Читать книгу He Leads, I Follow - P. Lothar Hardick O.F.M. - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter V

Compelled into Her Characteristic Way of Life

The separation occurred. Neither of the two religious founders had wished nor perpetrated it. God had manifestly employed the talents of both co-founders in order to accomplish more for the church and the whole of mankind. If there had been but one congregation, its activity could not have spread so extensively as with the two of them. One must recognize that the determining factors leading to the separation were not planned by Salzkotten nor by Olpe. Much less were they managed nor brought to completion by them. Those spiritually responsible for the Sisters, especially their spiritual director and the bishop, were the only ones involved during the period of decision. The final decision was contrary to the wishes of Mother Clara Pfaender as superior and Sister Maria Theresia Bonzel as subject. Both had their ideas as to how the crisis could be solved. However, both submitted to the decision of the bishop. Both became enriched by the experience.

The bitterness that these days concealed for both congregations, led them on the way of the cross, a blessing for both. In the great Franciscan Family, both institutes today rank as strong congregations, for both are animated with a fine spirit and render great services. From this point we will not develop further the history of the Salzkotten Franciscans, but to say only this: Mother Clara Pfaender energized the congregation with great ability toward fruitful activity and development in Europe and in North America. What she contributed to the Sisters was manifest in 1880, when it was demanded of all the Sisters to separate themselves from the Mother. At that time Mother Clara went her sorrowful way alone, a tragedy recognized only later. Her spiritual daughters on that occasion demonstrated an admirable, truly heroic obedience in faith to ecclesiastical authority, which later resulted in great blessings for them.

When a congregation arises from an existing one, it is not enough to separate them in leadership and administration. The church demands specifically that the congregations be adequately distinguished from each other: individual name, individual garb, and individual statutes. Just as in transference from one congregation to another, there must be a period of renewed probation followed by profession, this also obtained in Olpe. The church ordains in such instances that life in the threefold profession of vows is no longer valid without renewed ties. Complete religious life is not undertaken by investiture, but a life in compass with the new congregation according to its special obligations. Thus if a new period of probation is required by a congregation and closes with profession, the procedure certainly does not indicate that the former congregation is to be regarded with distrust. The church thereby signifies a new congregation has been formed which follows its own rule and constitution.

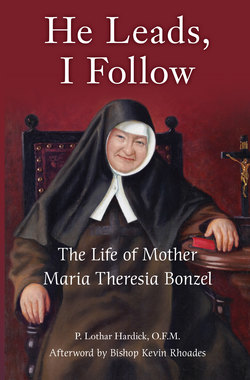

Thus Sister Maria Theresia and Sister Francesca began the framing of a new constitution. They also fashioned a new religious garb, which consisted of an unhemmed coarse woolen undergarment and a like habit with a white cincture. As footwear only sandals were considered. The head covering consisted of a white cap protruding somewhat in the front; a strip of stiff white paper was set in the seam to give it a definite and firm shape. A black veil was draped over this with a large overflap in front which could be lowered over the face when going out of doors. The mantle worn by the Sisters was of the same style as commonly worn by Franciscans. After the test of daily wear some changes were made in the religious garb. Shoes were permitted. The sisters lived in the Sauerland which is noted for its cold and snowy winters. The practice of lowering the veil over the face when leaving the convent was also discontinued. It savored too much of contemplative orders and was impractical for active orders. A scapular with a black cross sewed on it was added. The garb of the Olpe Sisters remained essentially unchanged for almost one hundred years, until the present era when a modernized form was adopted to meet the present situation. The pictures of the original religious garb of the Olpe Franciscans reminds us forcefully of the way the Poor Sisters of St. Francis in Aix-la-Chapelle (now called Aachen) wore their veils. The foundress of the Aix-la-Chapelle Sisters, Mother Francis Schervier gave much to the Olpe sisters and shared ideas with them. Probably the new name of the congregation, “Poor Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration,” was a suggestion from the “Poor Sisters of St. Francis.”

In Reverend Schmidt from Wenden, the congregation had a director who did all to give it a genuine foundation. He energetically set guidelines to overcome the difficulties of beginning. This exemplary, zealous, and devout priest was himself a member of the Franciscan Tertiaries. In all probability that increased his interest to support Sister Maria Theresia’s idea of guiding the formation of the Sisters of the congregation according to the spirit of St. Francis. He wished a Franciscan priest to come as soon as possible to fire the Sisters with the genuine spirit of St. Francis by giving them an animated retreat, so he wrote to the guardian of the Franciscan monastery in Düsseldorf for a suitable retreat master. In that letter he made an amusing error in expressing his desire that the Rule of the First Order of St. Francis be introduced to the Olpe Sisters to be adopted by them. He most likely reasoned that the Second Order of St. Francis was that of the Poor Clares and the Third Order that of the people of the world, and the First Rule for all the others. The guardian in Düsseldorf, Reverend Aegidius Jonas, set him right in his answer of September 13, 1863. He referred to the Third Order Regular of St. Francis which in conformity with its statutes could form a good foundation. Regarding a retreat master, he referred him to Provincial Othman Maasmann.

On October 23, 1863, Reverend Schmidt wrote the following, among other things, to the provincial:

The Olpe Sisters now numbering ten have in addition to the Perpetual Adoration added another objective – caring for poor, orphaned, and neglected children. They now have forty children in the house. The Sisters desire to live as genuine Franciscans according to the Rule of St. Francis. Their way of life meets the warm approval of the bishop. The undersigned priest, spiritual director of the Poor Franciscans in Olpe, begs Your reverence in the name of His Excellency the bishop to send a suitable priest of your order in the near future to give the sisters a retreat to introduce them into the Franciscan way of life and ordain what is prescribed by the precepts of the church that this congregation may enter into a genuine union and the graces of the Seraphic Order. If any definite preparations are to be made, please advise me.

The provincial answered immediately and on October 26, 1863, wrote: “In compliance with the wish of the Most Reverend Bishop Konrad Martin, I shall send a suitable priest to Olpe as soon as possible for the specified purpose.” Thus in November of the same year the Reverend Bonaventure Wessendorf came to Olpe to give a spiritual retreat to the Sisters. The Franciscan Province of the Holy Cross, Saxony, could scarcely have sent a more suitable priest for this task. Holy in his way of life and blessed with an all-embracing spirituality, he was well qualified because of his rich experience. He was the spiritual director of Mother Francis Schervier, foundress of the Poor Sisters of St. Francis of Aix-la-Chapelle. This very fact alone should prove very significant for the Olpe Sisters.

Sister Maria Theresia in her intensive discussions with Father Bonaventure Wessendorf concerning the formation of the congregation had most likely reiterated her desire of having an experienced religious come to Olpe who with advice and deed might help in the difficulties of beginning. Father Bonaventure encouraged the Sisters and promised to commend them to the bishop of Paderborn. His report to the bishop concerning the Sisters and their congregation had good effects. The bishop agreed favorably with all the suggestions submitted by Father Bonaventure for the development of the congregation.

In Olpe Father Bonaventure had promised the Sisters that he would see that Mother Francis Schervier would assist them with valuable counsel through her fruitful experience and give them the correct introduction into religious life. God provided that he soon had the opportunity to contact Mother Francis for shortly thereafter she came to Paderborn. When Father Bonaventure presented his request, she was prepared to do her utmost, and promised that she herself would go to Olpe. The Sisters were not complete strangers to her for the three founders had visited at the convent of Aix-la-Chapelle in the beginning of October 1859. At that time she had given each a copy of the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary as the first equipment for the religious life. Father Bonaventure must have realized her wholehearted selflessness when, in addition to the great task as Mother of her own congregation, he asked her to be concerned in the same way with another congregation. When Sister Maria Theresia wrote in the Chronicles that “this servant of God was prepared to shy from no sacrifice that concerned the honor of God,” her every word carried its weight.

Most assuredly Mother Francis had intended to go to Olpe as soon as possible. But the pressing work as major superior of a rapidly growing congregation held her bound to Aix-la-Chapelle. Sister Maria Theresia saw the danger of further uncertainty clearly. She consequently engaged in a written correspondence with Aix-la-Chapelle, and in February 1864, went there to discuss urgent matters with Mother Francis, for some questions pressed for decision. When she and Sister Francesca, her assistant, arrived in Aix-la-Chapelle preparations for investiture ceremonies were in progress. Sister Maria Theresia later wrote in the Chronicles that at that time in Aix-la-Chapelle “many candidates” were invested and among them was the Countess Merfeld. The uncle of the countess, the Most Revered Bishop von Ketteler of Mainz, was officiating officer at the investiture ceremonies. How small and insignificant the two Sisters from Olpe must have felt as they experienced the rhythm of a strong and growing congregation in Aix-la-Chapelle! The Olpe congregation numbered only ten Sisters! They rejoiced on February 12, when Regina Schaefer of Olpe became their first postulant. Their Community could not be compared with what they saw in Aix-la-Chapelle. Would it not be natural to lose courage under such a situation?

Owing to the numerous guests who came to Aix-la-Chapelle for investiture, the two Sisters were housed in Burtscheid, an affiliation of the congregation. As soon as the celebration was over Mother Francis with sincere love extended motherhouse hospitality to them. Now they could communicate all their problems and worries to this great servant of God. They confided all to her as to a mother, as seen in the following instance. Sister Francesca Boehmer was in great spiritual need for she feared she might not have been baptized validly. Her Protestant mother had her baptized by a Protestant minister who had the reputation of not performing his obligations conscientiously. Mother Francis solved this need by having Sister Francesca baptized conditionally by a Franciscan priest, Reverend Romuald Terhaag; she herself was sponsor. Thus this point was solved satisfactorily.

What seemed the most pressing problem at that moment was the discussion of a well-intentioned plan by the director, Reverend Schmidt, to establish a governing body as help and security for the Sisters in Olpe. The members were to manage the external business of the congregation. Mother Francis recognized such a governing body as one limiting the policy-making decision of the young congregation and circumscribing it greatly. Lay personnel would assume the right of making decisions. She objected resolutely to the plan. Urged by experience she counseled the congregation to keep itself free and independent. Upon her return to Olpe, Sister Maria Theresia informed Superior Schmidt of Mother Francis’ decision. He gave up the plan immediately, although he had developed the program rather extensively and had outlined it on paper.

Before the two sisters left Aix-la-Chapelle, Mother Francis told them that she would visit them in Olpe at her earliest convenience to help regulate all necessary matters there. It was June before she could keep her promise. At this time she learned to know the Sisters’ way of life and to give them wholesome counsel. She was convinced that zeal was not lacking and that their overzealous spirit must be tempered with wisdom. At this time Sister Maria Theresia again attempted to evade the responsibility of founding a congregation. Together with Sister Francesca she pleaded that their congregation be accepted into the Aix-la-Chapelle congregation. Mother Francis felt the great sincerity in this request made with such humility. She on her part also demonstrated humility, for she did not consider the aggrandizement of her congregation through an easy annexation of another house in a new area. Through such a maneuver she would have rewarded herself for her service in Olpe. She, however, acted in accordance with the will of God and placed her experience and knowledge at the disposal of others as instruments of the Lord. She also recognized that the Olpe Sisters were called by God to follow their own way of life; at least, they must try it. She told the Sisters that they should proceed on their own specific way with great confidence in God. Should it become apparent that they could not possibly succeed, then and only then would she be prepared to integrate the Olpe congregation into her own.

Superior Schmidt also took this opportunity to discuss all problems with Mother Francis. Seemingly, he took no offense that she objected to his plan of a governing body. To him, also, she spoke of her willingness to be of assistance in every possible way.

Because of this proffered assistance, Sister Maria Theresia was able to go to Aix-la-Chapelle for a spiritual retreat and remained at the motherhouse there for an additional six weeks. She was permitted to take part in all conventual exercises. Her objective was to learn the right way of religious living through first-hand experience in a well-regulated congregation. She realized that entering exactly into the spirit was the best way of learning that life. At this time also she was briefed by Mother Francis Schervier concerning all particulars and important matters regarding the formation and guidance of a congregation. In the six weeks she had ample opportunity to ask questions.

Mother Francis in the interim had the opportunity to mull over the impressions of her visit in Olpe and was now able to present her ideas in a more instructive way. She had no need of exhorting the Sisters to zeal, mortification, and penance. On the contrary, it was even a question of too much zeal in adopting extraordinary austerities as penance. These penances required the reins of wisdom. She counseled moderation and later advised urgently against such daily penances as the discipline, the penitential belt, fasting and the like, and counseled to abandon them. There was danger lest the young enthusiastic religious would soon undermine their energy and health. She also advised that the coarse clothing be changed, for associations with children and the sick make frequent laundering a necessity. She advocated linen wear.

During these hours of reflection Sister Maria Theresia realized ever more clearly the plan she was to follow in guiding her congregation according to the will of God. In Aix-la-Chapelle she was a great learner. Many ideas began to mature, thanks to the kind instructions she received. She did not conduct herself as one realizing her own mission, nor as one who waives advice from others relative to things which concern her alone and should be managed by herself. Because she sought and accepted counsel from the wise, she spared herself and her Sisters many an experiment and many a bitter experience. In regard to Mother Francis Schervier it must be said, she did what is exceptionally rare in religious congregations.

As foundress of a flourishing congregation, she in a selfless way placed her experiences at the disposal of a newly founded sisterhood. She advised that this new congregation maintain its own character, for in serving the will of God, she did not present her own congregation as a standard for all things. Whoever regulates his life entirely according to the will of God is capable of seeing the will of God in others and will not impose upon them his own way of life.

How grateful the foundress in Olpe always felt toward the foundress in Aix-la-Chapelle is seen from the letter she wrote shortly after the death of Mother Francis, on December 17, 1876, to Aix-la-Chapelle. Therein she called her a “dear spiritual mother and counselor in all things.” When she learned that a biography of Mother Francis was to be written, she expressed in detail her many reasons for gratitude to this great woman. In her letter of May 22, 1887, to Mother Vincentia in Aachen she mentions these with other statements:

Our congregation has experienced the self-sacrificing love and benevolence of this good and venerable mother in manifold ways. I would be glad if the following statement could be inserted (in a biography) as a manifestation of our gratitude. In April of the year 1864, accompanied by another Sister, I made a trip to Aix-la-Chappelle to seek counsel from Mother Francis and to beg her assistance. We found her prepared for every sacrifice for the glory of God; she promised to come to Olpe and arrived at our convent in July of the same year. The good mother remained with us for several days; she helped us in difficult situations, instructed, and directed the Sisters of the young congregation in their conventual exercises. She gave wholesome counsel and won the love and confidence of the Sisters and also the respect of all who had the good fortune to come in contact with her. She showed a special love for the children in the orphanage and loved to spend some time with them. Before she returned, she promised that if possible she could continue her care of our congregation — and this she did.

In the fall of the same year she caused great joy by offering me the opportunity to make a spiritual retreat in the motherhouse at Aix-la-Chapelle and thereafter remain for six weeks to study the organization of their convent and learn what might be beneficial to our own. When in Olpe, the venerable mother had noticed that our chapel lacked some necessities for the worthy celebration of the Sacred Mysteries. She supplied a chasuble, rochet, and stole. We experienced her generosity again in a supply of office books and others for spiritual reading. For all we are most grateful.

When after several years I informed the dear mother that our assistant, Sister Francesca, was suffering from tuberculosis and that a change of air was recommended for her, she lovingly provided that the sick one come to Aix-la-Chapelle and was devotedly cared for there by the Sisters. Up to that time our Sisters had very little experience in the care of the sick. The venerable mother arranged that two of our Sisters be educated in nursing care in Euskirchen. For the same reason, she provided that two other sisters be admitted to the nursing school of the large Hospital of Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Aix-la-Chapelle. I went to her often in difficult situations for counsel. A friendly correspondence was constantly carried on between us. At that time as well as at present, there was good rapport between the congregations. We were sincerely grieved by the illness and quick death of our dear and unforgettable Mother Francis who had done so very much for us. She who in life manifested such great love for us in so many ways will also intercede for us above that, after we have served our purpose well here, we shall be united again in heaven.

In the beginning of her account, Mother Maria Theresia expressed the wish to have her sketch included in a biography of Mother Francis. In fact, Reverend Ignatius Jeiler used this valuable contribution scrupulously in his biography of the Aix-la-Chapelle foundress. One senses Mother Maria Theresia’s great gratitude in every sentence. Even later after her own congregation had grown strong and she felt secure, she ever maintained the role of learner.

After the death of Mother Francis, she requested a photograph of her and a small personal remembrance. When in 1867, her Sisters adopted a definite religious habit, the style chosen closely resembled that worn by the Sisters of Mother Francis. The Sisters wore this garb practically unaltered until 1960. It cannot be established definitely whether the similarity of religious habit was chosen intentionally or not. But certainly it points to the close spiritual relationship between the two congregations.

After her period of apprenticeship, as one may readily call the time she spent in Aix-la-Chapelle, the returning superior was confronted by three weighty questions in addition to her daily cares; the redrafting of the Constitution, a legal foundation for the orphanage, and an economic basis for the congregation in respect to the inheritance of Mother Theresia herself. Of course, these problems did not arise at the moment, but for some time had been awaiting cooperative decisions. Since all three questions were of greatest importance for the efficient development of the small congregation, the Sisters were greatly interested in all of them. It is to be noted that in the question of their own inheritance, which touched the Sisters so closely, they manifested the greatest reservation.

Economic Security of the Congregation Through the Inheritance of Mother Maria Theresia

What was the situation relative to the inheritance of the Widow Bonzel to her eldest daughter? In an order without any exterior apostolate, such as the contemplative order of the Poor Clares, the question of an economic basis is not so important although here also it plays a role. But in an active order serving in an educative or in a nursing capacity, a secure economic basis is wise and all-important. Only under such conditions can the congregation follow its apostolate of charity. Under other situations love soon becomes exhausted by the many demands for consolation and encouragement placed upon it. Consequently, there can be no valid objection to the influence the Bonzel family exercised in the decision of 1859, to make the original establishment in Olpe, and again in 1863 to have at least a foundation in Olpe. Considerations for establishing the motherhouse in Elspe were discussed earlier. These were abandoned lest the foundation would not have the economic backing of the Bonzel family and consequently lack a sound economic basis.

The first transfer of abode for the young congregation was from the so-called Schuerholz House. For this, the Sisters were grateful to Mrs. Bonzel. After Easter in 1860, Mrs. Bonzel purchased the Zimmermann House as a dowry, to be divided equally between her two daughters Aline and Emilie. An uncle of Sister Maria Theresia bequeathed an inheritance of real estate and between four and five thousand Reich dollars to his niece. Mrs. Bonzel also purchased the so-called Weber House for a motherhouse in Olpe. To have the diocese of Paderborn purchase the property was under deliberation for a long time. The experience in Italy, however, was fresh in their memories, in which the political unification of Italy with one stroke confiscated all convent and church property. Dean Goerdes in his letter to the bishop dated April 16, 1861, had counseled the bishop not to make it too easy for “rapacious hands” to obtain possession of convent property, if in Germany as now in Italy, the hour of visitation should strike. Did he have a premonition of the Kulturkampf? At all events his counsel was followed by Mrs. Bonzel, for the purchase of real estate and a house was transacted in her name.

The question concerning the inheritance of Sister Maria Theresia Bonzel, especially a suitable gift to the Episcopal See in Paderborn, busily engaged Reverend Schmidt. A long and extended correspondence resulted between him and the General Vicariate. Mrs. Bonzel rightly exercised justice to her second daughter Emilie also.

The fact that Reverend Schmidt assumed the difficulties of negotiating these personal matters manifests his great zeal as spiritual director of the Olpe congregation. He spared no hardship to bring this affair to a successful conclusion. Seemingly, Sister Maria Theresia personally did not enter into any of the deliberations. In the negotiations, there is no trace of her attitude toward the question. That she understood the problem is certain. In all these negotiations no one questioned her in regard to the facts because she remained silent throughout. At that time she was a subject; the reins of authority were in other hands. She took the expression “Poor Franciscan” very seriously. For this reason, Director Schmidt had a poor assistant in her. After the prospective donation to the Episcopal See had been considered and justly approved, difficulties arose between the sisters of Salzkotten and those of Olpe.

Thus Reverend Schmidt was obliged on June 20, 1862, to report the following to the General Vicariate:

Because of a higher mandate, I contacted Mrs. Bonzel in Olpe yesterday concerning the settlement of the donation to the episcopal See. She mentioned that a settlement would be impossible until the confused situation of the Franciscan congregation becomes stabilized and the convent becomes secure. She declared her willingness to place the entire inheritance at the disposition of the bishopric. But since the property is the dowry of her daughter, Sister Maria Theresia, she cannot contract that until there is certainty that the future of her daughter is secure. She begged that the settlement be postponed for the present until the investigation relative to the Franciscan superior be concluded — since her reasons are fundamental, I am not in a position to oppose her views and her explanation.

Only on November 16, 1863, was Revered Schmidt able to inform the bishop that he had again contacted Mrs. Bonzel concerning the donation. On October 4, 1864, the negotiations were finally and definitely closed. By signature Mrs. Bonzel ratified the transaction through which the property of the Olpe orphanage, secured through the dowry of her daughter Aline, now Sister Maria Theresia, was transferred to the Episcopal See in Paderborn. The pastor of St. Martin Church in Olpe, Reverend Hengstebeck, accepted the property in the name of the Episcopal See in recognition of the terms stated in the contract. In substance these terms were: the Episcopal See accepted the gift donation for the foundation of an institution in Olpe for the care of neglected and poor orphaned children. This institution was assigned to the management of the Poor Franciscans. If said congregation should cease to exist, the orphanage was to be reassigned to another Catholic congregation. This gift contract was also licensed by civil authority on March 1, 1865.

One may ask why such a complex negotiation was pursued. The reason is found in the first statute of the congregation in Chapter II, Article 3, which states: “Poverty without property. As daughters of St. Francis the congregation possesses no property and utilizes a house with garden and real estate loaned by the bishop.” These statutes were not approved by the bishop until July 6, 1865. But the provisions for a life of poverty without property had to be set up beforehand. Sister Maria Theresia understood St. Francis of Assisi’s concept of poverty very well. She endeavored to introduce this same idea of poverty into her own congregation, the essence of which is based on the abrogation of all possessions and claims to possession. In Franciscan orders, the Pope possesses the right of all property servicing the order. In the young congregation in Olpe, the Episcopal See in Paderborn possesses the right and exercises proprietorship when the congregation has to testify. Ten years after the so-called Kulturkampf, this very contract was the cause of much sorrow and grief and even occasioned a lawsuit. More on this point later.

The avowal of Franciscan poverty was the only reason in the foregoing of the gift contract. Although Sister Maria Theresia apparently did not enter into the difficult and laborious negotiations, these, however, were necessary because she wished poverty without property. However, this was not the only way that the title “Poor Franciscan” was justified. The first stages after the separation brought day-by-day evidence of actual poverty in Olpe. The Chronicles of the Congregation report concerning these days: “Poor as the life of St. Francis also should be the life of his daughters; and as the ‘poor’ Christ, their life of privation should also resemble that of the poor.” Poor were the accommodations of the convent, poor their hard straw beds, poor their simple table. How often the Sisters lacked even the bare necessities and had to beg bread for the orphans from generous benefactors. Frequently the Sisters had no money whatever on hand. When a Sister was obliged to take a trip they resorted to the poor box. If nothing was found therein, they had to borrow money. Then the Schmidt Brothers, or the Loeser, Bonzel, and Kaufmann families came to the rescue. One or the other of these always gladly helped in every situation. Although the Sisters themselves lived the life of poverty, they were ever solicitous that the orphans were well supplied in all their needs. At this time the bed sheets and other linens were used for the orphans, and only later after nine postulants entered did the congregation obtain sufficient money from their dowries to supply the convent with the needed linens.

Regulations for the Orphanage

In October of the year 1863, the “orphan sisters,” as the people of Olpe called them, cared for forty orphans. These children were their chief concern. From the very beginning they were active in this apostolate for in this sphere of activity they feared no opposition from the other religious congregation. Consequently, it was of special concern to the superior, Sister Maria Theresia, that the orphanage be established on an adequate legal basis. That also, in retrospect, had necessitated the gift contract of Mrs. Bonzel to the Episcopal See. The pivotal point of this gift was that she succeeded in this for the benefit of the orphanage in Olpe. Therefore a suitable statute for the orphanage was an urgent task, and obviously it was framed after the visit of Mother Francis Schervier to Olpe. The document is dated August 1, 1864. Its plan followed that of Reverend Superior Schmidt’s statute for the proposed but relinquished sanatorium. It ensured corporation rights to the Sisters.

Statute for the Orphanage of the Poor Franciscans in Olpe

1. Under the title of “Poor Franciscans” a congregation of women has been formed in Olpe, the chief town of the district, whose main objective is to care for and instruct neglected and orphaned children in Olpe, and if desired in other areas also; however, other works of Christian charity are not to be excluded.

2. In admitting children, first priority is given to those of the Catholic parish and the district of Olpe. When the authorities of this district wish to admit such children, their requests should be granted as far as possible. Children from outlying areas whose instruction and education are in greatest danger are to be given the preference.

3. According to rule, children are admitted after the completion of the second year. However, urgent conditions may dispense with the age rule.

4. Admissions are granted through the decision of the superior and her council. In exceptional cases, the decision depends upon the spiritual director.

5. The children begin their elementary education at the age of six years. They attend classes in the orphanage and are taught by a qualified Sister or instructor. Girls are instructed in all the feminine arts and housekeeping: knitting, patching, sewing, washing, etc. In their free time the children are urged to engage in domestic work and lighter tasks of the garden and the fields.

6. Instruction and practical training of the children for later life come to pass in a stabilized and well-regulated house under the constant observance of ecclesiastical and also civic regulations. The congregation must keep abreast of developments to revise its instruction and education as well as the diet and rearing of children accordingly.

7. Ordinarily, children are not dismissed from the orphanage until they have completed their elementary education. However, those who remain incorrigible in spite of all counsel and endeavors to turn them to better ways and who consequently give bad example to the other children, are dismissed by the superior with the consent of the spiritual director. These children are returned to the care and watchfulness of those who had previously arranged for their admission to the orphanage.

8. The Sisters will consider it their duty to arrange for the moral well-being and favorable placement of those children leaving the institution. They will continue to regard these children as theirs and take the place of father and mother with reference to them. They will preserve contact with the children by inviting them on Sundays from time to time to visit the orphanage together with their teachers or employers to influence their further educational development. For those children who left in good standing the orphanage remains a home where they can spend their days of vacation or the intervening days in a change of employment.

9. All that pertains to the economical or the spiritual life of the Sisters is under the jurisdiction of the diocesan bishop, who is represented by a director.

10. For nourishment, clothing, instruction, and education of the children, the congregation utilizes the means at its disposal (cf. 12), also donations, the work of the Sisters and the children, and prospective collections. In addition, the rule prescribes an annual charge to be paid for each child accepted in the orphanage. In exceptional situations, this sum may be reduced or remitted altogether depending upon the circumstances of the congregation. If public funds are given to the congregation for specific purposes of education or charity, the institution is to render an account of expenditures to the administrative authority.

11. Together each evening the Sisters and orphans pray for their benefactors in the chapel of the institution. During the octave of All Souls they hold a solemn anniversary for all deceased benefactors of the orphanage, either in the chapel of the institution or, pending the consent of the pastor, in the Olpe parish church.

12. The Congregation of the Poor Franciscans of Olpe, organized for the care and education of orphaned and neglected children, transferred property by a legal donation to the Episcopal See in Paderborn. This property at present consists of a large house with real estate and garden valued at ten thousand dollars.

13. The superior of the orphanage functions in all legitimate civic relations and performances. All important economic negotiations of the congregation that exceed the value of one hundred dollars, such as acquiring additional property, sale of immobile property, building, borrowing, or lending capital, require the approbation of the diocesan bishop. In all such matters the congregation is also subject to civic regulations.

14. If the congregation of the Poor Franciscans of Olpe should unite with another congregation, then that congregation should likewise agree to operate the orphanage. Should this congregation, however, dissolve, or in any way be dissolved, then the diocesan bishop is empowered to transfer the operation of the orphanage to another congregation.

This statute was signed by Director Reverend Schmidt on October 5, 1864, who then sent it to the bishop for his approval, which was received on January 7, 1865.

In many respects the Statute of the orphanage mirrors exactly the existing situation in Olpe at that time. For instance, Paragraph 14 states the possibility of the Congregation of Olpe Sisters uniting with another congregation. This was not mere theory. It had a factual background. For at that time there was uncertainty that the congregation could survive on its own. Sister Maria Theresia had endeavored to unite the Olpe congregation with the Franciscans at Aix-la-Chapelle. Mother Francis Schervier had declined. She thought that an attempt should be made in Olpe, and if the going was simply impossible, then the question of union could be considered further.

Although several points refer directly to the Olpe orphanage, they have much wider significance. There is, as example, mention made of working in other places. Thought is given to expanding the apostolate. In Paragraph 1, relative to the objectives of the congregation, mention is made for the instruction and education of “neglected and orphaned children in Olpe and also in other areas, if requested.” That Perpetual Adoration is not mentioned here as the chief objective can readily be understood. The statute for the orphanage is an instrument of public and civic character. It states that “other works of charity are not excluded.” A very wise and prudent formulation! The statute of the first beginning in Olpe spoke much more directly of the special objectives of the congregation as not only “care, education, and instruction of youth, but also the nursing of the sick in hospitals, homes … and in general, the practice of all needed works of charity.” In the meantime added knowledge was acquired. The bitter conflicts over the care of the sick were heated. Thus, no one spoke openly of the fact that the Sisters considered working at other charitable activities, including the care of the sick. They not only desired the right to care for the sick in special situations only, but to include it among the works of the active apostolate.

In Paragraph 5, there is a statement to the effect that elementary schooling will be provided in the orphanage itself by a qualified Sister or a lay instructor. This was a goal-setting regulation. Prior to this time, the congregation had made no provision for the preparation of teachers. It was necessary to provide for teacher certification. In the beginning the orphans were instructed by a lay teacher. Miss Tillmann was the first to undertake this task. In the meantime, two postulants entered on October 18, 1864, Regina Schaefer and Sybilla Heiliger. Both began study immediately to prepare for teaching. The assistant headmaster Lohre instructed them in the various subjects. For this purpose he donated his free time, which was not very plentiful, for besides this, he managed a large industrial school. Consequently, he came early in the morning, even before Mass, to teach the two postulants. This was a great sacrifice on his part, and also a great hardship on the postulants. Later, the two candidates went to Karthaus near Trier to continue their studies under the Franciscans. After they had successfully passed the certification tests, one of the sisters was able to take the place of a lay instructor in Olpe.

It was very important in the beginning to choose the right spheres of work. To bake hosts, a task begun in early 1865, could well be combined with Perpetual Adoration. To acquire this skill the assistant, Sister Francesca, spent some time in Koblenz with Sisters from Aix-la-Chapelle Franciscans. Certainly in the apostolate of a large congregation, this task is not in the foreground. But one must also consider the small congregation, which in this way can contribute toward the celebration of Holy Mass in many parishes. Did not St. Francis also supply his brothers with hostbaking irons that they might contribute toward the worthy celebration of the Holy Eucharist?

The education of the Sisters in the care of the sick began in 1868. After a request for their training had been made to Superior Kaiser of the city hospital in Cologne without results, Sister Maria Theresia turned to Mother Francis Schervier. This worthy helper in need for the Olpe Sisters made it possible for two Sisters to be sent to Euskirchen in November 1868, to become proficient in the nursing of the sick from the very rudiments. Two other Sisters went to Essen where in a hospital conducted by the Elizabethan Sisters they learned the nursing of the sick. The fifth and sixth Sisters went to Aix-la-Chapelle to study nursing care in St. Mary Help Hospital. For all this assistance the Sisters were grateful to Mother Francis Schervier.

Thus in large measure, the apostolate of nursing the sick was made possible. It was evident to the superior of the Olpe Sisters that the effectiveness of the sisters in active charitable works does not depend upon good will alone. Sister Maria Theresia herself had not the experience of a special education in any specific field. But she did all within her power that her Sisters become highly qualified through the best education to render possible a rich and fulfilling apostolate.

The First Constitution of the Congregation

The chief endeavors of Sister Maria Theresia were concerned with the inner development of her Congregation of Sisters. Essential to this formation was their very own constitution. The drafting was not to be done hastily. Too much depended upon it. Not that the congregation have a constitution of some sort, it must be good and conform to the best — that was of greatest importance. It was understood from the very beginning that the Olpe Sisters must have conventual regulations. The general character of the new constitution was foreshadowed in the letter Reverend Director Schmidt wrote to Bishop Konrad Martin on August 10, 1863. His statements are almost prophetical:

Should a religious congregation endure and not carry the germs of dissolution within itself from the very beginning, it must above all endeavor to be what its name signifies…. If the sisters are to be genuine Franciscans, the congregation will receive graces from above and will coalesce with the Catholic people, as the Franciscan Fathers, and will thus have a glorious future. Therefore they must imbibe all that is Franciscan in so far as is compatible with religious women. First there is the Rule of St. Francis … closely allied therewith is the clothing … all must bear the imprint of poverty, and this makes the greatest impression on the people; one also witnesses by his so highly treasured worn habit, grown old together with him.… If the Sisters, I repeat again, become true Franciscans, interiorly and exteriorly, then their future is assured.

Bishop Konrad Martin himself had counseled in August 1863 that the Olpe Sisters should frame a constitution based on the Third Order Regular of St. Francis. Utilizing this as a basis they should add their own worthwhile experiences.

All who were in any way concerned, with one accord, manifested a favorable spirit. From the very first, the will of the Olpe Sisters was in agreement with that of Director Schmidt and also with the expressed wish of the bishop. It now depended essentially upon Sister Maria Theresia to activate the wishes and the task. She had no desire to frame the new Constitution solely upon her own decisions. She wished to integrate her congregation completely into the great family of the saint of Assisi, and therefore sought counsel in following the Franciscan way of life exactly. She and all her Sisters made a retreat conducted by Reverend Bonaventure Wessendorf to induct them into the Franciscan way. For the same reason she took counsel from the great Franciscan Mother Francis Schervier, to profit from her rich experience. Although she alone had sought counsel from this great religious woman in Aix-la-Chapelle, she provided that all her Sisters gained deeper knowledge of Franciscanism from Mother Francis during her visit in Olpe. The superior in Olpe did not wish to have this knowledge for herself alone and thus be the only one to give it to others. All Sisters from the very beginning should be informed in the Franciscan way of life. When her assistant, Sister Francesca, was in Koblenz to acquire the skill of host-baking, she had many opportunities of speaking with Mother Francis, who also at that time was there. Upon Sister Francesca’s return, she and Sister Maria Theresia drafted the Constitution. They completed the work on March 25, 1865.

Since the Constitution breathes the genuine spirit of the first beginning, it is an especially primary document, and we shall enter somewhat deeper into it. The manifestation of its spirit is a permanent testament for the Poor Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration. We shall explore the characteristic features and observe especially the situation existing at that time. The Rule of Pope Leo X written for the Third Order Regular of St. Francis in 1521, and used as a basis, appears first. Then follows the Constitution. The objectives of the congregation are given first as follows: “After the example of our holy Father Francis, the Sisters will endeavor to unite the contemplative with the active life: in the Perpetual Adoration and in the practice of works of charity.”

“After the example of our holy Father Francis” — when one considers the foregoing — a person senses how much there is in the first words and how great the reaction. Francis serves as a guideline along which the congregation is to formulate its way of life. This guideline of the saint of Assisi, is not determined by insignificant, individual, and external ways, but from the basic goal here established: “the contemplative life combined with the active life.” Here in this synthesis of the contemplative and the active is expressed the fundamental characteristic trait of St. Francis. When one considers his prayer life, one gets the impression that he must have been a contemplative through and through. If one follows his active life, then he appears an outstanding example of the active orders. Nevertheless he united both in a unique way within himself. His contemplative life made him clearly recognize the will of God who called him to the service of others. In the midst of active life he was never in danger, even in the most absorbing activity, of losing himself in the activity. He was active but not enamored of the activity; he loved the will of God. He saw the contemplative and the active life not as two separate entities, but as one life — the contemplative seeking and discovering the will of God and the active fulfilling it in order to know God more intimately.

This synthesis of the contemplative and the active life finds its expression for the Olpe Sisters in the “Perpetual Adoration and in the active apostolate of charity.” Combined, both are clearly defined literally: “Through the Perpetual Adoration of our divine Lord in the Blessed Sacrament, the Sisters seek to make atonement and to pray for the general intentions of Holy Mother church. In the active apostolate the congregation pursues principally the instruction, education, and development of youth, especially poor, neglected and orphaned children.”

The Franciscan way of life is also expressed thusly: “The Sisters live according to the Rule of holy Father Francis as approved by Pope Leo X for the Third Order Regular with the exception of those changes appearing in the Constitution.” Historically, it is not quite correct to call the “Leo-Rule” the Rule of St. Francis. Does not this very point in its formulation betray the great joy of really belonging to the family of St. Francis? That the statutes deviated from the “Leo-Rule” was caused by necessity owing to the character of that Rule. Some of its regulations were no longer observed in the nineteenth century, for example, those regarding the divine office and the reception of the sacraments. The rule of fasting needed to be modified although the Olpe statutes had endeavored to adhere strictly to the “Leo-Rule.” Through personal experience the Sisters realized that a change had to be made and the severe rule mitigated. The “Leo-Rule” was not formulated for an active apostolate of charity, but for the contemplative orders. The effect of all this was that in 1927, the church gave a new rule to the Third Order Regular of St. Francis, more in keeping with the character of an active apostolate.

Also, the mention of the three vows is entirely in keeping with the character of St. Francis: Poverty without property, chastity, and obedience. The addition “without property” to poverty indicates the wish of the poor man of Assisi.