Читать книгу Rebellion in Patagonia - Osvaldo Bayer - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеBy Scott Nicholas Nappalos and

Joshua Neuhouser

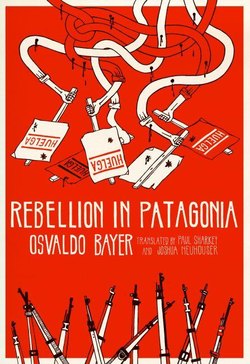

Rebellion in Patagonia is one of the true classics of Latin American social history, both for the clarity of Osvaldo Bayer’s prose as well as for the importance of the events it describes. Here Bayer uncovers the story of the 1920–1922 strike wave by Patagonia’s rural peons, led by a Spanish anarchist named Antonio Soto, and its culmination in a massacre dwarfed only by the disappearances that occurred under the 1976–1983 military junta—but ordered by a democratically elected president. He evokes the heyday of the early-twentieth century anarchist movement, which was truly international: exiled Russian revolutionaries and German World War I veterans make their appearances in these pages, as does a deported organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), who happened to share an apartment with the future secretary of the Peninsular Committee of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI). There are Tolstoyan pacifists who turn to violence; illiterate Chilean peons who commemorate the execution of Francisco Ferrer, the Catalonian founder of the Modern School movement; and a sex strike by Patagonia’s prostitutes.

The reader can jump directly in with little knowledge of South American history—Patagonia is only slightly less alien to the Buenos Aires book-buying public than it is to those of us in the English-speaking world, so most of the required background information already comes included—but some may require more context, especially as the history of Argentina before the Perón era is largely unfamiliar to most North Americans.

The Patagonian rebellion was, in many ways, the culmination of a long series of social struggles that date back to the end of the nineteenth century. Prior to this time, Argentina was an isolated agrarian country with land ownership patterns that had remained largely unchanged since the colonial era, but the growth of global capitalism and the demand for the country’s agricultural products pulled it into the world system, while the influx of immigrants that began in the 1850s brought the latest European social theories with them—including socialism and anarchism.

The first immigrants were skilled laborers who generally arrived for concrete economic reasons, as Argentine society was defined by a degree of economic mobility up until the 1880s. The arrival of French leftists fleeing from the repression of the Paris Commune brought the first organized socialist effort with the founding of a section of the First International, though it had little impact. Anarchists began organizing around 1879 as part of the Bakuninist section of the First International. Notably, Errico Malatesta came to Argentina and helped found some of the earliest resistance societies, which were the form class struggle took in late-nineteenth century/early-twentieth century Argentina. These resistance societies emerged out of the mutual aid organizations that helped new immigrants navigate a country with no real safety net or infrastructure to receive them. They retained the cooperative mutual aid model but united it with collective actions aimed at improving the conditions of the working class. The first unions were formed in urban areas in 1887 and socialist and anarchist publications rapidly proliferated throughout Argentina in the following decade. Rent strikes began around the same time and workers organized against the social ills rampant in the country’s overcrowded and destitute slums, such as addiction, crime, prostitution, and disease.1

The anarchist movement fully asserted itself as a unified working class force in the 1890s with a general strike in the city of Rosario in 1895 and a strike wave in support of an eight-hour workday in Buenos Aires in 1899. In 1901, thirty-five delegates representing some seven thousand resistance societies from across the country came together to found the Argentine Workers’ Federation (FOA), which was based around the principle of autonomy from all political parties. General strikes, boycotts, sabotage, and rent strikes were endorsed as tactics and the new federation resolved to found free libertarian schools and union hiring halls. The federation’s second congress, in 1902, consolidated these anarchist positions, leading the socialists to leave the organization. Out of the federation’s 7,620 resistance societies, only 1,230 left, forming the nucleus of the General Union of Workers (UGT).2 By 1905, the UGT had adopted a form of neutral syndicalism, neither anarchist nor socialist, influenced by France’s General Confederation of Labor (CGT), while the FOA—having changed its name to the Argentine Regional Workers’ Federation (FORA) to make explicit its internationalist orientation and its rejection of nation-states and borders—voted at its fifth congress to adopt anarcho-communism as the ultimate goal of the organization. The FORA pushed for a strict division between revolution and the day-to-day demands made by unions. Its congresses were also extremely progressive for their time, taking up issues such as gender equality, the rights of prisoners, internationalism, and the social causes of disease in urban areas at a time when such positions were rare, especially in the labor movement.

The growth of the labor movement did not go unnoticed by the ruling class. Military intervention became a commonplace measure to repress strikes, but it was clear that the movement was challenging the ability of the state to control it. The government approved the Residency Law in 1902, which gave the government free license to deport foreign activists. Anarchists—many of whom were immigrants—were explicitly targeted by this law and were rounded up, held incommunicado, and summarily deported. This measure was followed by a 1904 labor code that sought to legalize, regulate, and control unions and strikes, some of the first legislation of its kind in the world. It failed in practice, however, because it was rejected by both capital and labor—capital refused any concessions to labor, while labor refused any attempt to restrict its freedom of activity. Six years later, the Argentine government’s repressive powers were further expanded with the Social Defense Law, which provided strict penalties (including prison time) for organizing demonstrations without a permit, publicly using anarchist symbols, coercing others to join a strike or boycott, insulting the Argentine flag, or defending any violation of this law, either verbally or in writing.

The year 1909 proved to be a turning point in the history of Argentina’s anarchist movement. The police chief of Buenos Aires, one Colonel Falcón, ordered the military to open fire on a May Day demonstration, killing somewhere between four and ten workers and wounding many more. This tragedy managed to unite Argentina’s divided working class. Over sixty thousand union members accompanied the funeral procession of the slain workers, while the FORA and the UGT came together to declare a general strike. After one week, the strike managed to force the release of eight hundred imprisoned workers, though it was unable to secure the resignation of Colonel Falcón, who was later assassinated by a little-known FORA member, a Russian immigrant named Simón Radowitzky who had survived the massacre. The joint general strike encouraged Argentina’s unions to move towards unity: in the months following the massacre, the UGT joined together with a group of independent unions to form the Argentine Regional Workers’ Confederation (CORA), although the repression that followed the assassination of Colonel Falcón prevented further unity talks with the FORA from taking place.

As an aside, Radowitzky is one of the most interesting figures in the history of Latin American anarchism: he participated in the Russian Revolution of 1905 as a teenager and fled to Argentina after its defeat. Following his assassination of Colonel Falcón, he was sent to the infamous Ushuaia prison in Tierra del Fuego—known as the Argentine Siberia—where he was tortured and raped by the warden throughout his years of imprisonment. The anarchist movement’s campaign to secure his release from prison was finally successful in 1930, though a nationalist coup later that year forced him to move to Uruguay, where he resumed his organizing work until he was once again imprisoned. After being freed, he moved to Brazil, where he engaged in anti-fascist organizing before going off to fight in the Spanish Civil War. After Franco’s victory in 1939, he fled to France, where he was placed in a concentration camp. He then made his escape, evading the pending Nazi invasion by just under twelve months. That June he settled in Mexico, where he worked in a toy factory until his death in 1956, but he remained active in the anarchist movement and wrote for Mexican anarchist publications.3

The centennial of Argentina’s independence from Spain, celebrated in 1910, was marked by a perhaps inevitable clash between the year’s triumphant nationalism and the restless labor movement. On May 8th—less than a month before the centennial celebrations, scheduled for May 25th—seventy thousand people took to the streets of Buenos Aires to protest the mistreatment of inmates in the National Prison. The CORA and the FORA separately resolved to begin a general strike on May 18th if their demands, including the repeal of the Residency Law, were not met. The government began making arrests on May 13th—in all, over two thousand union members were imprisoned—and a state of emergency was declared the following day. The police organized nationalist gangs to raid union halls, the offices of left-wing newspapers and immigrant-owned businesses. But the strike still went forward. During the centennial celebrations, the trolleys of Buenos Aires could only advance under armed guard and anonymous saboteurs ensured that the electric lights that had been installed to illuminate the city would remain dark.4 “The government won,” FORA organizer and anarchist historian Diego Abad de Santillán would later write. “But history will remember that, to celebrate Argentina’s independence, it was necessary to turn Buenos Aires into a military camp, with a state of siege and overflowing prisons.”5

By 1910—also an election year—it was clear that Argentina’s oligarchy could not continue ruling as it had; things would have to change in order for them to stay as they were. The National Autonomist Party had dominated Argentine politics for the previous thirty years, protecting the interests of Argentina’s commercial and land-owning oligarchy, ensuring domestic stability and moving the country past the civil wars of the nineteenth century. But it was only able to maintain its grip on power through widespread electoral fraud and disenfranchisement—it’s estimated that only 20 percent of the native-born male population voted during the 1910 elections—and by the turn of the century, the party had begun to collapse under the weight of factional infighting.6 The violence seen during the centennial made it clear that the vaunted stability of the so-called Conservative Republic ushered in by the National Autonomist Party could not last without major changes, and so one of incoming president Roque Sáenz Peña’s first actions in office was to pass an electoral reform establishing the secret ballot and compulsory suffrage for all adult male citizens.

Though the intention behind this reform was to provide the ruling oligarchy with democratic legitimacy, the Sáenz Peña Law, as it came to be known, in effect handed the country over to the Radical Civic Union, Argentina’s main opposition party. Formed in the 1890s, when an economic crisis divided Argentina’s oligarchy into competing factions, the Radical Civic Union staged a series of unsuccessful coups at the turn of the century. After its founder, Leandro Alem, committed suicide in 1896, leadership of the party passed into the hands of his nephew Hipólito Yrigoyen, who worked to expand the party’s base beyond the intra-elite struggles of its early years. Following the party’s final coup attempt in 1905, Yrigoyen decided to change his strategy from military conspiracy to grassroots organizing, recruiting urban professionals, small business owners and other middle-class elements to join the Radical Civic Union. Yrigoyen’s populist attacks on the country’s oligarchy appealed to those Argentines who found themselves unable to advance, while local Radical committees organized street corner meetings and free concerts, opened medical clinics, and distributed food to the needy in an attempt to win over the country’s working class. By the time Argentina’s first elections with universal male suffrage were held in 1916, the Radical Civic Union had positioned itself to easily crush the conservatives. The final results were not even close: Yrigoyen was elected by a thirty-three-point margin.

Once in office, Yrigoyen strove to paternalistically present himself as the “father of the poor” by integrating an immigrant workforce into the framework of Argentine nationalism, providing workers with access to credit and a rising standard of living, and expanding the country’s middle class by founding universities and opening up new opportunities in the public sector bureaucracy. His populist reforms sought to shore up support from a battered and militant working class and channel it into institutional change that could cool off an explosive situation, yet without undertaking land reform or altering the basis of Argentina’s export-oriented economy. This political strategy is familiar to us now, but the Radical period in Argentine history occurred many years before similar center-left attempts to co-opt working class radicalism, such as the New Deal in the United States or the Popular Fronts in Western Europe.

During these years, Argentina’s labor organizations continued to advance towards unification. The first unification congress between the FORA and the CORA—much-delayed by state repression—was finally held in December 1912, although the organizations would not merge until September 1914, when the CORA dissolved itself and joined the FORA. But this unity would not last long. During the ninth congress of the FORA, held in April 1915, a resolution was approved that made the labor federation officially non-ideological, thus rejecting the union’s previous anarcho-communist line. “The FORA is an eminently working-class institution, made up of affinity groups organized by trade which nevertheless belong to the most varied ideological and doctrinal tendencies,” the resolution stated. “The FORA therefore cannot declare itself to be partisan or to advocate the adoption of a philosophical system or a determined ideology.”7 The adoption of this resolution provoked a split; the anarchists withdrew from the federation in May of that year and formed the FORA V—after the FORA’s fifth congress, when the resolution in favor of anarcho-communism was adopted—leaving the syndicalists in control of what came to be known as the FORA IX, after the resolution of the ninth congress.

Another difference between the two FORAs had to do with their composition—the FORA V had a strong base in Argentina’s largely immigrant workforce, while members of the FORA IX were overwhelmingly native-born Argentines, with some affiliated unions (such as the Maritime Workers’ Federation) even going so far as to ban immigrants from joining.8 With a reformist orientation and a rank-and-file who were largely eligible voters, building an alliance with the FORA IX became a clear priority for the Radical Civic Union as it sought to win the working-class vote. When Yrigoyen took office in 1916—just one year after the split in the FORA—he adopted a policy of largely giving the FORA IX a free hand while maintaining the fierce repression employed by his predecessors during strikes organized by the FORA V.

The first labor dispute faced by his administration occurred just one month after he took office, when the sailors, stevedores, and boilermen of the Maritime Workers’ Federation (FORA IX) went on strike to demand that their wages be adjusted to the rising cost of living. Yrigoyen invited the union’s leaders to meet with him at the Casa Rosada and promised to refrain from using the police to protect strikebreakers, thus giving the workers the breathing room needed to settle the dispute with their bosses. The strike ended one month later with a victory for the union.9 This would generally set the pattern for future strikes under the Yrigoyen administration—at least for those organized by the syndicalists. Things would be very different for socialist and anarchist-led strikes.

In December 1918, the United Metalworkers Resistance Society (FORA V) declared a strike at the Vasena factory, demanding higher wages, an eight-hour workday and the right to overtime pay. The Vasena family proved to be intransigent; they not only hired strikebreakers but used their connections to the Radical party to obtain the weapons permits needed to arm them. But the metalworkers received the solidarity of the city’s unions and merchants—railway workers refused to unload raw materials destined for the Vasena works, while local shopkeepers donated food, coal, and other necessities to the strikers—and so the strike dragged on for over a month. By the beginning of 1919, there were nearly daily clashes between strikebreakers and the police on one side and strikers and their neighbors on the other. When the police killed four workers on January 7th, rioting and wildcat strikes across Buenos Aires led the FORA V to declare a general strike (the FORA IX declared its solidarity with the dead but declined to stop work). Barricades rapidly went up across the capital and workers sacked grocery stores and distributed goods to the populace. The Vasena works, trolleys, and police vehicles were torched as a clash broke out between the people in arms on one side and the police and nationalist gangs on the other—though these events are often spoken of for the bloodiness of the repression, they also represented a moment in which the Argentine labor movement attempted to assert itself and directly create an anarchist society through popular revolts. The government required a full military mobilization to regain control of the situation and, as the events described in this book show, the political situation would remain volatile for years to come.

Once the army restored order—at the cost of an estimated seven hundred lives—gangs of rich and middle class Argentines organized a pogrom, taking out their anger at the strikers on the Jewish community of Buenos Aires.10 This pogrom—the so-called Tragic Week—also marked the rise of Argentina’s nationalist movement, a proto-fascist political tendency that sought to expel immigrants, end collective bargaining, and overthrow the democratically elected government. On January 15th, 1919, Rear Admiral Manuel Domecq García—who had armed and organized the “civilian volunteers” responsible for the pogrom—announced the formation of the Argentine Patriotic League, whose goal it would be to repress future outbreaks of working class unrest.11 Attracting military officers, policemen, large landowners, and right-wing intellectuals to its cause, the Patriotic League quickly became one of the most prominent nationalist organizations in Argentina and worked hand-in-glove with the police to violently break strikes across Argentina, but most infamously in Buenos Aires, La Palma, La Forestal, Villaguay, Gualuaychú, and Patagonia—where anarchists affiliated with the FORA V led a strike that ended in one of the worst massacres in Latin American history.

Though born in the heat of the immediate postwar political struggles, the nationalist movement would outlast its anarchist and Radical opponents to become the single most important tendency in twentieth-century Argentine politics. During the early years of the movement, anti-Semitic, anti-feminist, and anti-democratic ideas surged in popularity, while Mussolini, Hitler, and Charles Maurras became heroes of the Argentine right. “Let my compatriots—be they Radicals, conservatives or progressive liberals—put their hand in the fire if they did not make Mussolini’s slogan ‘Rome or Moscow’ their own in those years,” wrote the nationalist intellectual Juan Carulla in 1951.12 By 1924, Leopoldo Lugones—Argentina’s greatest modernist writer and once a man of the left—had embraced the far right, calling on Argentina to follow the example of Italy. In his infamous “Ayacucho Address” (so-called because it was delivered on the centennial of the Battle of Ayacucho, which secured the independence of South America), Lugones lamented the loss of what he considered to be the nobility and heroism of the Wars of Independence and suggested that violence could restore an aristocratic order in Argentina: “Just as the sword has accomplished our only real achievement to date, which is to say, our independence, it will likewise now create the order that we need,” he said. “It will implement that indispensable hierarchy that democracy has to this date ruined—which it has in fact fatally derailed, for the natural consequence of democracy is to drift toward demagogy or socialism.”13

Lugones’s proclamation of the “hour of the sword” would have to wait six more years, however, as the prosperity of the mid-1920s and the relative conservatism of the Alvear administration slowed down nationalist organizing. But when Yrigoyen returned to the Casa Rosada in 1928 and the bottom fell out of the world economy the following year, all the conditions were in place for a military coup. On September 6th, 1930, troops led by General José Félix Uriburu—and was accompanied by two nationalist organizations, the Republican League and the League of May—forced Yrigoyen from office and instituted a military dictatorship.14 Once in power, General Uriburu attempted to create a corporatist state, although political opposition and his own declining health forced him to step down prematurely, deferring this dream until Juan Perón’s rise to power a decade and a half later. Incidentally, the FORA IX’s successor organization, the Argentine Syndical Union (USA), would participate in the 1945 general strike that secured Perón’s release from prison and his ascension to the presidency one year later. The union then dissolved itself and joined the Peronist General Confederation of Labor (CGT), closing out a cycle in which the “pure syndicalist” wing of the labor movement joined the state forces that continued to brutally murder and repress their former comrades.

Following the 1930 coup, many of Argentina’s anarchists went into exile in neighboring South American countries, many of which had militant anarchist movements of their own—there would be anarcho-communist revolts in Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia up through the 1940s, including the 1931 declaration of a revolutionary commune in the Paraguayan city of Encarnación.15 With the establishment of the Second Republic in 1931, many FORA members—including Diego Abad de Santillán and Simón Radowitzky, who both make cameo appearances in Rebellion in Patagonia—made their way to Spain. Members of the FORA and Uruguay’s FORU played an important role in the following years, both in the international debates surrounding the CNT as well as in the civil war itself. And though decimated by repression—Diego Abad de Santillán estimated that, after three decades of FORA activity, over five thousand militants were killed and over 500,000 years in prison sentences were handed out—the union was able to survive under Argentina’s succession of military regimes, maintaining a workplace presence until the last military dictatorship in the 1970s.16

But by the second half of the twentieth century, when Osvaldo Bayer wrote Rebellion in Patagonia, much of this history had been forgotten by the general public and Argentina’s once-vital anarchist movement had become a shadow of its former self, having largely been sidelined by Marxism and Peronism. Due to Patagonia’s distance from Buenos Aires, the 1920–1922 strike wave and subsequent massacre were particularly shrouded in mystery. Bayer himself heard about the events in Patagonia for the first time from his parents, who lived two blocks from the Río Gallegos jail during the repression that followed the strike. They told him that, late at night, they could hear the screams of the strikers being tortured by the prison guards—“My father was never able to overcome the sadness the deaths of all those people caused him,” Bayer would later say.17 Inspired by his father’s stories of the strike, Bayer moved to Patagonia in 1958 and founded La Chispa, billed as Patagonia’s first independent newspaper. In its pages, he defended the region’s workers and indigenous people, but was run out of Patagonia by gendarmes in 1959. In the early 1970s—after abandoning journalism to reinvent himself as an anarchist historian, writing acclaimed books and articles on figures such as Simón Radowitzky and the infamous insurrectionist Severino di Giovanni—Bayer returned to the south to track down the remaining survivors of the massacre. His research would result in his magnum opus, the four-volume The Avengers of Tragic Patagonia, later abridged as Rebellion in Patagonia. The first volume was a bestseller and film director Héctor Olivera approached Bayer to make a movie based on the books. And that’s when the trouble began.

Here it’s worth giving some background on the political situation in Argentina at the time. In 1973, Juan Perón returned to Argentina after nearly twenty years in exile and retook the presidency months later. Though many on the left fondly remembered the pro-labor policies of his first two presidential terms (1946–1952 and 1952–1955), Perón merely represented the left wing of the nationalist movement that had massacred Argentina’s genuine left in the early twentieth century and his support for unions was merely a means towards his ultimate end of creating a corporatist state modeled on Mussolini’s Italy. Any hopes that his return from exile would benefit the left were dashed the day his plane touched down—as Peronists gathered to greet their leader at the Ezeiza International Airport, snipers associated with the right wing of the movement opened fire on the crowd, killing at least thirteen people and wounding some three hundred more. Once in office, Perón fully backed the Peronist right, giving paramilitary organizations a free hand to liquidate Argentina’s independent left. When he passed away less than a year later, the presidency passed to his wife Isabel, who only intensified the persecution of the left.

On October 12th, 1974, Isabel Perón censored the film version of Rebellion in Patagonia—which had won the Silver Bear at the 24th Berlin International Film Festival just months before—and Osvaldo Bayer’s name appeared on the blacklist of the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (AAA), a Peronist paramilitary organization responsible for the assassinations of over one thousand leftists in the years preceding the military takeover. Bayer fled to West Germany, while Luis Brandoni (who played Antonio Soto in the film) ended up in Mexico. Héctor Alterio, who played Commander Zavala (the fictionalized version of Commander Varela), was in Spain when he received word of the AAA’s threats on his life and he opted not to return to Argentina. Jorge Cepernic, elected governor of Santa Cruz the previous year, was forced from office and imprisoned. According to Bayer, Cepernic asked the prison warden if he deserved to be in prison for having promoted progressive legislation during his aborted term as governor and the warden replied, “No, you aren’t a prisoner because of your legislation, you’re a prisoner because you allowed Rebellion in Patagonia to be filmed.”18 After the military forced Isabel Perón from power, the government continued its persecution of Bayer and his works—in April 1976, Lieutenant Colonel Gorlieri ordered all copies of Rebellion in Patagonia to be burned “so that this material cannot keep deceiving our youth as to the true good represented by our national symbols, our family, our Church and, in sum, our most traditional spiritual heritage, as synthesized by the motto ‘God, Fatherland, Family.’”19

And so history repeated itself. The repression unleashed on Argentina’s independent left by a populist president supported by moderate union leaders was echoed by the repression unleashed by Isabel Perón on those who attempted to bring the story to light some fifty years later. “This whole episode meant heartache for me and, with my family, eight years of exile,” Bayer wrote in 2004, thirty years after the film was banned. “But, with the passing of time, the truth is ever greener. Whenever I reread the decree of President Lastiri banning Severino di Giovanni, or that of Isabel Perón, with The Anarchist Expropriators, or the names of those who intervened to hide the massacre in Patagonia from the people, and I see my books in bookstores and the film of Rebellion in Patagonia being screened in special showings, I can’t help but smile: the truth provides a path through the darkness, it can’t be killed forever.”20