Читать книгу Tenryu-ji - Norris Brock Johnson - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE POND IN THE GARDEN

Myriad stones appear to float on water softened by a shimmering late afternoon haze, caressing the pond. The garden is a mosaic of water and stones, foliage and sky, experienced as … tranquillity.

The pond in the garden before us appears sheltered by the deep roof eaves of the temple building within which we will envision ourselves sitting. We sit on tatami covering the expansive floor of the Quarters of the Abbot of the Temple, until recently the traditional residence of successive abbots of the temple. Shōji have been pulled back along tracks in the floor, opening the rear wall of this large room to the garden. Sitting quietly, we look across the veranda of the Abbot’s Quarters to contemplate the pond in the garden of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon (天龍寺, Tenryū-ji; figs. 3, 4).

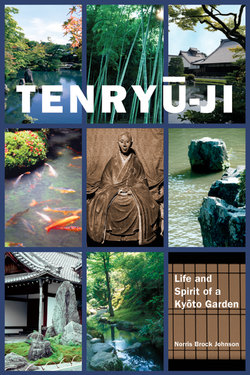

This book is a contemplative study of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon, Tenryū-ji, a Buddhist temple nestled within the mountains of western Kyōto, Japan.1 Tenryū-ji is the main temple of the Tenryū school of Rinzai Zen Buddhism, and the temple participated in significant historical events in Japan. The temple reminds us that landscape and building architecture were a vital presence in events significant to the history of Japan. We will witness the temple emerge across generations through its designed interrelationship of buildings, nature, human-created landscapes, and the participation of people as well as belief in the participatory presence of deities and venerated ancestors. The temple across generations will stimulate the thoughts and ideas, values, and behaviors of people. Sustained attention to Tenryū-ji reveals the manner in which a distinctive human-created space and place, the temple complex, conditioned in people distinct ways of conceptualizing as well as being in the world.

FIGURE 3. When experienced from within the rear room of the Abbot’s Quarters, the pond in the garden appears as a three-dimensional picture framed by roof eaves, projecting rafters, and the expansive veranda.

FIGURE 4. The west/northwest area of the pond, viewed from within the central rear room of the Abbot’s Quarters.

The heart of this book is the pond garden aspect of the temple, as “the design of the garden came to have both pictorial and historical importance, attracting people to Tenryū-ji and impressing them.”2The venerated pond garden participated in the genesis of several defining moments in pre-modern Japan. Quite apart from conventional conceptions of garden as epiphenomenal to other aspects of human life deemed vital such as, say, political economy, sustained study of the pond garden aspect of Tenryū-ji reveals the manner in which gardens have had an abiding effect on our imaginations as well as a determinative effect on human history.

Shimmering Garments of Silence

By way of introduction, let us walk through the complex to the pond in the garden. Passing under a front entrance gate to the temple, noise is muted quite suddenly. The sensation is that we have passed through a gossamer shroud, imperceptibly closing behind us to drape the temple from the world outside the gates. Sounds outside the entrance gate further are silenced the deeper we move into the temple (figs. 5–10).

Intricately knit footpaths of stone lead us deeper into the complex. In the distance, we see the upper portions and roof of the building presently serving as the public entrance to the pond garden. In the thirteenth century, an early version of this building (Kuri) housed kitchen and storage areas; presently, the building primarily houses administrative offices and serves as a public reception area for the temple. The facade of the present-day reception building is a contrast of white stucco walls laced crisply by dark timber framing, embraced by the deep green of surrounding trees of maple and pine.

The avenue between the entrance gate and the reception building, along which people walk to the central area of the temple, is lined with coniferous and deciduous trees. Glancing upward while walking within several areas here, we experience the billowing foliage of green under which we pass as a floral nest of sky. We move ever deeper, more intimately, into the verdant silence of the temple.

FIGURE 5. A map and aerial view of the present-day central area of the complex. Main entrances into the complex are to the east (toward the lower-center of the photograph). At present, public visitors to the temple use the entrance to the right of the center axis and approach the pond garden by walking around the southern (left) side of the Abbot’s Quarters.

FIGURE 6. The main buildings and features of nature making up the present-day principal aspects of the complex: (A) Mountain of Storms (Arashiyama); (B) Turtle Mountain (Kameyama); (C) Abbot’s Quarters (Dai Hōjō); (D) the pond (Sōgenchi); (E) Guest Quarters (Ko Hōjō); (F) present-day reception building (Kuri); (G) sand garden (karesansui); (H) present-day entrance route, pointing west; (I) Rinsen-ji; (J) present-day location of the Moon-Crossing Bridge; (K) Lecture Hall (Hattō).

Through subtlety of architectural design, we experience the landscape aspect of the temple as a sequence of gradually unfolding vistas. The sensate experience is that the landscape aspect of the temple is an exquisite three-dimensional painting, through which we move. The experience is akin to the manner in which we experience a hand-scrolled painting of a landscape, an emakimono (絵巻物, picture scroll). Emakimono influenced the design of gardens, during the eleventh to thirteenth centuries in particular. Emakimono, such as the important Genji Monogatari Emaki (Illustrated Tale of Genji), combine both characters and images painted on paper or silk, ranging nine to twelve meters in length, furled at the left-end onto a dowel rod. Emakimono were experienced by unfurling text and image such that landscapes and commentary flowed scene-by-scene between one’s hands. The landscape of an emakimono is not experienced all at once; similarly, the landscape aspect of the temple is not experienced all at once. Gates, foliage, and building architecture by design focus awareness on each area through which we pass. By design one is prompted, nonverbally, to pause briefly within defined areas of the temple so as to experience the landscape as though there is nothing else to the temple except this place and this space. This moment. And then … we move on.

The walkway opens to broad steps in front of the reception building entrance to the pond garden. Climbing the stone steps, then pausing to glance back along the tree-lined pathway, the world outside the front gates of the temple now cannot be seen or heard. Silence shimmers in the air and hangs in folds, a garment worn by the temple itself (figs. 11–13).3

We pass through the reception building, and enter areas preparatory to experience of the pond garden. Now, the walkway under our feet is pebbled stones shifting slightly under our weight, cushioning our footfalls. A rectangular expanse of gravel (枯山水, karesansui, dry-landscape garden) lies to the left of the footpath.4 The design of the landscape guides our movements, pace, and direction, as the walkway winds around and to the rear of the Abbot’s Quarters (figs. 14–16).

FIGURE 7. The present-day main public entrance to the temple.

FIGURE 8. This secondary gateway provides a quiet entrance into the temple, an alternative to the busy entrance near the bus stop (fig. 7). Maps of the complex name early versions of this entrance Honmon (本門, Origin Gate; Gate-to-Enlightenment).

FIGURE 9. Upon entering the complex, one passes over a bridge-covered stream. The avenue leads from the front gates to the central area of the complex, with the dramatic façade of the present-day reception building in the distance.

FIGURE 10. From this vantage the reception building appears embraced within a nest of trees, emphasizing the manner in which nature by design still is experienced as a constituent aspect of the temple.

FIGURE 11. The approach to and front area of the reception building, through which one passes to experience the pond garden.

The Quarters of the Abbot of the Temple (Dai Hōjō) is a magnificent building, elegant in varied hues of aged wood (figs. 16, 26, 29). The deep, sloping eaves of the roof are a haven for shadows and birds that occasionally fly, chirping, through and about the building.

The lines of the footpath and the lines of the Abbot’s Quarters visually converge in the distance, pointing our way to the present-day central area of the temple.

Myriad clusters of trees frame the rear of the Abbot’s Quarters. Visually, it appears that we will walk into the wooded area ahead but, at its end, the footpath abruptly turns to the right. And, as if unfolding into existence upon our approach, the pond in the garden appears quite suddenly before us (figs. 17–21).

FIGURE 12. This dramatic arrangement of stones in front of the reception building is intended to evoke the mythic mountain of Meru (figs. 75, 76).

FIGURE 13. The roof to the left shelters the east-facing front veranda of the Abbot’s Quarters. There are two types of garden within the present-day temple complex. The rectangular bed of gravel and sand (karesansui), to the right, is a recent addition to the temple. In a complementary fashion, this garden bed of gravel and sand was sited on the front eastern-side of the Abbot’s Quarters while the rear western-side of the Abbot’s Quarters faces the pond garden.

An oasis. An initial impression, feeling, about the pond is of an oasis. Stones of varied size and shape are strewn about in the water of the expansive pond, each and every stone long ago having been placed by hand. Large and small, dark as well as light in color, jagged as well as smooth of form and texture, the very presence of the aged stones compels attention. The more one sustains awareness of and contemplates the garden pond, the more one becomes aware of an intricacy of design and complexity of arrangement with respect to the stones in the water (figs. 22–24).

Water shimmers under expansive stands of trees, defining the far shoreline across the pond. The trees lead our eyes upward, directing our awareness to panoramic vistas of mountain and sky.

Visual awareness is complemented by faint sounds stimulating aural awareness of the pond garden:

“Plop” “Plop” “Plop”

Myriad fish, koi, on the pond’s surface leap up briefly into air and sunlight then flip downward into the water (fig. 25). One becomes aware of stillness, and one’s breathing.

For many people, as we will see, the experience of the pond garden aspect of the temple continues to impart feelings of renewal (心が洗われた気持ち, kokoro ga arawareta kimochi)—emotionally, physically, and spiritually.

Wafting gently through the trees, the wind is the scent of life.

The Life of a Garden

Organized into three parts, this book presents the origin, defining life experiences, and salient present-day aspects of an influential temple and its celebrated pond garden. Earth and stone, water, and human activity (as well as belief in the agency of deities and venerated ancestors) came together over time in fashioning a still vibrant landscape that continues to touch the feelings, and hearts, of people.

FIGURE 14. The front eastern-side of the Abbot’s Quarters. The temple Dharma Drum (Hokku), the white circle to the right-side end of the veranda, is sounded as a call for monks to assemble.

FIGURE 15. With shōji pulled back along their tracks in the floor, glimpses of the pond can be experienced through the Abbot’s Quarters as one walks to the western garden.

Consider the manner in which contemplative experiences of the pond garden touched Tsutomu Minakami, an award-winning writer who was a priest within the temple during the 1930s. Since 1345, Tenryū-ji has served as a residential arena for the training of priests. Priest Minakami wrote, “When I was young, the shadows of many people did not fall within the temple. There were only mendicant wicker-hatted priests coming into and going out of the temple. As a young priest, I had opportunity to see many gardens in Zen temples but in the Tenryū-ji garden stones, trees, and water are placed in a perfect harmony [和, wa], still alive after hundreds of years.”5

Priest Minakami personified the garden, and he related animistically to the garden as he would relate to a person. The concept of animism will be of ongoing importance to our study of the temple pond garden. Here, “animists are people who recognize that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and that life is always lived in relationship with others.”6 Conceptualizing animism as a sympathetic relationship rescues a vital existential theory of being from prior dismissals as “primitive mentality.” Anima, the Breath of Life, is synonymous with spirit as a vital aspect of life; as such, animism challenges conceptions of phenomena labeled “nonanimate.” Life lived in relationship with others includes others that perhaps are stones or ancestors or spirit.

As we attend to the pond garden aspect of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon, animism will be manifest in the manners in which the garden over time is perceived and experienced by people as vital and affecting as well as, importantly, in the interdependent personto-person manner in which people behave toward the garden and aspects of nature held to be sacred. Priest Minakami, for instance, experienced the garden “in a knowing manner, as hundreds of thoughts appear and disappear; only the garden, the quiet garden, is left before me. The garden remains there, silently.”7 Priest Minakami experienced what we might term the soul (魂, tamashii) of the complex, in that “the temple was so quiet, and refreshing. The tranquillity of the Dai Hōjō in the pine trees, and the path paved with stones … turning into something more than just a view of the garden [my italics].”8Something more. Throughout its tumultuous existence, as we will see, the pond garden aspect of the temple was and continues to be experienced animistically by people as vital spirit (精霊, seirei)—the “something more,” I feel, of which Priest Minakami wrote.9

Part I reconstructs the early settlement activity on the land on which the present-day temple buildings and pond garden rest. Tenryū-ji proper was constructed from 1340 to 1345, though the area west of Kyōto within which the temple emerged was the site of what we would term religious (Shintō, principally) activity as early as the tenth century.

Chapters composing Part I recount the manner in which salient events and people of influence defined the character of the region within which the temple and pond garden came into being. In turn, the mountainous region west of Kyōto exercised considerable influence on the character of twelfth- and thirteenth-century Japan. Part I is the compelling account of the birth and early life of a landscape continuing as “a powerful domain which includes felt values, dreams … and events, to which affect has accrued.”10 In addition to matters of design and construction, emotion also is a vital aspect of the origin and life of landscapes. Compassion and love, as well as fear and guilt, specifically, generated influential activity and historically important events that participated in the genesis of the landscape aspect of the temple.

FIGURE 16. The front eastern-side of the Abbot’s Quarters.

FIGURE 17. People customarily move rather quietly toward the pond in the garden.

Part II presents core features of the pond garden aspect of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon from present-day points of view. Chapters composing Part II are framed by my ongoing experiences with, and interpretations of, the pond garden as well as by a priest with whom I studied while staying periodically within the temple. While teaching at Waseda University and the University of Tōkyō, Komaba, I first came upon Tenryū-ji quite unexpectedly late one spring afternoon in 1985 while exploring the forested regions west of Kyōto. I only had sought to find refreshment within the temple, tea and rice cakes perhaps, and to rest from the day’s sojourn.

Initial experiences of the pond garden were deeply affecting for me and I continued to revisit the temple, initially among throngs of visitors (figs. 7, 17). Young couples often entered the temple to stroll hand-in-hand through the park-like wooded upper areas of the complex. School buses, shiny in reflecting midmorning sunlight, would line up in rows in the larger parking area. Quiet and orderly in crisp uniforms, young schoolchildren would file from the buses. Teachers carried poles flying the banner and logo of each school. Students would line up behind the banners then begin their study-excursion through the temple. The pond garden and temple buildings are important historically, as we will see, and are a planned educational experience for many schoolchildren. Many afternoons women, mostly, and a few men would enter the temple to consult with priests, to pray, to copy then recite sūtra attributed to Buddha, or to sip green tea (matcha) while sitting quietly on the veranda of the Abbot’s Quarters overlooking the pond in the garden.

FIGURE 18. A glimpse of the pond and a view toward the south/southwest, from in front of the rear of the Abbot’s Quarters.

FIGURE 19. The pond in the garden. The view is toward the south/southwest.

FIGURE 20. The pond in the garden. The view is toward the west with the piedmont of Turtle Mountain, blanketed with trees, as background.

FIGURE 21. The pond in the garden. The view is toward the northwest.

FIGURE 22. Moss and foliage contribute an organic quality to aged stones, stones appearing to rest on the water of the pond. The faint line of a spider’s web reveals a subtle, unintended though engaging manner in which several stones in the pond are interlinked.

FIGURE 23. Variegated light and shadow delineate the faceted intricacies of stones in the pond.

My explorations of the temple complex grew more prolonged and intense and, at dusk, as the front gates were closing, monks often had to usher me up and out from sitting before the garden. One morning, I asked the (exclusively Japanese-speaking, at the time) staff if there was anyone who could tell me about the pond garden in particular, with whom I would be permitted to speak. I was introduced to a senior priest known for his knowledge of the pond garden. After a time, “the priest” (as I will refer to him) began to tutor me into “seeing” the life and ways of the landscape by encouraging my prolonged sitting before the pond so as to let the garden reveal itself to me.11 I was given access to temple documents for study and I began researching, collecting and translating, and interpreting the few extant articles on the pond garden principally gathered at the libraries at Waseda and the University of Tōkyō. Subsequently permitted to move about the grounds, often alone, after visitors had left, I began to draw maps and photographically document the temple and specific features of the pond garden.

Thus I began ongoing experiences with, and intensive study of, the temple and pond garden, research and writing that continued over the next several decades. I began to devote successive years to learning that which the temple buildings and pond garden continued to demand of me. In attempting to “capture” the temple buildings and pond garden with photographic images and written words, friends in Japan often said I did not notice that the pond garden had “captured my heart.”

When in Japan I returned regularly to the pond garden, as if to a touchstone. Away from Japan, I remained mindful of and continued to feel the presence, the quietude and serenity, of the pond garden. When in Kyōto I was permitted to stay within the temple periodically where, on a futon on a floor of the Guest Quarters, in the early haze of morning, “in dreams I drift on, waking at the feet of the great stones” in the pond garden.12 Arising, I would meet with the priest as he sat and shared with me his vision of and experiences with the pond garden.

FIGURE 24. Stones in the pond, peaking above-water, were set carefully, braced by myriad below water-level stabilizing stones.

FIGURE 25. Koi, sunning in the warm upper waters of the pond.

While staying within the temple, I often recalled that the garden scholar Kinsaku Nakane also embraced a firsthand lived-experience method of researching temple gardens. Professor Nakane, for instance, “found a house nearby and visited that garden [Kokedera, the “moss garden,” within Saihō-ji, the Temple of the Western Fragrance] every day for over a year. Thus even now I know it down to the smallest rocks. If one really throws oneself into it, with much effort the garden’s essence suddenly becomes clear. It is essential to devote oneself in this way.”13 Like Nakane-san, over the years I found that the temple pond garden indeed did begin to reveal its life and spirit to me … through a relationship of intimate, devoted, and prolonged direct experience.

Chapters in Part II interpret in detail seven especially significant aspects of the garden highlighted by the priest—stones, compositions of stone, as well as the pond itself. The temple landscape and aspects of the present-day pond garden are envisioned by the priest principally as manifestations of the Buddha-Nature (仏所, Bussho) of the still-venerated priest Musō Soseki (1275–1351). Soseki was the first abbot of the temple, and, despite scholarly controversy, the priest with whom I studied argued firmly that Soseki “made” the pond garden. Part II looks at associations made by the priest between selected aspects of the pond garden and Rinzai Zen Buddhist states of awareness (見性, kenshō, and 悟り, satori, in particular).

Part III elaborates upon the pond garden aspect of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon as a considerable contribution to our understanding of the very idea of “garden.” The gardens of Japan continue to capture the attention, stimulate the feelings, and touch the hearts of people not only in Japan but throughout the world. In 1994 the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated the pond garden aspect of Tenryū-ji a World Heritage Site, “internationally recognized as a place of exceptional and universal value; a cultural-heritage site worthy of preservation for the benefit of mankind.”

It is as if the pond garden asks … “Why is the making of gardens, as well as our emotional experiences within gardens, a perennial human activity? Why are gardens so prominent in the human imagination, especially our religious imagination? In particular, why is experience of the temple gardens of Japan, for innumerable people from a variety of cultures, so charged with … sacredness (神聖, shinsei)?” In Mirei Shigemori’s translation of and commentary on The Book of Garden (Sakuteiki), he declares, “we do not yet understand the true meaning of garden making … I raise a question for everyone to help in addressing it.”14 Part III of this book is my anthropological response to Shigemori’s call for investigations into the idea of garden.

Part III concludes that the landscape aspect of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon embodies and preserves materially a primordial conception of garden, a conception of a garden centered around stones rather than foliage. Mirroring our walk to the pond garden aspect of the temple, we conclude our contemplative experience of Tenryū-ji by continuing through the pond garden, conceptually, to venture deep into prehistory to experience primordial conceptions of garden in the Sumerian accounts of the Garden of Inanna and the Garden of the Sun experienced by Gilgamesh. In the Sumerian literature, we find that a primordial conception of “garden” as a garden of stones antedates our conventional conception of “garden” as foliage.

The landscape aspect of the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon, a garden privileging stones, materially preserves an archetypal conception of garden as the animistic embodiment of spirit, deities, and venerated ancestors within which people participate. The primordial idea of garden is what we now would term a sacred space or place.

Acknowledgments

Research for this book was conducted in the New Territories of Hong Kong, in southeastern China, as well as in Japan. I remain indebted to the Japan–United States Educational Commission and the Fulbright Office in Tōkyō.

When in Kyōto I was invited to live in the home of Mr. and Mrs. Kenya Takeichi, in Uji, south of the city. I am indebted to the Takeichi family, who cared for me as family. Dr. Nobou Eguchi, Professor of Anthropology at Ritsumeikan University, also invited me to stay with him and his family in Kyōto. I am grateful for my friend, priest Takanobu Kogawa, then at Daikaku-ji, who, among other research assistance, secured for me permission to access and study firsthand several influential gardens in Buddhist temples whose gates at the time were closed to the public over an ongoing taxation dispute with the city of Kyōto. I always will treasure the collegial friendship shown to me by Professor Teiji Itoh, Department of Architecture at Kōgakuin University in Tōkyō, who devoted considerable energy and time helping me with my then-budding project on Tenryū-ji. For their collegiality and friendship, I also thank Professor Akio Hayashi of Waseda University and Professors Nagayo Homma and Iwao Matsuzaki at the University of Tōkyō. David A. Slawson provided valuable critical commentary early on in my research. Ms. Kei Nagami, Mr. Tatsuya Nakagawa, and Ms. Rumi Yasutake aided me in gathering and translating, along with Mrs. Makiko Humphreys, many of the historical materials on which this book is based. Mrs. Mitsuko Endo, Mrs. Akiko Nomiya, and Professor Daishiro Nomiya are friends dear to me who aided in the translation of difficult source materials, older kyūjitai (旧字体, old character form) especially. I alone am responsible for any errors in this book.

FIGURE 26. The Abbot’s Quarters (Dai Hōjō), to the right, is the larger wing of the central building complex. The smaller wing of the interlinked buildings, to the left, presently serves as Guest Quarters (Ko Hōjō).

Grants from the Japan Center, North Carolina State University and from the Northeast Asia Council of the Association of Asian Studies sustained my research. At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a Z. Smith Reynolds Award, several Faculty Fellowships, a Chapman Fellowship from the Institute for the Arts and Humanities, and several research grants from the University Research Council supported work on early manuscripts of this book. A fellowship year in residence at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C., enabled sustained work on completion of this book. I thank Dr. John Dixon Hunt, then Director of Studies in Landscape Architecture at Dumbarton Oaks, for our many conversations on gardens, art, and landscape architecture. Dr. Michel Conan, subsequent Director of Studies in Landscape Architecture at Dumbarton Oaks, carefully read and offered invaluable insights on the final manuscript of this book. I remain thankful to Keir Davidson, for his fine-grained critical reading of and gracious comments on the final manuscript.

I remain deeply appreciative of my always-welcoming home in the woods, which has provided over thirty years of shelter, respite, and nourishment of body, soul, and spirit as well as a constant stimulus for work. Apart from the aforementioned places, all of the work on this book took place at home amid windows filled with soothing vistas of myriad tree leaves of oak and cedar and pine and, at night, luminous sheets of moonlight filtering through the windows, often literally touching my writing. The house and land always require manual labor, fortunately—the physical work, for instance, of designing and planning home repair and renovation projects; working the land; pruning trees … and moving rocks and stones. The house and land participated greatly in the writing of this book by demanding, then reinforcing attention to the exquisite microcosm of myriad details of the part-to-part and part-to-whole interdependent relationships comprising the construction processes. Whether working with board or word, the house and land provided a setting and ongoing opportunities for the direct physical experiences of coupling ideas and feelings with materiality.15 Physical work/effort also is an important aspect of Zen Buddhism, as we will see.

Completion of this book would not have been possible without the encouragement and support of Dr. T. Elaine Prewitt, Ms. Stephanie Parrish Taylor, and Reverend William J. Vance. I am grateful to Peter Goodman and the staff at Stone Bridge Press for their sustained attention to and enormous energy involved in the myriad details of preparing the mauscript and images for publication.

This book exists because of the support of many people at Tenryū temple, notably the priest with whom I studied.

Tenryū-ji: Life and Spirit of a Kyōto Garden has been composed to engender in the reader a vicarious, felt-experience of a venerated Buddhist temple and pond garden. The temple and pond garden we will experience are not inscrutable, as “the world of affect is common to all people … anyone from any culture is bound to experience a basic substratum of rapport with the affecting presence of any culture.”16Marcel Proust once declared, “I believe each of us has charge of the souls that he particularly loves, has charge of making them known, and loved.”17 The pond garden in the temple continues to affect my life and spirit. I am privileged to have participated in the life and spirit of the temple and in making the pond garden better known and loved through the words and images of this book.18 Throughout its genesis and tumultuous life history, the pond garden within the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon always has touched a variety of people from a variety of cultures directly, as Rinzai Zen Buddhists would put it, through one’s heart (心, kokoro).

NORRIS BROCK JOHNSON

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Season of the Redbuds Blooming (March), 2012