Читать книгу Noel Merrill Wien - Noel Merrill Wien - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Young Pilot

Although I was getting closer to my dream of flying, my teen years were a period in my life when time seemed to stand still. Eventually I was able to work at Wien, cleaning the bellies of airplanes, gassing airplanes, changing oil, and doing whatever nontechnical jobs that needed to be done. In time, one of the mechanics, C. K. Harvey, taught me how to set the valve clearances, like those on a Pratt & Whitney Hornet engine on the Fairchild Pilgrim. By the time I was about fifteen, I was allowed to sit in the airplanes that had newly overhauled engines to run them at different power settings for the eight hour break-in period. It was the closest thing to actually flying at the time and I loved it. I graduated to being able to taxi the airplanes to the gas pit for refueling.

I was soon joined on the flight line by Douglas Millard. Doug started working for Wien Airlines in Nome under the supervision of my uncle Sig and when his mother moved to Fairbanks for a teaching job, he transferred to a flight line job there. We became good friends and as time went on, he was like a brother to Richard and me. We competed for the easy and fun jobs, such as taking garbage to the dump, breaking in overhauled engines, and taxiing airplanes to the gas pit, to avoid the jobs we didn’t like, such as cleaning the oil off the bellies of airplanes. Doug eventually went on to a flying career, retiring as a Boeing captain for Wien Air Alaska.

My big opportunity came when Bob Sholton, one of the Wien pilots, took an interest in me. Bob flew the Wien Stinson AT-19 and sometimes he would say to me, “Jump in” when he was on his way to the Yukon River villages. The Stinson was a surplus single engine military version of the civilian Gull Wing Stinson SR Reliants and sometimes it was so full that I just lay on top of the mail sacks. On the return he would let me fly the airplane back to Fairbanks. I was sixteen years old by this time and had already soloed but this was an opportunity to fly the big stuff. The Gull Wing Stinsons were widely used in the Alaska bush at that time because the plane carried a good load and had very strong landing gear. I loved flying the Stinson. Those planes did have one problem, however; the flaps could be positioned only in the full up or full down position. It would have been nice to be able to use partial flaps for takeoff so as to attain additional lift with heavy loads without creating so much drag that climb airspeed could not be reached. I remember seeing pilots try to set the vacuum-actuated flaps to an intermediate position on takeoff by metering the vacuum valve but getting full flap instead. They were able to get off the ground but ended up in the trees off the end of the runway.

A year after my first flights with him, Bob Sholton bought his own AT-19 and let me fly it quite a bit. My dad also bought one, which he later turned over to Wien Airlines. Bob eventually left Wien Airlines and flew DC-3s for Alaska Airlines. In time he and a partner bought two surplus Fairchild C-82s and they started Northern Air Cargo, which grew to be a large cargo carrier throughout Alaska flying DC-6s. I think that my interest in flying was stimulated by my early exposure to all kinds of airplanes and to the pilots, like my father and Bob, who flew them. Just like my father, I loved to fly and so my career choice was clear.

IN 1944, MY PARENTS STARTED ALASKA AIRCRAFT SUPPLY, a parts supply business at Weeks Field in Fairbanks. The business was just beginning to prosper when they had a visit from Joe Crosson. Recently retired from managing Pacific Alaska Airways, a subsidiary of Pan American headquartered in Fairbanks, he was now living in Seattle. Joe had partnered with Charles Babb, whose main business was selling used aircraft at Grand Central Airport in Glendale, California. Their new company was Northwest Air Service, an aircraft maintenance and parts supply business based at Boeing Field in Seattle. Joe was a very well known early Alaska bush pilot with an impressive record of aviation firsts in Alaska and someone whom my father held in high regard. They were planning to expand to Alaska and Joe proposed a merger with my parents’ company. A deal was consummated and our family moved to Seattle.

The plan was for me to travel with Joe back to Seattle but transportation between Alaska and Seattle was somewhat limited in 1945. Joe’s good friend Colonel Pat Arnold, Commander of the Tenth Air Rescue, based in Anchorage, offered to pick us up in a North American B-25 and take us as far as Anchorage. Colonel Arnold really stuck his neck out on this one; it was strictly against regulations to transport civilians in military aircraft. Colonel Arnold landed at Weeks Field and offered to show us the inside of the B-25. He “neglected” to deplane us before he started the engines and took off for Elmendorf Air Force Base near Anchorage. Once airborne he said, “Oh, sorry about that. I didn’t know you were still onboard.” Then Colonel Arnold let me fly most of the way. Little did I know that in a few years I would be going through Air Force pilot training in B-25s. When we arrived in Anchorage and were departing the base, Colonel Arnold had a little trouble explaining to the MPs at the gate how we got on the base to begin with. I don’t remember the colonel’s explanation but I was impressed and it seemed to satisfy the guard.

In Anchorage, Joe made arrangements with Ray Peterson to catch a ride to Seattle. Ray was the owner of Peterson Airways, later to become Northern Consolidated Airlines after merging with Gillam Airways and Dodson Air Service. Ray had a Lockheed Electra (Amelia Earhart vintage) that he had sold to a customer in Mexico, and Oscar Underhill was ferrying it to Seattle on the way to Mexico. We made the trip in one day with stops at Whitehorse and Prince George. I was able to handle the controls part of the time but when I was riding in the back, I became very airsick and spent most of the time hunched over the portable toilet.

Once in Seattle, I stayed with the Crossons until my family arrived. My folks found a house in the Ballard neighborhood and I attended Ballard High School during my sophomore year. During the school year, I took my first official flying lessons at the old Smith Dairy airport in Kent. Soon after, the flying school moved to Boeing Field where my new instructor was Sherry Phelps, a cute twenty-something ex-WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots). I was not into girls yet, especially older women, so I had no trouble concentrating on my flying.

It was a requirement at that time to have a minimum of eight hours from a certified instructor before soloing. So when I had eight hours, ten minutes, I soloed. It was on my sixteenth birthday, a few days before I got my driver’s license. I will never forget the thrill of finally being able to fly alone and not have to worry about what the instructor was thinking. Knowing no one could hear me, I sang the Army Air Corps song at the top of my voice, maybe not as loud as I remember hearing Robert Crawford sing it at our house, but loud nonetheless. When I landed, I noticed my mother was a wreck. Apparently, she had nearly fainted when I lifted off on my first takeoff. I never understood why she was worried until I watched both my sons solo on their sixteenth birthdays.

MY DAD LEFT NORTHWEST AIR SERVICE THAT SUMMER and we all returned to Fairbanks. We bought a 1941 DeSoto and drove up the Alcan Highway, now called the Alaska Highway. It wasn’t really a highway then since so much of the road was a muddy trail with long stretches of “gumbo” mud, which clung like cement to the underside of the car when it dried. I think it took about two weeks to make the drive since we had to drive east from Seattle to Montana and then head north into Canada via Edmonton and Calgary. Years later, the Hart Highway opened up from Vancouver through the Fraser River Valley to Prince George, cutting off about a thousand miles.

After arriving back in Fairbanks, I was fortunate to be able to work for the airline again. I used the money to build up flying time toward my licenses while I finished high school and I attained my private pilot rating that summer.

Now that the war had ended, Cessna Aircraft was back in the business of building civilian airplanes and the Cessna 140 came on the market. Cessna asked my parents if they would accept the Alaska distributorship for the state. My mother was pressed into service and handled all the sales paperwork. It was a great opportunity for me because I was able to build some time in the brand-new 140s before they were sold. I needed every chance I could get to fly because my time was mostly consumed by working for the airline after school and on weekends. One winter day I thought I would get some flying in during my lunch hour in a demonstrator Cessna on skis that we had. However, before I could fly, the engine needed to be heated with a Herman Nelson heater. I heated the ice off the tail and hurriedly moved the heater to the engine, not realizing that the chimney from the heater was right under the wing. After setting the heater in place and putting the heat tube inside the engine, I looked around to find that the wing was on fire. Fortunately, the metal wing ribs and spar were not damaged but the outer third of the fabric was gone. I was devastated.

ONE DAY IN 1947, DURING MY JUNIOR YEAR, I was sitting in study hall gazing out the window, which I did most of the time. The final approach to Weeks Field passed by the school and suddenly I saw two Stinson L-5s go by. I knew that Sam White and Steve Miskoff were arriving in Fairbanks from the states with these newly acquired World War II–surplus aircraft. When the bell for the lunch hour rang, I tore out of school and ran all the way to the airport. While I was still breathing hard, Sam said to me, “Hey, Merrill, do you want to fly it?” I had received my private license on my seventeenth birthday and had recently checked out in Alaska Flying School’s L-5, but I don’t think Sam knew that I had flown an L-5 before. I jumped in and made two landings. When I landed, I thanked Sam and ran back to school just in time for the bell. That airplane represented Sam’s total worth at the time and he probably borrowed money to buy it. I will never forget his kindness.

Sam was an important person in my life and to this day he is a legend in Alaska. He grew up in Maine and worked on the steam-powered logging tractors that hauled the logs down off the high logging areas. It was a dangerous job but Sam became very good at driving the machines. He was a veteran of World War I, having served on the front lines in the infantry. After the war, he got a job with the Boundary Commission, clearing a border line between Alaska and Canada. Then he went to work for the Alaska Fish and Game Commission. He traveled all over Alaska with dog teams, horses, mules, and on foot, watching for violators of the fish and game laws. He arrested any violators, even friends. This was hard for him to do but for Sam the law was the law. After a few years traveling by dog teams he began to see airplanes fly overhead and the thought entered his mind that maybe there was a better way to get where he was going. He became friends with my father and my uncle Ralph.

Sam bought an airplane with his own money and my dad and Ralph taught him to fly, making him the first flying game warden in Alaska. Using his own airplane drastically cut into his earnings until he was finally able to convince the game commission to finance an airplane. As time went on, Sam was asked not to arrest certain high profile individuals and that did not sit well with him. He eventually left the commission and went to work as a pilot for Wien Airlines. Since Sam knew how to live year-round in the wilds of Alaska he was assigned to take US Geological Survey personnel all over the territory for mapping surveys and would be gone many weeks at a time.

Sam was a skilled and diligent pilot. A brief story, one of so many I know about Sam, illustrates this: Sometime during the early 1940s, I was in the kitchen when the phone rang. My dad answered and it was Leon Vincent at the KAZW aeronautical radio station. He said that Sam White had called in advising of an emergency situation. Sam was flying a Gull Wing Stinson through some turbulence when one of his skis became detached from the forward shock cord and the cable that held the ski in position. The front of the ski went down and the rear of the ski hung up on the bracket on the landing gear where the wheel pant normally is attached, holding the ski in the straight down position. This put the airplane into a spiral that Sam could not control. Then the other ski did the same thing. This allowed him to stop the spiral but he had to use full throttle and hold the control wheel all the way back in his stomach. He was descending but thought he could make it to Circle City. He barely managed to make it and flew at full throttle onto the snow-covered runway. The landing gear broke away and when he came to a stop, he was trapped in the pilot seat. He had onboard 110 gallons of case gas in five-gallon tin cans and some had broken open. Gas was dripping everywhere. He was pulled from the airplane by the local people and fortunately the airplane did not catch fire. Sam was diligent about tying down his loads and this probably saved his life. Sam and my dad constantly stressed the importance of tying down the cargo. Sam was in the hospital for quite a while but eventually made a full recovery.

During the latter part of Sam’s flying career, he was based at Hughes on the Koyukuk River. Around 1960, Sam asked me to bring his float-equipped L-5 to Hughes for the summer and then to bring it back to Fairbanks in the fall. I did this several times but once when I was getting the plane ready to depart from Fairbanks, I made a big mistake. My friend Doug Millard and I were putting the battery in the airplane on the floor under the instrument panel. The fuel line from the overhead fuselage tank passed by just above the battery. I mistakenly hooked up the negative terminal first and then when I attached the positive lead to the battery, the handles of the water pump pliers clipped the fuel line and caused a flaming stream of gas to pour into the fabric-covered belly. I tried to stop the stream of gas but every time I did it I burned my hand. Doug was pouring buckets of water in the belly but the flaming gas continued to float on top of the water. Finally, a Wien mechanic saw our predicament, grabbed a towel from his pickup, dunked it in the water, and told us to wrap it around the gas line. That stopped the source and we were able to put out the fire. Miraculously, the only damage was a small hole in the belly fabric and a ruined cylinder head gauge under the panel. We easily patched the hole and replaced the gauge with one that I happened to have. When I arrived at Hughes and Sam saw the bandages on my hands covering my burns, he said, “You should have let it burn.” He was upset about my burns, not about his plane. That captures perfectly who Sam White was. When Sam sold the L-5 years later, the new owner burned up the airplane, like I almost did, the same way.

That fall, when I brought Sam’s airplane back to Fairbanks, I had another adventure. As always during the preflight at Hughes, I religiously drained the gas tanks and the fuel strainer to remove the water that often leaked though the gas caps when it rained. I got some water out of both tanks and the strainer and I thought I was all set. On the way to Fairbanks the gas was getting low in the right tank and I thought that it might be a good idea to switch tanks before it was completely empty. Shortly after switching tanks, the engine quit. That was a big surprise. I knew there was still fuel in the first tank but didn’t immediately switch back to it. Instead I wasted time trying to get the full tank to feed. Finally, I switched back to the low-fuel tank expecting it to come to life. It did not. I tried everything to get it to start. There was no time to even be scared. My only thought was, Another fine fix I’ve got myself into. I looked for a place to land and the only spot was in the Melozitna River, which was more like a creek than a river. I figured I could touch down in the water and slide up on a gravel bar. As I was setting up for the approach, the engine started to bark but it would run only at idle then would quit when I advanced the throttle. I figured out that I could gradually increase the throttle settings before it would quit and it became apparent that eventually I could get full power back. The question was, would it happen before I ran out of airspace? I had to decide whether to keep messing with the throttle or commit to the river. Having recovered some power caused me to overshoot the river but I got the engine to come back to life just over the trees.

The next year, Sam brought the airplane back from Hughes himself but he did not switch tanks until the tank ran out. By that time he was over the Yukon River and he was able to dead stick it into the river. After that we figured out that even though we were draining all the tanks and the fuel strainer, we were not switching to the other wing tank and draining that line between tank and engine. Another lesson learned.

Sam White was like a second father to me and Richard. In the way he displayed a very high standard of conduct and integrity, he reinforced the guidance we received from our dad and became another important role model for us. When my son Kurt was born, my wife and I asked Sam if he would be Kurt’s godfather. He was glad to do it and took his role very seriously.

WE SOLD QUITE A FEW CESSNA 140S BUT when the sales started to decline, my parents turned the distributorship over to Uncle Sig and he formed a new company called Alaska Aeronautical Industries.

In the spring of 1948 my parents decided to move back to Seattle. We drove the same 1941 DeSoto back down the Alaska Highway accompanied by our good friends Doug Millard and his mother, Clara Millard, who were on their way to Iowa. The gumbo mud was as bad as ever and on some stretches we had to be towed through it by D-8 Caterpillars that were stationed along the highway.

The first time we encountered a bad gumbo mud area, the D-8 Caterpillar was idling along the side of the road but the drivers had gone to lunch. Doug, who had just turned sixteen, jumped out of their 1942 Ford and ran over to the tractor. His mother gasped, “Douglas, what do you think you are doing?” He jumped up into the cab and the next thing we saw was a big puff of black smoke blow out of the exhaust. The D-8 spun around and headed for our cars. After we helped him hitch up the cars, he towed them through the mud. When the drivers returned from lunch they were amazed to see a kid doing the driving. We thought that we would be in a lot of trouble but the only thing the driver said was, “Are you making any money?” More cars had gathered behind by then so the drivers took over the duty.

My parents bought a house in the Seattle suburb of Lake Forest Park and I enrolled at the University of Washington to start classes in the fall in aeronautical engineering. I got a job for the summer as gas boy at the nearby Kenmore Air Harbor, a flying service and flight school at the north end of Lake Washington. Most of my pay went to working toward my float rating and commercial license.

My main flight instructor there was Bill Fisk. He was a World War II–B-24 pilot and Kenmore Air’s main pilot and instructor for many years. I learned much from Bill. He taught me how to loop and barrel roll the Taylorcraft on floats, along with night takeoffs and landings in that plane. I learned that when the altimeter gets close to what it was reading when the plane was on the water, I should set up a 200- to 300-feet-per-minute rate of descent at an airspeed that sets the touchdown attitude for landing. This is the same procedure that is used for landing on glassy water. That training served me well in later years during my many glassy water landings in Alaska.

When anyone got their float rating it was customary to throw them into the lake. When I got mine, four Kenmore employees dragged me toward the water. I acted limp and lifeless until we got to the T in the dock when I suddenly straightened out, causing the two guys holding my feet to go flying into the lake. I was then able to drag one of the two holding my arms into the lake with me, which was probably not the most sportsmanlike thing to do. Tom Wardly and Ted Huntley, two of the guys who went into the water with me, went on to have very distinguished flying careers.

In June 1949 I traveled from Seattle to Wichita, Kansas, with Uncle Sig to pick up two new planes for Wien Airlines. I flew a new Cessna 140A back to Alaska and Uncle Sig flew a Cessna 170. Shortly after arriving in Fairbanks with the new Cessna 140 and returning to my usual summer job at Wien, one of our operations people came to me when I was sweeping floors and said that I had a charter flight. Whaaaaaaat? I thought. I am going to fly a charter? I had not been hired as a pilot and didn’t yet have my commercial license.

I did not know my passenger but we took off and I flew around Fairbanks showing him the sights. When we landed, I found out that he was Jerry Merrill, the brother of Russell Merrill, my father’s good friend who had disappeared in 1929. The airport in Anchorage was named Merrill Field after him. Sometimes I am asked what the relationship is between me and Merrill Field. I would like to say that it was named after me but I don’t think that would fly. Every year after our flight, Jerry Merrill sent me a telegram wishing me happy birthday. When he died he willed me $500.

While the rest of the family remained in Seattle, I spent the summer with Sig in Fairbanks working odd jobs for Wien Airlines and getting as much flying time as possible. In July, I passed my commercial check ride with Hawley Evans, founder of Fairbanks Air Service, and a highly respected Alaska pilot.

About the time that I was going to go back home to Seattle to start another year at the University of Washington, I received an offer to fly a North American Navion to Sun Valley, Idaho. Apparently the airplane had been flown up to Alaska by a pilot who thought the route was too sparse and treacherous so he left it with Bob Rice in hopes that he could find someone to fly it back to Sun Valley for him. Bob, who had previously flown for Wien Airlines as chief pilot and had since left to start his own charter service, had two Navions of his own that he was using for charter work so he checked me out in his. My high school friend George Morton flew to Seattle with me and then I delivered the plane to Sun Valley.

That winter, I aborted my college year after completing the first quarter in 1949 to get to work on my instrument rating with Harry Cramer on a Link Trainer he kept in the terminal building at Boeing Field. After I completed my required twenty hours of Link, Harry talked me into working on my Link instructors rating. As part of my training I operated the Link under Harry’s supervision, teaching primary instrument students and operating the Link for Boeing pilots and nonscheduled pilots flying to and from Alaska. In March of 1950 I earned my instrument rating, followed a month later by my Link instructors rating. Every time I qualified for a new rating, it was a great feeling, a sense of another stepping stone completed. Then I would focus on the next one.

THE DAY AFTER I PASSED MY INSTRUMENT FLIGHT check, my dad and I flew to Wichita to pick up a brand-new 1949 Cessna 170A that the family had purchased for personal use. While there, we visited the Mooney factory. The Mooney Mite single seat airplane had recently been introduced and they were very anxious for my dad to fly it. He told them he would take a pass but that his son would like to fly it. They didn’t seem to be very enthusiastic about that idea but they reluctantly gave me a cockpit check and turned me loose. I flew it for about thirty minutes and thoroughly enjoyed the experience. Even though it only had 65 hp, it felt like a little fighter. On landing, it didn’t touch the ground when I thought it would and as it continued to settle lower, the thought came to me that maybe I forgot to lower the landing gear. When it did touch down it felt like my butt was sliding on the grass. Two days later we flew to Seattle and a few days after that we left for Fairbanks.

Shortly after arriving in Fairbanks with my dad and the new Cessna 170, I returned to my usual summer job at Wien. My mother, brother, and sister drove a new Ford back up the highway as our family returned to Fairbanks to live.

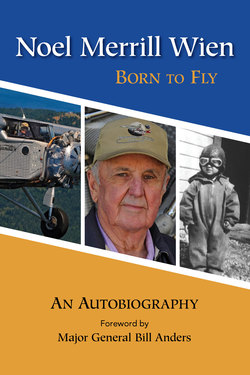

My father, Noel Wien, created history in 1925 by making the first flight north of the Arctic Circle anywhere in the world. He is seen here hand cranking the Standard J-1 at Wiseman, Alaska, for the return trip to Fairbanks.

Famous early Alaska pilot Joe Crosson looking at me in the sled when I was a baby.

This was taken in 1927 in Nome, Alaska, when my dad started Wien Alaska Airways. Note the spare prop tied to the side of the fuselage.

Here I am getting some pretend flying time in the Bull Pup.

In 1938, Howard Hughes stops in Fairbanks flying a Lockheed Model 14 on a record-breaking around the world flight of just under four days. P341-Cann-7, Alaska State Library, Photographers in Alaska Photo Collection.

Photo of the Japanese Mitsubishi G3M visit to Fairbanks in 1937, supposedly on a goodwill tour of Alaska.

Wiley Post lands in Fairbanks in 1933 on his around-the-world record flight of just under eight days.

This is the Avro Avian airplane that ended up in our backyard for us kids to play in, and eventually demolish. It originally belonged to Robert Crawford, composer of the Army Air Corp song who also grew up in Alaska.

Hap Arnold arrived in Alaska with ten Martin B-10s in 1934 to prove the capabilities of the Army Air Service. Arnold later became commanding general of the US Army Air Forces during World War II.

When I was five years old, in 1935, we greeted Wiley Post and Will Rogers arriving on the Chena River near Fairbanks. They were on their way to Point Barrow and points west. They were killed near Point Barrow a few days later. Wiley is getting out of the cockpit and Will Rogers is standing on the right wing. Joe Crosson, famous Alaska aviator, and mechanic, Warren Tillman, are on the dock.

Solo day, April 4, 1946, Boeing Field, with my instructor, Sherry Phelps.

My dad, Noel Wien, and Bob Sholton, 1949, Fairbanks, by the tail of the Wien Fairchild Pilgrim. Bob took me with him on several mail runs in the Stinson AT-19.

One of my first bush flights in the spring of 1950 at the village of Beaver on the Yukon River ice.

The crew I first flew with most frequently the summer of 1950. I’m on the left with Captain Fred Goodwin standing between Wien Airlines’ first stewardesses, Betty Windler and Patsy Hornbeck.

I was hired by Pan American in the summer of 1951, and this photo was taken at Juneau, Alaska.