Читать книгу Feed the World: Birhan Woldu and Live Aid - Oliver Harvey - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеBIRHAN WOLDU STARED with wonder at the teeming mass of humanity stretching as far as her eyes could see. From her position high in the wings of the huge Live 8 stage the people seemed all jumbled together on the cropped grass of Hyde Park. Just their little heads and raised, spindly limbs were showing. It made her think of the writhing nests of termites she had seen back home in Ethiopia. There was just enough breeze for flags to flutter in the muggy heat of a London summer’s day – St George Crosses, Welsh dragons, a Red Hand of Ulster, several in the colours of the rainbow. Banners read: ‘Wow Bob, it’s huge’, ‘Hello World’ and ‘Live 8 before it’s too late’. The words of the celebrated Indian human rights activist Mahatma Gandhi flashed up on giant video screens. ‘First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.’ Outside the park, London’s streets were largely empty. Most people were at home watching the ‘Greatest Show on Earth’ on TV. It was the topic of conversation in every pub and every taxi driver had his or her view.

Birhan surveyed the crowd with all the noble and proud bearing of her people who came from the mountains of Tigray Province. Her hair was styled in the traditional way. Plaited into neat cornrows on her crown, it flared out, luxuriantly bouncing on her shoulders. She wore a simple white tunic embroidered with small, light blue Christian crosses. Wrapped around the 24-year-old’s shoulders was a bright white shamma linen shawl stitched here and there with red, blue and green diamonds. Her brown eyes sparkled with life; her clear skin was the rich colour of Ethiopian coffee. Like many from her region, she had a little scar etched on her forehead in the shape of a crucifix. She stood now, like an Ethiopian princess, on a 2 metre- (6.56 feet) wide platform by the side of the huge stage. Bundles of cables ran everywhere like creeping vines. Stacks of guitars stood on castors and a huge silver drum kit was being assembled by frantic roadies.

Just 48 hours earlier, Birhan had been in her family’s stonewalled, corrugated iron-roofed cottage in the remote Ethiopian Highlands. Their cow was tethered to an olive tree outside and bantam chickens pecked the tinder-dry dark brown soil. When Birhan was younger she had slept on stiff ox skins in a dung-walled hut with a thatched roof in a lonely mountain valley. Alone with her goats on the high alpine meadows for the daylight hours, the crust of bread she brought from home often would not be enough to stave off hunger. She would lie down beneath the nanny goats’ back legs and suckle warm milk straight from their teats.

London was a different world. The roaring traffic never seemed to stop and the red buses of the British capital were huge. Amazing food, more than Birhan could ever have imagined, piled high in front of her. After trying hamburgers for the first time, she had now eaten two in as many days. Then there were the people, rushing, always rushing. Why didn’t they say ‘hello’ when they passed each other in the street? It would be rude to walk past people in Tigray without greeting them first. She was glad to have her friend from home, Bisrat Mesfin, with her at this huge concert. She knew that her English wasn’t always good and Bisrat was much more confident when dealing with the farenjis (foreigners). His girlfriend, Rahel Haile Selassie, had also come along to keep them company.

All afternoon the wide-eyed Ethiopians had watched the parade of rock stars trooping past in their lovely clothes. Bisrat had pointed out an older farenji called ‘Paul’ whom he said had once been in a band called The Beatles. Birhan had never heard of him nor of his group. Earlier Paul (Sir Paul McCartney) had played The Beatles’ iconic song ‘Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band’ along with rock band U2. ‘It was twenty years ago today…’, they sang, setting the right note for the day. As Paul squeezed past the throng of supermodels and film stars, U2 released a cloud of 200 white doves which soared high over the crowd as the band roared into its hit ‘Beautiful Day’.

Singer Bono then paused, saying: ‘This is our time. This is our chance to stand up for what’s right. We’re not looking for charity, we’re looking for justice. We can’t fix every problem, but the ones we can fix, we must.’

The crowd seemed so happy; everyone was dancing. Birhan was led to a green Portakabin where a pretty woman with dyed red hair put blusher and eyeshadow on her face. It was the first time she had ever worn make-up and she liked the way it looked so much that she thought she must remember to take some back to Ethiopia with her.

She didn’t know much pop music, preferring the traditional Arabian-tinged music of her homeland. Madonna was the only name on the bill that Birhan recognized before arriving in Britain. Birhan was awestruck.

Now, in a pale linen Nehru suit, his straggly hair tucked under a baggy black cap, musician Bob Geldof came up and hugged Birhan tight, before saying: ‘Ok, darling, this is it. You’ll be fine.’ Standing in the stage wings, Geldof, his dark brown eyes aflame with emotion, seemed tense. Birhan smiled. She appeared as serene and calm as ever. Geldof swallowed hard.

To a deafening roar from the 205,000 crowd, Geldof strode to the centre of the vast Live 8 stage. The Father of both Band Aid and of Live Aid 20 years earlier had, it seemed, done the unthinkable again. It was July 2, 2005, and he had managed to focus the world’s attention once again on the plight of Africa by amassing almost every leading musician who had picked up a guitar in the last 40 years. There stood Sir Paul, a re-formed Pink Floyd, The Who, U2, Sir Elton John, Madonna, Coldplay, Mariah Carey, Sting and George Michael. In 1985 the concerts had been held in London’s Wembley Stadium and Philadelphia’s John F. Kennedy Stadium. Today there were other Live 8s taking place in Toronto, Tokyo, Johannesburg, Paris, Rome, Berlin and Moscow, and once again, in Philadelphia. Then, with an estimated three billion eyes on him from every corner of the globe – and the G8 leaders of the world’s richest and most powerful nations about to meet on British soil – Geldof stopped the music. He had something to say.

‘Some of you were here 20 years ago. Some of you were not even born. I want to show you why we started this long, long walk to justice. It began … because many of us around the world watching here now saw something happening that was so grotesque in this world of plenty. We felt physically sick that anyone should die of want and decided we were going to change that. I want to show you, just in case you forgot, why we did this. Just watch this film.’

With a wave of his hand Geldof motioned to the massive video screen behind him. US band The Cars’ haunting track ‘Drive’, with its melancholy keyboard refrain, echoed through the massive PA system. ‘Who’s gonna tell you when it’s too late, who’s gonna tell you things aren’t so great…’ A stark film of Ethiopia’s almost-biblical famine, when an estimated one million Tigrayan farmers perished of starvation, began to play. It was the same footage shot by a CBC news crew that had been shown at the original Live Aid concert two decades before.

An emaciated little boy, his legs mere bone and twitching sinew, kept trying to get to his feet in the early morning Tigray mist. Again and again. Then he slumped down, defeated. There was no strength left in his hunger-wracked body. Another skeletal boy stared blankly at the camera before burying his face in his bony hands. More and more children followed in a ghastly parade of the dead and dying. Then for a few moments the camera lingered on the tortured face of a little girl. Her desperate father had carried her to a clinic as she fought for life, but a nurse had told him it was hopeless. She gave the child just 15 minutes to live. The little girl’s sunken brown eyes were lifeless behind half-closed lids. Her sallow parchment skin pulled taut against protruding cheekbones. Her swollen lips parted as she apparently took her last breath. Then the film stopped – the child’s ghostly face in 10 metre- (32.8 feet) high freeze-frame above the now silent thousands.

At Live Aid on July 13, 1985, the same video had stopped the world. Twenty years later it had the same effect. TV cameras panning along the ranks of pop fans in their white ‘Make Poverty History’ wristbands picked up the unrestrained grief. Tears flowed and arms were flung around strangers. Now Geldof, his voice croaky with emotion, motioned up at the Ethiopian child’s agonized face and spoke again.

‘See this little girl – she had minutes to live 20 years ago. And because we did a concert in this city and Philadelphia, last week she did her agricultural exams at the school she goes to in the northern Ethiopian Highlands. She’s here tonight this little girl. Birhan. Don’t let them tell us that this doesn’t work.’

Suddenly there she was on the Live 8 stage. She was alive.

Birhan, with Bisrat in her wake, walked over to Geldof and kissed him on the lips. Dignified and radiating an inner calm, the young woman’s jubilant smile flashed around the globe by TV satellite in an instant. The thousands watching in Hyde Park were stunned into disbelieving silence. More tears were now wiped away. It seemed inconceivable that any of those children in that film, their bodies so grotesquely malformed by hunger, could have survived. The little girl who had come back from the dead took the microphone as billions watched on television on every continent and in every corner of Earth.

Slowly, in the rich tones of her native Tigrinya language, she said: ‘Hello from Africa. We Africans love you very much. It’s a great honour to be here and stand on the Live 8 stage. We love you very much. Thank you.’ Bisrat translated her words into English as the crowd roared its approval.

They were a few simple words but enough to grab the world’s attention. Her mere presence said more than a multitude of slogans and worthy speeches ever could. Birhan was living proof that aid worked. That the millions who had bought Band Aid’s ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ charity record and who had thrown loose change into rattled tins and buckets hadn’t done so in vain. Countless Birhans had been saved thanks to Live Aid and numerous other aid initiatives. This beautiful, intelligent woman was now brimming with potential, her dream to become a nurse, like those who gently cradled her as she lay close to death during Ethiopia’s Great Famine of 1984.

From the giant Hyde Park PA system Geldof’s voice boomed out once again: ‘Don’t let them tell you this stuff doesn’t work. It works – you work – very well indeed.’

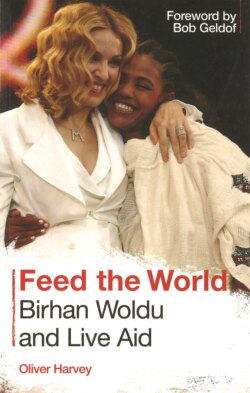

As he uttered the words ‘from one immensely strong woman to another’, Madonna bounded on stage. In a crisp figure-hugging white waistcoat and flowing white trousers, she sashayed over to Birhan and kissed her gently on the lips. The Queen of Pop, a diamond-encrusted ‘M’ dangling from her neck, was visibly overcome with emotion. Pausing momentarily to compose herself, her alabaster-white hand clasped Birhan’s sinuous brown arm and raised it skywards. With that gesture the two women acknowledged the triumph of human spirit, the uniting of the First World and the Third.

Madonna carried on clutching Birhan’s hand as she launched into her hit ‘Like a Prayer’.

‘Are you ready, London, to start a revolution? To change history?’ Madonna demanded.

Bisrat, proudly wearing the T-shirt emblazoned with the name of the African Children’s Educational Trust (A-CET) charity that he helps run, danced along, all the time feeling like this was a dream.

As Madonna started her second song, ‘Ray of Light’, Birhan and Bisrat walked back to where I was waiting for them in the stage wings; their elation shone brightly in their faces. Birhan was transfixed as she watched Madonna sing: ‘Faster than the speeding light she’s flying, trying to remember where it all began…’ Bisrat explained that this was a perfect song for his friend. Birhan meant ‘light’ in their language.

My newspaper, The Sun, had flown Birhan almost 6,000 km (3,700 miles) from Ethiopia for the concert. It had been a roller coaster 10 months since she and I had first met. What had started as an interview with Birhan at her Tigray home as part of a series on the 20th anniversary of Ethiopia’s famine had mushroomed into something incredible.

There had been the emotional meeting with then British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Geldof in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa. This in turn led to the re-recording of the Band Aid single ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ The impetus from the song was a factor in pushing an initially unenthusiastic Geldof to get behind a concert on the anniversary of Live Aid. Since then Birhan, Bisrat and I had become good friends.

As they emerged from the glare of billions, the relief was huge. We hugged in disbelief, our eyes prickling as the tears welled. When Birhan had enthusiastically agreed to appear at the concert she couldn’t possibly have imagined the scale of the occasion. She said she wanted to do it because she knew what it was like to be starving hungry and didn’t want other African children to suffer like she had done. Her composure and grace had been astonishing and humbling. Despite outward appearances, she admitted her heart had been fluttering as she waited backstage with all the pop stars. The devout Ethiopian Orthodox Christian had put herself in the hands of the Lord as she had throughout her tumultuous life. With the eyes of the world on her, she had found strength.

‘I thought of the years of suffering my family and my country had endured,’ Birhan explained. ‘I wanted to show the world we Ethiopians are a proud and strong people. I wanted my father, Woldu, to be proud after all the sacrifices he had made for me.’ Birhan explained that Woldu had always told her that God had spared them from the famine for a reason. ‘I think today was the reason,’ she said solemnly. An elated Geldof, hugging his partner, the French actress Jeanne Marine, added: ‘Birhan’s story is what this whole thing is about.’

If Live Aid was about charity then Live 8 was about justice, the organizers said. The brutal fact was that two decades on from Live Aid 50,000 people – 30,000 in Africa alone – were still dying each day from easily preventable diseases. It was true that Live Aid had raised over US $100 million – by far the most a charity has made in a single event – and had almost doubled that through subsequent sales and merchandizing. It was an astonishing achievement but it didn’t solve Africa’s woes. Band Aid had been a plaster but it didn’t go to the root causes of what had kept Africa hungry and sick.

Geldof had subsequently immersed himself in development theory after Live Aid. He found the aid business was far from simple. He was staggered to learn that Live Aid’s US $100 million was the amount poor nations had to pay back to Western nations in debt repayments every three or four days. For decades, poor countries spent more money repaying old debts than they did on health and education combined. Most of the billions had been accumulated under corrupt regimes during the Cold War and had accrued more and more interest. Trade rules and tariffs and taxes have also kept Africa poor. The apparently generous West was doing very well from the impoverished undeveloped world. A stark statistic quoted in 2005 was that for every US $1 given by rich nations in aid, US $2 was taken back in unfair trade.

The leaders of the G8 club of the wealthiest nations on Earth were due to meet at the luxury Scottish hotel Gleneagles in four days time. Geldof summed up Live 8 by saying that the world had spoken. He had a mandate and the political demands were 100 percent debt cancellation for the world’s poorest nations, fairer trade laws and doubling the levels of aid to US $50 billion a year in return for better governance. He hoped that Birhan had shown the politicians how much the world lost every time a child dies.

The world’s most powerful man had been watching the pop concert. US President George W. Bush later told Geldof in a private meeting: ‘The most moving moment was when Birhan, the child who had appeared at death’s door in a film at the Live Aid concert in 1985, came out.’ Geldof was clear about the importance that Birhan’s show-stealing appearance at Live 8 had on Bush. ‘It clearly reminded him that when politicians negotiate in the rarefied atmosphere of a place like Gleneagles, there are individuals like her who live and die by their decisions.’

Now Birhan joined her friend Rahel to sip fruit cocktails in the backstage hospitality area at Live 8. Later she would allow herself a glass of red wine.

In the VIP zone free lobster and wine were served, but Birhan preferred her new favourite dish, a burger and chips. She had spent the earlier part of the day backstage, unknown and largely ignored by the great and the good. Now she was the centre of a social whirl.

Ex-Manchester United star David Beckham came over to greet Birhan, with his wife Victoria. They posed for pictures with her. Beckham looked positively delighted. ‘I’ve heard about you Birhan and I think it’s wonderful you are here today.’ Bisrat, then a United fan, found it difficult to contain his glee. ‘Thank you Mr David, sir.’ A photograph of that time has pride of place in Bisrat’s home in Mekele even though he has since switched his allegiance to Arsenal.

Then Hollywood star Brad Pitt came over. Bisrat had to explain to Birhan who the blond-haired farenji was. The actor told Birhan that she was ‘a very special person’. Later she would comment that he had very kind eyes. Billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates and UN Secretary General Kofi Annan strolled past, as did Sir Paul McCartney with wife Heather Mills, capturing the day on a video recorder. They were no more recognizable to Birhan than the other farenjis in the crowd at the front of the stage.

Suddenly Birhan’s eyes widened and she began giggling with excitement. She had finally recognized a face among the celebrity-studded crowd. It was Jeremy Clarkson, the comparatively less glamorous presenter of BBC motor show Top Gear. The programme is shown abroad on BBC World and is a favourite with Ethiopians. A large glass of rosé in hand, Clarkson was happy to pose for pictures. Later, Birhan, Bisrat and Rahel were back on the little 2 metre- (6.56 feet) wide gantry to watch The Who and a re-formed Pink Floyd play for the first time in over 20 years under the slogan: ‘No More Excuses’.

Bear-like concert promoter Harvey Goldsmith, a giant wall clock dangling around his neck, barked orders out at the pop stars, who shuffled around backstage as if they were errant schoolchildren. Then, Sir Paul McCartney was back on stage to lead a mass singalong to The Beatles’ hit ‘Hey Jude’ with the artists who had performed and the rapturous crowd.

Birhan stood swaying along to the music, smiling softly to herself as she watched transfixed. It had been a special day, one so different from her normal life.

Then it was over – Live 8 had pulled off what Live Aid had achieved 20 years before. Cynicism had been banished at least for one day, it seemed.

Leaving on foot through throngs of euphoric pop fans to head back to their Mayfair hotel, the three Ethiopians nattered away about what they had seen and heard. Some people in the crowd recognized Birhan. Politely smiling, most nodded ‘hello’ at her and kept walking. Others shook her hand with excitement.

The next morning over breakfast, Birhan was more talkative than usual. She had been unable to sleep in the strange, crisp white hotel sheets and had lain awake thinking of home. Of her beloved mountains of Tigray where that morning her father Woldu would wake with the rising sun to harness his lyre-horned plough oxen.

She loved the excitement of London, riding on the tube and seeing the people from all over the world – and the burgers, of course. She knew there were money and jobs here and good hospitals and great universities. But she wanted to go back home. Live 8 had helped Birhan understand her life, she explained to me. She now realized how the spirit of Live Aid had galvanized Western goodwill all those years ago and exactly what her part in it had meant. She finally understood why the farenji TV crews and reporters had wanted to talk to her.

Birhan had always found it difficult to speak about the famine days of the 1980s. She had been very young, it was true, but perhaps she had also blocked out the true horror of what had happened out of necessity. Her mother, Alemetsehay, and five-year-old sister, Azmera, had perished in the Great Hunger after all. Now Birhan began to talk as she hadn’t been able to before. She told of how she’d wept as her father spoke of what she called the ‘hunger time’; how the men with guns had come for their family and pushed them like cattle onto an old Russian plane, stealing them away to a resettlement camp in the Ethiopian Lowlands, around 1,300km (800 miles) away from their home. She spoke of how her father had told them that they would walk home, even though they were penniless and starving. That he would carry Birhan and her little sister on his shoulders all the way back to their ancestral mountains. To Tigray. To home.

She began to tell her family’s story, of her father’s struggle, of the epic journey to life.