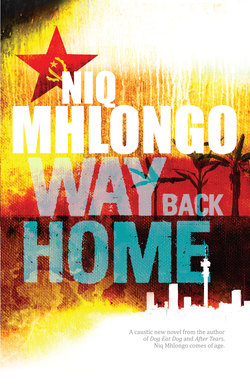

Читать книгу Way Back Home - Niq Mhlongo - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 5

It was Ludwe who reunited Kimathi with his family in Dimbaza in February 1992, six months after he had arrived from Angola. This was the happiest day in Kimathi’s life. His father had told him a lot about his aunt, Yoli, and seeing her for the first time was a great thing.

Kimathi had carried with him two old photos of his father, taken at SOMAFCO when he was still a commissar for The Movement. In both photos, Lunga wore two-tone Florsheim shoes, khaki bell-bottom trousers and a floral shirt that hung open to expose his hairy chest. He also sported a huge Afro.

Yoli was unable to conceal her joy. “Oh, God is alive. He left here in August 1968. In fact, he just disappeared.” His aunt smiled as she looked at the pictures. “He only wrote to us once, saying that he was in exile, but did not specify where.” She paused and expelled her breath through stiffened lips. “I assume he is no longer alive.”

Yoli looked at Kimathi for a reply, but instead it was Ludwe who spoke. They had agreed that he would do all the talking, especially in relation to Lunga’s death.

“He died in Tanzania from gunshot wounds in 1985,” Ludwe said with exaggerated grief. “He was my father figure in Tanzania. I left to go into exile in 1977, at the age of twenty. Comrade Lunga was already known as mgwenya, a veteran, when I arrived in Tanzania. He made sure I was well fed and clothed. He was my teacher.”

“Was he shot by the Boers?”

“Yes,” answered Ludwe, wiping an imaginary tear from his left eye. “He asked me to bring his son back before he died. He talked so much about you.”

“Is your mother still alive?” Yoli asked, addressing Kimathi directly.

“No, she passed away in 1986,” Kimathi answered.

Yoli spat on the ground to express her sympathy. “Shame, what was her name?”

“Akila.”

“Were they married?”

“No, they were never married,” Kimathi said, smiling sourly.

Yoli wiped her nose and then pinched it. Her eyes closed tightly, then opened and focused on Kimathi. “Don’t worry, this is your home. I’m your mother and your aunt now.”

“Thank you,” said Kimathi, licking his lips.

“When were you born?”

“October 1969.”

“How come you know Xhosa so well?”

“My father used to teach me, and there were lots of South Africans in Tanzania.”

“Do you have a Xhosa name?”

“I’m Fezile.”

Yoli hid her surprise with a satisfied smile. “That was your grandfather’s name,” she said, nodding energetically. “I’ll take you to your grandmother’s grave tomorrow.”

“Thank you,” said Kimathi. “And Grandfather, is he still alive?”

“Unfortunately we did not bury your grandfather. But tomorrow we will slaughter a goat, and I’ll introduce you to your stepbrother as well.”

Kimathi looked confused.

“Oh, didn’t my brother tell you that he had a son while still in high school?” Yoli asked. “When he left in 1968, in August, his high school girlfriend, Bulelwa, who was also my friend, was six months pregnant. The two families were planning to meet and negotiate the damages when my brother disappeared. Nakho was born in November of that year.”

“Where does he live?” Kimathi asked.

“He is in Dikeni.” Yoli paused. “That’s where his mother was originally from. In fact, my daughter Unathi stayed at their place when she was studying at Fort Hare. I’ll call him later.”

“I can’t wait to meet him.”

“He is a very sweet boy.” She paused. “We are originally from Middelburg. I was thirteen years old, going on fourteen, when we were forcibly removed to this place. Your father was two and half years older than me. We came here by truck in 1967. The Boers simply asked my father, Fezile, where he originally came from. The next thing, they gave us a day to pack our things. The following day they locked our house and told us to wait for the truck that would take us to our new home.”

“That was very cruel,” said Kimathi.

Yoli lapsed into silence for a while, her eyes filled with tears.

Ludwe palmed his shaven head, then sat back in his chair, flipping one leg over the other.

“I remember it was raining on that day. Your father was about to finish school; he was very brilliant in maths. The Boers didn’t even let him finish his final year of school, or write his exams, which were coming in three months’ time. He had wanted to go to Fort Hare to do medicine or law. My father was arrested because he had initially refused to move here to Dimbaza.” She stopped to wipe away a tear.

“Was Grandfather also a politician?” asked Kimathi.

“No.” Yoli shook her head. “He had big land where we planted maize, beans and potatoes. He also had many goats, pigs, and sheep. When he was taken to jail, we were brought here to Dimbaza, to this house, which was initially a wooden shack with a zinc roof. My father only joined us here six months later, but when he came, he decided to go and check his farm in Middelburg. There he found out that it was now owned by some Boer called Viljoen, who had also inherited our livestock. That’s when my father joined The Movement.”

She paused and then continued, “One day, during the night, he went back to Middelburg and killed Viljoen. After that incident, our family was constantly harassed by the Boers, and that’s when your father left for exile. My father was caught in 1972 and hanged. We were never given his body to bury.”

They shared a second of eye contact and Kimathi saw a spasm of hatred pass across Yoli’s face – she was obviously not the forgiving type.

“This house was improved by my mother, Nomakhaya,” Yoli continued. “When we came here in 1967, it was just a leaking structure, but as you see now, it is a beautiful four-bedroom house. She used to work in King William’s Town, making dresses in a factory until she passed away of cancer three years ago.”

“That’s not long ago,” said Kimathi.

“Amabhunu ayizinja, mntanami. They are dogs,” Yoli concluded. “When we were forcibly removed, our six-year-old brother passed away in the back of the truck because of the cold. Now they want to reconcile? Reconciliation se voet! I’m glad my brother Lunga taught you politics. You and me must go back to Middelburg and claim our ancestral land from the Viljoens. Our great-grandparents’ graves are there. Now we cannot go and perform our traditional rituals because of those white bastards.”

Yoli paused for breath, and then continued, “I went to the council to reclaim that land and they say I must come with title deeds. Where do they think I’ll get that paper, huh, mntanami? When I told them that our farm stretched from the two tall fig trees to the stream, they didn’t believe me because those trees are gone now. The Boers have chopped them down to hide the evidence. Those trees separated our farm from the Bacelas, who were also evicted.”

She stopped and looked at her fingernails as if to examine the dirt beneath them. “Those council people looked at me as if I was a mad woman when I told them that those trees were our title deeds before the Viljoens occupied our farm. I’m no longer voting for any political party because they are failing to solve our problem of land.”

At that point, a lady with an oval face entered the house. She was wearing a beige floral-print dress, a multi-strand necklace and brown showstopper heels. Ludwe’s eyes settled on her for a very long moment. Her face was flawless.

“This is my daughter Unathi,” said Aunt Yoli.

That night, before they slept, Ludwe spent some time talking to Unathi. She was interested in knowing more about her Uncle Lunga, and he seemed to be the right man to talk to. They exchanged contacts and Ludwe promised to use his network to try and get her a job in Joburg.

The following day, the family prepared a great feast for Kimathi and Ludwe. A goat was slaughtered to welcome Kimathi home. After the party, they went with Nakho, Kimathi’s stepbrother, to the cemetery where their grandmother was buried. Nakho looked exactly like their father. However, despite everything, Kimathi felt no connection with his father’s home. Unathi and Ludwe, however, continued to talk, and on that day he was even able to put his arms around her. She agreed to visit Kimathi in Johannesburg, and she and Ludwe were married a year later.