Читать книгу Feed the World: Birhan Woldu and Live Aid - Oliver Harvey - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAUTHOR PREFACE

IT’S A MERE SEVEN-and-three-quarter-hour night flight from London to Ethiopia over the bumpy heat thermals of the Sahara. You land in a nation literally out of time. Setting off from a cloudy Heathrow in 2011 you touch down in capital Addis Ababa’s gleaming and impressive Bole airport in 2004. Ethiopia has never switched from the Julian calendar like Europe did in 1582 and so is permanently seven years and eight months behind. You might even have landed in Ethiopia’s extra month. It gives rise to the tourist board’s boast of ‘13 months of sunshine’. The clock on the wall is confusing too. There is a 12-hour day, beginning at dawn and ending at sunset.

Ethiopia is a land apart. Tourists expecting a country of barren desert are confronted by soaring peaks, lush river valleys and reed-fringed lakes. It has been called the ‘Cradle of Humanity’, where modern humans first evolved. It is the world’s second oldest Christian country and was never properly colonized in the Scramble for Africa. It has an ancient written language Ge’ez; there are medieval stone castles in Gonder and rock-hewn churches in the holy city of Lalibela, often described as the ‘eighth wonder of the world’. The fiercely proud and profoundly religious people can look as Arabian as African.

A further hour-and-half flight from Addis brings you to Mekele in Ethiopia’s mountainous north – this is the home town of Birhan Woldu. Mekele, capital of Tigray Province, is now a thriving city of over 200,000. Visible on the horizon are giant white wind turbines, which are being constructed above fields tilled by oxen-dragged wooden ploughs, a method unchanged since the Iron Age. Cement and tile factories line the Chinese-built highway. Camel trains, laden with salt blocks cut in the distant Danakil Depression, plod towards the city’s market past expensive villas with satellite dishes bolted to their walls for their expat owners to catch the latest game while on vacation from London, Toronto and Seattle. In 1984 the tinder-dry plains around the city were the epicentre of the 20th century’s worst humanitarian disaster. A ‘biblical famine’ in which an estimated one million people died. It could have been far more – nobody really knows for sure. Like thousands of others, Birhan and her family came here seeking salvation when their crops shrivelled in the sun and their grain stores emptied.

I have a dear friend, Anthony Mitchell, to thank both for introducing me to this amazing land and for helping me find the path to Birhan and her family. A former foot-in-the-door hack at Britain’s Daily Express newspaper, Anthony had moved to Addis to be with his future wife, Catherine Fitzgibbon, who worked for Irish charity Goal and later Save the Children. In 2001 Anthony and I enjoyed a Boy’s Own adventure, trekking and camping in the breathtakingly beautiful Simien Mountains. We hired a cook, a guide and a AK-47-toting guard while our mules were laden with wine and whisky, blankets and fresh food. Passing through the upland villages, it was the warmth, easiness and the sheer joy of living shown by the Ethiopian people that stayed with me.

When I returned to Ethiopia in 2002, to write development features for my newspaper The Sun, the UK’s biggest-selling paper, Anthony was on hand with his by now expert knowledge of the region. In the parched Awash district in central Ethiopia I witnessed for the first time the horrific sight of proud but malnourished families queuing at feeding centres. Ethiopia still couldn’t feed itself nearly 20 years after the famous Live Aid concert.

In the following year Anthony and I were both part of a press pack shadowing Bob Geldof as he criss-crossed the country. Anthony would later be forced out of Ethiopia after the government accused him of ‘hostile’ reporting. He would never leave his beloved Africa, however. Anthony was one of 114 people killed when Kenyan Airways flight KQ507 plunged into a mangrove swamp in Cameroon on May 5, 2007.

In September 2004 though, I had rang Anthony to ask him to help me set up an interview with Birhan Woldu who had been seen close to death in the famous film of starving children screened at Live Aid. The idea was to provide a real human story as part of a series on the 20th anniversary of Ethiopia’s famine that I was writing for The Sun. To move away from dry development facts and convoluted aid arguments and show what one life saved really meant. Then it mushroomed into something incredible and unforeseen. Birhan’s story simply resonated so strongly.

First there had been an emotion-charged meeting arranged by my paper with then British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Bob Geldof who were both in Addis Ababa for a Commission for Africa (CFA) summit. Then The Sun’s Editor, Dominic Mohan, had come up with the idea of re-recording the Band Aid single ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ two decades after its original release. When I suggested it to Geldof, he batted straight back: ‘Only if you fucking organize it.’

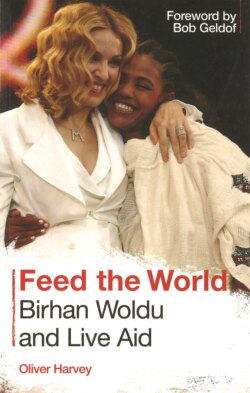

The Sun subsequently flew Birhan to London for the recording in November 2004. Former Beatle Sir Paul McCartney, U2’s Bono and Coldplay’s Chris Martin either sang or played. Birhan’s retelling of her heart-rending story as the symbol of Live Aid helped push the song to Number One in the British charts and raised £3 million for Africa. It was also a factor in pushing Geldof and others to organize the ‘Greatest Show on Earth’, the Live 8 concerts in 2005.

I was with Birhan and her friend and mentor Bisrat throughout the Band Aid re-recording and Live 8. They both became good friends. Birhan was born in a mud-walled hut into a subsistence-farming world that had changed little in millennia. The glitzy pop world was naturally an acute culture shock to her. With all the pride and dignity of her people, she remained wonderfully unaffected by all the razzmatazz. Slowly Birhan’s confidence grew. Over time she began to confide the horrors of her early life and the joys that would later come. Our families met and became friends. In 2007 I took my mother, Sue, on holiday to Tigray to meet Birhan’s family. My late mum, who owned a smallholding in Devon, spent hours discussing the finer points of cattle rearing with Woldu. In December 2009, Birhan asked me if I would write her life story for The Sun. When I suggested it would be better served as a book, she readily agreed. All author’s profits will be split equally between Birhan and the charity that supported her, the African Children’s Educational Trust (A-CET).

During the long hours of interviews and research in Ethiopia for this book, Birhan and her father Woldu have been incredibly generous with their time and hospitality. Both discussed family bereavements and harrowing events that they had sometimes not spoken about since the days of the famine. They always remained cheery and unfailing hosts. There was an endless stream of the world’s best coffee and Woldu always made sure he sent me home with a huge pot of wonderful Tigrayan honey. I was also privileged enough to spend an Ethiopian Christmas Day at the family home. Birhan’s stepmother, Letebirhan, and sisters, Lemlem and Silas, were also extremely patient and helpful when interviewed. Birhan’s fiancé, Birhanu, was equally welcoming. They remain an amazingly close, extended African family, all completely unchanged by the global attention Birhan has received.

I found out much of the family’s latter good fortune was down to the distinguished Canadian journalist Brian Stewart. His crew from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) had originally filmed Birhan when she was close to death. Brian was a reporter who didn’t forget the horrors he witnessed when he reached the comforts of home. He later returned to Ethiopia and made sure Birhan and her siblings had schooling and the family a decent home. Brian’s flurry of transatlantic emails for this book were astonishing in their detail and candour. Birhan’s story is thus Brian’s too. The family say they owe him everything and a large photograph of Brian has pride of place on Woldu’s eucalyptus-wood chest of drawers. Brian’s former CBC colleague Colin Dean, with him in Ethiopia in 1984, and CBC News Senior Political Correspondent Terry Milewski also provided valuable insight.

The day after I first interviewed Birhan in October 2004, I discovered through both Anthony and expat gossip in Addis that Bob Geldof was travelling in a remote part of western Ethiopia. Thumbing through the Lonely Planet guidebook I found the most likely hotel he would be staying in. The receptionist confirmed that they did indeed have a Mr Geldof staying there who was having a shower after a long day on the road. ‘How the fuck did you find me?’ was Geldof’s startled response when I got hold of him. I waited for him to use another expletive-ridden expression when asked for an interview. Instead, he proceeded to rattle through the Band Aid story, providing reams of headline-grabbing quotes, while barely drawing breath.

When Geldof and Birhan met for the first time just days later it was a special moment for both of them. Live Aid bound them together. Birhan’s vitality and promise encapsulated everything that he had been banging his fist about for 20 years. And Africa keeps calling him back. Travelling in his adored Ethiopia, he is a force to be reckoned with – sometimes tearful at what he witnesses, at other times seething with rage at his inability to get things done quicker. He’s never, ever sanctimonious and his knowledge of the aid business is now extraordinary. It has to be. The media is waiting, licking its lips, for him to slip up. Yet, I believe his mass-mobilization of public support for Africa will see him come to be recognized as one of the most significant public figures of the late 20th century.

Geldof called Birhan the ‘Daughter of Live Aid’ and Birhan loves him, she says, as another father. His wonderful foreword to this book is greatly appreciated.

Snappy-dressing, 30-something famine survivor Bisrat Mesfin and grey-haired former British Army officer David Stables are an unlikely double act, but together they run A-CET, a small charity that provides education for vulnerable Ethiopian children. The results are astonishing: graduates include a doctor, a human rights lawyer, a systems analyst and a human biologist. One A-CET pupil, Sammy Assefa, made it to Britain’s Sangar Institute in Cambridge to carry out vital PhD research into mosquitoes to combat the scourge of malaria. Both Bisrat and David have been astonishing in their support since 2004. Bisrat was at Birhan’s side throughout her journey, which culminated in Live 8. He provided the translation during interviews from Ethiopian languages Tigrinya and Amharic for this book. Although Birhan’s English is now reasonable, for many of our conversations she found it easier to speak in her native Tigrinya.

There is no literal translation from the Tigrinya and Amharic script to English. ‘Mekele’ can be spelt ‘Mek’ele’, ‘Makele’, ‘Makale’, ‘Mekelle’, and so on. I have tried in this book to use the most commonly used form or, for names, the spelling Birhan’s own family prefers. Dates and times have been converted into their Western forms.

My Editors at The Sun, Rebekah Brooks, now Chief Executive of the paper’s parent company News International, and Dominic Mohan, have been incredibly supportive. They have consistently commissioned me to write development features from Somalia to Sierra Leone and many nations in between.

The Sun’s legendary Royal Photographer Arthur Edwards accompanied me to Ethiopia when I first met Birhan and was a constant source of shrewd journalistic advice and ready wit. He also provided some wonderful pictures for the book as did his son Paul, also a Sun photographer. My brother, Giles Harvey, also helped with processing pictures and my partner, Karen Lee, spent many hours transcribing interviews. I’d also like to thanks Sun colleague Sharon Hendry for introducing me to New Holland and my publisher Aruna Vasudevan for her insight and patience as deadlines loomed.

Birhan is desperately proud of her homeland and its unique culture. She wishes Ethiopia was known in the West for more than just famine. Today, she works tirelessly to end poverty and suffering in Ethiopia. Her mother, Alemetsehay, and sister, Azmera, died in the famines of the 1980s. Birhan would like to make sure they, and the countless others who perished in those dark days, are never forgotten.

–Oliver Harvey, Castle Hotel, Mekele, May 2011