Читать книгу Noel Merrill Wien - Noel Merrill Wien - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

The Early Years

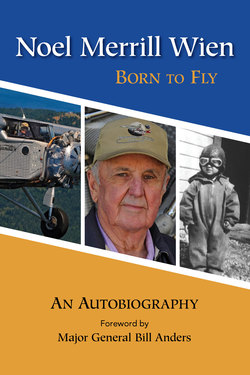

In May 1930, there was a picture of my mother and me on the front page of the Minneapolis-St. Paul newspaper, stating that baby Noel Merrill Wien “lays claim to having the most flying time of any ‘aviator’ his age in the United States.” I was eleven weeks old and, lying in a wicker clothes basket, had been flying in a 1930 Stinson with my mother and dad all over the Midwest, visiting air shows and airplane manufacturers. I suspect that my interest in aviation began at that early age, probably through a vibration osmosis from the plane, which my dad had recently purchased to take back to Fairbanks, Alaska, where we lived.

My father was already well known by this time because of his exploits flying in Alaska and his visit to Minnesota, the state where he grew up, was big news. When he arrived in Alaska in 1924, there were few airplanes flying there. Since that time, he had completed the first airplane flight between Anchorage and Fairbanks, the first round-trip in an airplane between North America and Asia, and the first one-way flight between Asia and North America. He also made the first flight north of the Arctic Circle anywhere in the world, as well as many other first flights within Alaska. He did not know he was making history at the time. He just loved to fly and was determined to make a living at it.

My younger brother, Richard, and my younger sister, Jean, and I were not really aware of my father’s fame when we were growing up. He was just fun to be with and he seemed to be well liked by everyone around us.

I loved hearing about the flying experiences of other pilots we encountered in our daily life. My dad did not talk much about his experiences unless he was asked a specific question.

When I was about five years old, I remember asking my mother, “Am I ever going to grow up?” She said, “All too soon.” I have thought about that day, which seems a very short time ago, many times. I was in a hurry to grow up because I was living among airplanes and pilots and I wanted to be a part of that exciting world. I could not wait to get my hands on the controls.

I always looked forward to Dad returning after he was gone for several days because he quite often brought me a present, usually an airplane that the Natives from the outlying villages had carved. I never expected a present other than a toy airplane. I made my first model airplanes out of toothpicks and tissue paper. Eventually, an older friend in the neighborhood, Frank Conway, was kind enough to teach me to build with model airplane kits and to show me how to fly them. In those days, the power models flew “free flight,” meaning they were trimmed to climb making left turns with the help of engine torque and when the engine quit, they would descend in right turns minus torque and hopefully land not too far away.

Later, I got into control line flying. The ignition on the gas engines operated with two flashlight batteries, a coil, and a condenser, which provided spark plug ignition through points that opened and closed on a cam on the crankshaft. When the engine would not start it was usually due to no spark. When this happened, I often persuaded Richard to put his hand on the spark plug to see if there was any spark. When he resisted, I told him that if he didn’t do it, he could not watch me fly. He finally figured out that I had no way of preventing him from watching. As he got older, he blamed his hair loss on all of the electric shocks I forced on him.

One of the best things about airplane-crazy kids having a pilot for a dad is that we ended up with old airplanes in our backyard that provided endless hours of fun and fed our dreams about someday becoming pilots. The first old plane was an Avro Avian biplane that my dad’s good friend Robert Crawford had crashed. Somehow my dad ended up with it and even though he had the Wien mechanics rebuild it, he never trusted the splices in the fuselage enough to fly it. So Richard and I got it.

Then when I was around twelve years old, my brother and I talked the owner of a Kinner Bird biplane into selling it. It had been sitting at Weeks Field for years and was complete except for the engine. We paid five dollars of our hard-earned allowance money for it. What a find that would be today. As I remember, the wings had been removed and were lying alongside the airplane. We didn’t even bother to take them with us. As we walked home pushing the fuselage, a policeman stopped us and asked where did we think we were going with that airplane? We had to stay there until he verified the transaction from the seller. That Kinner powered Bird provided us with many good hours of simulated flight, but in time we decided to remove the fabric and cover the bare fuselage with canvas and make a boat out of it. We lived near a slough and longed to get out on the water. That plan didn’t turn out too well. But, always full of new ideas, I decided I would convert the fuselage into a helicopter using the old Avro engine that was stored in the Wien hangar. After I finished drawing up my plans for the helicopter, I showed them to my dad. He acted very impressed and told me that he thought it would fly. Encouraged by his comments, I went to work but eventually I ran into structural and design problems and aborted the program due to lack of funding. My twenty-five cents a week fell short on costs. I sure wish I had that rare airplane now.…

AS I GREW OLDER, IT DIDN’T TAKE ME long to figure out that the gasoline engine could open up a whole new world for me. In the back of the Pacific Alaska hangar, there was a dump where they discarded old airplane parts and my friends and I would scrounge through it looking for construction material. One day we discovered a motorcycle frame with an engine still attached. We unbolted the engine and dragged it home in a little wagon.

Inside a tent in the backyard, I was busy dreaming up plans for how to use the engine when a stranger appeared at the tent opening. He was searching the neighborhood for his missing engine and was giving me a good chewing out when my mother heard the commotion and came out of the house. She did not like seeing her son being verbally abused and gave the man a tongue lashing in the way only a mother could do. He took the engine back, but a few days later I found a small 5/8 hp engine sitting on the front steps. I guess the man took pity on me and saw that I was simply a curious kid. It did not have much power but it was self-contained with the fuel tank in the frame and it ran perfectly.

Anything motorized caught my attention. A close family friend, Joe Crosson, built a small go-cart for his sons with a Maytag gas-powered washing machine engine. It was a masterpiece of engineering. Day after day, Joe allowed me to share it with his sons on the Pacific Alaska Airways ramp at Weeks Field, giving me a thrill that I was able to drive a “car.”

I figured out another way to benefit from motorized transportation. When I knew that my father was due home from the airport, I waited for him with my bike at the corner of our block and intercepted him on the road. He would slow down and let me put my right foot on the running board of our 1941 Studebaker while I hung on to the door sill with my right hand, steering the bike with my left. That was the only way I could figure how to motorize my bicycle. Sometimes he would go around the block to give me an extended ride.

As I grew into my early teens, my father let me drive the Wien Airlines tractor that they used to tow airplanes. When we used it to landscape our yard, my younger brother and sister would hang on to the drag as I towed it and it was great fun. In later years when I worked for Wien Airlines after school and on weekends, they let me tow airplanes with that tractor. It was all part of my learning and I’m sure my early interest in all things motorized helped me when I began learning to fly.

In the years that followed, I yearned for motorized transportation of my own. I finally determined that if I were ever going to have a car, I had to build it myself. I scrounged airplane parts from the Wien hangar—wheels, tail wheel forks, steering wheels, and tubing—and talked the mechanics into welding the different parts together. For the pulley that I needed to mount on the drive wheel I bolted two pizza pans together. I scrounged a V belt from an old car and installed the 5/8 hp engine that had been given to me. I guess you would call the transmission a direct drive system. I built about three go-carts and they all ran, if only for a short distance.

MY FASCINATION WITH AIRPLANES CAME NOT ONLY FROM having a well-known aviator as my father, but also from my exposure to the pilots and flights that passed through Fairbanks, an aviation crossroads at that time, throughout my childhood. When world renowned pilots and airplanes would arrive in Fairbanks, most of the town, including my family, went to the airport. It was an educational experience for me to see these different airplanes and hear about their missions.

When I was about eight years old, I remember meeting Robert Crawford, the composer of the Army Air Corps song, and sitting on the floor next to the piano, watching him bang out “Off We Go” so loudly that I had to cover my ears.

The first Army airplanes—two Douglas O-38 biplanes—arrived at Weeks Field in 1934 to survey Alaska for an Army airfield location. President Roosevelt was concerned that Alaska might be vulnerable to attack, but this was still a time when the Navy’s viewpoint about national security held sway; battleships were considered more important than air power. For years, General Billy Mitchell had tried to convince the military that airplanes were critical to national defense and he made this point so strongly that he was later court-martialed for insubordination. In 1925, he had even forecast that someday the Japanese would attack Pearl Harbor from the air, and this, of course, is exactly what happened. The Japanese paid attention to General Mitchell and so at the beginning of World War II, they had more airplanes and aircraft carriers than the United States. It’s too bad we didn’t listen to him. Shortly after the O-38s, Major Hap Arnold arrived with ten Martin B-10s to prove the capability of the Air Service as they continued to push for more emphasis on air power.

In 1935, I was playing with my friend Earle Grandison, and we saw Wiley Post and Will Rogers flying over Fairbanks. Their plane was a Lockheed on floats, which was actually assembled from parts of two different Lockheeds. Wiley had installed a larger engine with a heavier than usual three-bladed propeller, making the plane very nose heavy. It probably never should have been certified. I accompanied my parents to watch their arrival on the Chena River, right about where Ladd Field (now Fort Wainwright) was later built. This was just a few days before Post and Rogers were killed when their plane crashed near Point Barrow. My father ended up getting involved in this piece of history as he made a historic flight, racing against another pilot, to deliver the first photographs of the crash to the news outlets in Seattle. After flying all night, my father got to Seattle first, beating the other pilot by two hours.

Howard Hughes arrived in Fairbanks in 1938 on his record-setting flight around the world. At the time, his stop in Fairbanks did not have much significance for me other than the fact that I was impressed by his big, beautiful airplane. But now when I look back at the memory, I realize that I witnessed a historic flight by a famous pilot. I then remember some Japanese pilots arriving in 1937 in a Mitsubishi G3M bomber, supposedly on a goodwill trip. I heard a bystander say that they were probably there to survey Alaska. It didn’t mean anything to me then, but it’s funny how you remember these things years later.

MY PARENTS NEVER ENCOURAGED ME TO BE A pilot. I suppose my dad recognized that my enthusiasm was obvious. I don’t think my mother wanted me to be a pilot but she never discouraged me. She had lived through times when my dad had been overdue for weeks and she hadn’t known if she would ever see him again.

I was so fortunate to have been able to experience the thrill of flight at an early age. Though I preferred to fly with my dad, I jumped at the chance to fly with anyone who would take me. But I remember coming home, excited to tell my dad about a great flight I had with someone else, only to be scolded about flying with someone he didn’t know. Not everyone was as safety conscious as he was and he wanted to be sure I flew only with people whose flying abilities he trusted.

When people talk about the good old days, believe me, they really were the good old days. I have owned many different airplanes during my lifetime but as the years passed I began to look back at the airplanes of the 1920s and 1930s with a great deal of nostalgia, partly because those were the airplanes my dad made history with. Newer airplanes were more efficient in speed and comfort but I would love to have been able to fly more of the planes my dad flew. The early Stinsons, Travel Airs, and Fairchilds seem to have a personality that is not found in modern airplanes and I will never forget the distinct vibration and sound of those old planes, and the way they smelled of adventure and excitement.

I vividly remember riding with my dad in the Fairchild 71, Travel Air 6000, or Cessna Airmaster on floats as we departed Fairbanks on the Chena River, which runs through downtown. At that time, the Chena was the only waterway near Fairbanks for float operations but it was a fairly dicey takeoff location. People would gather on the riverbank when they heard the engines start. It was impressive to watch.

Before starting our takeoff, my dad would taxi upriver to the usual starting point under the Cushman Street bridge. After he turned the plane around and throttled up for the takeoff, it always looked like the propeller was going to hit the bridge as the nose came up before getting on the step (planing on the water). Then it would look like we were not going to make the first turn in the river, which was quite sharp. I always thought the left wing was going to hit the high bank by the Northern Commercial company store during the right turn before reaching the straightaway for the anticipated liftoff. Sometimes if we had a heavy load in the plane, my dad would have to make one more sharp turn to the left on the water. This was always a terrifying experience for me but I never turned down the opportunity. I think it was a safe operation because most pilots knew their airplane’s performance capabilities and they were confident in their abilities, but it was still scary when you were sitting in the cabin during takeoff.

When I was about ten years old I thought I had my big chance to fly an airplane. I had flown with my dad in the Tri-Motor Ford many times but seldom in the cockpit. Usually, my uncle Fritz rode along to function as a mechanic and to help with the loads so I was relegated to a cabin seat. This time, my dad was doing a test hop without Fritz so I happily climbed into the cockpit’s right seat.

The Tri-Motor’s brakes were controlled by a gearshift-type lever between the seats, commonly called a Johnson bar. Pulling the lever straight back applied the brakes to both wheels; moving it to the left or right provided differential braking. Because the brakes were not on the rudder pedals, a pilot needed three hands to control throttles, brakes, and control wheel. So the technique was to use the right hand for the brakes for ground steering and the left hand for the throttles on takeoff until directional control was available with the rudders. When I saw that the control wheel was unattended, I was certain that this was my chance to do the takeoff so I grabbed the wheel. Everything was going fine until the rudders became effective, whereupon my dad transferred his left hand to the wheel and the right hand to the throttles. Then it was time to raise the tail; when he pushed the control wheel forward, it was pulled out of my hands, but not without some effort since I had a firm grip on it. I then realized that I was not going to get checked out in the Ford that day. The fact that I could not reach the rudder pedals did not concern me; they looked like footrests to me.

Somewhere around the early 1940s, I had the opportunity to fly to Anchorage with my dad in a Travel Air 6000A. He had purchased a set of floats from Bob Reeve, founder of Reeve Aleutian Airways, and was taking the Wien chief mechanic, Ernie Hubbard, to install the floats on the plane in Anchorage. Airplanes were still somewhat of a rarity in Alaska at that time so when we arrived, there were only two floatplanes on Lake Spenard—one belonged to Bob Reeve and the other belonged to Art Woodley, founder of Woodley Airways, which later became Pacific Northern Airlines. (Many years later I was driving with my dad in the area and we saw hundreds of floatplanes parked side-by-side all around Lake Spenard and neighboring Lake Hood. Hundreds more were parked on wheels on land. He said, “Never in my wildest dreams would I ever have thought that I would see this many airplanes here.”)

Spenard Lake was linked to Lake Hood by a recently built canal. Both lakes were limited in size and the new canal provided a longer takeoff area, enabling airplanes to take off with heavier loads. We landed alongside the canal on a new landing strip. Ernie installed the floats on the plane and then it was hoisted into the canal and we prepared for takeoff. Try as he might, my dad could not get the Travel Air on the step; he just didn’t have enough power. Bob Reeve offered to lend him a longer propeller, more suitable for float operations. That did the trick and we were on our way to Fairbanks. I remember that my dad had to work the rudders all the way to Fairbanks because the floats caused quite a bit of instability around the yaw axis. After arriving in Fairbanks, Ernie added a fixed rudder under the rear of the fuselage, which was a big help. On each one of these trips with my dad, I watched him handle the controls, saw the results, and learned a little bit more.

When I was around twelve years old, I was convinced that I had it all figured out and longed for the chance to fly. My dad rented a Piper J-3 Cub at Weeks Field in Fairbanks and this became my first opportunity to do a takeoff in an airplane. I was anxious to demonstrate my flying ability to my dad as he sat behind me. I managed to get it into the air, probably with some help that I was not aware of. I flew around for a while and then it came time to make a landing. I managed to get lined up with the runway and thought this would be the easy part; however, the ground came up much faster than I expected and it was a jarring experience. The airplane was fine but my confidence was severely damaged. I learned then that my dad’s approach to teaching was to sit quietly and do nothing to help me unless he thought that intervention was needed to avoid bending the airplane. One time when I was about fifteen years old, we rented a surplus Boeing Stearman at Paine Field in Everett, Washington. I thought my takeoff was going well until I felt the rudder pedals moving rapidly to avert a ground loop. I had no idea that I was about to lose control.

My experience in the Piper Cub set my confidence back for a while and gave me a lot to think about, but it didn’t affect my desire to learn to fly. I wanted to be a pilot like my father. His fame as an aviation pioneer was well recognized but for me and Richard, his talents as a father dominated our admiration. He always tried to help me achieve my dreams, whatever they were. I was immensely fortunate, also, to have my younger brother, Richard, who was as anxious as I was to follow in our father’s footsteps. We shared our love of flying throughout our lives. In addition to being an exceptional pilot, Richard’s vision and analytical talent have always amazed me.

FLYING IN ALASKA WAS ALWAYS A DANGEROUS AND difficult business. My father had left Alaska in the fall of 1924 because winter operations were not possible with the airplanes available at that time. When he returned for the summer season in 1925, he brought his brother Ralph with him. He taught Ralph to fly and they worked closely together for the next several years. In 1929, Ben Eielson, a pilot who had gained fame when he flew Sir Hubert Wilkins across the Arctic from Point Barrow to Spitsbergen, Norway, offered to buy Wien Alaska Airways. He represented a company that planned to create an air transportation system throughout Alaska. My father saw a chance to explore other opportunities so he accepted the offer and he and my mother headed for Minnesota for my birth. En route to Minnesota, they heard that my father’s dear friend and fellow Alaskan pilot Russell Merrill, for whom I am named, had disappeared flying out of Anchorage. Not long after that, Ben Eielson died when his plane crashed on a flight to Siberia. This was in the same Hamilton airplane that my dad flew on a similar mission earlier in the spring to retrieve furs from a different icebound vessel. Then an even bigger blow: While in Minnesota, they received word that his brother Ralph had died in a crash of an experimental diesel-powered Bellanca in Kotzebue.

When we returned to Fairbanks, my father’s younger brother, Sig, came with us. Sig and my dad flew home in my dad’s new Stinson while my mother and I took the train to Seattle, the Alaska Steamship to Seward, and then the train to Fairbanks.

My uncle Sig learned to fly in Alaska. He built up his time for his commercial license in a Buhl “Bull” Pup, which was powered by a three-cylinder Szekely engine of 45 hp. He became known for his pioneering flights in the Alaskan Arctic and was revered by the Native people there for his dependability, work ethic, and the services he provided to them. He was responsible for convincing the nomadic Eskimos who followed the caribou herds for food on the North Slope to settle in Anaktuvuk Pass so he could better serve them and keep them supplied. Some Native babies were even named Sigwien, as the people there had always treated his name as one word.

During the 1930s my dad worked to build his new company, Wien Alaska Airlines. By 1936, he had three other pilots and five airplanes: a Bellanca CH300, a 1933 Stinson, a 5AT Ford Tri-Motor, a Fokker Universal, and a Cessna C-34 Airmaster. By that time there was a lot of competition and it had become a cutthroat business to be in. It also was very hard to keep pilots. As soon as they gained experience, they would quit and start their own airline, creating more competition. In the late 1930s Wien Alaska Airlines lost five pilots in crashes. Those were tough times, yet my parents persevered.

In the early 1940s, my mother became very ill. The hospital bills drained my parents’ resources so they sold the airline to my uncle Sig to help pay expenses. All the airplanes were paid for and in good shape and my parents were proud of what they had been able to accomplish through sacrifice and hard work. Eventually my mother recovered but my dad grew less and less involved with the airline over time. He continued as a pilot for a time and was on the board of directors until he passed away in 1977, but he was no longer involved in the day-to-day management. After Sig took over, the management philosophy changed. Sig spent most of his time flying in the northern part of Alaska; however, the airline continued to grow because my father was loved throughout Alaska and the airline remained associated with his good reputation. Even though my parents sold it, the airline that my father started was destined to be a big part of my life.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, the phone rang. I could tell that it was something serious by the look on my dad’s face. Pearl Harbor had been bombed by the Japanese. No one knew what the future would bring. The only news that we received came from the delayed newsreels at the local theater and limited news from the local newspaper, the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.

In June 1942, the Japanese invaded the Aleutian Islands. I couldn’t help but remember the comment that was made by that bystander during the Japanese visit in 1937 with the Mitsubishi G3M bomber. Alaska was totally unprepared to defend itself. No one knew how far inland the Japanese would advance. All houses were required to black out all windows and no lights could be seen at night. Blackout wardens patrolled the streets. We anticipated air raids at any time.

There was a tremendous patriotic spirit. Schoolchildren brought their allowances and paper route earnings to school to buy savings bond stamps, 25 cents per stamp, and when a book of stamps was filled, for a total of $17.50, $25.00 could be claimed when the war was over. We drew war bond posters at school and they ended up in the windows of local stores. Collection drives began for aluminum, steel, copper, and rubber tires. Soon military airplanes were coming and going at Ladd Air Force Base on their way to Russia, as part of the Lend-Lease program, to fight on the eastern front against Germany.

I saw the planes coming and going at Ladd Field and I recognized each type from all the pictures and models I collected. I saw Bell P-39s and P-63s, North American B-25s, and Douglas C-47s and A-20s, along with others. I caught glimpses of Russian pilots in downtown Fairbanks. As part of an aviation family, and surrounded by all this activity, all I knew was that I just wanted to be a pilot.