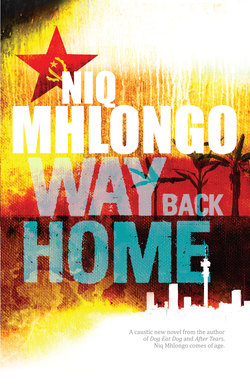

Читать книгу Way Back Home - Niq Mhlongo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Kimathi was a real son of exile. He was conceived in an act of unromantic lust in the village of Mazimbu Darajani, also known as Dark City, near Morogoro in Tanzania. His father, Lunga Tito, was a Xhosa man from Dimbaza, a township some twenty kilometres outside of King William’s Town. His mother, Akila, was a Swahili from Kwa-Ngiriki. Kimathi spoke both Xhosa and Swahili fluently. His parents had met in Kwa-Ngiriki in January 1969, when Lunga was in exile in Tanzania. Kimathi was born the same year, on 31 October, which meant he shared a birthday with his father’s struggle hero, Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi Waciuri.

Kimathi’s father died in 1985, after suffering from depression and being suspended as camp commissar at Morogoro. Reports claimed that Comrade Lunga had become frustrated and shot dead six of his colleagues in their sleep before turning the gun on himself. As a commissar he held a critical position in the camp when it came to the education of new recruits. The Movement had suspended him because of allegations that he had lured new female recruits into his bed by providing them with supplies he stole from the logistics section, including clothes, toothpaste, meat and alcohol. On the night before he killed himself, Comrade Lunga asked a young comrade, Ludwe Khakhaza, his most trusted student, to look after his son. He pleaded with Ludwe to take Kimathi to Dimbaza with him once the struggle was over.

After he killed himself, The Movement decided that Comrade Lunga’s actions were despicable and amounted to desertion; therefore he was not given the respect other struggle heroes were afforded. Kimathi’s mother died eight months later.

Ludwe fulfilled his promise to Lunga when he assisted Kimathi with his application for indemnity and a South African identity document in 1991. Obtaining the indemnity was important for exiled freedom fighters like Kimathi, as it was the only way to enter South Africa legally. Otherwise, he would have risked prosecution for crimes committed as a member of The Movement. He entered South Africa on 27 July 1991.

With the compensation that he received from The Movement, which was less than three thousand rand, Kimathi had rented a flat in Hillbrow. He knew little about Johannesburg and South Africa. Before he came to the country, he had imagined cities built on gold. At least, that was what his father had told him during one of their many walks on the banks of the Ngerengere River, near Morogoro. This particular walk had taken place after one of his playmates at Likobe Primary School had derogatorily called him “wakimbizi wa Africa kusini”, Swahili for “a refugee from South Africa”.

“I want you to fight for your country, South Africa,” his father had said to him when Kimathi had come home from school crying. “Tell those morons in Dark City that you’re not a wakimbizi, but a social reformer. Tell them you’re from a country where the cities are built on top of gold and diamonds. You are a revolutionary.”

It was on that day that Lunga decided that he needed to send his son to military school.

Kimathi began his life in The Movement as a student at Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College, or SOMAFCO for short. He became active in 1984, when a rumour circulated that the school might be targeted by the Boers. He was then tasked, together with other youths in exile, with digging trenches all over the campus. It was during this time that he met Comrade Ludwe properly for the first time – he was supervising the trench digging – and learnt of his connection with his father.