Читать книгу The Girl Who Stole My Holocaust - Noam Chayut - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPART ONE

CHAPTER 1

I mustn’t be this sad. It’s just a Holocaust. My Holocaust. After all, there are many other things worth living for, such as love and the simple pleasure of existence. Not everyone has a Holocaust. Or even had one at some point. Here, these two Indian women sitting across from me in the restaurant with their huge platter of fruit, yoghurt and honey drops, they never had a Holocaust. And I got mine by birthright, never had to do a thing to earn it. So it would not be fair for me to mourn its loss. And still it hurts, losing my Holocaust. It hurts so very much. Glory snatched from me after a mere twenty-three years of life. How could I not be sorry? Some of my best friends and acquaintances still hold on to theirs. Why have I, of all people, been left without a Holocaust of my own?

Clearly I must introduce my Holocaust to you so that you can understand the splendor of which I was robbed. I must also share with you the story of its theft, for otherwise you won’t know how a Holocaust is stolen, will you? And while doing this I will also tell you about the thief herself. My encounter with the girl who stole my Holocaust is not at all a simple chain of events. For you to understand it, I will have to tell you how I happened to be led into that small village behind the lines—borders, but especially dividing lines of culture, logic and sanity—the village where this natural possession of my Holocaust was so forcefully taken away from me.

CHAPTER 2

I wonder whether any man, inspired by the sweet sadness of a Holocaust memorial ceremony, has ever proposed to a woman. I did. I proposed friendship. I swear! “Want to be my girlfriend?” I asked a pretty girl, the prettiest in our group, at the end of the Holocaust Memorial ceremony at our moshav.* I had an erection, my first as far as I can remember; it was perhaps the first thrill I experienced relating to the opposite sex. I was in the fourth grade and cried at the ceremony. I cried with pride, as I did at all the Holocaust Memorials of my childhood. I sat next to her and she cried, too, her cheeks chubby, red and wet with enticing tears. That’s Holocaust Memorial Day: everyone gets serious, wears a deep and concentrated look and cries together, mourning the “splendor of youth and glory of courage. Do not forget, do not forgive.”†

On the eve of Holocaust Memorial Day we would walk together, my father, mother, brother and sisters, to the community hall in the middle of our village. It was a huge building. One can hardly imagine how awesome and powerful it looked, especially to a young child. This feeling of awe prevailed not only during Holocaust commemorations, but also during “moshav festivities,” marking the founding of the village. The moshav celebration was originally held during the Hanukka holidays, but eventually the date was changed to coincide with Shavuot.* Over the years the celebration also moved outside the building, to the nearby football field.

In the winter of 1921—December 16 to be exact—the soon-to-be founders of the village where I was born loaded their wagons, harnessed them to mules and headed east towards Harod Stream. From there they crossed the gentle slopes above Tabun Spring. The animals strained at their harnesses, struggling with the muddy loam of the Jezre’el Valley, lands that had been freshly purchased and not yet drenched in blood. Toward evening, the pioneers climbed the hill where the village is now located and pitched their first tents just before the Hanukka holidays.

But the date itself was not sanctified and the moshav festivities were eventually combined with the celebration of Shavuot. This was done because Shavuot draws the energies of farmers past and present and of the community at large to hail the changing seasons, the bounty of the earth, and—perhaps not quite consciously—the granting of the Torah, whether or not the last of these actually took place. Doubtless its power has preserved this special date through two thousand years of exile.

The community hall was also where we celebrated simpler holidays. The youth movement used it to celebrate Hanukka, Purim and Tu Bishvat. The hall had a loft called “The Members’ Club” that was shrouded in mystery. Nowadays, with our culture so Americanized, we Israelis are somewhat amused to recall that the word chaver* had socialist or even communist undertones—“member of the moshav association.” As a child, I took it quite literally. However, the shouts that emanated from that club, the curses and profanities voiced by people coming out and passing by “The Stone,” did not resemble any kind of camaraderie I knew. These shouts came from the moshav members, all of whom would periodically gather in the club. This was called the “moshav assembly” and it had supreme authority, even more than the central committee.

By the entrance to the community hall was a large basalt rock that everyone called “The Stone.” This was our hangout, just as in other places youngsters used to sit on metal sidewalk railings or around the neighborhood playground. It was there I had my first smoke and used my first swearword. On The Stone I eyed with envy older kids who had motor scooters and mini-tractors; after a wild ride they would stop there with a screech of the brakes to parade for the gaping admirers. On The Stone I sat with my best friends, who over the following two decades would distance themselves from me and from each other, each off on his own orbit, and nothing would ever repair those friendships. But on The Stone we chatted and laughed and got bored together and looked for thrills. Some would break into the grocery shop and steal things, while others would sneak into the swimming pool on summer nights. Sometimes we would go out on “skirmishes” at the Home, a boarding school for needy children in the center of the village. We called them “the homers” and they called us “the villagers.” In the battles held at recess in our joint school, the homers usually had the upper hand, because our gangs were no match for their sixth graders. But during evenings in the moshav, the tables turned. We had older brothers we could summon from The Stone.

To break the tedium, some of my friends would throw pomegranates that they picked from trees at the home of an elderly couple, the Frankels. Unfortunately for the Frankels, they lived very close to The Stone. We also exploded detonators and firecrackers, and set fire to potassium from the fertilizer storeroom to watch its blue flame. One time we burned magnesium from an illumination bomb, which we stole from one of our fathers’ ammunition caches. It was unforgettable. For days afterward we all saw black and blue circles every time we closed our eyes, reminding us of the glare.

So everything revolved around The Stone. But on Holocaust Memorial Day—and to be exact, on Yom Hazikaron (a day commemorating Israel’s fallen soldiers)—The Stone stood abandoned. Chinese lanterns, giving off a soft light, decorated both sides of the street from the parking lot to the community hall; these were really just brown paper bags half-filled with sand and a candle. They added a festive aura to the events of the day, and left The Stone bereft of its usual sitters. Although Holocaust Memorial Day was no time for pranks, some of my friends would “accidentally” brush the Chinese lanterns with their feet—not enough to overturn the lanterns, but enough to cause the paper bag to heat up so that in a matter of seconds, as the tripper walked away, it would completely burn out. But that really wasn’t me, only perhaps some bad kid deep inside me. For on Holocaust Memorial Day, the general atmosphere simply wouldn’t allow anything that wasn’t all gravity and tears and awe. The adults didn’t even yell when a kid was caught tampering with a lantern. They wouldn’t scold, only mutter crossly through pursed lips: “You’ve performed sacrilege today, but because of the sanctity of the occasion I can’t be properly cross with you.”

___________________

* A community of farmers.

† From the prayer opening the ceremony.

* Traditionally, the day celebrating both the first harvest of the summer and the Jewish people’s receiving the Torah.

* Meaning member, comrade, or friend.

CHAPTER 3

I acutely remember the unbearable feeling I experienced during one of those ceremonies. For years afterward it would flood back, filling me to bursting whenever I watched Holocaust Memorial Day films, black and white with horrible camera work. They showed naked, emaciated human beings piled on top of each other or stuffed into train cars, or standing in endless lines waiting to be incinerated, shot dead or just plain humiliated. It was in those Holocaust films that I was first exposed to the phenomenon of rape, for they often showed Nazi officers fattening up some scrawny Jewesses in order to turn them into soft, pleasant women. And I couldn’t figure out how the hatred that led to such horrendous abuse and slaughter could exist alongside the love for which the women would be fed and groomed. Sex and the male sex drive were still unfamiliar to me then, so I resolved the contradiction by embracing the explanation I received from my parents and other authority figures: that the perpetrators were Nazis, were absolute evil, and such evil did not make sense the way normal people’s actions did—and if there was no sense, naturally everything was possible.

But that unbearable feeling which I vividly recall from one of those ceremonies—which, perhaps, commemorated the Fallen Soldiers rather than the Holocaust—was as much about me as it was about the gruesome images in those films. It was the tormenting insight that I belong to this one miserable people. Why me? The question gnawed. Why was I born to this fucked-up people? A nation killed and slaughtered and raped as “the whole world kept silent,” as Amiel, our legendary principal with his accordion and moustache and deep sonorous voice, would say at every ceremony in elementary school—and I would always wait patiently for these words, so overpowering, so frightening.

Why do I not belong to another people, any people? Why? I did not yet know, back then, that one could be born an Indian child in a village where drinking water is contaminated by human and cattle waste and the chances of reaching age five are slim. And I certainly couldn’t imagine my mother trying to cure me, her baby, of diarrhea by depriving me of water to dry up the illness, as many Asian women do; in their attempt to stop the watery flow of feces, these women sometimes accidentally dehydrate their children to death. When I wondered why I couldn’t be born to another people, I imagined a perfectly normal place—just like my village, only its inhabitants were not hated or persecuted or killed or incinerated, as in the films shown on Holocaust Memorial Day, or killed in Arab villages on a convoy to Gush Etzyon, lost and helpless.

The tale of the Gush Etzyon convoy belongs to that other Memorial Day, naturally, not to the Holocaust one. But for me they both possess one sense-memory. Not far from my home, some seventy years ago, lived Tuvya Kushnir. He grew up and went to school there, one of my uncontested childhood heroes. Tuvya loved plants (like me) and was “a loyal son to his people, his country, his homeland and village,” as in the lofty lines inscribed on the Bible I received for my Bar Mitzvah from the congregation of the synagogue at my moshav. I too wanted to be a “loyal son to his people.”

Tuvya grew up and became a soldier (like me), and because the Arabs held Jerusalem under siege—literally enclosed it all around with a high fence, a real wall, as they did to the Etzyon bloc as well, so I imagined—those poor people inside had no food or medication or ammunition to defend themselves. Tuvya, my childhood hero, and another thirty-four friends took off on foot carrying food and medication on their shoulders. They couldn’t travel by car because the Arabs who were laying siege to Jerusalem had blocked the roads. That’s why Rabin* and all the others were needed to break through those roads with armored trucks, but that is already another story. As a child, Tuvya would carry two pails of milk hanging from a yoke balanced on his shoulders. When the British soldiers saw him walking like that from the cowshed to the dairy, they probably thought the way I do now about the Indian farmers whom I see passing me by through my train car window. He worked hard as a young boy (like me), and that’s why he was strong and sun-tanned and handsome and ready to carry out the mission to provide food and medication to the poor people under siege. On the way they ran into an Arab shepherd. Since Tuvya and his friends were kind people (they were, after all, sons and brothers of survivors of the Holocaust in Europe, and they didn’t carry on like barbarians), they let the shepherd go, only asking him to please not tell his Arab friends that they were going to Gush Etzyon on a secret mission to bring food and medication and ammunition, just for self-defense, for you know, Mr. Shepherd, what barbaric things your Arab brothers, who are not survivors nor sons of survivors, sometimes do. The shepherd turned out to be a bastard and told his buddies. They killed Tuvya and his friends and probably looted the food and medication—they sure turned out to be barbarians. If they had only learned from Esther, my Bible teacher, that “on the spoil laid they not their hand” … But good luck finding battlefield morals and Bible lore with those savages! Our guys were real heroes, they were few against many, pure against Arab, they fought to the last bullet and died together, loyal, strong, sun-tanned, handsome, pure (like me), and dead—so far not like me—although I yearned with all my heart to grow up and be like them, a loyal son to my people, country, homeland and village. Every year on Memorial Day I would stand and wait to hear Tuvya’s name read among the Fallen of the moshav, and then I would shed a bereaved brother’s tear. We would stand there with everyone else, not with the bereaved families, who were especially honored and had special tears and no one would get cross with their kids even if one of them did “accidentally” trip on a Chinese lantern.

___________________

* One of the siege-breakers in 1948. Almost half a century later, while serving as prime minister, he would be assassinated for seeking a peace treaty with the Palestinians.

CHAPTER 4

In fifth grade I took up the trumpet. In school we were informed of a special fund to help schools in the periphery—that is, in the weaker parts of the country—and that includes us too, not because we’re weak but because we’re far from the center and that’s why we’re entitled. Representatives of this fund came to test our diligence and sense of rhythm by asking us some questions and having us drum on a table. At the end of the test they informed me that I would play the trumpet. I remember this test as something very serious, and yet, when I talked about it at our Sabbath family dinner, my older cousin laughed at me. With one hand he rubbed circles on his belly and with the other, patted his head. When I couldn’t imitate him, he said: “These are at least the skills of a trombone player.” Then he stretched his right hand forward and his left hand back and announced: “Saxophone player.” I joined the general mirth, although it dampened my enthusiasm over the prospect of becoming a trumpet player.

Nonetheless, playing the trumpet started me on a path that would eventually earn me prominence at official ceremonies, which in turn inflated the importance of ceremonies in my mind. There were ceremonies aplenty in our environment—memorial days commemorating the Holocaust, the fallen soldiers, improvised commemorations of Rabin at the public square or at school as one of the “candle kids.”* There were recruiting festivities where the IDF marching song was played in honor of the graduating class leaving the moshav on their way to fulfill their national destiny. Music has the tremendous capacity to amplify feeling, and even when you’re a musician of paltry talent like I was, it’s thrilling to play a part in stirring up the audience.

I distinctly remember the first memorial ceremony where I played the trumpet. It was a total fiasco. IDF Memorial Day is a serious event where not even a snicker is tolerated. So no tomatoes were hurled at me on such a solemn occasion, but still some people bothered to comment: “Something went wrong there when you played.” Or, “Don’t worry, it happened to Ya’ara too when she was just a beginner.” And, indeed, that ceremony signaled the passing of the baton from Ya’ara, the moshav’s ceremonial player—who was well on her way to the army band by then, to play at much larger and more important ceremonies in front of the Knesset or at the President’s residence—to her successor, none other than myself. A few days prior to the ceremony, Ya’ara invited me to her home to choose the songs and practice. When Ya’ara’s name would come up on the playground, kids would mockingly twist their right hand; her right hand was congenitally deformed and she even held the trumpet strangely. But I, six years her junior, was thrilled by her kindness to me and the seriousness with which she undertook the task at hand, as mentor and friend.

We chose “Eli, Eli”* and “Hatikva,”† of course. Most importantly, we practiced the flag-lowering bugle call that would open the ceremony. Ya’ara made up a second part for herself and let me play the lead part so that at the ceremony she could not cover for me. Thus, although she played her second part impeccably, this “Eli, Eli” was outrageous. I squeaked quite a bit through the bugle call, too. At the close of one of our rehearsals, when the ceremony organizer suggested I practice a bit more, Ya’ara told me: “Look, we’re being mocked.” I realized it was only me being mocked. The organizer hinted that I was too small to rise up to the occasion, but Ya’ara really made things easier for me. After the ceremony I felt terrible and didn’t fiddle with any Chinese lanterns. I just wanted my parents to stop chatting with their friends so I could get the hell out of there.

___________________

* Teenagers who lit candles as a mourning ritual following Rabin’s assassination. They were also mourning the passing of the peace process.

* Short poignant invocation of God hailing the simple beauty of creation and expressing one’s yearning for it never to end, written by one of Israel’s pre-State heroes, Hanna Senesh. Senesh was captured, tortured and killed by the Nazis after parachuting behind enemy lines in an attempt to save her Hungarian-Jewish community during the Holocaust.

† The national anthem.

CHAPTER 5

The truth is, my favorite moment in those ceremonies was the announcement that “the ceremony is over,” uttered in a deep official voice, releasing the public from its self-conscious stance at attention for the anthem “Hatikva.” Everyone knows when the singing’s over, the last verse is even repeated—“To be a free nation in our homeland, land of Zion and Jeru-u-u-u-salem”—and then people remain standing for another strange moment, pleasant perhaps but a bit embarrassing, too, until one of the people with the black sheets of paper decorated by yellow Stars-of-David steps gravely up to one of the microphones, inhales deeply, stalls another tiny moment—his moment of power—and says “the ceremony is over.”

My second favorite moment was “Yizkor”*—not the prayer itself but the title. One of the chaps with the black sheets of paper would step up to the microphone. He would wait for a silence that did not always come, for in the back rows people would not have noticed him yet, and some people would still be sitting down, and there would be a kid who had just burnt a Chinese lantern and some mother who crossly, quietly muttered at him, and some dog barking, and again someone would mutter through clenched teeth: “Why do those idiots not tie up their dog? Good God, it’s Holocaust Memorial Day. Even today?” The fellow behind the microphone knew full well that the slightest clearing of his throat would hush the crowd instantly. But usually he does not clear his throat. He would simply say “Yizkor,” strongly emphasizing the “kor,” and then for three or four seconds a deathly silence would fall upon the gathering, even the jackals in the nearby ravine must have realized something important was taking place, and again that “Yizkor,” this time accompanied by “The People of Israel” and so on and so forth. In between “Yizkor” and “The ceremony is over” all sorts of sad, touching texts were recited, snivels were held back, male eyes fogged over, tears flowed down women’s cheeks. In between there were also musical intermezzos meant to move or please the audience.

My trumpet playing made me a vital participant in every single memorial ceremony. Before Ya’ara’s time, however, the flag was lowered on Memorial Days to the sound of the saxophone or even the French horn, and before that, so the legend goes, it was simply lowered to the beat of a drum. Unlike the state flag at the Knesset, the flag at the village was lowered on Memorial Day but not raised again full mast on the morrow, Independence Day, because on Independence Day everyone climbed Mount Gilboa. People used to ascend en masse and play organized games such as tug-of-war, volleyball and dodge ball. There were team games of girls against boys, dairy versus chicken-coop workers, veteran moshav members against new ones. We were the new ones, though I never figured out how this was possible, since I was born there and was already grown up, but apparently a new member remains new for good, and in our parts special honor is due the founding fathers. Eventually, when the social adhesives melted in the heat of the region, and greening-the-wasteland was no longer a noble cause, the communal picnics died out as well. In the spirit of tradition and Independence Day festivities, many still climb up Mount Gilboa to make chicken and beef sacrifices but each family celebrates on its own. These memories of a united community climbing the slope, playing dodge ball and tug-of-war, marching in my mind along with my memory of being stuffed to bursting with grilled meat—I merely mention them here so you might understand how this came about, how we could forget to raise the flag back up on Independence Day. And so our flag always remained at half mast, and still every year we would lower it anew, as if to verify that we still do get very sad. For me this was rather convenient, as the bugle call for lowering the flag was much easier to play than the call for raising it.

The price for not having practiced the bugle call for raising the flag was paid in full years later, in Santiago de Chile, when I was called upon to play during both lowering and raising of the flag. I tried to fake it. The musical director of the ceremony, a respected pianist in the Jewish community, had perfect pitch, and my bad pitch confused her senses. The flag rose slowly, but I didn’t manage to rise in the scale all the way to the high note. It was slightly embarrassing but I didn’t think about it too much, for that Independence Day I was wholly devoted to attempting to lift the skirt of Miriam, one of the Jewish school girls.

Counting Chile (where I spent a nice long time at my uncle’s house), the Czech Republic and Poland (where I went on our high school Holocaust study tour), and Germany (where I went on a youth “friendship mission” from the Gilboa region), I lowered flags and trumpeted the strains of “Hatikvah” in five countries. This was quite a record for someone who did not proceed to enlist in the IDF band. Instead, I put on combat fatigues and become a fighter, moved as I was by the Holocaust Memorial Day and IDF Memorial Day ceremonies. In eleventh grade, when my music teacher told me he had prepared a series of lessons to get me ready for the IDF band auditions and promised that at my present level I would do very well, I sneered: “I want to be a combatant, a fighter. So these preparations are unnecessary.” He tried to persuade me to change my mind. He said that if I chose not to join the band, I had no chance of becoming a musician in the future. “You are giving up everything you have invested in the seven years of your music studies,” he said. “Good,” I answered. “Let’s get on with class.” I enjoyed hearing him declare that this was a significant moment in my life, a moment of decision. It only made me more determined to go running three times a week, six kilometers at a time around the moshav fields, getting ready for the select unit preparatory training.

As an educational activity on Memorial Day, our high school principal invited some lieutenant colonel of the armor corps to speak to us. The lieutenant colonel was a native of nearby moshav Hayogev and an alumnus. The principal’s voice dripped with pride as he introduced the guest, as if he himself had trained the lieutenant colonel to escape anti-tank missiles or had crawled with him up and down sand dunes in basic training. The officer showed us a clip in which a heavy tank stampeded the Negev Desert sands, spitting fire and blasting metal jalopies. At the end of the ride, the tank halted in a cloud of dust and a female soldier emerged from it, taking off her helmet and shaking out her long blonde hair like some shampoo advertisement. This was, as it were, an appeal to the girls, and it was accompanied by an explanation of how they could contribute to the cause as armor corps instructors. But it was also an appeal to us boys, with our hunger for power and sex. What sells better than a slim, tall blonde climbing out of a tank? And not just any tank, but the “world’s best” tank in the “world’s strongest army.” What could be more attractive to an adolescent who could not hear his physics teacher for the sheer flood of nude women performing pornographic dance moves in his mind, filling the space between him and the blackboard?

The lieutenant colonel used allegory to explain our role in the coming years. He described a soldier as a stretcher bearer, nearly collapsing from fatigue but confident that in a few seconds his mate would step up to replace him. Our older friends, now tearing themselves to shreds for three years and bearing the burden of security, were waiting for us to step up as one man and replace them for our allotted time, before getting on with our own lives. I used this romantic allegory myself a few years later to try and motivate my own subordinates. And bidding farewell to my commanders and subordinates, I even made a poem of it, in thanks, for posterity in our company book.

In one of the Holocaust Memorial Day documentary films, someone said that after what had happened in Europe “an armed Jew is sexy.” I don’t recall whose words these were, but they etched themselves in my memory and accompanied me all through my military service. When I was ousted from the pilot-training course, I had some choices to make again. Every “flying cadet” dropped from the course at a late stage is offered a convenient, lucrative home-front assignment. It was easy to relinquish the elitist air force for the sake of becoming an armed Jew. After all, I wanted to be sexy.

___________________

* The “remembrance” prayer.

CHAPTER 6

I began to train for my encounter with you, the girl who stole my Holocaust, when I was ten years old, about your age. Much later my main practice took place in basic and advanced combat training, where I learned to dash from one dugout to another, crawl, aim my gun barrel with a sharp eye and carefully squeeze the trigger, believing in my power and willing to make the greatest of sacrifices. But this was only the final stage of the body and mind training that had started in my early childhood.

In officers’ school too, I was trained for our encounter. This time I learned to make those soldiers you saw following me, run, crawl, and shoot when I ordered them to do so, and always keep their gaze sharply focused for their guns to follow.

There are practice routines that precede certain missions. “Standard operating procedures,” they’re called. Before arresting a wanted man, we would practice the procedure. Before demolishing a house, the men would practice. And lying in ambush was preceded by a tedious and complex briefing. You had to learn how to disappear into the ground so that even if a child rode by on a donkey extremely close to us, he wouldn’t notice us, and if his kid brother came running after him, he wouldn’t spot the change in the topography of his own yard until he literally fell into our superbly camouflaged hiding place. He would then be shackled, blindfolded and perhaps even gently smacked. He would be told that he was out of his mind—he could not possibly have seen what he just saw.

From that moment on he remembered nothing. Total darkness took over and a horrible silence fell all around. He wanted to scream but couldn’t, he wanted to beg forgiveness but knew not of whom. He understood nothing and anyway, no one would believe a word he said. Maybe he better keep it to himself. Do you understand this, little girl?

Prior to such a mission, standard operating procedures were necessary because it was no simple matter to plant a camera facing the window of that grandfather, in whose yard the dark forces of evil assembled. The only possible hideout on that barren rocky hill was underground. We had to reach the exact spot, disguised in advance as that rocky landscape. We had to get rid of our scent. We had to piss, shit and eat in the crowded hideout without leaving a trace. We had to be replaced every twenty-four hours by a new group of soldiers without being discovered. And naturally, we had to prepare for the worst. And the worst, little girl, was a nine-year-old kid running through his grandfather’s yard and falling right into our laps.

The mission in which my Holocaust was stolen was not at all planned, so obviously we had not trained for it. There were no standard operating procedures, not even a concise daily briefing; there was no navigation track to be studied, no gear parade, no briefing on rules of engagement nor possible scenarios of eventualities and responses. However, I had already begun to prepare for it when I was still a child.

In third grade we played a game of “illegal immigrants” against “the Brits.” My father played a principal role in the game: he brought along an authentic Sten gun from Mr. Shem Tov’s weapon collection, preserved in the moshav ever since his Palmah* days. He even brought along a strange balaclava made of greenish-brown wool that had two points jutting out of the sides.

In our game, we pretended to be Jewish underground Hagannah fighters battling the British colonial police. We marched through the darkness towards the beach, where other kids were waiting. These kids played the role of new illegal immigrants to the land that would become Israel. They disembarked, as it were, from their rickety boats. Their faces were the picture of despair. They carried the square suitcases of yesteryear and they all repeated the Hebrew phrase that the Hagannah supreme command had taught them: “I am a Jew in Eretz Israel,” “I am a Jew in Eretz Israel.” We “Hagannah heroes” repeated the same phrase in order to blend in with the immigrants. And so the Brits, the bad guys in this game, couldn’t tell who was a sun-tanned Hebrew-speaking Sabra fighter and who was a new immigrant. These immigrants, coming from faraway places, knew not a word of Hebrew, the language without which the Jews would never be a nation, as was written over our schoolhouse doorway: “Two things without which Jews will never be a nation: the land and the language.”

This was how the Jewish underground fooled the Brits and smuggled in the illegal immigrants who went on to fight the Arabs and made room for us in this country, which was nearly empty anyway to begin with. If the Arabs had not started the fighting, we never would have even needed the war, for we have always sought only peace. Then the illegal immigrants learned the language and this is how we became a nation.

But that was only a childish game. By the time I was ten years old, Jews were allowed to come here and there was no more need to smuggle in illegal immigrants.

Not knowing I would eventually run into you, my little thief, my first real soldiering was as early as the fourth grade—our initiation into night maneuvers in our youth movement. We went out for hag ha’ma’alot, the holiday on which a ceremony of fire inscriptions and torches marks the start of a new year. Every age group would rise up the movement ranks towards the superior levels of counseling and fulfillment, from childhood to youth and on to soldiering in full faith.

Before our first night maneuvers, our excitement knew no bounds. I remember trying on a khaki army belt at home. My mother fit it with a canteen, camouflaged in olive green like the rest of my kit and filled with water. I wore the belt with the canteen over my dark blue shirt, dark enough for night and thick enough to protect me from the thorns we would crawl over while training—“Fall! Crawl! Aim! Range! Fire!” The color blue also stood for simple labor, for we were farmers’ children after all. The shirt was embellished with a red ribbon, for we were socialists as well and believed in the right of every man to equality and liberty. The shirt was tucked into thick blue work trousers that had to be rolled up because they were real adults’ work clothes, and I was short even for my own age.

Evening approached and preparations peaked. For weeks we had slaved over the fire inscription of our group’s name: “Lahav.”* We wrapped sacking around metal wire and dipped it in diesel fuel. Each group prepared an inscription bearing its name, along with another inscription such as “Laavoda, Lahagana Velashalom”: (“For work, for defense, for peace!”), which was the movement’s motto. The inscriptions would be put up at the basalt quarry out in the moshav fields by the older counselors and ninth-graders.

On the night of the holiday the different groups marched to the fire ceremony one by one. The younger kids were told to expect a surprise at the end, and there were rumors galore about what the surprise would be.

We marched uphill on a dirt track. Dark had fallen all around and we walked further and further from the moshav lights, our familiar sense of security fading slowly, replaced by a certain pleasant fear, the kind we knew from galloping on a horse through the moshav fields. We passed by the last goat shed and the old water tower.

“Hey, we’re on our way to the cemetery,” someone whispered, mainly to break the silence and perhaps even to relieve our fear.

“Shhh … quiet!” the counselor scolded us.

“This Yaron can’t take anything seriously,” Jonathan whispered to Michal, as she walked next to him in the line.

Secretly, I envied Jonathan for getting ahead of me, again, with his mature, brave talk. Yaron fell silent. He understood very well, as did the other fourteen kids in the group, that we were doing something serious. The lines marched deeper into the dark. On our left was a citrus grove with its threatening shadows, on our right was a vast field of grain. None of us knew where we were headed. We just repeated to ourselves in silence the orders we had received in our last training session.

At this last training session, our counselor was Kfir, who was not very popular. He was pale and pimply and not the kind of counselor-idol that Elad or Omri were; Elad or Omri were real men who went on to become naval commandos. When Kfir gave us our night maneuver instructions, he said that when we heard someone shout “grenade!” we were to stand still. But his two co-counselors, Hadar and Ella, felt he was making a horrible mistake. The three began to whisper to each other, but then a loud voice shouted, “No arguing in front of the kids!”

We enjoyed the authority crisis taking place in front of our very eyes. Two of the counselors went out to inquire with the elder counselor, who knew about real army stuff. When they came back, Kfir corrected himself. He said that when we hear “grenade!” we should obviously jump sideways and count: Twenty-one, twenty-two, twenty-three, and, boom! Whoever did not lie down in the ditch by the road, curled up with his hands over his head, was already dead for sure. And Kfir added that he knew this, of course, but earlier he had been talking about a lighting grenade—so when we hear someone yell “projector!” we really should stay put like statues, because the British sentries light up the area from their towers and look for movement.

On the real night maneuvers, when we heard “grenade!” we jumped into the thorny bushes. And we stood as still as statues when we heard “projector!” While walking, we kept the proper spacing between us—not so far that we couldn’t maintain eye contact, but not so close as to get blasted by the same explosive charge. When the counselor whispered “count off!” to the kid at the front of the line, that kid quietly passed it on to the next kid, and so on until the count reached the counselor at the back of the line. Then that counselor would whisper “one” to the kid at the back of the line, and the count would eventually reach the front of the line again. Everything was done while walking, and it all had to take place as quietly as humanly possible.

With the years, these counts became simple. Unlike the treks in the army where the guy in front of me would be sweaty and tired. On that first night march I followed a pretty girl and was eager for the next count so I could move two steps ahead, place a secure hand on her shoulder and say “six,” while inhaling some of her body scent. After all, in full daylight I would never dare place a hand on that shoulder: she would see me blush and I wouldn’t know what to whisper to her. And here came night maneuvers to my rescue, making sure that I didn’t get lost in the fields or lynched by an Arab gang or kidnapped by the Brits, and allowing me—ordering me, in fact—to whisper into a pretty girl’s ear over and over again.

After the long trek, we stopped and gathered in silence. We were told that we were to be accepted into the secret fold of the movement, and that the acceptance ceremony would take place on top of a nearby hill. And since the hill was infested with enemies, we would have to sneak up in pairs. Two by two we ventured forth up the hill. On the way we encountered a British sentry with a torch. When the torchlight got close to us we froze as we had practiced, and in the last meters near the top we crawled among the basalt rocks and summer thorns.

At the top sat the secret commanders with masked faces. They read aloud an oath and made us sign it with our thumbs dipped in blood-like gouache paint. We swore to remain loyal and keep the secret and fulfill any mission we were assigned in love and good faith. One by one we swore and then marched together to the fire ceremony. A burning ball descended from the cliff and lit a huge torch, which was passed from group to group. There were greetings and songs, and then came the great surprise, which everyone except for us neophytes knew about already: our parents came there in cars, stayed with us for the ceremony and—special treat—drove us home afterwards.

At one of the youth summer camps I attended—I no longer recall whether it was “In the Footsteps of Warriors Camp,” or “Commando-Underground-Fighters-Against-the-Brits Camp” or perhaps even “Camp of the People of Israel”—I had a special role in night maneuvers. I walked at the end of the line with my friend Ran, who was much cooler and better-looking than I. When the call “grenade!” rang out, we lay down last, facing each other. After waiting on the ground for a long time, we had to make sure none of the kids had fallen asleep—from battle fatigue, or from staying up late to pull pranks, like painting the faces of the girls while they slept or stealing flags from nearby encampments. Ran and I knew we were putting ourselves at risk, but we also knew it was for the good of the whole force. Just like Nathan Elbaz did.

Nathan Elbaz was a soldier who sacrificed his own life to save his fellow soldiers. He was not an admired fighter—his job was to neutralize the detonators of grenades in the bunker tent. One day in the bunker tent, he suddenly heard the worst click of them all—the detonator on a grenade he was holding had somehow been activated. Nathan had four vital seconds to decide what to do. He ran out of the bunker to a nearby ditch, but saw many fellow soldiers there, so he turned back and again saw his beloved friends: Whose life would he sacrifice? He chose himself. He held the grenade close to his chest and jumped on it and died for the sake of everyone in the camp.

This story was often told in the youth movement around Memorial Day or right before a night maneuver. With his death Nathan Elbaz taught us the meaning of comradeship, sacrifice, life. With his death he taught us how to live. I wanted to cry for him but I couldn’t afford to be a crybaby in front of the whole group. On one Memorial Day, our counselor asked us if we would do what Nathan Elbaz the hero did: after all, he could have thrown the grenade far away and then his mates would only have been wounded, and he wouldn’t have been hurt at all. But no, not Nathan Elbaz. He didn’t risk his friends’ lives. He jumped on the grenade.

At that time there were still battle and sacrifice stories mixed up in my mind with tales of vampires threatening to suck my blood. But Nathan Elbaz really did jump over the grenade. His story was real. Unlike the vampire stories, there was no surprise ending that saved everyone from danger. Instead, at the end of Nathan’s story was the question: Would you do as he did? Would you die for our sake? And you?

And you, wouldn’t you want heroic tales to be told about you? Imagine that every year a group of children sat by the spring with their counselor, a counselor in sandals, a blue shirt and shorts, who would tell them fascinating, thrilling stories in which you were the heroine. I did. I wanted stories to be told about me, about my courage, my resourcefulness and cleverness. I dreamt of being a battle hero.

In the meantime, we continued jumping into thorn bushes on night maneuvers and crawling to the flag at summer camp. Years later, this know-how would help me get to you safely.

___________________

* Pre-State commando troops.

* “Blade,” but also “flame.”

CHAPTER 7

Like everyone else, I traveled to Poland with our school delegation. We Jewish Israeli high school students got to visit the death-camp of Auschwitz and other Holocaust commemoration sites as a part of our national grooming, a year before we graduated and enlisted in the military. On the same bus as our group was a delegation from the Israel Air Force technical school, so we had boys in uniform. Throughout the trip, the Air Force flag was flown along with the Israeli flag, all the more impressive and official looking for it.

In Poland, too, I was writing. I wrote because that is what you’re supposed to do—it was healthy and liberating, or so we were told—and also because I wanted to be one of those people who, at Holocaust Memorial Day ceremonies, read out what he himself had written instead of some banal, well-known poem or psalm. And indeed, when we returned I did read one of my writings aloud at both the school and the moshav ceremonies:

I am walking inside the museum at Auschwitz and looking at the piles of shoes. I choose a shoe and try to imagine its owner. Here’s a pink little crybaby girl’s shoe, there’s a dark shoe of a respectable gentleman and pillar of the community. I try to dress those people in the rest of their clothing, and then proceed to give them their shape and gait and a face and eyes and a gaze. I try to hear them talking, but my attempt to imagine an unfamiliar language fails. Here is a pair of large boots, surely of a fifty-year-old man, perhaps even sixty, white-haired, his cheeks plump and his smile broad. A fairly large paunch peeps under an old faded blue cloth jacket, his rough dark trousers held up with a worn leather belt, the pant legs too short so that the heavy boots lying there in front of me show underneath. And that grandfather left his home in town yesterday and was taken here. His home was probably not much different from the houses we saw through the windows of our bus on the way here, a little wooden house surrounded by a garden, summer flowers blooming between the vegetable beds. In winter smoke billowed out of the chimney and a fire heated the small space where his family slept. His children had already left home. One of them went to study at the yeshivah and became a scholar, but the three others learnt a trade and moved to the city, got married and raised children. They have new ideas and don’t ever attend the synagogue. He himself still lives with his wife in the same wooden hut where he was born. Every night as he comes home from the market, where he is employed as a coachman, he stops at the nearby woods to chop some wood for heating. When he gets home, his wife is still working in the garden and the chickens scurry around her, pecking. He unloads the wood off his aching back and they go inside together and have supper—dark bread, cooked barley grits, a chunk of hard cheese and hot tea. This simple, hard, pleasant life came to a sudden halt when this grandfather, who for a few moments is mine as well, was arrested, stuffed into a cattle car and brought here. His heavy boots were taken off, he was stripped, showered, shaved, suffocated, incinerated. His smoke scattered in this sky right here, his ashes thrown into the clear water of the river flowing nearby. This is how I went on and scanned many pairs of shoes, and created people, and invented their lives.

In Poland I was proud and happy. The piles of shoes and ash at Auschwitz and Maidanek, and the stories of the witness who accompanied us (who had been one of Dr. Mengele’s “children”), the descriptions of starvation in the woods—all these are not exactly a recipe for happiness, of course, but still I was happy.

At Auschwitz I wept as I read the names of all the Labendiks who had been killed. Labendik was the name of my paternal grandfather before he changed it to the Hebrew name Chayut (vitality)—a rather absurd name to bear in the death camps. I wept at the hall with its commemorative candles and sang the kaddish, the traditional Jewish prayer for the dead, in a deep sad voice with a list of names in my hand. I burst into very real tears and wept for a very long time, a loud, visceral, unstoppable weeping. It was the first time I ever read this list that we were asked to bring along and my mother had prepared for me before we left. It was photocopied from the town register of Sokolka. What a horrible list: names and names and more names, truly depressing.

I had not worked on a roots project in the seventh grade, not even copied my sisters’ projects, as did many other third sons of deep-rooted families. I was lazy, just as I was too lazy to photocopy that list myself or at least give it a glance before our departure, and that’s why I didn’t know how large my family had been. And perhaps, too, because my grandfather passed away long before I was born and my grandmother did not even live long enough to celebrate my father’s Bar Mitzvah, and so I had no one to relate that huge murdered family to. But that shocking list removed all the brakes and opened my floodgates. Only now did I realize that out of so many, only my father and one aunt—his sister—were left, and that we seven cousins would have numbered dozens or even hundreds of people.

The anger, the sorrow, the shame and the unwillingness to be a part of all this—the emotions I felt towards my Holocaust when I was a young child—were now replaced by entirely different emotions. Now, in Poland, as a high school adolescent, I began to sense belonging, self-love, power and pride, and the desire to contribute, to live and be strong, so strong that no one would ever try to hurt me.

I remember the tones of “Hatikvah” as I played my trumpet in the death camps of Poland, and a year earlier in the German concentration camp at Buchenwald, which I visited with a German-Israeli friendship delegation of youth—the strongest sensation I had had back then was the desire to take revenge.

As I played I took revenge on all those who hated us. If any Nazi villain, I thought, is hiding in Argentina or Brazil, if some miserable train worker of that war is now sitting in his living room in Germany or Poland, he is surely going crazy at the thought that in spite of all the extermination efforts, our State has come into being. A whole nation was gathered from all corners of the earth to the land of its forefathers to found a mighty army and build national waterways and highways, and glass skyscrapers in Tel Aviv. And that nation sent me to the country of this Nazi villain to play our national anthem, full of hope—tikvah.

Wherever they might be, those scum-of-the-earth criminals, they were now tormented by my vengeful playing, our vengeance in being proud Jewish boys, a vengeance mightier than any court sentence, more painful, even, than the hangman’s noose. That melody echoed in the ears of our haters and proved that in spite of the registers of the victims that we read, weeping, and despite the ashes of all those who were incinerated, and the piles of shoes and spectacles and gold teeth pulled out and shipped directly to Switzerland, in spite of it all, we were strong. And I was here and I was blowing the trumpet D-E-F-G-A-A for “Hatikvah” and B-B-F#-G for “My God, my God, may it never be over / The sand and the sea, the rustling water / The glittering sky, man’s prayer.”*

This was sweet revenge. I drew power from my Holocaust and this power pushed me on, to want to enlist and serve in a select recon unit, possibly in the Nahal, for my dad served there and that would strengthen my roots. (And also because there are fewer bullies in the Nahal and my time there would be more fun.) But this is only in parentheses because frankly I am all for integration, and a melting pot the likes of our army exists nowhere else in the world.

This was the force that later pushed me to go to officers’ training at the end of my training as a combatant. Other options of assignment made by my commanders were tempting and even flattering and much in demand, and I wasn’t exactly one of my team’s favorites, to put it mildly. And rightly so.

I was one of those who told on the commander who cheated on exams and who opened a map during navigation maneuvers. I had been instructed that “credibility and truth are foremost in the army,” but I never realized they didn’t really mean it. Even years later, when I would join Breaking the Silence and would tell anyone, any journalist who listened, how houses were blasted and what it was like to use a human shield and how it felt to command a dozen soldiers and 2,500 Palestinians on a normal “workday” at Qalandiya Checkpoint—even then I would still think that credibility and truth come first.

It would take a long time for me to gradually realize that for many people, truth is worth nothing. When I realized this I was deeply disappointed in human nature, just as I felt when, as a child, I discovered what rape was and was ashamed of being male, and just as I felt when I discovered how many guys cheated on pilot training exams. There were only a few nerds who watched their ass and they didn’t really mind what the others did. When the squadron commander arrived to deliver a speech about credibility and warned us not to cheat, I wondered whether he had once been one of the few nerds and not like all the rest. Suddenly, I didn’t believe him. I got sick to my stomach and cried that night, cried like a kid on the shoulder of my buddy, the other nerd in the course.

I cried because I missed my girlfriend, and because of the lies. Everyone lied. Even I lied. I had lied to her two years earlier. I had gone as a “young ambassador” to represent our country in Argentina and Chile. I told them what a cool place Israel was and that they shouldn’t listen to the news about us because everyone lied and we in Israel only wanted peace, and that boys and children were the same everywhere, maybe except for those in countries where they are brainwashed and it was not their fault. There, in Chile, I kissed the daughter of the man in charge of education in the region. We even made out in the back seat of the car, when her father drove us to our next destination. And now I was crying because I hadn’t confessed this to my beloved, my girlfriend who was not waiting for me at home like she did two years ago, loving and loyal, and I was a wretched liar like everyone else. What a crisis that was. The irony is that the friend on whose shoulders I cried would wait not even twenty-four hours after I broke up with that love of my youth before he took her under his wing and invited her to cry on his shoulder—not just any shoulder. It was the shoulder of a pilot, a tall and handsome pilot.

I was sent on this mission to Chile and Argentina on behalf of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs when I was in the eleventh grade. We traveled in couples as “young ambassadors” and stayed overnight with host families, mainly from the Jewish communities but also with families of non-Jewish Zionist supporters. We spoke at schools, universities, youth movements and even at one Christian church. We projected an official silent PR film and spoke of our country’s beauty, sanctity and uniqueness. We said that in our country new drivers tagged their car with a yellow sign so everyone would know they couldn’t drive very well yet, and this always made our audience laugh. We would show the audience this “new driver” sign and use it to demonstrate the special Hebrew alphabet, which we said was written from right to left. We wrote our names on the board and even the names of a few people in the audience.

The most amusing part for us was to explain our country’s miniature proportions, as we fitted its whole length into the width of narrow Chile. Or all of it into the tiny province of Tucuman in Argentina—they simply couldn’t believe it. We amazed them by telling them the obvious: that as Deborah, my fellow traveler, explained, “Soon we will enlist, he for three years, I for two,” and added how important it was for us to contribute to our country, and how normal and obvious it was for us that the army was the next phase in our lives, after school and before the “big trip” and college.

At every lecture we gave, Deborah and I raised the topic of the Holocaust and its inevitable lesson: that our country, the State of Israel, must exist and be strong. The idea of talking about the Holocaust was mine, but Deborah played the principal role in this show. At times she made the audience weep as she told about her survivor grandmother who could not possibly throw away food, not even a single crumb, and forced the whole family to eat everything on their plates, down to the last morsel. And if there were still leftovers, she collected them and ate them herself or saved them for the next meal. Before one of the lectures I suggested she let up a bit, and in this spirit I even changed our usual commentary during the film. She was very cross at me and for nearly two days we hardly spoke to each other.

Slowly, the telling of the Holocaust became our mission’s main topic. I recall how one evening, in the province of Misiones, Argentina, I touched the heart of the mother of our host family. We spoke about the Holocaust and the refugees who arrived on a rickety boat from blood-drenched Europe and immediately went forth to fight the Arabs. I described in detail the myth of the Jew who migrated to Palestine on his own, without any family relations, disembarked in Jaffa port, was handed a gun and ran east to fight for Jerusalem and fell there on one of its rocky hills, and now he is buried nameless, and has no one to mourn him or honor his memory. That is why we as a nation must mourn and honor this refugee, whose force and valiance all of the seven Arab states together could not defeat. I spoke about the successors of this refugee in Israel’s subsequent wars, and when I got to 1967—the conquest of the Wailing Wall, the unification of Jerusalem and the nation’s broken heart—her tears flowed. Tears that must have already sprung earlier when she thought of her father, how he sailed alone to Argentina at the end of that war, and but for his luck, he too might have reached Jaffa and run on from there to some Jerusalem hill, and then she would not have been born, nor would her large house exist, neither her great wealth nor her daughter, about my age, who sat at the table throughout this conversation, completely bored.

And so my brain—washed with a single dogmatic truth—combined with my youthful innocence and my skill at moving hearts made tears flow in faraway Argentina. I kept those tears in my memory along with the tears I gathered while reading aloud what I had written about the imaginary grandfather in Poland. The next tears I proceeded to reap were tears of the love for homeland and flag, tears proud and uplifted, tears of rich Jews and very rich American Jewish mothers and grandmothers, tears falling on checks and contracts for investments in bonds, which we collected every evening.

But that chapter of my story will have to wait. First, as I promised, I’ll tell you about the girl who stole my Holocaust.

___________________

* “Eli, Eli.”

CHAPTER 8

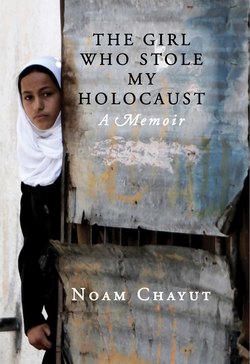

I don’t know the name of the thief, but her image is deeply etched in my memory. Her complexion is lighter than that of her fellow villagers. Her eyes are black and large, set off by long dusty eyelashes. Her height is that of a ten-year-old and she is thin, very thin. Her shoulder blades protrude.

On the day of the theft, she wore a light-colored garment that I can’t exactly describe, but I remember how, at the moment of the deed itself, when she finally looked away and began to run with her back to me, it fluttered against her bony body. The air was still on that hot, hazy day on the northern slopes of the Jerusalem hills. And yet that light-colored garment billows in my memory. Seeing her run was a familiar sight and seemed almost natural, so I realized very late that this child had run off with the most precious emotional and spiritual possession I had inherited from my forefathers—my Holocaust.

I didn’t know your village, my little thief. It was not one of those “wasps’ nests”—that is how we referred to the “hostile” or “trouble-spot” villages that we frequented in order to “make a show of presence.” This meant rumbling through them, raising a racket, hurling teargas canisters into markets and balconies, blasting stun grenades, amusedly yelling swearwords over the commander’s Jeep loudspeaker, firing live ammunition at house walls, piles of dirt and trash or vineyard terraces. I knew such villages like the palm of my hand.

I knew where stones would be thrown and where I could walk about safely, smiling, without wearing a helmet. I knew where a Jeep could be parked without being noticed and where passers-by could be taken by surprise at our show of force. I knew where we mustn’t enter because exiting that alley would take too long and the stone- and stick-hurlers would have plenty of time to jeer as we remained caged in our Jeep.

“I am no sucker,” the first Israeli I met in India, at the New Delhi airport, told me. “I let myself be screwed once in every country and then, then I learn my lesson and it never happens again, no way!” He was on his way to see his regular yoga teacher to calm down a bit. And he really needed to calm down, who doesn’t? That’s how it was in the Occupied Territories, too: I was no sucker and if I got screwed once with a hail of stones, sticks and curses, fine. Once, I entered that street, and it was a mistake that someone had to pay for; someone always pays for those first, one-time mistakes. For example, a kid paid for running slowly while trying to escape chaos. He was caught and shackled in front of his mother or older sister, who screamed and wept, and he was thrown into the Jeep, driven an hour’s walk away, then lightly pushed out of the Jeep. I don’t remember whether we freed his hands or let the other price-payers do it. Anyway, we figured, this kid learned his lesson.

And it was not only kids who were there to pay for the humiliation we felt after making such mistakes. Shopkeepers, too, paid when we fired teargas into their shops because we thought the curses or stones had originated there. Or their name was very similar to one of the names on our wanted list. Or their shop was on Shaheed Street, and Shaheed, we all thought, means terrorist, so it makes sense that on “terrorist” street we’ll find the guilty parties who must pay for humiliating us.

This was all done in order to “make them pay the price for disturbing the peace”—these were the exact words used in written orders when the authorities wanted to define the need for scapegoats. These orders needed to be confirmed by the upper echelons, but that did not mean that we always had to use gas canisters to make our point clear. We could just park the armed personnel carrier or Jeep in front of the shop and eat our warm meal there, brought along specially for this mission. Hear some music, have a good meal, if the right cook was on the right shift. And also “show presence.” The shopkeeper would beg us to go enjoy ourselves elsewhere, because otherwise no customers would come in, and he hadn’t earned anything anyway since that whole shit began. Interesting, what he meant by “since the whole shit began.” We had been in that area only two or three months and it smelled as though the shit has always been there … “You should have thought of this before you let them hurl stones from the roof of the apartment above your shop,” someone would tell him, while chewing some mashed potatoes or a meat patty. While the shopkeeper begged, flattered the soldiers, and cursed Arafat and the rest of the PA leaders, he also carried out our mission impeccably. He shooed away any boy or child and yelled at the youngsters running on the rooftops and sometimes even caught someone who may have been there yesterday and beat him to a pulp, beat him up as we never would. After all, we are no Arabs.

Her village was not like that. So in spite of its proximity to our camp, I wasn’t familiar with the place. The village vineyards bordered on the camp and we only had to drive ten minutes to enter: exit the camp to the main road and cross the barbed wire “barrier.” “Barrier”—the official appellation of the Separation Fence when it was first erected. Sometimes the barrier consisted of a mere pile of barbed wire coils—“curlies”—which were sometimes used for stage sets in Holocaust Memorial ceremonies. At other times the barrier might consist of a pothole, or a ditch dug in the rock, or a dirt pile. Our mission that day was as simple as could be: “escorting” civil administration officials.

Such escorts were usually easy and uneventful. But they sometimes included interesting encounters with “special forces,” such as police officers sent to search for stolen Jewish property in Palestinian towns; or Shabak General Security Services agents who spoke very little and always wore tense, impressive faces, their weapons—incidental as they were—shining under their dark jackets. We also escorted Engineering Corps units who sampled the bedrock, and waterworks employees who searched for water or planned pipeline routes, or employees of cellular phone companies and private contractors sent to put up antennas or connect residential trailers of Israeli settlers to the power grid.

We also escorted senior army officers who for some reason never followed the orders they themselves had issued and wouldn’t let us check the area before they rode through in their less-armored cars, so that our escort really had nothing to do with their security. They looked on with contempt, always, and we were especially amused to see how our tough, cruel deputy battalion commander would scurry around them like a chicken and explain and apologize in an unfamiliarly patient tone and note down their scolds and reprimands in his book as though these were direct orders to be promptly carried out.

Thus our commander faced the general, as I faced him and on down the chain of command, down to the child who was too slow to run away and would pay for the humiliation suffered by the legendary deputy battalion commander as the general scolded him in front of his subordinates.

Anyway, the escort on that day was as simple as could be. Civil administration agents arrived to survey land in various places and they were always delighted to tell us that this or that block of land was state land that the villagers had poached, or land that had been purchased by a very rich and generous American Jew who tricked the Arabs and promised them he’d build a gas station on it, and they naturally didn’t know he was a Jew and sold it to him. And now he wanted to transfer ownership to a yeshivah and so trouble might be brewing in the area. “But we of the civil administration are here only to survey the plot of land itself and pass on the maps.”

On such occasions, “locals,” as they were called, often materialized out of the fields or houses, wishing to present documents to the administration people or the “officer in charge,” which in their jargon meant the supreme authority in the region. And then, often, some passing sergeant or one of the soldiers would present himself as the “officer in charge” in order to wave off the villager, because the real officer was busy or simply didn’t feel like speaking with the Arabs. Once, “locals” showed up wishing to speak to the “officer in charge,” namely myself. And they waved and showed all kinds of maps, documents, writs of ownership dating from the Ottoman Empire. The papers were colorful and decorated with official Turkish stamps, which in their opinion was ample proof of their claim to the land. The father of the family approached me. Like any other chance “officer in charge,” I was not authorized to read Ottoman maps. What do I know of property laws? Perhaps I don’t even know of their existence? Who even decided them? And what have they to do with me? What do I care whose land this is? What business is this of mine? After all I just need to ensure the well-being of the fellow who is here to survey this plot of land and pass the map on to whoever ordered it made and paid for it and will build whatever he will on it.

But this particular escort was not meant for surveying land, preparing a map or marking the route of future construction. The officials had come there to post paper notices on olive tree trunks. And this was the content of the notice, more or less: This area is confiscated by the State for security purposes according to such and such regulations and by force of this and that law. Owners of the area may appeal within the time frame allowed by law to the legal authority set by the same law or regulation or edict or …

I don’t recall the exact words, of course, but I do remember that even then it seemed ridiculous to post such notices on the trunks of centuries-old olive trees that did not speak Hebrew, and anyway they had been planted there long before laws and regulations and edicts had been issued in Hebrew in this country, at least this time around, and if an olive tree were found that was old enough to understand, its owner certainly wouldn’t, and even if he did, he would not be allowed to cross the checkpoint in order to appeal to the proper legal authority. At any rate, the official, wearing sandals, jeans and a light striped shirt, looking so out of place in this dusty landscape, took out a camera and photographed the grove and the trees with the notices posted on their trunks.

Then we escorted the civil administration vehicle to the main road. This time we passed through the village itself and not through the barrier. I don’t remember the reason for changing our route, perhaps the road was especially rough and dangerous because it had not yet been completed. For some reason, I recall stopping on our way, at the village outskirts, where I opened the Jeep door and “stormily” disembarked—and here, my little thief, I must digress: the term “stormy disembarkation” is etched in my memory ever since my Jeep appeared on Israeli television news. It was in Ramallah’s city center that we once stopped TV reporter Uri Levy and his film crew. This was during Operation “Onward Determination,” or perhaps it was Operation “Here’s to You”—one of the two. I yelled at Uri Levy that “this is a closed military zone,” and we had our hands full as it was, chasing foreign television networks and we didn’t really have time to waste on Israeli TV crews. He was startled, and said they had already received orders to clear out and were on their way when we stopped them. Later, when he calmed down, he smiled and complimented us on our “stormy disembarkation.” I very much hoped it would be broadcast on the news, because I found it very impressive indeed.