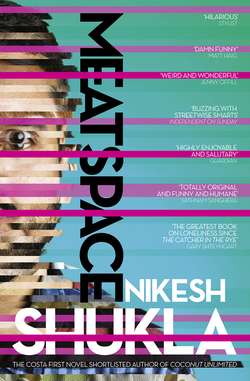

Читать книгу Meatspace - Nikesh Shukla, Nikesh Shukla - Страница 12

Tattoo disasters – Google Spying on people’s Facebooks – Google Best Asian author – Google Jhumpa Lahiri hot – Google

ОглавлениеIt’s Friday night (my dad’s usual slot for me – Friday for the children and friends, Saturday for the ladies) and I’m sitting in our favourite Indian restaurant waiting for him to arrive. When Dad shows up, he is dressed in a silk pink shirt, a leather jacket that goes past his waist, and black trousers. The only thing missing is some crocodile shoes. Instead my dad is wearing the omnipresent black Nike Air knock-offs he’s been wearing for the last 20 years, which keep his now-mangled feet breezy and comfortable. I once bought him some proper Nike Airs but they’re boxfresh, unused – ‘unused to my feet’, Dad said. His feet are now moulded to the shape of the inside of these cheap versions. He is holding on to the remnants of his sparse, thin, silky silver hair by growing around the bald crown a fine mane as long as possible.

‘What’s new, kiddo?’

‘Rachel wants to be my friend on the Facebook.’

‘She wants to be back together? Good, I like that.’

‘No, just friends on Facebook.’

‘Why would she do that? Unless she wants to be back together?’

I don’t reply. We both snap poppadoms.

Dad spoons onion onto his shard and I stare at the bubbles on mine, before dipping it in the raita and crunching down, grimacing at the sugary yoghurt.

‘Thank you for shaving. You know? Your face looks fat. Why is your face so fat? I need to work on this beer belly so I can get more dates, eh kiddo?’

When my mum died, when I was young, he went through a decade of wearing a fleece jumper and tracksuit bottoms, going to work in the same warehouse and coming home and eating the same food watching the same DVDs of the same Bollywood songs he and my mum listened to. It was a decade of mourning. Then he retired, and quickly realised how much of a social animal he is. He goes out 4 nights a week, wakes up in the early afternoons hung-over and watches old films till it’s time to go out again. He is basically me in my early 20s. Wednesday and Thursday nights, he props up the bar in his local Indian pub, watching cricket and counting masala peanuts (finely-chopped onions and chillies mixed in with dry roasted peanuts, drizzled in lemon juice and chilli powder) as dinner. Fridays and Saturdays are date-nights for him. He only ever has dinner with me or with a lady. And because he’s the type of guy who stands on old-fashioned ceremony, he will never let his child or a lady pay for dinner. We eat for free.

‘Son, I am happy to see you because you are my son, but going out with guys is no fun,’ he says to punctuate a silence.

‘What do you mean? You can talk to me about football, girls, whatever you want …’

‘I go out with people to have fun, not talk. I want to flirt, to dance, to eat with a knife and fork.’

‘You can do that with blokes. Why do you need to date girls?’

‘These are not dates. They are my friends. The girls are all my friends. Because I take them out, we eat good food, listen to the music, and dance. And they laugh at my jokes.’

‘Because you’re paying to take them out.’

‘Why must you make me feel like they are my prostitutes?’

‘Because you make it sound like you pay them to let you take them out.’

‘Well, kiddo … I’m old-fashioned.’

‘And it is the oldest profession,’ I say, spooning onions into my hand and throwing them into my mouth.

I feel, as I always do at these dinners, the unsettling pressure to be my dad’s best friend as well as his son. Dad used to have 2 close friends whom he did everything with. They watched every sport going, from cricket to the World’s Strongest Man, drank together, played cards, even worked together. Now those guys have retired and moved to Dubai, leaving my dad to date and take me out for dinner. And be a barfly.

He finds friends of friends, divorcees or widows who want to be taken out for dinner and a dance and he uses them for company. He pays to take them out and they give him company. He has rules for prospective partners. He’s trying to protect himself from history repeating. He doesn’t want to outlive another partner.

My dad doesn’t ever want me to come to see him in our family home, probably because he thinks the sight of all the kebab cartons and empty beer cans, dirty bathroom and unwashed dishes will probably send me into a panic. I think of the state of my flat … Rach’s chutneys filling the fridge are the only civilised things left about me.

Dad will dress up to visit in one of his 3 silk shirts and come and see me in my part of town because he thinks it’s buzzy (he describes it as a ‘carnival atmosphere’) and filled with beautiful women. He’s always disappointed to learn that the crowd is rarely, if ever, middle-aged single Indian women looking to be wined and dined, only thin boys and girls not bothered by our presence in the slightest. Still, he pays. And it’s near my house, so I’m happy.

Dad, when first looking for a new girlfriend, set himself some rules and parameters. He laminated them on a card to stick in his wallet as an aide memoire. They were: she must be younger than me; healthier than me; Gujarati Indian but, not too traditional or religious; able to dance; tell jokes; know how to cook (and he goes on to reel off a list of my mum’s signature dishes). I repeatedly told him in the last year that he’s not going to find a replacement for Mum, not least because his parameters are too defined. He thinks, why mess with perfection?

‘How is your book doing?’ he asks me, placing his hands together in prayer formation, to show me he’s listening.

‘Okay,’ I say, not looking up from the table, as if enthusiasm would indicate failure. ‘Sales are slow, but you know, at least it’s out.’

‘But what is your marketing strategy?’

‘I let the publisher deal with it.’

‘How can you trust them to market you? You need to determine your market and sell the book to them.’

‘Sure,’ I say, to shut him up.

‘You better be writing a bestseller. One with police detectives in the countryside. One with murders and car chases. Something you can buy in an airport and a supermarket.’ He pauses. ‘And don’t talk about the past this time. No one wants to hear about the past. Talk about now, kiddo.’

‘That’s not my thing, Dad.’

‘You should though. Don’t think you have another inheritance coming to you. I’m spending it all now on enjoying myself. So, write a bestseller.’

‘Okay, Dad.’

‘In fact, you better not be spending Mum’s inheritance. You better be earning, kiddo.’

‘Yes, Dad,’ I lie. ‘I’ve been doing great. Really great.’ He doesn’t need to know about my job interview. Not until I have news. News that ultimately proves he’s right.

When he first signed up to Facebook, as a way of keeping tabs on all the women he fancied in his life, he didn’t understand how to phrase sarcasm nor that if he left a comment on my status update, everyone could see it. He used to sign off with ‘lots of love, your dad’ thinking that each comment was like a letter or email. Then he decided to use my self-promotion on Facebook to remind me that ultimately I had to make money from writing.

Kitab: ‘Hey guys, if any of you are in the Luton area, I’m reading from my book tomorrow.’

Kitab’s dad: ‘Son, I hope they r paying yr travel because this is an expensive ticket. R U getting paid? I saw yr bk is £2.46 on Amazon. What % r u making frm this? Lots of love, your dad.’

When I put up a link to my novel on my status, my Facebook friends would ‘like’ it or maybe even say ‘congratulations’ and ‘can’t wait’. He’d troll me by saying, ‘Can I buy this in Tesco? Tesco is the only bookshop worth its salt.’ Then when my book came out, he said, ‘You should make something that can be adapted into a film. Maybe I will read it then.’

A couple of years ago, when the film version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo came out, he left me a comment on my wall saying, ‘I read this Girl with A Dragon Tattoo book in 3 days. I still have not read your book. What does that tell you, son?’

His Facebook comments get 70% more likes than mine ever do. People prefer him to me. When Dad first joined what he calls ‘the Face Book’, it was all he talked about: its politics, its new language, its potential for stalking, and it bothered me how much he wanted to converse with me about its intricacies. I hate talking about social networking in conversations.

‘Kitab-san,’ Dad says, playing with his new smartphone. ‘While you were in the toilet, I just liked this photo of a girl on Facebook. She’s in a bikini. I cannot unlike it. She looks too porky. I don’t want to give her wrong impression.’

‘Dad, do we have to talk about Facebook?’

‘Come on, Kitab-san. I joined the Face Book because it’s the only time I see you.’

‘Do we have to talk about Facebook though? My father is the one person I hope I’m free from that rubbish. You didn’t add me. So, I added her. Are you following me back? What’s on your mind? What are you thinking? LOL. ROFL. “Like”. These words mean nothing anymore.’

‘What is a ROFL? I have not come across this.’

‘Dad, don’t you worry our language is changing? That we’re as concerned with how to socialise with people digitally as much as physically? That language is dying? That everyone is using these bullshit words to mean new things they don’t?’

My dad looks at me, chewing.

‘It means rolling on the floor laughing.’

He swallows, nodding to himself. ‘This would have to be a very funny thing. To laugh out loud, we have all done this. But to be rolling on the floor. I am happy that at least it means you now speak the same language as your Indian cousins. You don’t have to pretend you know Gujarati anymore.’

I watch him funnel shard after shard of poppadom, slathered in chutney and onion, into his mouth, chew loudly and talk slowly at the same time. He keeps his nails long, and years of turmeric abuse have turned them yellow. He starts telling me an anecdote about his Friday night. The anecdote boils down to, I went to this bar and it was full of people half my age and the beer was expensive and I couldn’t hear anyone talk – but the way he tells it, I get the s-l-o-w version. I stop him mid-story so I can check my phone, which has chimed with a Facebook message. It’s from the other Kitab. Kitab 2. It says ‘Did you see my add request dude? What’s taking so long, same-name-buddies!’

Why is he messaging me, the weirdo? I stare at it trying to think of an appropriate response. I don’t know what to say. Can I just ignore it? Dad berates me for ignoring him.

‘What is on that phone all the time?’

‘Nothing – just messages from the world, telling me they love me.’

‘I got a new phone. A Samsung. You should try it. Better than this iPhone crap. Cheaper too.’

‘I’m fine.’

‘So, tell me about you, Kitab-san.’ Dad once worked for a Japanese company. He now calls me and all his male counterparts ‘name’-san. Unless he’s giving me advice, in which case, I’m ‘kiddo’.

‘Oh, you know … I have this book reading this week where I …’

‘You know, I found this restaurant to go to with one of my lady friends. It’s called Strada. Heard of it?’

‘It’s a pizza chain.’

‘Any good?’

‘It’s a chain. They’re all of an equal standard.’

‘No, this is Strada of Knightsbridge.’

‘Yeah, Dad, it’s a chain.’

‘Well, I’m going to take Roshi there for dinner.’

Our food arrives. I Instagram the curries in their steel dishes and upload the photo, adding the caption, ‘Dinner with my dad. He pays for the food. I pay for my lack of achievement. We both pay for the over-indulgence in the morning.’ Dad hesitates and then dives in. Hayley comments on the photo: ‘Delish x.’

I reply: ‘I’m with my dad. Rescue me.’

Dad is rarely keen to know what’s going on with me, and that’s fine because half of it he wouldn’t be interested in (emails about things that don’t emerge; short stories for magazines he’ll never read, that I never read; ideas for self-promotion) and the other half is not for his ears (my lack of earnings, my lack of social or sex life, my lack of consistent happy mental state). Whenever I used to talk to him about my sadness about my mum, he used to tell me I had no right to grieve as much as him because I’ve only lost a mother, whereas he’s lost a life partner. I argued that a life partner was replaceable while a mother wasn’t. He would say, ‘Wait till I introduce you to your new stepmother.’ Since the last time, we don’t talk about my mum anymore because I don’t want him to know about my grief and he doesn’t want me to think he’s a depressed alcoholic anymore. He drinks a lot. And not just quantity of booze, but quality too. I worried for years he was a functioning alcoholic. Able to go to work hung-over and not able to enjoy an evening till the first whisky and soda had been downed. Every night sat listening to his iPod of sad Bollywood songs, a bottle of vodka next to him. He told me once, ‘I try to drink enough so I don’t dream. Because my family is in my dreams all the time. I don’t want to see them. I don’t want to see what I’ve lost.’ He lived on vodka and whisky, and takeaway food. Along with the various medicines for his ailments, every morning, he’d take 2 ibuprofen for his hangover. My concern led me, in the darkest part of our grief, to take him to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and depressed by the stories from people indistinguishable from him, he laminated a card that said ‘Remember to no longer drown your sorrows in a bottle’ and stuck it on his liquor cabinet. Which was effective because it got him to go out more. Which pleased me no end because I had bought him the laminating machine as a Christmas present 7 years ago and he’d finally found a use for it.

I laughed to Aziz that what I’d done was effectively said: getting drunk every single night and crying is not good; going out and getting drunk every single night, on the other hand … well, that’s just the rest of the country, mate. Aziz’s attitude was, ‘Leeeeeave it, bruv. Let papa have fun. He worked 7 days a week for 50 years.’

‘This one girl,’ Dad says, laughing. ‘She is violent. I tell you. I said to her, if you want us to go out again, maybe lose some weight, eh?’

I can see chunks of naan in his teeth.

‘Dad, you can’t say that, it’s horrible. It’s sexist.’

‘It’s true. She asks to share a garlic naan with me then eats all of it? No way, kiddo. No more sharing for me.’ Dad shoves a large piece of garlic naan into his mouth to illustrate his point.

‘Maybe she was being romantic.’ Dad laughs with his mouth open.

‘Why did she punch me in the stomach for calling her a fatty then, Kitab-san?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Look her up on the Face Book. Her name is Pinky Marjail …’

I am part disgusted and part intrigued. What if my balding-fatter-older-version-of-me dad is North West London’s premier player, swimming in 60-something gash. What a guy.

‘Should I be on Tinder?’ Dad says, looking around. I don’t answer him.

I swig from my undrunk glass of red wine. Dad insists that a dinner isn’t complete without an accompanying glass of red wine – we never drink it, neither of us is partial. But damn, do we look classy eating.

I go home that night, feeling something nervy and burning in the pit of my stomach. I assume it’s a mixture of eating hot spicy food quickly and my nausea at my dad’s singledom. I’m glad he has someone he can talk to freely and easily. I wish it wasn’t me.

A bus goes past. My head turns when I think I see someone I know on the top deck. Except it’s just some Indian guy and I’m not sure where I recognise him from.

I walk into the flat. Music starts up and Aziz is on the kitchen table bellowing at me, using a banana as a microphone.

‘I’m giving you a loooooong look,

Everyday, everyday, everyday I write the book.’

I wake up the next day and check my emails – only notifications. I tweet: ‘2 nights ago we found my bro’s doppelganger online. I’m still creeped out.’

I get no interactions. I click onto a Tumblr. Someone I follow on Twitter is taking a photo of the nape of her neck for 365 days, documenting it from normal to love-bitten and so on. The photos, all fleshy white nondescript stretches of skin, are hypnotic and the day-by-day nature of the Tumblr gives me a forward-thrust in my own inertia. She gets a lot of love-bites.

I’m making breakfast and staring out of the window at the bathroom of the house at the bottom of our garden, hoping to glance someone, anyone in the shower, opaque pixels of pink flesh, and listlessly stirring porridge when Aziz comes bounding in. He fills the room with his energy and he moves around the kitchen in loaded silence. He smirks audibly. He hovers over me. He leans back against the counter. He reaches over me for things, breathing quickly.

I unenthusiastically ask him what’s up, knowing that whatever he tells me won’t wake me from my hangover – Aziz and I finished off my Budvars when I came back in last night, and then moved on to rum, and my head’s pounding. He and I have mutually exclusive moods this morning. But thankfully he has work to go to and I have an inheritance to burn through while pretending to work on my second, all-important novel. I’ll probably go back to bed with my laptop and a pre-downloaded cache of illegally acquired American sitcoms and dramas to keep me company till I fall asleep for my mid-morning thinking nap. Or look at videos of American college girl parties and feel sad about male pack mentality whilst tugging at myself.

‘How was Dad?’ he asks.

‘Fine,’ I reply. ‘Same. Exactly the same.’

‘He ask about me?’

‘He’s only interested in his own life,’ I say, and Aziz nods. He looks around the room for something to distract us. He sticks his finger up.

‘I wanted to tell you last night but you fucked off to bed. I’ve found him. His name’s Teddy Baker, like the suit makers and he lives in Brooklyn, and I need to get out of the flat more, man. I’ve babysat you enough. Time for Aziz to get back on the adventure train. So, guess what? I booked a trip out to go find him. I’m going to surprise him. I’m going to New York. The dream, Kit. The dream is happening. I’m going to bloody New York.’

‘What are you talking about, Aziz?’ I ask, my mouth full of cereal.

‘The bow tie tattoo man. I did some Googling when I got in last night. I found another copy of the same photo, but this time with his name as the file name and that led me to his Facebook page and his Twitter stream. Sorted. The guy sounds wicked. He likes dubstep, he LOVES The Wire. I like dubstep and The Wire. Peas in a pod, Kit. Peas in a motherfucking pod.’

‘Why are you going to visit him?’

‘I need to populate my blog with content. I did that one post and then nothing for months. I’m stagnant before I start. I just need something to write about. A proper adventure. And tracking my doppelganger down might be it. I mean, it’s better than what I was thinking of doing … I was considering doing a photoblog of my manscaping everyday for a year.’

‘Sounds like a dumb idea. He’s just some guy off the internet. He could be a weirdo. He’s probably a weirdo,’ I say, gripping my temples. My stomach churns at the thought of Aziz leaving.

‘This isn’t 2001, when only weirdos and perverts and Dungeons and Dragons were online. Everyone’s online now. Normal people. Secretaries and estate agents. And quantity surveyors. Who’s more normal than a quantity surveyor?’

‘And people want to read about that?’

‘Yeah, but it’s about the journey to find him, about tracking him down … that’s the entertainment.’

‘Google destroyed the journey, man. All you have to do is look him up on Facebook and boom, journey over. Message him – he either says, yeah man, stop by or fuck off weirdo and boom, end of journey … over,’ I say, not wanting him to go.

‘Kit, man … it’s just a laugh. I haven’t had a holiday in for ever. I’ve never been to New York. Mimi lives there now and I’ve got unfinished business in her pants. Why the why not?’ Aziz says, opening the drawer where the painkillers are. ‘New York’s the dream.’

‘I dunno. I’ll miss you. You never go away.’

‘Bruv, if I’m not around, you can’t use me as an excuse to not write. I’m going. It’s for both of our goods. I get to bang Mimi and have the most legendary time, and you get silence. No distractions.’

I cover my nose and mouth with my hands so Aziz can’t see I’m frowning.

‘When you going?’ I ask, wondering how I can talk Aziz out of it.

‘This week. After I’ve got my new tat. I’m getting the bow tie.’

I look at Aziz with a mixture of pity and confusion. ‘Why? Man, it’s not a good look.’

‘Buddy, it’s the one. It’s the one of ones. It’s the one most toppermost of the poppermost. I want it. I want to turn up at Teddy Baker’s yard with a matching tattoo pulling the same shit-eating grin and I want to film his reaction. Wanna be my camera man?’

‘I can’t, man. No money,’ I say, hoping my financial plight will cause him to stay. I can’t afford flights to New York. How else will I be able to afford beers and frozen pizzas?

‘Little Lord Fauntleroy starting to feel the pinch?’

‘Little Lord Fauntleroy needs to put his CV together today so he could find some B2B journalism soon just to keep steady income coming in.’

‘Sorry, man,’ Aziz says, rubbing me on the back. I stand up and walk to the open drawer with the painkillers. I take 2 out and dry-swallow them, hoping they’ll kick in with immediate effect.

‘It’s alright. I should have written something better.’

Aziz claps his hands to signal the moving on of the conversation.

‘Well, remember to finalise your tattoo designs. I booked you in.’

‘I don’t think I want a tattoo.’

‘I hate your hangovers, they’re always so full of regret. You’re so boring. This is why I need to get away. This funk. This funky stench. This funkington manor.’

I’m walking down our local high street staring at the gentrified ghetto of vintage shops, hipster bars and pound shops, marvelling at the busyness and bustle of 10 a.m. on an unseasonably chilly early autumn morning. Who are all these people and why aren’t they at work? Part of me realises that the innate nature of the hipster is not being in gainful employment but running about sorting out installations, video shoots and drinking coffee and talking about meta-collaborations. None of these have any place in a conventional office.

I tweet: ‘If the innate nature of the hipster is to avoid jobs, what do they do for money when there’s no installations to be done?’

@kitab: ‘They all suck each other off and roll around in piles of their parents money’

@kitab: ‘burn socks’

@kitab: ‘Develop Eating Disorders ;)’

I record constructions of a series of nothings in either chronological or flashback order. I string together a few similes like a hack and I send it to my agent and they will either ‘like’ it and ‘share’ it or unfollow me. Either way, I’m stuck in a rut of nothing. I don’t really appreciate what I do, why should anyone else? I used to read so much. I used to sit in cafés and read. I’d struggle to eat with a knife and fork or with my hands as I navigated sentences on a page. Now that’s all been replaced with thinking of arch things to tweet, twitpic’ing my lunch or making up overheard conversations that might make people laugh.

I tweet: ‘Im in a café & this girls like to her boyfriend “Jamie, I wish you hadn’t fucked me in the arse so hard. I cant stop shitting myself.” ZOMG.’

@kitab: ‘LOLZ’

I get 13 retweets and it didn’t even happen. It gets 4 favourites. Even Hayley tweets me to say: ‘We’re reading together this week! Haven’t seen you in ages, blud. See you at @welovebooksbitches!’

I think I see someone I know sitting in an internet café. I realise it’s just another Indian guy with an oily side-parting.

It’s inevitable I will get ‘Everyday I write the book’ tattooed on my forearm. Maybe drunk me knows me better than real me.