Читать книгу In the Land of Israel: My Family 1809-1949 - Nitza Rosovsky - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

MORDECHAI MOTTEL ASHKENAZI

ОглавлениеBaba Esther often talked about her father Mordechai Mottel who, after marrying Haya Epstein moved to Tiberias, where he joined the Russian kolel to which his father-in-law belonged. Years later he applied for British protection, a move made possible by the Capitulations which placed non-Ottoman citizens—as well as people under the shield of a foreign power—within the legal safeguards of their own consular representatives. Great Britain in particular became a patron of the Jews in Palestine and came to their aid on numerous occasions. Being under British protection had many advantages, which explains Mordechai’s application addressed to the British consul in Haifa and dated April 1, 1872. I do not know whether British protection was granted to the family.

In 1865, many people died in Tiberias during a cholera epidemic. The city had no real medical facilities and the need for a hospital was acute.15 In 1872, three kolelim, Volhyn, Karlin, and the Russian kolel—the latter represented by Mordechai—joined together in what was known as Hevrat Bikkur Holim, “Society for Visiting the Sick.” A courtyard and four houses which belonged to the kolelim were made available to the society and soon some sort of a hospital was set up there with a doctor who appeared at irregular intervals. But the city’s hot climate and poor sanitary conditions brought on many diseases which the small facility could not handle. So in 1883, several rabbis and officials from Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias, and Hebron came out in favor of building a proper hospital in Tiberias since the city’s therapeutic hot springs attracted a large number of sick people. Two years later, in the spring of 1885, Israel Dov Frumkin, the editor of Habazeleth, visited the city and wrote at great length about the need for a hospital. (His paper, an organ of the Hasidim, was one of the earliest Hebrew newspapers in the country, first published in 1863.) That summer a group of seven people wrote to Frumkin, hoping he would publish their letter in Habazeleth and get others to support building a hospital. In Tiberias, they noted, even those who came to the hot springs had no one who could tell them how long they should stay in the water, and since “there is no doctor, there are no drugs ... [and] people die before their time.” Mordechai Mottel Ashkenazi was the first person to sign the letter. I came upon it unexpectedly, in 1989, while searching through the Zionist Archives in Jerusalem (File: Tiberias, A199 #59). I had just returned from Tiberias, after one of my futile searches for Mordechai’s tomb, so finding a letter with his name on it was simply overwhelming.

The need to set up a Jewish hospital became even more urgent when a Scottish missionary group—the Committee for the Conversion of the Jews—decided to establish the Sea of Galilee Medical Mission in Tiberias. It opened a clinic there in 1885, headed by Dr. David Watt Torrance, and inaugurated the Scottish Hospital ten years later. Providing health care was a tactic often used by missionaries in the Holy Land. While most Jews shunned efforts to convert them, many were tempted to consult a doctor—even an evangelizer—if the life of a child was in danger and no Jewish doctor was available. Once a Christian health facility opened, the Jewish community galvanized to offer similar care, and so a Jewish hospital was finally built in Tiberias in 1896. Dr. Torrance, it turned out, spent little time on saving souls and devoted the next forty years of his life caring for the sick in Tiberias. He had a huge following among Jews and Muslims alike and was mourned by all when he died in 1923.16

I found Mordechai’s footprints in another episode. In 1891, before the Jewish hospital opened, a Dr. Hillel Yaffe was invited to Tiberias to see if he might be interested in serving there. In his memoirs Yaffe described his first meeting with some forty men, all Orthodox, dressed in white trousers and cotton or silk coats, with long beards and ear locks. A secular Jew, the doctor hastened to assure the gathering that he would not break any religious laws in his clinic nor would he force any patient to do so unless illness dictated it. One of the more important people in the group, wrote Yaffe, a man called Mottel Ashkenazi, stood up and said: “Sir, we already have a wise and God-fearing rabbi in Tiberias. What we need now is a medical specialist.” Pleased by this attitude, Yaffe accepted the position. Later, no one asked why he did not attend synagogue services: “They never worried about the relationship between God and me,” wrote the doctor in his memoirs. Eventually, a deep affection developed between the physician and the community.17 Dr Yaffe later became famous for his efforts to establish health services throughout the country.

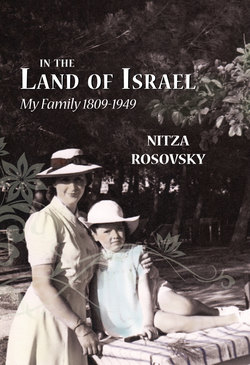

Little Jewish Boy in the Scots Mission Hospital, 1934-1939

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

I do not know much about Haya, Mordechai’s wife. Esther, her daughter—and my great-grandmother—claimed she spoiled her children and later her many grandchildren. She was an excellent housekeeper and learned how to cook local dishes from her Sephardi and Arab neighbors. (Esther was always quoting proverbs in Arabic that her mother had taught her. Concerned with good manners, she often repeated: Duq al-bab qabil ma tudkel. “Knock on the door before entering.”) Many of Haya’s female descendants were named after her, including my mother’s beloved sister.

Mordechai was quite liberal when it came to the education of Esther, the oldest child in his family that eventually consisted of four sons and three daughters. While most boys began to study in heder—a religious elementary school—at age five, girls were taught at home, if at all. (According to one tradition, Jewish girls learned enough Hebrew to be able to follow the prayer book, and enough of the local vernacular to be able to address an envelope.) Esther had an inquisitive mind and fortunately, she told me, her father was sympathetic. Either because of the bad reputation of the local heders or, as I like to think, for Esther’s benefit, he hired a tutor, a melamed, to come and teach his sons at home. Esther was allowed to sit in the same room and listen, so, indirectly she studied the Bible, Mishna, and Talmud. Due perhaps to poverty, the state of learning in the Jewish community in Tiberias was grim, especially among the Hasidim. Dr. Ludwig August Frankl, secretary of the Jewish community in Vienna who set up the Laeml School for Girls in Jerusalem, wrote after he visited Tiberias in 1856: “The city where the Sanhedrin, the Supreme Council, met and the great sages lived and taught, is now the seat of ignorance.”18

Esther did not shave her hair when she got married, as was the custom among Orthodox families and I give her father some credit for that. But against the practical, progressive image of Mordechai stand the instructions he left his sons, written on the back pages of one of the Humashim: “My dear sons, be careful not to bathe in the sea or in a river on the Sabbath. My dear sons, be careful not to take walks on the Sabbath outside a city wall or in a city without walls. My dear sons, be careful to pray in public because it is a mitzva often overlooked these days. My dear sons, be careful not to teach your children and your children’s children foreign [studies?] and especially European languages, and do not let them study in [secular?] schools.” Did he grow more conservative with age?

My great-grandmother Esther married David Brandeis, an ilui, a prodigy, according to family lore. Joseph, their oldest child, was born in 1878. Five years later, shortly after their second child, Sarah, was born something happened to David. One source says he drowned in the Sea of Galilee; another version has it that he studied too much and became mixed up, unbalanced. Whatever happened, Esther was left to bring up two children on her own. There was little a young woman could do to support herself in Tiberias during the 1880s, so others in her position returned to their parental home or lived with their in-laws. Esther, however, a forerunner of the liberated woman, refused to be a dependent. She tried to make a living by knitting sweaters and other garments, but there was little demand for her wares in the balmy winters of Tiberias and she found it difficult to provide for her two children. Meanwhile, Leah, one of her sisters, had married Moshe Elstein, a wealthy merchant who was living in Beirut. They could not have children and offered to raise Sarah, my mother’s mother.