Читать книгу Rebellion in Patagonia - Osvaldo Bayer - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

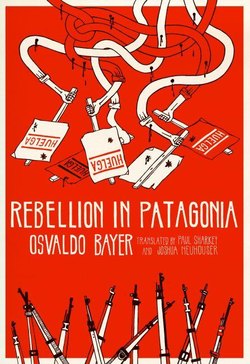

Prologue: The Exterminating Angel

Оглавление“Kurt Wilckens, strong as a diamond,

noble comrade and brother…”

Severino Di Giovanni,

Los anunciadores de la tempestad

By 5:30 a.m., it’s already clear that January 25th, 1923 is going to be a sweltering day in Buenos Aires. A blond man gets on the trolley at Entre Ríos and Constitución and pays the workers’ fare. He is heading towards the Portones de Palermo station, near Plaza Italia. He is holding a package, most likely his lunch or his tools. He seems calm. Shortly after boarding, he begins reading the Deutsche La Plata Zeitung that he has been carrying under his arm.

He gets off at Plaza Italia and heads west along Santa Fe, in the direction of the Pacífico station. After passing the station, he arrives at Calle Fitz Roy and stops in front of a pharmacy on the corner.

It’s now 7:15 a.m. and the sun is already beating down hard. There’s a great deal of foot and automobile traffic. The pharmacy faces the barracks of the 1st and 2nd Infantry. But the blond man doesn’t look in that direction: his eyes don’t leave the door of the house at Fitz Roy 2461.

Is today going to be the day? The answer seemed to be no. Nobody leaves the house. Minutes go by. Had he already left? Does he have any suspicions?

No, here he comes. A man in a military uniform leaves the house at 7:55. But it’s the same as before: he’s leading a little girl by the hand. The blond man makes an imperceptible gesture of exasperation. But then the military man stops and talks with the girl. She says that she doesn’t feel well. He lifts her up in his arms and carries her back inside.

After a few short seconds the military man leaves the house again, alone this time. He’s dressed in standard uniform with a saber at his side. He walks towards Calle Santa Fe on the same side of the street as the blond man. His firm character can be seen in his energetic stride. And now he heads towards his appointment with death on a beautiful, if a bit sweaty, morning.

He is none other than the famous Lieutenant Colonel Varela, better known as Commander Varela. Argentina’s workers despise him above all other men. They say he’s bloodthirsty, they call him the Butcher of Patagonia, they accuse him of having murdered 1,500 defenseless peons in the south. He forced them to dig their own graves, had them strip naked, and then executed them by firing squad. He gave orders for his subordinates to beat the union leaders with the flats of their swords before killing them, always with four shots each.

Does Commander Varela live up to the legend? He does in the eyes of the blond man waiting for him.

Not that the blond man is a relative of any of the executed workers. He has never even been to Patagonia, but neither has he received so much as five centavos in payment for the assassination. His name is Kurt Gustav Wilckens. A German anarchist of the Tolstoyan persuasion, he is an enemy of violence, but he believes that, in extreme cases, the only response to the violence of the mighty should be more violence. And he will follow through on this belief with an act of vigilante justice.

When he sees Varela coming, Wilckens doesn’t hesitate. He moves to intercept him and hides in the doorway of the house located at Fitz Roy 2493. There he waits. Even now he can hear his footfalls. The anarchist leaves the doorway to confront him. But it won’t be that easy. In that precise moment, a little girl crosses the street and begins walking in the same direction as Varela, just three steps ahead of him.1

Wilckens has run out of time: the little girl’s sudden appearance threatens to ruin all his plans. But he makes his decision. He grabs the girl by the arm and pushes her out of the way, shouting, “Run, a car’s coming!”

The girl is bewildered, frightened, hesitant. Varela stops to watch this strange scene. Instead of throwing his bomb, Wilckens advances on his prey while turning his back to the girl, as if to protect her with his body, but she is already running away. Facing Varela, Wilckens throws his bomb on the pavement, between him and the officer. There’s a powerful explosion. Varela is taken by surprise and the shrapnel tears apart his legs. But Wilckens has also been hit and a sharp pain shoots through his body. He instinctively retreats to the doorway and climbs three or four steps, taking a moment to pull himself together—the enormous explosion has knocked the wind out of him. It takes just three seconds. Wilckens immediately descends the staircase. The anarchist then realizes that all is lost, that he can’t flee, that he has a broken leg (his fibula has shattered and the pain in his muscles is agonizing) and that he can’t move his other foot because of a piece of shrapnel lodged in the instep.

As he leaves the doorway, he comes across Varela. Though both of his legs are broken, he manages to remain upright by leaning against a tree with his left arm while trying to unsheathe his saber with his right hand. Now the two wounded men are once again face to face. Wilckens approaches, dragging his feet, and pulls out a Colt revolver. Varela roars, but instead of scaring the blue-eyed stranger, it sounds like a death rattle. The officer is collapsing, but he’s not the type to surrender or plead for mercy. He keeps tugging at the saber but it refuses to leave the scabbard. There’s only twenty centimeters left. Varela is still certain that he’ll be able to unsheathe it when the first bullet hits. His strength abandons him and he begins to slowly slip down the tree trunk, but he has enough time left to curse the man who shot him. The second bullet ruptures his jugular. Wilckens empties the chamber. Every bullet is fatal. Varela’s body is left wrapped around the tree.

The explosion and the gunshots have caused women to faint, men to flee, and horses to bolt.

Lieutenant Colonel Varela has died. Executed. His attacker is badly wounded. He makes a final effort to reach Calle Santa Fe. People are beginning to show their faces. Fearing the worst, Varela’s wife goes down to the street and the poor woman catches sight of her dead husband, his body broken so dramatically.

Several neighbors approach the fallen man, lifting him up to carry him to the pharmacy on the corner. Others follow the strange foreigner who looks like a Scandinavian sailor. They keep their distance because he still carries his gun in his right hand. But two policemen have already come running: Adolfo González Díaz and Nicanor Serrano. They draw their guns when they’re just a few steps away from Wilckens but they don’t need to act because he offers them the butt of his own revolver. They take it away and hear him say, in broken Spanish, “I have avenged my brothers.”2

Officer Serrano—“Black Serrano,” as he’s known at the 31st Precinct—responds by punching him in the mouth and kneeing him in the testicles. His hat—one of those traditional German hats with a wide brim, a cleft crown and a bow on the ribbon—falls off. They take him in with his head uncovered, awkwardly trying to stabilize himself with his wounded legs, like a shorebird with broken feet.

And so begins the cycle of revenge for the bloodiest repression of workers in twentieth century Argentina, save only for the period of the Videla dictatorship. The first chapter was written two years earlier, in the midst of the cold and the relentless gales of Patagonia, far to the south, with the most extensive strike of rural workers in South American history.