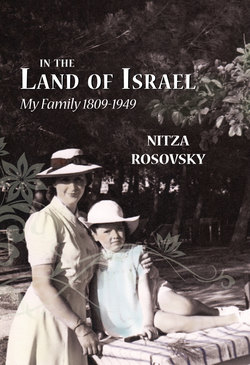

Читать книгу In the Land of Israel: My Family 1809-1949 - Nitza Rosovsky - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FROM BEIRUT TO JERUSALEM SARAH BRANDEIS-ELSTEIN

ОглавлениеWhen Sarah Brandeis-Elstein arrived in Jerusalem in 1906, she was wearing a wide-brimmed hat with black feathers, as was the fashion in Beirut. Numerous bracelets adorned her arms and a small gold watch dangled from a chain around her neck. Attractive and urbane, her reputation slightly tarnished by divorce, she married my grandfather, Eliyahu Halevi Berman, a twice-widowed merchant with two sons almost as old as his new bride.

When Sarah first went to market, children ran after her and shouted: “Look at her! Look at that hat!” She soon gave up the latest creations of Beirut’s milliners and settled for a plain kerchief, as was the local custom. Half a century later, after my grandfather died, she sold the house on Hayei Adam Street that he had built in the 1880s and moved to a nearby apartment. Helping to pack in anticipation of the move, I was sorting through piles of belongings when I came upon an old shoe box where, side-by-side, lay the baby locks of my uncle Moshe, Sarah’s firstborn, and long black feathers from one of her old hats.

General View of Beirut, 1898-1914

American Colony Collection, courtesy of the Library of Congress

One of my earliest memories is of my grandparents sitting together every evening after supper at the dining room table. He would be peeling an orange and offering it to her. (A diabetic, he was constantly urging the rest of us to eat what for him were forbidden fruit.) When she finished the orange he would take her hand and ask: “Did it taste good, my Sarahleh?” To me they seemed an idyllic, if ancient, couple. But back to the beginning ...

Sarah was four or five when she found herself in Beirut. Forlorn at first in the large metropolis, amidst the unaccustomed opulence of the Elsteins’ house, she sorely missed her mother and brother. But her adoptive parents doted on her; it was said in the family that “she lived wrapped in cotton wool,” sheltered and protected. Eventually the Elsteins won her over. She took their last name, and later, when her first son was born, she named him Moshe, for her uncle, and brought him to Beirut to visit. She named my mother, her second child, Leah. Since it is not customary among Ashkenazi Jews to name children after living relatives, an exception was made in this case, probably because the Elsteins were childless.

Moshe Elstein, Sarah’s uncle who brought her up, with Sarah’s son, Moshe, on a visit to Beirut, 1908

Moshe Elstein was an Orthodox Jew, but he was also a worldly man who traveled a lot, buying silk in Aleppo—on the ancient route of caravans from the East—and selling it in the West. He thought that Sarah should have an education beyond the prayer book and since there were no Jewish schools for girls in nineteenth-century Beirut, he sent her to a Catholic day school, run by French nuns. She did not eat there nor did she attend classes on Saturday, and she was exempt from religious instruction and church services. At home Sarah got to know many interesting people because her uncle was an early supporter of Zionism and meetings and discussions with like-minded individuals took place regularly in the Elsteins’ drawing room.

Sarah remained a pious woman, yet glimmers of her time among the Catholics lingered well into my own childhood. Take Christmas, for example, an ordinary work day for Jews in the Holy Land, although some marked it by playing cards or dominoes—frivolous activities normally frowned upon—to show their low opinion of the man whose name would not cross their lips except as “he who had lost his way.” Grandmother, on the other hand, would drag out one of her old school books and recite some version of the life of Jesus. By the time she reached the end she was always weeping, but since the book was in French, which I did not understand, it took me a long time to realize what the story was all about. It was especially confusing because sometimes she read aloud from another book dealing with the voyage of Christopher Columbus and the trials he faced just before reaching the New World. This she read in German and since I knew Yiddish I understood most of that saga. When the going got tough—for Christopher that is—Grandmother would shed tears once again, and for years, until I was seven or eight, I mistook Christopher for Christ, thinking they were one and the same.

When Sarah turned eighteen, a matchmaker was commissioned by the Elsteins to look for an appropriate bridegroom. I do not know much about her brief first marriage, not even her husband’s last name, only that he was nicknamed Velveleh, or Wolf. Sarah moved to Haifa, to his parents’ home, and in the beginning she was very happy. “He was young and handsome and we loved each other very much,” she told me. “We were always laughing, and all we wanted to do was to be near each other.” But Velveleh was the youngest son, the apple of his mother’s eye, and it seems that it was too much for her to share him with another woman at such close quarters. And so, the family story goes, she began to spread rumors about Sarah’s past, about her unorthodox education and her friendships with some of the young Zionists who frequented the Elsteins’ house. When the gossip reached Beirut, it infuriated her uncle Moshe and he sent her a telegram: “Sarah, come home.” He then dispatched Eliyahu Klinger, another uncle of Sarah’s, to Haifa and together uncle and niece left for Beirut. According to Sarah she and Velveleh cried bitterly at their parting.

“How could you do it?” I asked her. “You loved him so. Why did you leave?”

“Mein kind—my child. You don’t understand. Perhaps, if it had been my real father who had ordered me home, I might have disobeyed him. But I owed so much to der Fetter Elstein, to Uncle Elstein, who was so kind to me. It would have been unthinkable not to do as I was told.”

Many years later I heard from my aunt Zahava who grew up in Haifa that Sarah’s divorce was a cause célèbre in the city, where the former mother-in-law was considered to be a wicked woman. It was said that she was cursed because of her behavior; another one of her sons died young and destitute and left behind five small children whom she had to raise. Sarah never went back to Haifa. She stayed in Beirut, a young divorcée in a precarious social position. Before her marriage she mixed freely with the students who visited her uncle’s house and was an active participant in events organized to raise money for various good causes. But now on such occasions she just sat at the door and sold tickets or else stayed home and perfected her embroidery. At times, she told me, she felt so trapped that she would rise at dawn and escape to a deserted beach nearby, where she would shed her outer garments behind a large rock, as she used to do when she was a child. Her aunt did not think that swimming was a suitable pastime for a young Jewish girl—and certainly not for a divorced woman—so Sarah did not own a bathing costume. She would make sure no one was on the beach and in her bloomers dive into the balmy waters of the Bay of Beirut.

Cabinet portrait of my grandmother, Sarah Brandeis-Elstein, which she sent to Eliyahu Berman, 1905

Photograph by A. Noun, Beirut

Meanwhile, her family was busily looking for another husband for Sarah. Her uncle Eliyahu Klinger—who had married Hinke, Esther’s youngest sister—was a prosperous merchant and banker who often traveled on business from Safed to Jerusalem where he heard of a possible candidate, a most reliable man, a widower. Soon photographs were exchanged between the parties. I still have Sarah’s picture, taken by “N. Aoun, Photographe, Beyrouth, Syrie.” Perhaps a bit plumper than is fashionable today, she looked quite appealing in a white dress with many strings of seed pearls around her neck. Her dark hair was piled high, a few tresses falling across her forehead. The photograph must have pleased Eliyahu Berman who came to Beirut to meet her, then married her and brought her to his house in Jerusalem.

With Sarah’s departure for Jerusalem, my story shifts away from the Galilee, from the Ashkenazis and Epsteins. The history of the Bermans was easier to trace since I grew up among them, listening to stories about their early years in Jerusalem, familiar with most of the characters.

Entrance to Jerusalem through Jaffa Gate

Photograph by Bonfils, 1880s

Courtesy of the Berman Bakery