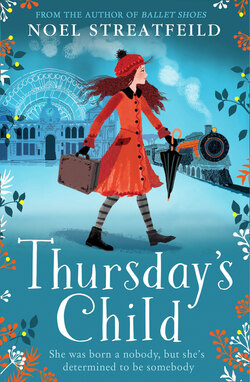

Читать книгу Thursday’s Child - Noel Streatfeild - Страница 8

Chapter Two PACKING UP

ОглавлениеThe orphanage – called St Luke’s – was, so pamphlets pleading for funds said, ‘A home for one hundred boys and girls of Christian background’. The building had been given and endowed by a wealthy businessman who had died in 1802. He had stipulated in his will that though the actual building was near Wolverhampton no child from any part of the country who was an orphan and a Christian was to be refused a vacancy provided they were recommended by a clergyman of the Established Church.

‘So splendid of the archdeacon to recommend you,’ the rector said to Margaret, ‘for he carries more weight than I could hope to do, and then, of course, there is his brother who is a governor.’

One of the worries of the committee who ran St Luke’s was how to collect their children. Most of them were too young to travel alone, especially if the journey included changing trains and crossing London. So a system had been devised by which new arrivals were collected in groups. When possible, new entrants were delivered to London by their relatives or sponsors, and there they were met by someone from the orphanage.

The rector came up to Saltmarsh House each time there was news about Margaret, but it was March before he arrived with definite information. Hannah always considered it unseemly that the rector should come into the kitchen, so he was led into the drawing room, which was cold, for neither Miss Sylvia nor Miss Selina came down until teatime so the fire was never lit until after luncheon.

‘Stay and hear the news,’ the rector told Hannah, ‘for it concerns you.’ He opened a letter from the archdeacon and read.

I have now heard from the chairman of the committee of good ladies who run the domestic affairs of the orphanage. She says there are two members of one family to be admitted at the same time as your protégée Margaret Thursday. They are to meet in the third class waiting room at Paddington Station on the 27th of this month at 1 p.m. The train does not leave until 2.10, but the children will be given some sort of meal. They say Margaret Thursday should bring no baggage as all will be provided.

Hannah was appalled.

‘No baggage indeed! That’s a nice way for a young lady to travel. Margaret came to us with three of everything and she is leaving us the same way, not to mention something extra I’ve made for Sundays.’

‘I think,’ the rector explained, ‘the orphans wear some kind of uniform.’

‘So they said on that first form they sent,’ Hannah agreed, ‘but there was no mention of underneath.’ Then she blushed. ‘You will forgive me mentioning such things, sir.’

The rector dropped the subject of underneath.

Do you think arrangements could be made for someone to stay with your ladies for one day while you take Margaret to Paddington Station? I would take her myself, but the archdeacon says …’ He broke off, embarrassed. Hannah understood.

‘No, better I should go. It’s not a gentleman’s job. We’ll have to book on the carrier’s cart to the railway junction for London.’

The rector was glad to do something.

‘I shall see to that, indeed, I will arrange everything. All you have to do is to be ready by the 27th. Can you manage that, Margaret, my pet?’

Margaret had been waiting for a chance to speak.

‘Can I take my baby clothes with me?’

‘Whatever for?’ gasped Hannah.

‘I don’t quite see …’ the rector started to say, but Margaret interrupted him.

‘I don’t want to get to this St Luke’s looking like a charity child. If I show my baby clothes – three of everything and of the very best quality – they’ll know I’m somebody.’

The rector looked at Margaret’s flashing eyes. He spoke firmly for he wanted her to remember his words.

‘If you behave like somebody you will be treated like somebody. Never allow anyone to suggest that because you do not know who your parents were you are in any way inferior to others more fortunately placed.’

‘You needn’t worry,’ said Margaret. ‘I never will. But what I think is that it will help if everybody can see I’m someone who has a mother who cared that her baby was properly dressed. How can people know that if they don’t see the clothes?’

The rector held out a hand to Margaret and she came to him.

‘It is my hope that some day your mother will come and claim you. You do not know and I do not know what terrible thing happened to her that forced her to leave her baby on the church steps. Nor do we know what new misfortune has deprived her of money, but I believe – and I pray for this night and morning – that one day her fortunes will change and then she will come to me and say: “Where is my Margaret?” Then I shall ask: “First, madam, describe the baby clothes you left for the child, otherwise how do I know you are her mother?”’

‘Well, truthfully,’ said Margaret, ‘it’s not likely the wrong mother would want me. What for?’

The rector smiled.

‘How do we know?’ he teased her. ‘Some day you may prove to be the heir to a great fortune. Remember Thursday’s child has far to go.’

‘Or,’ Hannah suggested, ‘you might become famous. I’m always telling her, sir, she might write a book. You ought to hear the stories she tells me of an evening, and all out of her head.’

‘So you see,’ said the rector, ‘I must keep the baby clothes for the day when your mother claims you.’ He got up. ‘Now I must get on with your affairs. I will arrange for the carrier to call here on the 27th.’

Hannah still had the wicker basket which she had brought to Saltmarsh House. Now she gave it to Margaret. To make her an ‘underneath’ trousseau she had raided the old ladies’ cupboards. There she had discovered an unused length of flannel, part of a roll bought to sew Miss Selina into one winter when she had pleurisy, and there was a voluminous cambric petticoat once worn by Miss Sylvia and other useful bits and pieces. She had sewn the clothes at night after Margaret was in bed, so it was the night before she left that Margaret saw them for the first time after they were packed in the wicker basket.

‘Three of everything,’ Hannah said proudly, lifting layers of tissue paper. ‘Three plain cambric petticoats. Three pairs of drawers with feather stitching. Three scalloped flannel petticoats. Three linings in case at that orphanage they make you wear dark knickers. Three liberty bodices and three nightdresses – all fine tucked.’ Then Hannah drew back yet one more piece of tissue paper. ‘And here for Sundays is a petticoat and a pair of drawers edged with lace.’

Margaret gasped. Then she threw her arms round Hannah.

‘Lace! Oh, darling Hannah, thank you. It’s like being a princess. When we go to church on Sundays I’ll be sure to see my frock sticks on my heel so everyone can see the lace.’

Hannah was shocked.

‘You’ll do nothing of the sort. What you have to remember is you were spoke for by an archdeacon so don’t shame him.’ Then she turned back to the wicker basket. ‘Your Bible and Prayer Book are in the bottom. I’ve tucked your stockings in wherever there is room, but on the top are your hankies, your brush and comb, your toothbrush and one nightie so you can get at them easy if you arrive late. And in a corner down at the bottom is that tin of mine with the cat on it you’re fond of. I’ve filled it with toffees.’

Suddenly it all seemed terribly final. Although most of Margaret had accepted that she was going to the orphanage, another part of her had refused to believe it. Could she really be going away from the rector and Hannah and all the people she knew and loved? With a howl she threw herself at Hannah.

‘Must I go? I’ll work in the house much more than I ever have before. I’ll like dusting, truly I will, and I’ll hardly eat anything at all.’

Hannah, her eyes dimmed by tears, gave Margaret a little push.

‘Don’t, my darling. Don’t. It won’t do no good.’ Then she knelt down and closed the wicker basket and fastened round it a leather strap.