Читать книгу Tenryu-ji - Norris Brock Johnson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

DEATH, DREAM, AND THE GENESIS OF A TEMPLE

The Temple of the Heavenly Dragon was not parented by aesthetic and religious sensibilities, exclusively. Generations of brutal conflict flowed across the mountains and plains west of the City of Purple Hills and Crystal Streams. Fear and violence, betrayal and atonement, and compassion, also were constituent aspects of the birth of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon and the life of the pond garden.

Nearly half a century had passed since the Saga emperorship. Four people of influence subsequently appeared who will directly influence the birth of Tenryū-ji: Emperor Go-Daigo (1288–1339); the brothers Tadayoshi (1306–52) and Takauji (1305–58) of the Ashikaga, a branch of the Minamoto clan of families; and the venerable priest Musō Soseki (1275–1351). Along with religious belief and aesthetic sensibilities, we will discover sharp shards of suffering strewn about our archaeology of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon.

Emperor and Shōgun

Emperors continued to claim authority for the divine right to rule imperially, through societal belief in the descent of emperors from the Shintō deity Amaterasu-o-mi-Kami. Yet, imperial rule increasingly was challenged by aristocratic families and by the appointed administrators (regents) of lands, provinces, outlying Kyōto.

Revolts in the provinces against imperial authority were frequent. As a repercussion of a decisive revolt in 1185, in 1192 Yoritomo of the Minamoto clan of families declared himself Seii Taishōgun (“Barbarian-Subduing General”). Yoritomo established the seat of his military regime (bakufu) in Kamakura, thereby challenging the authority of the court of emperors in Kyōto. With the death of Yoritomo in 1199, clans of aristocratic families, the Hōjō especially, and subsequent shōgun, continued to challenge the rule of emperors for the next several centuries.

In April of 1318, Crown Prince Takaharu ascended to the throne in Kyōto as Emperor Go-Daigo. In 1326, Hōjō in Kamakura “requested” that Go-Daigo assume the position of Titular Emperor, an impotent position without influence, so that an emperor of Hōjō choosing could be installed on the throne in Kyōto. Go-Daigo wanted to restore the power of emperors, weakened over the last several hundred years. Go-Daigo rebuffed the direct challenge to imperial rule and right of succession and began a series of attacks on Kamakura.

In 1331, Takatoki of the Hōjō sent thousands of soldiers to Kyōto in response to Go-Daigo’s continuing attacks on Kamakura. Informed of the forces riding against him, Go-Daigo and many of his loyalists fled Kyōto and retreated southward to a monastery on Mount Kasagi. Soldiers from Kamakura pursued Go-Daigo and, though met with force by warrior-monks loyal to Go-Daigo, the monastery on Mount Kasagi was seized then razed. Go-Daigo managed to escape but was captured in 1332 and exiled to the island of Chiburi (present-day island of Oki). The military regime in Kamakura then installed young Prince Kazuhito (Emperor Kōgon, 1313–64) to the imperial throne in Kyōto.

In 1333, Go-Daigo escaped from the island of Chiburi as loyalists began military campaigns to restore the emperor’s rule in Kyōto. Prince Daito [Morinaga, the eldest son of Go-Daigo], his son Akamatsu Norimura, Nitta Yoshisada, and Takauji of the Ashikaga led large armies in attacks around Kyōto and in Kamakura on forces loyal to the Hōjō and the military regime, such that “by afternoon the sky was full of smoke … there was no daylight [in Kamakura]. It was as if the scene had been rubbed over with ink.”1 Returning to Kyōto as emperor, Go-Daigo initiated the Kenmu Restoration and Era [Kenmu no Shinsei, 1333–36], a short-lived period meant to solidify imperial rule.

The power of the emperor, though, remained weakened. Go-Daigo had to depend on military men, such as Takauji and Tadayoshi, for control of lands under imperial rule.

Takauji of the Ashikaga initially had provided military support for the Hōjō, to which his family was related by marriage. Takauji led one of the wealthiest and most influential families in the provinces east of Kyōto. Hōjō regents named him a constable, placed a sizeable military force at his command, and ordered him to march against Go-Daigo, then in Kyōto. Takauji, though, sensed the eventual demise of the Hōjō and subsequently changed allegiance. He placed his army at the disposal of loyalists campaigning for restoration of imperial rule under Go-Daigo.

Go-Daigo then dispatched Takauji to quell a rebellion in Kamakura. Takauji followed the orders of the emperor and marched to Kamakura where he quelled the forces of rebellion against imperial rule. Soldiers such as Takauji, though, expected spoils of war rather than leadership of ceaseless military campaigns as reward for supporting emperors. Takauji desired control of provincial lands to the east of Kyōto. He coveted the title of shōgun. Takauji initially had asked Go-Daigo to appoint him shōgun, but Go-Daigo denied his request, as he did not want to encourage potential challenges to the authority of emperors.

In 1335–36, Takauji seized control of Kamakura, routed the last of the Hōjō regents and the bakufu and had himself appointed shōgun. He then began to distribute land to his officers, undermining Go-Daigo’s authority to command imperial lands and soldiers. Go-Daigo branded him a traitor and sent punitive expeditions to Kamakura to rout Takauji and his army.

At roughly the same time, Nitta Yoshisada also turned against Go-Daigo when he was sent by the emperor to dispatch Takauji from Kamakura. Yoshisada subsequently joined forces with Takauji and their combined forces moved on Go-Daigo in Kyōto, defeated imperial troops, and marched into the city “leaving flames behind them as they destroyed the palace and the mansions of Court nobles and generals, notably those of their enemies.”2 For a second time, Go-Daigo was forced into exile; this time, the emperor fled into the mountains of Yoshino south of Kyōto. Mountainous and difficult to access, “the wild country of Yoshino was like a natural fortress.”3 In early 1336, Kitabatake Akiie, a loyalist to Go-Daigo, forced the troops of Takauji and Yoshisada from Kyōto, and Go-Daigo briefly returned to the city. In response, in late 1336 Takauji again forced Go-Daigo from Kyōto and installed Prince Yutahito (Kōmyō, 1322–80, a brother to Emperor Kōgon) as emperor.

Two emperors thus simultaneously claimed the right to rule: Go-Daigo organized an administrative court (Nanchō, the Southern Court) while in exile in Yoshino; the child-emperor Kōmyō, a puppet of Takauji, held court (Hokuchō, the Northern Court) in Kyōto. Most historians privilege the stronger position of Go-Daigo, as he managed to keep possession of the imperial regalia—the seal of the emperor and perhaps a mythic sword (Kusa-Nagi, “Grass Mower”), one of the Three Treasures of Shintō.4 Armies of the Northern Court supported Kōmyō and, under the leadership of Takauji, fought armies of the Southern Court, who supported the restoration of Go-Daigo to the throne in Kyōto.

Forests of Suffering

Violence and bloodshed seeped and settled into the land on which the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon will rest. Amid suffering, though, there appeared the influential presence of the venerable Rinzai Zen Buddhist priest Musō Soseki (fig. 36).

Soseki remains indelibly linked to the present-day Temple of the Heavenly Dragon, especially so for priests within the temple, as we will see.5 Soseki was born on November 1, 1275, to an influential family in the province of Ise (present-day Mie Prefecture). His father belonged to the influential House of Genji (Minamoto, descended from the prominent clan of families in the Tale of the Genji), and his mother, who died when he was about three years old, belonged to the influential House of Heike, by kinship related to the Taira. When Soseki was nine years old, his father presented him to the venerable priest Kūa Daitoku at the Buddhist temple of Heian-ji.

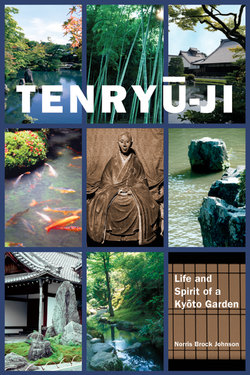

FIGURE 36. Musō Soseki (Kokushi).

Soseki initially studied Shingon and Tendai practices of esoteric Buddhism (密教, Mikkyō). Esoteric meant hidden and secreted, as Mikkyō was intended only for an initiated elite.6

The Shingon studied by Soseki at the time conceived of existence as a manifestation of the Supreme Cosmic Buddha, with less emphasis on the historical Buddha. Though esoteric, “we can discern, when free from illusion, the body and life of the Great Illuminator even in a grain of dust or in a drop of water, or in a slight stir of our consciousness.”7 Shingon is attributed to Kūkai (Kōbō Daishi, 774–835). Nature was the nature of the Cosmic Buddha. Kūkai loved mountains, in particular, and he lived much of his life within forests and on mountains. The Ise area within which Soseki was born still is associated with venerated mountain shrines (such as Ise-jingū), natural features venerated as kami (such as Meoto Iwa, the “Wedded Rocks” near the village of Futami), and with the mountain yamabushi, practitioners of Shugendō. Soseki was deeply and persistently attracted to the love of nature he found associated with practitioners of Shingon, such as Kūkai.

Soseki’s studies of Shingon were successful. At the age of seventeen Soseki was given the monk name Chikaku (“Clear Knowledge”). In 1292 his head was shaved and he was ordained a Shingon priest at Tōdai-ji in present-day Nara Prefecture. Here, Soseki studied intensively with the venerated Gyōren (Jikan Rishi). A formative phase in his life began when he witnessed the prolonged death of Gyōren. The beloved teacher appeared to suffer greatly as he died. Esoteric rituals did not ease the priest’s death. Nothing Gyōren had been studying so intently all of his life demonstrated efficacy in negating suffering. “He [Gyōren]” Soseki wrote, “studied the sūtras diligently but not one word could help him at his death.”8 In despair over suffering, as well as witnessing that apparently nothing could negate suffering, Soseki ceased his studies of Tendai and began a hundred-day solitary meditative retreat—“effectively ‘sitting under a tree’ again, his mind roaming in the landscapes that had comforted and calmed him when he felt confused or overwhelmed by the suffering in the world around him.”9 For Soseki, mindful experience of nature provided him with some respite from suffering. Mindful experiences of nature will be a predominant intent of the temple landscapes, compassionate aids to calming the mind and heart, with which Soseki later will be involved.

It was during the later phase of his retreat that, from deep within his meditative experience, Soseki became aware of the thought that led him to the name by which he still is venerated. His Way for some time will be trekking, alone mostly, within nature. Nature will continue to be a mirror for deep, calming, meditative experiences of his own nature—thus “mu [夢], dream, and sō [窓[, window.”10 Musō. This name says that Soseki conceived of himself as the vehicle seeing into and potentially negating his own suffering and perhaps the suffering of others.

Musō (as we now will refer to him) went on to study Tendai, a school of Buddhism traced to Saichō (Dengyō Daishi, 767–822). Tendai sought to free Buddhism from the dogmatism of esoteric ritual Musō experienced within Shingon. The Tendai to which he was exposed accommodated study of the venerated words attributed to Shākyamuni.

Musō’s early life experiences at this point in several respects recapitulate early life experiences of Siddhārtha Gautama. Musō’s early confrontations with death and his despair over suffering, for instance, mirror the confrontation with death and despair over suffering early experienced by Shākyamuni.

Siddhārtha was the son of Shuddhodana [Pure Rice King], ruler of the influential Gautama lineage of the Shākya clan of families. The Shākya were high-caste (Kshatriya) twice-born rulers over hundreds of thousands of people in Kapilavastu in the southern foothills of the Himalaya Mountains, the fertile delta area of the river Ganges in the present-day Terai region of Nepal. It is believed that Siddhārtha’s preordained destiny was to confront suffering directly, and Buddhism fruited from Siddhārtha’s compassionate response to the suffering he witnessed beyond the privilege within the gates of his father’s palace. There are variant narrative descriptions of a signal incident where Siddhārtha, one day riding with Channa, his charioteer, initially bore witness to suffering, first clothed as an old man riddled with decay. The old man, though, was a deity compassionately taking on this form so as to stimulate Siddhārtha’s “awakening.” As they rode in his chariot, Siddhārtha then spied another old man covered with boils. He then witnessed a body being carried by untouchables to the cremation grounds. Finally, Siddhārtha spied a beggar, a wandering priest, who while outwardly poor appeared powerfully calm of mind. Siddhārtha is reputed to have said that “although brought up in wealth, I was by nature very sensitive, and it caused me to wonder why, when all men are destined to suffer old age, sickness, and death, and none can escape these things, they yet look upon old age, sickness, and the death of other men with fear, loathing, and scorn. This is not right, I thought.”11 Siddhārtha subsequently renounced th privileges of the Shākya, left his family, and began to wander amid forests and mountains. Siddhārtha’s renunciation of inherited privilege, and his subsequent compassionate response to suffering, became especially important to Musō.

Musō Soseki and Siddhārtha Gautama both were born into families of relatively high social status. Around 563 B.C., Queen Māyā gave birth to Siddhārtha within the still--celebrated gardens of Lumbini. She died several days later. Both Musō and Siddhārtha early in life experienced the death of their mothers. Siddhārtha “was reared in delightful palaces from whose parks every sign of death, disease and misery was removed.”12 Both Musō and Siddhārtha were attracted to what we would term a religious life in association with similar reactions to death and to the apparent persistent existence of suffering in the world. Finally, gardens were an intimate aspect of the life of Siddhārtha Gautama, who was born in a garden, and of Musō. Musō came to see gardens as a compassionate means to stimulate states of awareness and behavior termed “enlightenment,” and he later will influence the design of the pond garden aspect of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon.

THE BONES OF EMPTINESS

Musō felt that the textual study of esoteric Buddhism, both Shingon and Tendai, did not affect suffering in the world. Musō was led to the Zen school of Buddhism through his conclusion that the truth of suffering could not be experienced through formal study of sūtra or the practice of esoteric ritual.

The pedagogy of Zen Buddhism emphasizes the direct face-to-face relationship of teacher and student, as with Empress Danrin and Gikū Zenshi. Musō thus began his study of the Zen school of Buddhism by seeking an enlightened teacher and a sangha in which to study. Musō had thought to study with the venerable priest Hottō Kokushi. A fellow monk, though, advised Musō to develop his practice (of Zen) before approaching so renowned a priest. So, when he was twenty years of age, Musō traveled to Kyōto to study with the venerable priests Mu-in Eban at the temple of Kennin, with Tokeitokugo at the temple of Engaku, and, traveling to Kamakura and to the temple of Kenchō-ji, with the venerable priest Chido-oshō.

In 1299, while in Kamakura, Musō studied with the influential Chinese priest Yishan Yining. Ichizan Ichinei, as Yishan Yining was known in Japan, had become abbot of Kenchō-ji. Musō desired answers concerning suffering, but Ichizan Ichinei only replied calmly to Musō that within Zen Buddhism there were no “answers” to “questions.” Frustrated with this pedagogy, Musō ceased his studies with Ichizan Ichinei.

Kōhō Kennichi, a descendant of Go-Saga, subsequently became Musō’s influential teacher during this phase of his life. Kōhō’s priest name was Bukkoku Zenji (later, Kokushi), and Bukkoku was renowned for having studied Zen Buddhism under the venerable Chinese priests Wu-an P’u-ning and Wu-hsueh Tsu-yuan. Musō also approached Bukkoku expecting to receive direct answers to his direct questions, but was met with the same reply he received from Ichizan Ichinei. Bukkoku sternly told Musō that he must not expect others to provide the awareness he sought.

Musō then returned to live on mountains and within forests, this time traveling to the far north of Honshū. He built shelters, within which he lived. He sat within nature, often on what he termed “meditation rocks” (see Chapter 8, “Sitting in the Garden”).13 Musō vowed not to return to speak with Bukkoku until he had experienced the awareness he had sought from his teachers.

WANDERINGS OF LIGHT AND DARK

For more than twenty years, Musō lived mostly amid forests and mountains.14 During this time, he wrote of several initial experiences of awareness of Buddha-Nature. It was said that “once a person awakens to the field of Original Nature, he sees that Buddha-Nature, mind, ‘thusness’ [shinnyo] … as well as … the great earth, mountains, rivers, grass, tiles, or stones, are all the field of Original Nature.”15 During this phase of his life, Musō’s teachers, his examples of enlightenment, were trees and water and mountains.

He became aware of the subtle manner in which sunlight and shadow flowed as the surface of bamboo, ebbing to and fro with the wind. One evening, sitting at fireside near the Okita River, Musō contemplated flames flickering in the darkness. At moments, it would appear as if there was no distinction between wood and flame. Between light and dark.

Musō began to experience everyday existence as Buddha-Nature in that “living in this way … everything right and left, everywhere, was full of existence. And he heard the voice of existence itself.”16 Musō, though, felt that he had not yet experienced the awareness experienced by Shākyamuni under the Bodhi tree. Musō wrote of one experience where he fell asleep during a long session of zazen and, upon waking, became ashamed of having fallen asleep. Yet at that moment also, he began to question distinctions such as sleeping and waking, remembering and forgetting. He felt that if he had truly not made a distinction between wakefulness and sleeping, he would not have experienced the suffering of shame at having fallen asleep.

Musō began to watch the ebb and flow of his thoughts. He felt that he still was making distinctions that did not exist, except within his clouded mind. Distraught, he thought of returning to Bukkoku Kokushi to announce his defeat when, unexpectedly, he experienced a signal Zen Buddhist state of awareness.

The year was 1305. One night, while staying with friends, he rose from a long session of zazen “and stepped out into the garden of the house in which he was staying [my italics].”17 He sat for some time under a tree in the garden (again, reminiscent of Shākyamuni sitting under the Bodhi tree). Rising from his meditation, Musō moved to retire to the house. Darkness obscured his way, and he tripped over a piece of the roof that had fallen to the ground and … he fell to the ground.

A simple, ordinary act. Yet, Musō’s response was to … laugh, in surprise. In this sudden, spontaneous laughter Musō perhaps felt he had experienced the state of awareness Zen Buddhists term satori. Importantly for us, if so, he had experienced satori within a garden.

Satori is held to be awareness of “pure existence,” existence experienced directly and not filtered through ego-consciousness. “Original Nature [Buddha-Nature] is pure existence,” and experience of pure existence often is associated with overwhelming calmness, joy, and peace of heart and mind.18

And laughter. Buddhists often say, “laughter is the cancellation of ego.”19 In Zen Buddhism, “a smile or laugh … cancels the world of opposition … laughter rescues the mind.”20 Musō “fell through” his walls of expectation and illusion, and awoke to existence-as-it-is (shinnyo). He experienced existence-as-it-is without texts or ritual. He experienced existence-as-it-is … within nature.

It was the custom at the time to compose a poem upon the initial experience of what was believed to be satori, and Musō wrote:

Year after year

I dug in the earth

looking for the blue of heaven

only to feel

the pile of dirt

choking me

until once in the dead of night

I tripped on a broken brick

and kicked it into the air

and saw that without a thought

I had smashed the bones

of the empty sky21

Musō had been preoccupied with what we would term dualisms: “earth”/ “sky,” for instance. Existence was experienced as obstacle, as suffering, until a chance stumbling shattered illusion such that “the activity of consciousness is stopped and one ceases to be aware of time, space, and causation.”22 Musō’s experience spontaneously shattered “bones,” the conventional manner in which he had been experiencing illusion-as-reality. In a garden, Musō initially experienced “this state that we call pure existence.”23 We read, “you can appreciate … the beauties of nature with greatly increased understanding and delight. Therefore, it may be, the sound of a stone striking a bamboo trunk, or the sight of blossoms, makes a vivid impression on your mind … This impression is so overwhelming that the whole universe comes tumbling down.”24 Often, in laughter.

Musō journeyed back to Kamakura to relate his experience to Bukkoku Kokushi. Bukkoku acknowledged that Musō’s experience in the garden indeed had been satori and, in the traditional rite of succession, Bukkoku presented Musō with his Inka (印可, Seal of Enlightenment), one of his robes, and a portrait of himself.

GREEN MOUNTAINS BECOME YELLOW

After having received a seal of succession from the venerable Bukkoku Kokushi, Musō’s fame spread widely and people increasingly petitioned to study with him. Yet he continued to feel that “the great earth, mountains, rivers, grass … stones, are all the field of Original [Buddha] nature.”25 In 1312, Musō and several fellow priests went to live within forests and to practice sitting amid mountains. During this period, Musō founded Eihō-ji in 1314. Mostly alone now, throughout 1315 he lived around the Tōki River area.

Word reached Musō that Bukkoku Kokushi had died on December 20, 1316. Upon hearing of his teacher’s death, Musō wrote “green mountains have turned yellow so many times … When the mind is still the floor where I sit is endless space.”26 Musō’s Buddha-Mind appears now to be able to peacefully attend to what conventionally is conceived of as death in a manner quite different from his prior turmoil over the death of the venerable priest Gyōren. Musō lived the next several years within mountains and forests.

In 1325, at the request of Go-Daigo, Musō temporarily came down from the forest mountains to became abbot of Nanzen-ji in Kyōto. Returning to Kamakura in 1327, he was appointed abbot of Zuisen-ji. In 1329, monks petitioned Musō to become abbot of the influential temple of Engaku-ji. Recall that in 1333 Go-Daigo returned to Kyōto from exile in Chiburi. At this time, as well, the emperor presented himself to Musō as a pupil desirous of studying Zen Buddhism.27 Go-Daigo subsequently installed Musō as first abbot of Rinsen-ji, a small Buddhist complex near the present-day Temple of the Heavenly Dragon.

Musō was three times honored as Kokushi (国師, National Master). He received the honored title of Kokushi from Go-Daigo, as well as the title of Supreme Enlightened Teacher (正覚心宗国師, Shōgaku Shinshū Kokushi) from emperors Kōgon and Kōmyō. Musō also became known as Teacher to Seven Emperors (七朝帝師, Nanchō Teishi).

Vengeful Spirits and a Sky of Dream

The Temple of the Heavenly Dragon will be born amid violence and betrayal, suffering and death, as well as from the devotion of people to aesthetics, nature, and spirituality. In addition, interestingly, the temple will be conceived amid belief in the reality of dreams as a tangible presence affecting the sensibilities and decisions of people of influence.

In early 1339, Musō told fellow priests that he had had a startling dream about Emperor Go-Daigo, then in exile in Yoshino. Strangely, the emperor appeared in his imperial carriage amid the clouds then glided into the old compound of Go-Saga’s imperial villa near Turtle Mountain.28 Musō had dreamed of Go-Daigo seated within his imperial carriage as he glided into the compound; yet, rather than draped in his imperial regalia, in the dream Go-Daigo wore the clothing of a Buddhist monk! Go-Daigo died suddenly (August 16, 1339), in Yoshino, shortly after Musō’s pregnant dream. The dream was taken as a sign that the spirit of the emperor longed for the peaceful place important in his childhood.

Takauji of the Ashikaga especially was troubled by the death of Go-Daigo, because of his behavior toward the emperor. Takauji was preoccupied with his fate, with the still-present danger that the spirit of Go-Daigo posed to him.

People believed in ghosts (幽霊, yūrei) and in vengeful “hungry” spirits (餓鬼, gaki). The Record of Ancient Matters “reveals strong traces of a belief that certain deities and the spirits of the dead could lay a curse upon living men … The idea of possession by a vengeful spirit … was very prevalent.”29 In particular, a ghost abiding in the dwelling and habitat of its former life could be tormented by unease. It was desirable to try to put at ease spirits believed abiding in their former residences.

Takauji subsequently beseeched the spirit of Go-Daigo to find peace, and not seek revenge upon him for his treacherous behavior. “He [Takauji] knew that his conduct was reprehensible … He prayed for the mercy of Kannon [a Bodhisattva, a deity of compassion], asking that he should not be forced to suffer in the next world for his offenses in this. Life on earth was a dream.”30 In addition, Takauji thought to make an offering to compensate for his turning against the deceased emperor, conscripting his lands, and appointing himself shōgun. With the dream of Musō, and the solace-seeking behavior of Takauji, people of influence once again turned awareness toward the legendary regions west of Kyōto.

In an initial gesture of atonement, Takauji ordered the release of a number of prisoners, captives in war, as well as the release of a number of his political enemies. Further, Takauji ordered that cherry trees from Yoshino, where Emperor Go-Daigo had lived in exile, be replanted around the ruins of Go-Saga’s old villa at Turtle Mountain where Go-Daigo had lived as a child. Subsequently, the Bodhisattva Jizō (deity protecting travelers, especially children and pregnant females, through the realms of existence as well as saving souls from the torments of hell) came to Takauji in a dream. The Bodhisattva instructed that “thousands of small images [of Jizō] be cast,” intending that each statue “express his compassion for the soul of one man whose death in battle he had caused.”31 At the very least, sixty thousand people were slain during the war between the Northern and Southern Courts. In what we can interpret as an act of compassion, Takauji ordered the casting of a Jizō in commemoration of each life lost.

Still not yet at peace, Takauji sought out the venerable Musō Kokushi at Rinsen-ji, where Musō subsequently counseled Takauji to offer more substantive amends to the spirit of Go-Daigo. There was discussion of Musō’s dream of Go-Daigo entering into Go-Saga’s old imperial villa at Turtle Mountain as well as discussion of Takauji’s dream of Jizō.

Musō and Takauji increasingly became aware of their connection to each other. Both men, through dreams, indeed were connected to the land and landscape around the Mountain of Storms, with the old site of the imperial villa at the piedmont of Turtle Mountain, as well as with (the deceased emperor) Go-Daigo. Both men subsequently were struck by the idea, revealed through dreams, of resurrecting the deserted villa into an offering to Go-Daigo, a temple perhaps, “where the spirit of the emperor could be venerated and laid to rest.”32 Go-Daigo had loved nature, and he had spent much of his childhood on the grounds of the imperial villa at Turtle Mountain. After the reign of Go-Saga, the villa lay in mossy ruin. Buildings sagged with inattention and the grounds were deep brown and green, saturated with shades of neglect. Until the appearance of Ashikaga Takauji and Musō Kokushi, no one had attended to nor cared for the site west of the City of Purple Mountains and Crystal Streams.

In October of 1339, Emperor Kōmyō issued permission for Takauji to begin construction of a temple on the site of the old imperial villa at Turtle Mountain. By imperial decree, the future temple was a chokugan (a temple dedicated to an emperor) to the spirit of Go-Daigo as well as to the spirits of those who died during the war between the Northern and Southern Courts.

Deeply affecting landscapes often are constructed on a foundation of powerful emotions such as anger and love.33 Both Takauji and Musō felt connected to the old imperial villa at Turtle Mountain through a desire for peace, harmony, and compassion. “If one just forgets this self,” Musō wrote, “and rouses the intention to benefit all living beings, a great compassion arises within and imperceptibly unites with Buddha-Mind.”34 Musō felt compassion not only for the spirit of Go-Daigo but also for all those who died in the fighting between the Northern and Southern Courts; indeed, for all forms of being. Placing emphasis on compassion, Musō also sought to honor the spirits of the many animals, horses and oxen mostly, that suffered violent deaths during the war. Takauji, as well, sought peace of mind.

Services commemorating initial construction of the temple were held on January 5, 1339. At this time, a service also was held for Musō to honor his counsel to Takauji and to serve notice that Musō was to become the first abbot of the Buddhist temple. Musō reminded the assembled that, “everything the world contains—grass and trees, bricks and tile, all creatures, all actions and activities — are nothing but manifestations of the Law [the Dharma experienced by Buddha].”35 Musō declared that the temple initially would be a family temple for the Ashikaga, promote the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism, and function as a place within which Buddhist priests would be trained.

It was the custom at the time for a newly constructed Buddhist temple to have an honorary name (山号, sangō) referencing a venerated mountain to which it was linked. Reikizan (霊亀山, Mountain of the Spirit of the Turtle) was the mountain-name of the new complex, with respect to the long-standing veneration of Kameyama (as well as Ogurayama to the northwest). The formal name (寺号, jigō) of the temple was considered carefully as the name also would embody and participate in the spirit of the temple. The complex initially was named Precious Zen Temple of the Spirit of the Ryakuō Period (霊亀山暦応資聖禅寺, Reikizan Ryakuō Shisei Zenji). Shortly thereafter, though, the name of the complex was changed to Precious Zen Temple of the Heavenly Dragon (天龍資聖禅寺, Tenryū Shisei Zenji). The slight change in name was meant also to commemorate the temple as embodiment of the spirit of a dragon.

The Dragons of Dream

People at the time believed in the reality of dragons. People saw dragons. Dragons had long been associated with growth and fecundity as well as with benevolence and protection. The bones, teeth, and horns of dragons were apothecary treasures. The blood of a dragon was believed to congeal to amber, and the saliva of a dragon was the most potent of perfumes. Dragons were believed capable of transformation in form, and a dragon could be as large or as small as it wished. The appearance of a dragon, either in the life of dreams or in waking life, was a harbinger of good fortune.

The name “Temple of the Heavenly Dragon” accommodated the portentous appearance of dragons appearing in the dreams of Go-Daigo as well as Tadayoshi of the Ashikaga. Before his death, Go-Daigo had a portentous dream of a dragon that came to protect his life. Tadayoshi’s dreams were frequented by benevolent dragons of sky and water.

During the time of violent challenges to his rule, a dragon had appeared to Go-Daigo in a memorable dream: “In 1335, Emperor Go-Daigo had been invited to the house of Dainagon Saionji Kimmune, one of the Fujiwara. This invitation was given with the intention to kill His Majesty, who would have stepped upon a loose board of the floor and dropped down upon a row of swords. Fortunately, the Emperor was saved by the dragon of the pond in the park [Shinsen-in, Sacred Spring Park, a precinct of the Imperial Palace in Kyōto], who, in the night before he intended to go to the fatal house, appeared to him in a dream in the shape of a woman. She said to him: ‘Before you are tigers and wolves, behind you brown and spotted bears. Do not go tomorrow.’ At his question as to who she was, she answered that she lived for many years in the Sacred Spring Park.”36 The narrative further notes that Go-Daigo went to Sacred Spring Park for further guidance and to “pray to the Dragon-god. And lo! All of a sudden the water of the pond was disturbed, and the waves struck violently at the bank, although there was no wind. This agreed so strikingly with his dream that he did not proceed upon his way. So Go-Daigo returned to the Palace, and Saionji was banished to Izumo, which he never reached because he was killed on the road.”37 Lore and legend thus linked emperors to dragons. Dragons safeguarded emperors.

Emperor Jinmu (ca. 771–585 B.C.), the first emperor of Japan, was believed to be the grandson of the daughter of a kami of the sea—manifested in the guise of a dragon. The Record of Ancient Matters declares that “In the august reign of the Heavenly Sovereign who governed the Eight Great Islands from the Great Plain of Kiyomihara at Asuka, the Hidden Dragon [Jinmu Tennō] put on perfection, the Reiterated Thunder came at the appointed moment [of emperorship in 660 B.C.].”38 Emperor Ōjin (270–310) was said to have a dragon’s tail extending from his body, which he carefully kept hidden. A dragon was sighted at the beginning of the reign of Emperor Go-Uda (1267–1324).

And so, the spirit of Emperor Go-Daigo became synonymous with a dragon. The emerging temple was linked to Go-Daigo such that the complex demonstrably was a dragon temple.

Tadayoshi had been under the counsel of Musō, and their conversations on Zen Buddhism and on the recent civil war were recorded as Dream Conversations (Muchū Mondōshū).39 Like his brother Takauji, Tadayoshi felt abiding remorse with his own duplicit behavior toward the deceased Emperor Go-Daigo. At one point in their conversations, Musō underscored Tadayoshi’s connection to the emerging temple complex: “You are now respected by all of the people because of the good things you have done in your former life,” Musō tells Tadayoshi, “but you also have enemies … think about all the enemies you killed and all the soldiers who died fighting with you. Think about all their families and numerous descendants. If you honor their memories, you will comfort many people.”40 And the way to further honor memories of the dead as well as comfort the living was through the engagement of Tadayoshi in the birth of the emerging Buddhist temple complex.

In the dream of Tadayoshi, a mighty dragon of gold and silver rose from the waters of the Ōi River skirting the Mountain of Storms. Instead of flying off into the sky, the dragon glided into the garden pond of the old imperial villa at Turtle Mountain. The dragon living in the dream of Tadayoshi made its presence known during the genesis of the new temple complex. In the dream, the dragon surfaced within an area near a river and human-made pond of prior religious significance.

River dragons were believed to dwell within treasure-laden palaces (ryūgū) beneath the water, and veneration of the deities of the sea and rivers in time became associated with veneration of dragons. “Dragons were kami gods who lived in rivers and seas, valleys and mountains [in rivulets, lakes, and ponds].”41 A dragon rising from water became associated with rain, literal generativity.42 The rising of a dragon initiated a cycle of ascent and descent associated with what we would term the vast hydrologic cycle of nature itself—water rising in mist from the earth only to fall again, as rain. Witnessing a dragon rising from a river, even in the life of a dream, was an omen of emerging beneficence (fig. 37).

In the dream of Tadayoshi, a dragon rose from the river to fly off into the sky. Flying dragons were recorded as early as the sixth century. According to the Chronicles of Japan (Nihongi), at the beginning of the rein of Empress Saimei (ruled 655–61) a dragon appeared in the sky above the western peaks of the Katsuragi Mountains.43 The Katsuragi Mountains were the site of an early Buddhist complex (The High Temple of Katsuragi), and the subsequent sighting of dragons in the sky became associated with the appearance of Buddhism in Japan.

The snake-like form of the dragon in Japan is related to Nāga, the water-serpent deities of India. Nāga were believed to live on Mount Meru, the mythic mountain around which creation had formed. Nāga lived within golden palaces vibrating with ethereal music, ambrosia, and wish-fulfilling jewels and flowers. Nāga lived surrounded by a garden with “the dragon-haunted tree at its center being hung with jewels in which the life of the Golden Embryō is hidden.”44 Through Nāga, dragons in Japan came to be associated with gardens as well as with Buddhism.

FIGURE 37. “Dragons and Clouds.” Detail of a six-panel folding screen, by Tawaraya Sotatsu (ca. 1600–1643). 1630, ink on paper, 171.5 × 374.6 cm.

Early Buddhism conceived of Nāga as the guardians of Buddha. Indeed, Buddha was believed to have been incarnated as a Nāga king before incarnation as Siddhārtha Gautama. He was “bathed, as soon as born, by the Nāga king and queen, who later created a lotus leaf on which he might reveal himself.”45 Legend has it that, after his awareness of Buddha-Mind while sitting under the Bodhi tree, Shākyamuni traveled to Lake Mucilinda where he sat in meditation for seven days. Mucilinda, the seven-headed Nāga after whom the lake was named, “saw the Buddha’s light and rose to the surface, where he was so delighted that he caused it to rain for the whole seven days and protected the sage by curling his seven hoods, or heads, over him.”46 Disciples of Buddha subsequently “converted them to the faith and indeed made them its guardians.”47 The promise of the Nāga was that “until the dawn when Maitreya [“The Loving One,” a Buddhist deity embodying all-encompassing love] comes to preach the three sermons under the dragon flower tree, even so long I will guard this land and govern the workings of Buddhist law.”48 The hooded cobra-like visage of a Nāga/dragon sheltering and protecting Buddha remains a common, dramatic image (fig. 38).

FIGURE 38. “Buddha Protected by Naga.” Ninth century A.D., sandstone, 111 × 52 × 29 cm. Cambodia.

With respect to the association of dragons with Buddha and Buddhism, it was not uncommon for the name of a Buddhist temple to be “called after a dragon which was said to live there or to have appeared at the time the temple was built.”49 The sighting of a dragon in association with the consecration of a Buddhist temple, again, was considered a favorable omen. In 596, a Buddhist temple in Nara was being dedicated when a “purple cloud descended from the sky and covered the pagoda as well as the Buddha Hall; then the cloud … assumed the shape of a dragon … After awhile it vanished in a westerly direction.”50 In 1697, a Buddhist temple in Mino Province was being dedicated when “a dragon appeared with a pearl in its mouth, a very good sign indeed.”51 Until quite recently, people continued not only to believe in dragons but also to experience dragons. In the dream of Tadayoshi, therefore, it was a harbinger of good fortune that a dragon had descended into the old villa of Go-Saga, also associated with Emperor Go-Daigo.

The extent to which people deferred to dreams in renaming the emerging temple complex further reveals the power and influence of belief in the animistic reality of dream.52 The naming of the emerging complex accommodated long-standing belief in the beneficent appearance of dragons in association with commemoration of Buddhist temples as well as with the conception of dragons as the guardians of both Buddha and Buddhism.

Dragons and dreams were influential animistic presences in the final naming of temple. Dreams and dragons were fortuitous omens of the favored future life and significance of the temple.

Construction of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon began in late 1339, initially with the labor of one master carpenter and twelve assistants. Six years, though, were required for completion of the complex. We will meet dragons again as a vital aspect of the ongoing life of the temple.