Читать книгу The Girl Who Stole My Holocaust - Noam Chayut - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

This book was born of an accident. Let me explain. I traveled to India for my vacation. One of those post-graduation trips. That is the Israeli code name. A good definition for what you do in life helps you place yourself in society. As I sat in a dhaba—a cheap Indian restaurant—in the town of Rishikesh, an Israeli girl approached me and posed a question.

“Student?” she asked.

“Yes,” I answered. “Actually, I’ve just graduated.”

“Oh,” she said. “Then you’re on a post-graduation trip. Me and my girlfriend are on the last leg of our post-army trip. It’ll soon be a year. How long can we keep going? We’ve had enough. We’re heading home, that’s it. How long are you planning to travel? Wow, cool.”

And that’s how I came upon the definition for this period of my life. From Rishikesh I headed north to Leh, in the Ladakh desert. First of all because I like deserts, and second because of the monsoon season in the south. This is also the ideal time to explore the Ladakhian plain, which is frozen over the rest of the year.

Leh is a charming town in the heart of a breathtaking landscape: a green oasis surrounded by an expansive desert. The ground is colorful, with bright yellow, brown, green and red stretching out all the way to the horizon, in fascinating contrast with the distant snowy peaks ornamenting the barren plain.

Leh is beautiful indeed, but it did not welcome me.

At first I suffered altitude sickness—I simply had no air. Three or four days later, as I began to recuperate, some nasty virus attacked my partner and kept her in bed for a whole week, during which time I came down with violent food poisoning that kept me in the guesthouse and on the toilet bowl, tormented with nausea and horrendous belly aches. When we began to recover, we wanted to liven up our convalescence, so we traveled to one of the neighboring villages. There—perhaps because of the bedbugs or for some other reason—my partner developed a rash on her hands and neck that soon spread to her whole body. Still pale from her sick days, she resembled a white sheet with red spots all over it. Another two or three days went by and I, too, developed a rash on my hands, belly and forehead, while my nausea and dizzy spells continued.

When we finally felt better, we decided to try an experience favored by many travelers in that region: descending a mountain road on a bicycle. A Jeep took us up 5,200 meters above sea level, the highest point in the world accessible by road. From there we coasted back down on our bicycles to Leh, about fifty kilometers as the crow flies, and an altitude difference of about 1,700 meters. In the sheer adrenalin rush I lost all sense of responsibility or fear. I left the group far behind and glided among the mountaintops.

I felt the tremendous smile spreading over my face, hurting my cheeks, a smile reserved for skiing or galloping on horseback along the beach. I took one of the curves too fast. There was sand in the middle of the road and my tires skidded. I almost managed to stabilize myself on one side of the road but hit a protruding metal rod. My bicycle toppled over. I was hurled forward and crashed on some rocks. After rolling over once or twice, I found myself sitting on my ass, stunned and barely breathing. I cursed myself for my irresponsible speed, but was also proud of my “parachute landing,” which prevented worse injury. Except for some cuts on my knees, left hip and one hand, I found no other injuries. Thinking that the shock of falling had helped sustain my breathing, I returned to the bicycle and continued my ride, even enjoying it, although my breathing difficulties were replaced by a growing pain in my chest. Then it even hurt to sit down and stand up, to bend over and swallow, and especially to cough and yawn. Even the slightest sneeze resulted in pain lasting for minutes. I could only fall asleep on my back or curled up on my right side, but changing positions was torture and the pain woke me up.

A visit to the Ladakh hospital is a depressing experience, but at least my visit was cheap.

I was very glad to have included high-risk sports in my insurance policy. However, since registering for a doctor’s appointment cost only two rupees (or twenty agorot—Israeli cents) and the x-ray cost another forty-five, and the medication which I didn’t use cost another thirty rupees, all my medical expenses amounted to only seven Israeli shekels and seventy agorot. Even including the taxi fare to and from the hospital, the insurance charges cost less than the stamp for mailing the forms home.

In the x-ray room at the hospital was a woman sprawled in a wheelchair, her whole body badly injured. She had apparently been in a traffic accident. Her face was swollen, eyes shut, and her whole body was badly bruised. Outside, there was some commotion and the entire staff was glued to the window looking out. When I entered, I saw that the woman’s IV bag, connected to a vein in her right hand, was on the floor. It must have fallen, I thought. I tapped the shoulder of a white-robed woman and pointed to the IV bag and the connecting hub that was dripping blood. She shooed me away angrily and resumed looking out the window and chatting with her colleagues. I picked up the drip myself and went over to the next bed, tapping the shoulder of another white-robed woman to show her the dripping blood. She too ignored me. Then, when the injured woman was laid on the x-ray table, none of the many patients and staff in the room were required to leave. I was the only one who hurried out before the x-ray was taken. Apparently, the technicians do not understand what repeated radiation doses do to them or their patients. Or perhaps they understand very well and simply shrug, fully prepared to cross over to the next incarnation that awaits their Buddhist souls.

I waited in the corridor, facing the blue European Union flag, with its bright stars a proud reminder of the EU’s complacence and generous donations. Even when my turn came to be x-rayed and I was placed with my back to the wall, and the x-ray technician was already approaching the button, no one left the crowded room. I moved aside to prevent the x-ray, gesturing that I needed something to protect my precious testicles. The technician did not understand me so I left the room to look for something myself. In a corner of a side room—some kind of junk-storage space—was a pile of robes that seemed to serve this purpose. I wrapped them around my loins and was so proud of my resourcefulness that I never wondered about the light weight of the robe. When I got out of the room after being x-rayed, I realized I had merely wrapped myself with a synthetic cloth, empty of the lead shield it was supposed to contain.

I discovered that the only way to heal a fractured rib was to rest, and to do nothing else. I considered going back home to Israel and resting at my parents’ house, but I concluded that convalescing in India would be almost as enjoyable as hiking there, which had been my original plan. I also discovered that the most relaxed trip I could manage following my injury was amazingly similar to the trips taken by many other backpackers. I began to like the idea of recovering from my injury in India. One Belgian hiker recommended a place in northern India she said would be ideal for my purposes: “Go to Pushkar,” she told me.

A painful flight to the capital, a comfortable train ride in luxury class—and there I was. Pushkar is a village in Rajasthan, the largest Indian state by area, located in the northwest of the country. Pushkar is on nearly every Israeli backpacker’s itinerary. The food is tasty, accommodations are comfortable, and both are remarkably cheap. The village itself is quaint and picturesque. But the truth is I am not good at resting. After two days of reading and visits to Hindu temples and short slow walks around the lake, I was getting bored with resting.

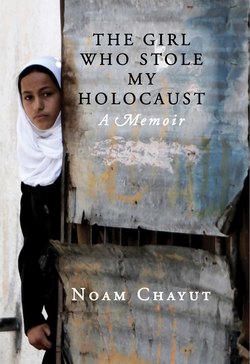

On the third day, while taking a hot morning shower, I had an epiphany. This will surely sound a bit florid but I know no other way of describing it: she came to me in a flash—the girl who stole my Holocaust. I saw her face clearly in my mind, that girl from my past. But it was not just a recollection; I also finally deciphered her real meaning in my life. So what might have otherwise been a traumatic memory actually filled me with bliss, for I knew I had an idea: a project was conceived. Sparing my fractured ribs, I held back a burst of joyful laughter and got out of the shower infused with energy and fresh power.

I dressed right away, picked up a notebook and pen and walked over to the nearest dhaba. I ordered a banana lassi—banana yoghurt full of surprises, like coconut, raisins and cashews—and began to write and write and write.

Writing, I discovered, made me happy the way I had been in my youth when I took theater workshops or performed music in public. Many of the reminiscences I committed to paper were harsh, but writing them down produced a sweet sense of relief. Although I had recounted these tales many times before, committing them to paper in my fresh, focused frame of mind was immensely pleasing and generated profound, unexpected insights. And so my imposed rest yielded these notes. They quickly became the true purpose of my trip to India. Every four or five days I would move to another beautiful place and walk around a bit or rent a scooter to briefly acquaint myself with the area. But every day at dawn and again at dusk I would sit down and enjoy throwing myself into writing.

Before my epiphany, I was often asked about the moment that transformed me, when I realized that something in me was wrong—the moment when my mind quaked. I used to answer that there was no such moment, no instant of enlightenment. It is a gradual emotional process, I would say, deep and long and full of fragmented realization. But that morning, on a beach ornamented with coconut trees, I had a new answer—this book is the answer to just that question. There was indeed such a moment, but it only became clear to me years after it happened.

October 2007, Varkala Beach, Kerala, India