Читать книгу Oladipo Agboluaje: Plays One - Oladipo Agboluaje - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеOladipo Agboluaje belongs arguably to the third generation or category of playwrights of African and British heritage1 whose dramaturgies differ from the writings of first- and second-generation writers of African and Asian descents; the latter’s subjects and dramatic styles were shaped and defined primarily by their experiences of colonialism. The works of first-generation writers (poets, novelists and playwrights of mixed African and British heritage in Britain from the late 1930s to the early 1960s were characterised by nostalgia and an interest in pre-colonial histories and cultures broken and fragmented by colonialism. Among these were Jamaican-born poet James Berry, Andrew Salkey and Stuart Hall, Edward Kamau Braithwaite, Wilson Harris, and Edgar Mettleholzer of Guyana, Samuel Selvon, CLR James, and VS Naipaul of Trinidad, and Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka of Nigeria. These writers were non-pretentious about their cultural agendas as they set about de-mystifying, explaining, re-interpreting and validating the cultural experiences of pre-colonial societies, their histories and myths. Some of their subjects and themes, although designed to provide readers with authentic representations of pre-colonised cultures, were overtly anti-colonial in sentiments and played on cultural binaries. Others, motivated by a sense of social responsibility and drawn by compulsion to explain the cultures of indigenous societies, produced writings that sought to contest the misrepresentations perpetrated and perpetuated in colonial histories written mostly from the viewpoints of colonial administrators and anthropologists.

Their successors, the second-generation writers among whom are Caryl Churchill, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Buchi Emecheta, Mustapha Mutura, Edgar White, Caryl Phillips, and Hanif Kureishi, set upon a different course, that of retrieving and re-writing pre-colonial, colonial, migrant, and dislocation experiences using the linguistic and narrative tropes of erstwhile colonisers as well as the hybridized languages they produced. Their works conveyed a radical and ideological fervour that was both essential in the development of post-colonialism as a literary and later subsequently as a multidisciplinary, multi-reading framework for analysing the political, social, economic, and literary developments of postcolonial societies. Second-generation writers of African and Asian descents include those born during colonialism and their countries’ struggles for independence and those born in the immediate aftermaths of political independence. The Marxist radicalism espoused in some of the writings by second-generation authors of dual heritage is motivated by factors such as the ideological impetus and social activism of their predecessors, resisting cultural hegemonies and homogenisation of their experiences. Another important factor is their rejection of other and marginal2 as critical categories for describing their historical experiences in relation to mainstream white society. Their impacts on the literary scene produced a polyglot of writings on new subjectivities and relationships and generated a distinctively British multi-narrative framed by Britain’s former colonial enterprise.

Although Black British writing (I’m using the term here in a very broad sense) started with social awakening and occasional apologetics by first-generation writers, second-generation writers resented the second-class citizenship bestowed on non-white communities in Britain. Second-generation writers confronted their marginalisation with bold assertions of their rights of being and inclusion. Some of the changes in writing styles were accomplished through a combination of abrasive self-determinism and cultural radicalisms that Alex Sierz (2001) would describe later as ‘in-yer-face’. These approaches and the contributions of social and sociological theorists such as Edward Said (1991) (on Orientalism) and James Stuart Hall (1993) (on Cultural Identity and Diaspora) to mention just a few, inevitably expanded the literary space and subjects of work by writers of African and Asian descents in Britain. Their writings went from them-us, centre-margin and dominant-other binaries to an exploration of postcolonial and postmodern conditions, from social tensions and sub-cultures to resisting racial hegemonies and essentialisms as well as interrogating gender, ideology, identity, sexuality, migration and diaspora, etc from several perspectives.

By the late 1990s postcolonialism and postmodernism changed and expanded the literary space in Britain and globally. Debates continue as to whether postmodernism has rendered postcolonialism ‘posthistoric’ in which case, the stage of human history it ‘claimed to offer explanation and understanding’ (Breisach, 2003:10) for has ended. Edward Said (1993) regards postmodernism’s claims to a post-history era as another hegemonic instrument designed by the West for global dominance. Existentialism and human conditions, sociocultural relations between individuals and people groups, societal and inter- and intra-community tensions, diaspora concerns and geopolitics are some of the common subjects interrogated in postcolonialism and postmodernism. Whatever their relations both discourses, together, have expanded the space for new writings in prose, poetry, live art, and dramatic texts and have produced, in their wakes, what I consider to be a third generation of writers distinguishable from their first- and second-generation forebears in three important respects. Firstly, while the first generation accepted and lamented their sojourner second-class citizenship, the second generation rejected all that and asserted their rights of citizenship, of belonging and place (see Proctor, 2000 and McMillan, 2006). Secondly, third-generation writers are unequivocal and confident about their place in society; they celebrate their dual heritage with vigour and ideological radicalism, whilst abjuring the angst of their predecessors. Thirdly, third-generation writers and writings adopt different tropes, from indigenous African and Asian conventions as well as from postcolonialism and postmodernism, they draw their subjects and inspirations from both discourses and write specifically for heterogeneous audiences and multicultural societies with different layers of interdependencies. Their constituencies are polyphonic, simultaneously local and diasporic. Even when they historicise particular experiences or are set in home continents and societies in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean – as are two of the plays in this volume – their subjects and characters link cultural geographies in a literary space of incredibly diverse stylistic influences in which indigenous, postcolonial and postmodern conventions converge to create a literary topography that is simultaneously local and ‘glocal’, the term used by Giovanna Buonanno, Victoria Sams and Christane Schlote (2011: 1, 14) to describe British Asian theatre’s capacity to mirror cultural peculiarities without losing its global frame.

In the online article ‘Black British Literature since Windrush’ written as part of the BBC Windrush season for the Summer of 1998, Onyekachi Wambu (1998) highlighted what I consider key characteristics of third-generation Black British writing: ‘it announced a literature that would look back to its source, but would be far more self-confident about its own position in Britain. It wouldn’t be marginalised as ‘Black’, ‘Commonwealth’ or any other kind of literature that put it at the edges. It would be a fully fledged member of the broad range of British writing.’ [http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/modern/literature_01.shtml.] Their subjects derive directly and indirectly from the unfinished socio-political and cultural agendas started by first-generation but tackled more fully by second-generation writers; existential angsts, social deprivations, problems of agency, racism, identity crisis, racial tensions, diaspora and the politics of migration and dislocation and their off-shoots of family and group dynamics, social fragmentations, cultural radicalism, religious fundamentalism, sexualities and critical self-examination. Third-generation writers are neither segregationist and insular nor motivated by celebrating cultural monolithism and the past. Although rooted in the struggles and subjects of their predecessors, as we see in the works of Fred D’Aguiar, Tunde Ikoli, Paul Boakye, Ayub Khan-Din, Hanif Kureishi, Meera Syal and many more, these writers rewrite Britain (Proctor, 2000; Sierz, 2011) and destabilise hegemonies and geographies of place, time, history and location. In essence, contesting territorialities in what Michael McMillan (2006) describes with regards to Black British writers and performers, as ‘reimagining of the self in a cultural and political context, where identities are continuously fragmented and hybridised’ (McMillan, 2006: 60).

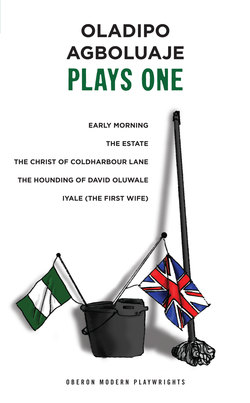

In this increasingly polyphonic and pluralistic theatrical landscape the number of theatre companies, such as Talawa, Tiata Fahodzi, Tara, and Tamasha that aim their works primarily at more than one of the many sections of Britain’s multicultural society, has grown. The creative possibilities for writers and the abundance of materials thrown up by new spaces and historiographies are endless and not lost on Oladipo Agboluaje who, since his debut in 2003, has become one of the most profilic of the third generation of Black British playwrights referred to here. His plays, no less so the five in this volume, Early Morning, The Estate, The Christ of Coldharbour Lane, The Hounding of David Oluwale, and Iyale (The First Wife), can be grouped under a distinct category of postcolonial, postmodern writings on Nigerian-British diaspora experiences. The plays reveal distinguishing characteristics that have come to define Agboluaje’s dramaturgy. Among these are an over-arching concern for interrogating the impacts of macro conditions on individuals and sections of British society alike, in other words, using the microscopic as point and canvas from which to interrogate the forces and conditions that shape relations at all levels. His plays can be read and staged against many backdrops; they convey non-polemical, ideologically centrist but unmistakeably Nigerian-British perspectives on many subjects from twenty-first century postcolonial conditions to tensions surrounding dual heritages, cultural nationalism and radicalism, religious fundamentalism and diaspora concerns. His episodic storytelling style and plots derive from his dual cultural background and education in Nigeria and Britain. His characters and stage directions reveal anxieties about directors and performers misunderstanding his apolitical centrist stance or worse still, turning the spotlight from critical self-examination and individual responsibility to politics.

Since his first play, Early Morning (2003), Agboluaje has written over 30 literary pieces including stage and radio plays, short stories and films. His plays have been staged to full houses and with good reviews in Europe, Nigeria and the US. The plays in this volume vary in style and subject and reveal a stylistic development that started with experimentation in episodic structure in Early Morning to complex interplay of storytelling and presentational staging in The Estate and The Hounding of David Oluwale. Agboluaje’s defining dramatic features include combining subtle comedy and loquacious humour, flashbacks, archetypal and symbolic characterization, and minimal staging. His dramaturgy emphasizes the dialogic interplay of character and setting as politicized sites. His narratives reveal both an attention to detail and emphasis on physical vocabulary for rendering his colourful, complex characters and the social forces that shaped them. His settings are more than mere physical constructs; they are best presented as part of the semiotic fabric of characters and narratives. One of his strongest dramaturgical tools is to combine short, pacey rhythmic dialogues into well-made storylines. The desire for a strong storyline drives, to some extent, his use of storytelling techniques such as flashbacks, dramatized narrations and dream sequences. Storyline is employed more overtly as a dramatic facility is The Estate and The Hounding of David Oluwale and in the prequel, Iyale (The First Wife).

A FEW WORDS ON THE PLAYS IN THIS VOLUME

Early Morning is about three Nigeria-born office cleaners who question their decisions to leave better-paid jobs and lifestyles in Nigeria for menial jobs in the UK. The sudden realisation by the three office workers (Kola, Ojo, and Mama Paul) that their wild dreams about a Britain of unimaginable opportunities are wide of the mark generates a tense atmosphere of anger, bitter disappointment, bickering and uncomfortable self-examination. Early Morning satirises the seedy, underpaid underside of capitalism; it is unsympathetic with the characters’ claim that every black person in the UK workplace is an innocent victim of racism and discrimination. Agboluaje focuses instead on the illogical expectations of the characters, black and white. Far from implying that the conditions of modern-day migrants, the majority of whom live in Britain legally, are only marginally different from the experiences of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century slaves and indentured labourers as one of the characters claims, the playwright uses the workers’ experiences to deconstruct cultural myopia and assumptions about the rights and wrongs of history. The simplest of his full-length plays, Early Morning is the start of Agboluaje’s experimentation with dramatic features that would grow in sophistication in later works. These include minimal staging, symbolic characterisation, critical self-examination, rejection of polemics, and play on humour and slapstick and the physicality of language. Other dramatic features are the interests in diaspora subjects and settings, identity crisis, characters caught in shifting diaspora subjectivities and quest for a ‘total’ theatre dialectic that celebrates theatrical syncretism and hybridity as shown in the integration of indigenous African and western performance conventions, such as African episodic structures and European plot devices.

The Estate is a vibrant, colourful play set in modern Nigeria in which a family gathers to honour the memory of their late patriarch, Chief Adeyemi. In the play Helen, former house-girl and now young widow of Chief Adeyemi plans a lavish public celebration of her late husband’s meritorious legacy. Despite the façade of civilised normality, the stage is set for shocking secrets as each turn of event reveals the sham beneath the actions and statements of the motley, disingenuous characters. As tensions grow and recriminations fly, Agboluaje unpeels layers of seedy dealings, greed, sibling rivalries, unexpected alliances and union between unlikely characters, betrayals and intrigues underneath the peaceful polygamous family set-up and the rise of a new socio-economic order as power shifts to the late chief’s former servant, now Pastor and de-facto owner of the estate. The stage turns into a platform for characters to play out the dying throes of their fading dreams; old cores are dragged out for settling and once-secure alliances are exposed as shams. The Estate is a very dynamic play, the episodic structure, strong storyline and rich pickings of subjects and complex multi-dimensional characters such as Pakimi who gives religion and pastors a bad name and the domestic servants cast in the moulds of cunning conniving servants of old comedy will delight producers, directors and actors alike. Like good comedy of the serious and funny category in which events take unexpected turns and supposedly harmless statements lead to surprising revelations, the play handles characters and their shenanigans with theatrical dexterity.

Power relations and intrigue, marginalisation, corruption and manipulation are expounded in the tragic social satire, The Christ of Coldharbour Lane. Set in the seedy underworld of Brixton, England where it is difficult to separate religion and manipulation, and where social deprivation often dovetails into crime, the play is unusual in its combination of a complex plot and episodic structure. The result is a complicated, fairly difficult play in which Agboluaje communicates his satirical take on the connection between poverty and faith in the supernatural and people’s reliance on charlatans and deluded schizophrenics like the main character, Omotunde, for answers to their problems. The playwright retains his interest in motley characters; this time they are not only hapless and trapped, their situation and setting are used as barometers for exploring how the damaging effects of government’s policy on gentrification impacts the very marginal sections of society the policy was designed to help. In the play Agboluaje explores competing subjectivities, none clearly defined and none capable of surviving in the socio-economic chaos of a specifically postmodern setting. The tragic outcome plays out on all levels and there is neither hope nor redemption: Dona, convert to the Mission and trainee for leadership; hardened sex-worker, Maria; and Sarah, wheel-chair bound, unemployed dole collector, all surrender their capacities for action whilst creating the platform for religious hacks and con artists to thrive.

The Hounding of David Oluwale, a stage adaptation of Kester Aspden’s novel of the same title is a documentary drama based on the discovery on May 4 1969, of the battered body of 38-year-old schizophrenic, David Oluwale in the river. The play follows the style of a forensic investigation and relies on official records and eyewitness accounts to unearth the official white-wash surrounding the verdict of death by misadventure reached by the police inquiry into the victim’s death. In the style of a true documentary, the play returns to the scenes of incidents and uses witnesses’ accounts and official records to reconstruct the facts, one of such witnesses being David Oluwale’s ghost who guides DCS John Perkins and the audience on a public inquiry into the circumstances of his death. The play avoids the polemics and theatrics of head-on confrontation of racial discrimination, stereotyping and prejudice. Avoiding the distraction in such an approach Agboluaje uses the legal framework and setting of the court to probe the victim and his victimisers and in the process pieces together various raw evidences and compelling counter-arguments that expose the institutional racism and stereotyping reminiscent of the 1998 public inquiry into the racist killing of 18-year-old black teenager, Stephen Lawrence in 1993 in Eltham, south-east London. However, unlike Sir William Macpherson who came to the damning conclusion that the police in the Stephen Lawrence case was institutionally racist after examining the original Metropolitan Police Service investigation, the un-named Judge in The Hounding of David Oluwale goes through the same judicial process before coming to a slightly different conclusion; he avoids mentioning the role racism played in David’s death and blamed the actions of a few police officers instead of the whole police force. As in his other plays in this volume, Agboluaje uses the microcosm or the actions of a small section of the population to expose the cultural tensions beneath the surface of society.

Similar to The Estate, the prequel Iyale (The First Wife) is a fastmoving play with many twists. It does not disappoint and reveals the shaky family foundations and social deprivations beneath the behaviours, cunning and graft exhibited by characters in The Estate. Iyale foregrounds the events and characters in The Estate by exposing the genesis of the self-serving selfishness, greed, betrayal and official corruption in The Estate as the surface symptoms of deep-rooted scars and problems on the nation’s psyche. In effect, the muted fatuousness and excesses we see in The Estate are not mere aberrations, they can be traced to a historical pattern of abuses characterized by political high-handedness and excesses that the population turn a blind eye to and condone for personal and cultural reasons. In effect, the actions of the characters; Pastor Pakimi’s betrayal of his religious vow and calling, the corruption of the ruling political and military elites, the sexual predation of Chief Adeyemi and the domestic abuse he inflicts on his stiff upper-lipped conscientious first wife, the shameless disloyalty and infidelity displayed by sexually voracious house-girl and lover to Pakimi, Chief Adeyemi and his son, Yinka, are all symptomatic of bigger problems at all levels of society. In the midst of such huge moral, ethical, and religious deficits and absence of cultural and political censures, religious quacks, corrupt politicians and soldiers, and social miscreants become the shocking role models to a citizenship that is driven only by its own mindless pursuit of excess. It is not surprising that the citizens including the socially disadvantaged servants like Helen and Pakimi will stop at nothing to achieve their nefarious personal goals, irrespective of the damage they cause on the way. A reading of Iyale (The First Wife) and The Estate together before performing either will offer directors and actors useful insights and workshop materials for characters and situations.

In conclusion, Agboluaje’s plays can be described as episodic with a strong narrative thread. His writing style is framed by a subtly evocative exploration of subjects, themes and characters that is akin to a witnessing of facts than a debate. His characters and language are physical, his narrative or storylines reveal without the need for polemics or soapbox rhetoric. His images speak for themselves and require little embellishing; even when they are deployed as counter-narratives their purpose seems to be to witness and show. The plays in this volume strike a dialogic centrist note. The syncretic dramaturgy Agboluaje uses in them is not necessarily an act of postcolonial appropriation or postmodern posturing, his style and plays are his responses to the artistic and historical necessities to stage his readings of postcolonial, postmodern, and diaspora realities as he sees them.

Dr Victor I. Ukaegbu

Associate Professor, Theatre and Performance

Department of Media, English, Cultural Studies & Performance

School of The Arts, The University of Northampton

Associate Editor, African Performance Review General Secretary, African Theatre Association