece of paper, but there didn’t need to be. As any disabled person will undoubtedly tell you, once you become disabled, people begin to treat you so differently.

Which I suppose is understandable, but even as a child I remember finding it so frustrating that there seemed to be some sort of unspoken perception that the calipers on my legs had somehow affected my brain. That overnight I had suddenly become stupider.

Academically, I had never been at the top of the class, but neither had I been at the bottom. Yet now some teachers (not all: there were some notable exceptions) began to patronize me in a way that was completely unexpected. It was as though I’d broken both my legs and been fitted with a brace of plaster casts, and from now on it was their duty to protect me; to prevent me from doing something that could injure me further. It felt horrible. At a stroke it was as if I’d lost my independence. No, in fact it was worse than that: I had lost my independence, because they would no longer let me do all the things I used to do, despite being just as physically able – actually, more so – as I’d been before I’d had to wear the boots. They were my badge of office: the signifier that I was officially disabled, and needed treating as a disabled person.

Not that I wallowed in feeling aggrieved by all this, any more than I wallowed in self-pity. I had my moments of frustration, but I tried to make the best of it; perhaps on a subconscious level I was trying to be defiant. They might think I was disabled, but I would show them!

And my refusal to be sidelined seemed to hit home eventually. By the end of that year I think my calipers were less visible; though teachers would still hover nervously around me, perhaps the absence of a regular need for Germolene had calmed them and they felt able to relax a little more.

In any event, I was deemed fit enough to take on my first acting role – in the school nativity play. It was a progressively comic one and I was pleased to land a role that would demonstrate my talents in this area. It wasn’t a big part – I had just the one line to rehearse – but it was one that was guaranteed to get laughs. Being good at headstands, I’d been hand-picked and my job was to deliver the line ‘What’s in this bucket?’ and then fall forward and do a headstand inside it.

There was to be only one performance, so there was no room for error, and I took my responsibility correspondingly seriously. And I came good, saying my line loud and proud before doing the headstand, to a delighted whoop from a clearly impressed audience. The only thing was that in rehearsals the bucket had been placed centre stage, whereas on the night it was placed at the back of the stage, up against the wall, home to the school’s highly polished set of wooden slats. Up I went – bash! – and down I came again, perturbed. Up I went again – bash, rattle! – and once again, down. Finally, the third time, I decided to stay put, my lower legs, as I tried to balance, drumming out a military tattoo, while the other children tried to perform their own lines over the din. When I finally came down – after however many noisy minutes with my shins rattling against them – the wooden slats that had long been the caretaker’s prized equipment were so scratched and battered by my calipers that they looked as though they’d been set about by a man with a serious grudge. By the time I left the school they still hadn’t had them replaced. Perhaps they are still there. I’d like to think so.

By the age of ten, fatigue had become an issue. I had always had a little trouble walking to and from infant school, and when I went to the juniors, though I walked around while there, my parents began to push me to school and back in an adult buggy. The thinking was that if I didn’t tire myself out on the journeys, I would be less tired both while in school and when I got home.

Though not as big a thing as the calipers, the buggy ride to school was still an issue, as it made me an obvious target for bullies. Most of the time I did my best to ignore them. I had no choice. If I went after the bullies in school, I’d only fall over, which would naturally encourage them even more. Luckily, I had a good friend – with whom I am still in touch today – called Andrew Russell, who helped me out of scrapes quite a few times. But there was one boy who was my nemesis. He was fast and he was mean and he was stronger than I was, and since I had spent so long falling over and knew exactly how much it hurt, I didn’t want to be pushed over by him. In fact, ‘didn’t want’ is perhaps understating my feelings about this boy: I could never get away from him quickly enough, and I would feel physically sick if I was in a situation where I knew it would be impossible to avoid him – not to mention his equally nasty sidekick.

Most of the name-calling I attracted was unimaginative and predictable – cripple-features, stick legs and so on. But one taunt was worse than others: spindle legs. ‘There goes spindle legs!’ they’d yell, whenever I came into view, and there was something about that one, particularly, that really upset me. I don’t know why, but the picture it evoked really hurt.

Looking back it seems the easiest thing in the world to shrug such a taunt off, but at the time, as any child who’s been bullied knows, it eats away at you, particularly if your self-esteem’s already fragile because of standing out in the way that I did. It’s a feeling I’m glad I remember in some ways, because it reminds me how far society has travelled in the interim. There will always be bullies, of course, and they will always find victims, but things are so much better, in that regard, for Ellie. Not only does she attend schools (specialist in the morning and mainstream in the afternoon) where she receives physio, support and all the help she needs to thrive, but there is also much wider acceptance of people with disabilities.

I was lucky, though, in that, like Ellie, I had brilliantly supportive siblings. Mark was in high school, of course, and Gary soon went to join him, but while he was still in primary school he always looked out for me. Though our paths didn’t generally cross during the school day, he’d always make sure he was there beside me at going-home time, to tell anyone who dared bully me to back off.

But my best support was Nicola, my little sister. She may have been small but she was feisty and was my number one protector. Mess with me and you messed with her – and she was a force to be reckoned with. Still is.

Which is not to say I was a pitiable figure in school – quite the contrary. Once I got to junior school, I increased in confidence daily. By then, I think I’d learned to play to my strengths, one of which was being in the right place at the right time, which suddenly stood me in good stead on the football field. I couldn’t easily run after the ball, so I would goal-hang instead, and if the ball came my way I would just kick it wildly, in the hope that it might hit the spot. And the first time it did, there was a sea change in how my peers viewed me. No longer was I Mr Last-pick when teams were chosen.

I was also treated differently by the teachers once I hit junior school: while they still stopped me from doing things I felt perfectly able to do, they didn’t seem to patronize me as much. Quite the contrary, in some cases, which was probably vital to my development; it wouldn’t have done me any favours to become someone who thought he could get away with not doing things he didn’t want to do, after all.

And I did my fair share of transgressing, like any other kid. A favourite transgression was not going straight inside after the bell had rung for the end of playtime, the punishment for which was having to stand on a black spot. I don’t know who thought up this particular punishment, but it was a sound one, in that it was so public. There were six black floor tiles, altogether measuring about 20 inches square, which formed a pattern underneath the main school staircase. If you were naughty, you would be made to go and stand on one of these – a kind of 20th-century equivalent, I guess, of committing an act of treason and having your head stuck on a pole, for all to see, on London Bridge.

But standing anywhere for long was an issue for me. Though the calipers corrected my foot drop, they did nothing to aid my balance, so remaining stationary was a challenge. So it was odds on, I reckoned, that when a passing teacher noticed my plight, I’d be excused an extended spell in position. But it wasn’t to be.

‘Here we are,’ she said, grabbing a chair from down the corridor. ‘Sit on that.’

It was probably a useful life lesson, that one.

Another was more gradual but equally enlightening: how the world views you when you’re long out of nappies but are still wheeled to school by your mother. Being in my adult buggy was an eye-opener from day one: a window on the world I would take my place in as an adult – a world that would see the wheels and treat me differently. I remember being pushed home by my mother one afternoon, and how the mother of a friend of mine stopped to speak to her. My father was unwell at that time, and had been home from work, so when the lady, looking concerned, asked Mum, ‘How is he today?’ we both naturally assumed she was talking about Dad.

‘Oh, he’s much better, thank you,’ Mum replied.

It was only then, as the woman looked solicitously at me, that we realized she actually meant me. I was old enough to speak, intelligent enough to speak and, to cap it all, her son’s school friend, yet because I was being wheeled home in a giant buggy, she assumed the correct approach was to talk about me rather than to me.

Looking back, I wish I’d mumbled and drooled all over her shoes.

But my time in mainstream school was fast coming to an end anyway. In 1974, when I was 12, it was decided I should be moved. Not to the local high school my brothers now attended, but to a state school called Martindale, in Hounslow, west London, which would be more suited to my needs.

Though a part of me really wanted to join my brothers at Harlington Secondary, in retrospect it would probably have been a nightmare. It had a lot of stairs, for one thing, and was quite a bus ride away, and having got there I don’t doubt I would have encountered as many bullies as I’d left behind in primary school.

I was also, at that time, beginning to experience a marked deterioration in my hands, which was starting to make it difficult to write. Mum and Dad had recently procured a manual typewriter for me, and I was beginning to learn how to complete my written work on that. Going to Harlington, therefore, would have meant not only bus rides and stairs and bullies but also the prospect of having to haul a heavy old-fashioned typewriter around to every classroom in the school – like some sort of roving correspondent. No, on balance, Martindale School it had to be. And, despite it being daunting to go somewhere so outside my experience, I remember actually being quite excited.

My last day in primary school was mid-term for some reason, and for all the challenges I’d faced in coming to terms with my disability, my overwhelming sense – then and to this day – was that the vast majority of people were – and are – friendly and supportive. The friendships I’d formed there would give me the confidence to face whatever was next. My friends also gave me a leaving present to remember them by: a Timex watch, which the whole class had clubbed together to buy for me. I was so overwhelmed that it was one of only a few times in my life when I couldn’t physically get any words out.

How I hope Ellie is similarly blessed.