Читать книгу The Patient - Olive Kobusingye - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE SCARY SEVENTIES

From East and West, From North and South

All voices singing, Arise Makerere

Rise up and rise, High up and high

All voices singing

Arise Makerere

Dr. Lumu’s plan had stipulated that a 600-bed hospital would be constructed in each of the four regional headquarters: Mbale, Gulu, Fort Portal, and Masaka. Another 600-bed hospital was to be built in Kampala to relieve Mulago of congestion, and to allow the national referral hospital to serve its main functions of referral, teaching and research. The Amin presidency heralded uncertainty that escalated rapidly. In 1972, barely a year into the presidency, he expelled all the Asian doctors, creating a huge void in the capacity of the hospital and the medical school, literally overnight. A number of non-Asian senior doctors left shortly after, either in protest of the treatment meted out to their Asian colleagues, or for fear of the escalating violence. The heads of department of Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, and Internal Medicine resigned and left in the same week. Amin’s ministers of health, first Dr. Justin Gesa, and later Henry Kyemba, seemed to have been spinning around Amin’s insanely unpredictable plans and demands that any serious intentions for the construction of the hospitals fell by the wayside. Despite the extreme violence that engulfed all professionals, Amin singled out the doctors and judges for unexpected favors. He gave senior consultants Mercedes Benzes, and other doctors got cars as well. As the self-declared economic war intensified and common commodities disappeared from the market, Amin created a special outlet for doctors in Industrial Area. From here, doctors would be allocated sugar, beer, salt, and rice at very low prices. Most doctors would turn around and sell the items to supplement their meagre incomes. Likewise, Amin had a fuel pump installed in Old Mulago close to the Polio Hostel for the exclusive use of doctors.

***

Military doctors everywhere enjoy respect from the men and women they serve, and in times of peace, recruits to such positions are attracted to the trappings of a military office without the risk of combat. Amin’s army doctors would have been no different. They would have had many privileges that their civilian peers did not have – a furnished house, a car, a food allowance, and access to the army shop where they could buy commodities such as wine and whisky that were not readily available on the market. And for all that, the most they would have had to do was examine recruits, and treat minor ailments at the army clinic. For one such doctor (names withheld) life was not perfect, but he was not complaining. The military coup in January 1971 had not brought any change to his personal circumstances. Then things started to change. First, he was singled out during an officers’ meeting as being the doctor. “Eh. Daktari?” the President had half asked, half stated, as though this was a curiosity. Then he started receiving calls to attend to patients whose injuries were clearly not accidental. Multiple fractures, black eyes, bruises all over the body, even burns. He saw most of these patients only once and never asked what happened to them after his one-off treatment sessions. He had to certify deaths whose causes were evidently unnatural. He was already sleeping poorly and having nightmares when the Commandant called him to his office and notified him that there were going to be executions, and that he would be required to certify that the men to be executed were in good health. Executions! His heart did a somersault and then started racing. He felt sick. He had not become a doctor to do this. Besides, if these men were going to be killed, what did it matter whether they had tuberculosis, gonorrhea, or were in perfect health? And once they were shot, why could the men assigned to do the deed not confirm for themselves that their mission had been accomplished? After all, Ugandans were being killed and buried every day without requiring that a doctor confirm their demise. But he had been in the army long enough to know that you did not question orders. He listened attentively, gave the required salute, and walked out of the Commandant’s office with his stomach churning, and his tongue stuck to the roof of his dry mouth. A few years previously, an army officer that he knew well had been executed in Mbale. He had been tried by an army tribunal and found guilty of being a FRONASA8 collaborator. Masaba had been a pleasant guy, and they had played darts together a few times. His execution had left the doctor quite depressed for some time.

***

Kweete was giddy with excitement at the prospect of traveling to Kampala. She had heard her father talk about the city, but she never imagined that she would one day see it with her own eyes. She and her brother Kwesiga, who everybody called Kwesi, often played games in which they were going to Kampala, and coming back with lots of goodies that they imagined were free for the taking once one got to the city. Kweete’s cousin Karungi had been to Kampala. She traveled with her mother to her sister’s wedding, at which she was a bridesmaid. When she returned, Kweete and Biitu were waiting to hear all about the city. They were disappointed. Karungi told them that they stayed in a place called Bukoto, and that her aunt’s house was a flat. That was confusing – how was a house flat? Then the wedding happened at a big church, and the reception was at a big hotel near the church. Biitu wanted to know if she saw the President’s house. She had not. Did she see the TV house? No. Did she see Lake Victoria? No. Biitu quickly concluded that Karungi’s Kampala visit did not count. Now Kweete was about to go there, and she intended to make her visit count.

Kweete had been to Kisizi Hopsital for her routine review, and the Mzungu doctor who examined her talked to her father at length afterwards. Kweete did not understand most of what was said as the white man’s speech was hard to follow, but from what she could piece together, the doctors at Mulago Hospital in Kampala had come up with new ways of treating heart diseases such as she had. Kweete had waited for them to leave the hospital, but on the way home she could not contain her curiosity any longer.

“Father, what did the Mzungu say?”

“He thinks you are doing well. He has said that you should carry on with the medicines that you have been taking.”

“Is that all?”

“He mentioned that there is a group of doctors in Mulago who are working very hard to find better ways of treating heart diseases. He thought it might be good idea for them to examine you as well.”

“So are we going there?”

“Not right away. I need to discuss it with your mother, and to take leave from work to be able to take you. The doctor said it is not urgent, but if and when we do decide to go he will give us a letter to the doctors in Mulago.”

Kweete had to be content with that, not knowing if they would ever go. That had been months ago. Then one night her father came home and announced that he and Kweete would be traveling to Kampala in the morning. He had the letter from the hospital, and as it happened, the hospital van was due to pick up supplies from Kampala, so they had offered to take them to Mulago on the same trip. Everything happened so fast. Kweete had no opportunity to tell her friends that she was going to Kampala. They would be so envious! Only Kwesi was there to wish he was going.

The Medical Outpatient Clinics at Mulago were located on the 4th floor of the hospital’s front wing. There was a pharmacy at the entrance, and there were labs on site to do most of the basic tests needed by the doctors. Patients who did not need imaging could come in for care and leave without needing to get farther into the hospital. All the consultation rooms were designed with wide glass windows overlooking the car park, and the sun and fresh air made this a pleasant place to work, even considering that it was a hospital. Sr. Imelda Atim kept a very orderly clinic. Dr. Kibukamusoke liked to know as soon as he came in how many patients were booked, and if they had the latest lab results on file. He usually saw the new patients first, especially if they were referrals from upcountry. The child from Kabale was the first in line.

Eight o’clock came and went, as did 9 o’clock. This was unusual for Dr. Kibukamusoke to not be at the clinic on time, and more unusual still that he had not communicated about his absence. On the few occasions when he was unable to run the clinic, he let the staff know who would see his patients. At 9.30 am Atim called the doctor’s office, and the telephone went unanswered. Atim walked to the Department of Medicine on the same floor and asked the Department secretary if she had seen Dr. Kibukamusoke. “No. I have not seen him this morning. You may want to check with Dr. D’Arbela in case he is teaching somewhere.”

“He would have let us know. And I noticed his car is not at its usual spot. It seems like he has not come to the hospital at all. Could you please check if someone else has been assigned to see the patients? We have a full clinic.”

It had been only three months since Kibukamusoke took over the headship of the department from Dr. Bill Parson who left in December 1972. By the following day, rumour had it that Dr. Kibukamusoke had left the country. Within a few weeks he was replaced by Dr. Paul D’Arbela, a physician with specialization in diseases of the heart, and one that had made major contributions to the training of specialist doctors at Makerere.

Kibukamusoke’s departure was by no means unique. Some doctors walked off ward rounds to go to the bathroom, and did not return for decades, if ever. The less lucky were picked up by the State Research Bureau agents, never to be seen again. Dr. D’Arbela’s succeeding Kibukamusoke as department head was the easy part. The more difficult assignment proved to be that of personal physician to the Head of State, Field Marshal Idi Amin Dada. Very early on in that role, D’Arbela found out that his predecessor’s woes had stemmed from his attempt to monitor and treat the President’s gout problems. The repeated requests for urine samples worried Amin. He feared that he was being poisoned through the urine. Too paranoid to place his health in the hands of one doctor, Amin had secured the services of an Egyptian doctor on the side. With this knowledge, D’Arbela played it very safe. He made all his prescriptions sound like mere suggestions, knowing that Amin would discuss them with the Egyptian physician, who would very likely issue the same instructions D’Arbela would have given. With this delicate triangular relationship between suspicious patient, cautious doctor, and trusted expatriate back-up, D’Arbela was able to survive Amin’s presidency. His unceremonious exit would come later through a different avenue. For the moment, his biggest preoccupation, and that of his senior colleagues, was how to maintain and even expand the teaching and medical services despite the continuing exodus of highly trained staff.

“Kibukamusoke had taken over as acting Department Head from Bill Parson who left in the first wave of departures after Amin expelled the Asians,” D’Arbela recalled. “When Kibukamusoke left, I was asked to head the department. The Master of Medicine program had been started in 1968 under Parson, and we had to sustain it. Olweny and Kiire were among the first batch from that program. I quickly assigned the promising young doctors to various specialties – Otim to endocrinology, Batambuze to cardiology, there was Mugerwa, Kiwanuka … We ensured that there was succession and continuity of the programs. It was the Masters of Medicine programs that saved the medical school from collapse.”

Drs. Krishna Somers and Paul D’Arbela conducted most of the original research on endomyocardial fibrosis, a disease of obscure cause, which leads to heart failure in the extreme. When the New Mulago opened in 1962, the medical school received a £10,000 grant (equivalent to £160,000 [UGX881 million] in September 2019) from the National and Grindlays Bank in Kampala. With this, they bought equipment for the heart laboratory.9

***

If the hospital suffered a shortage of doctors, the Medical School was probably even more acutely affected. The biomedical sciences of anatomy, physiology and biochemistry were practically depleted of senior staff. Lab technicians were in some instances taking on the roles of the teaching staff. Anthony Gakwaya, an undergraduate in the early seventies, recalled that the class spent almost a year in the biochemistry class discussing the DNA structure which had been discovered by James Watson and Francis Crick some twenty years earlier. Gene sequencing was still very topical, and Frederick Sanger and others were still racing to see who would be the first to discover a method of rapidly ordering – sequencing – the building blocks of proteins. Ugandan medical students were facing an uncertain future with few teachers and hardly any lab reagents, but they were doing what they could to stay in the mainstream of knowledge. The Albert Cook Library that had enjoyed great prestige, and that had subscriptions to a wide variety of scientific journals, could no longer keep up. First there was a slowing down, then the deliveries stopped altogether.

In a span of a few years, student life at Makerere changed from one of relative luxury to one of great hardship. Where the halls of residence had been the envy of even the working class around Kampala, now they were often plunged in darkness from frequent power outages, and water was erratic. Food quality suffered, and was the cause of a few strikes in the early Amin years, before it became evident that the problems facing the nation were far graver than poorly cooked meals. Military presence on Makerere campus became commonplace, and the insecurity that had engulfed the rest of the city now extended to the hill that prided itself in being the seat of independent thinking and academia. The stage was set for a violent confrontation.

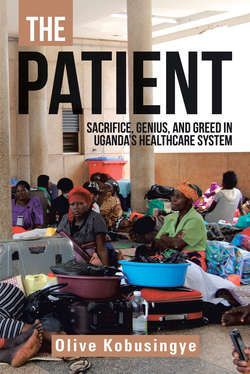

President Idi Amin Dada visits Mulago Hospital at its

10th Anniversary, 16 October 1972. DS Archives

***

On the night of 27 June 1976, Dr. Adam Kimala, Provincial Medical Officer for North Buganda Province, was driving from Mityana to Lugazi when he ran into a big military convoy at Kibuye. He gave the convoy a wide berth and continued his journey undisturbed. The following day he learnt that an Air France plane had been hijacked and landed at Entebbe, and he thought that might explain the military presence on Entebbe road. As the situation evolved, most of the hostages were released, except for some 106 passengers who were either Israelis, or non-Israeli Jews. The hijackers were trading their lives for the release of terrorists held in prisons mostly in Israel, but also in some European countries. All this remained remote to Kimala, whose responsibilities as both the provincial head of the medical services and the Medical Superintendent of Kawolo Hospital kept him busy enough. But fate was about to hand Kimala a strange assignment.

As he recounted, “One morning that week, a Police detective from Lugazi called me to say that they had found a dead body, and I was required to go and do a postmortem. The body was in a sugar plantation in Namawojjolo along Jinja Road. When we got to the body, I examined it, and noted that it was burnt. There was a burn in some sort of straight line from the head to the legs, a pattern unlikely in a live person who would be struggling, suggesting that the burn was inflicted after death. I could see that it was a short white female, probably in her sixties or seventies. I quickly came to the conclusion that this was not a simple murder, and that someone had killed the woman and wanted to hide her identity, or the mode of her death, probably both. Given the circumstances, I thought it best to not make a detailed report. Something told me this body was going to cause us problems. It was dangerous. I wrote a very short report, and said the body was burnt beyond recognition. We sent for prisoners from Lugazi prison and they buried the body right there in the plantation. I gave the Police officer the short report, and went back to the hospital, hoping that was the end of the matter.”

It was not. In a day or so, news broke that one of the hostages, Dora Bloch, had been killed, and that her body had been dumped in Namanve. Kimala began to worry in earnest. He consoled himself that he had not been near Namanve. He prayed that the Police detective and the prisoners would keep their mouths shut. He did not have to wait for long to discover that people could not keep secrets. A few mornings after the postmortem, Kimala was walking to one of the wards when security officers came into the hospital. They asked him for the Medical Superintendent’s office. “I pointed them to my office. As they headed there, I got into the car, and drove to Bugerere. I told my staff that I had to supervise work in the Province - Kyaggwe, Bulemeezi, and Mubende. Three times, the security officers came to my office and did not find me. They searched my office. They went to my home and asked my wife if she knew of my whereabouts. They wanted to know if I had brought any reports home recently. She knew what they were after. She told them that she had heard me talking of a report that I had deposited at the Police. They went straight there and they were given the report. One of them returned and told my wife to let me know that everything was okay, that I had given a good report. After that they never came back.”

***

The date for the execution was set as 9 September 1977. The men to be executed had been tried by an army tribunal and found guilty of various crimes, including plotting to overthrow the government of President Idi Amin, being economic saboteurs, and spying. The program was quite elaborate. The government radio station had aired announcements of the planned executions, and the public was invited to come and witness how enemies of the state were punished. On D-day the prisoners were brought to the Kampala Clock Tower grounds in the Prisons Department vans. They were blindfolded and frog-marched, each to a metallic pole set up for the purpose, where they were tied. An army officer moved from pole to pole ascertaining that they were all properly secured. The soldiers to execute the prisoners lined up with their guns at the ready. The army chaplain was then invited to come and give the men their final benediction, or whatever spiritual comfort he could impart in the grim circumstances. At exactly 4 o’clock the officer in charge of the execution gave the single command to fire, and the shots were discharged, each prisoner stopping three shots directed to the head. After that the doctor, who had been in attendance from the beginning, came forward to confirm that the men were indeed dead. He had been so anguished by having to participate in the executions that he did not think through exactly how he was going to confirm the deaths of the men, shot at close range only moments before. As he approached the poles he suddenly realized he had no tools, and in the same moment realized the absurdity of the very thought of tools. One of the bodies was all but decapitated. He moved along the line barely touching the bodies, although it occurred to him that he could perhaps try to feel for their carotid pulses. He was relieved that the men assigned to remove the bodies were following quickly in his wake, cutting the lifeless bodies off the poles, and placing them in coffins. He did not recall how he left the Clock Tower grounds. He did not recall who he talked to, if anyone. He somehow managed to make it back to his house in Makindye where he downed one Uganda waragi glass after another until he passed out on his living room floor.

***

In 1979 when Amin’s government fell, Kimala was back in Mulago training to be a surgeon. The Israeli government requested Uganda to help locate Dora Bloch’s remains. Kimala led the team that located and exhumed the body. “I could remember where the body was buried. We dug up the bones. Benjamin Bloch, Dora’s son, had brought with him her medical records to help with the identification. Based on some documented dental work, and an implant in her vertebra, we were able to make a positive identification. It was a somber moment, but the son appreciated that we were able to find his mother’s remains. He took them and she was given a proper burial back home in Israel.”