Читать книгу Frida Kahlo. Her photos - Pablo Ortiz Monasterio - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFRIDA KAHLO, HER PHOTOGRAPHS

Hilda Trujillo Soto

The Frida Kahlo Museum

Photography was a key influence on Frida Kahlo’s work. This was because of the early contact she had with visual images due to her father’s occupation, and later on, because of her close relationship with photographic artists whom she befriended, like Tina Modotti, Edward Weston, Nickolas Muray, Martin Munkácsi, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Fritz Henle, and Gisèle Freund, among others.

Thoroughly and lovingly, Frida amassed a vast photographic collection. In it, we can find photographs that must have belonged to either her family or Diego Rivera. However, it was she who took the trouble to keep them. The artist was undoubtedly fond of these beloved objects―she would alter them by adding colors and lipstick kisses, by mutilating them or by writing her thoughts on them. She cherished them as substitutes for the people she loved and admired, or as images portraying history, art, and nature.

Through the means of photography, devised in the 19th century, Frida knew and used the artistic power of images. Either in front or behind the camera, Frida Kahlo developed a strong, well-defined personality, which she managed to project by means of an ideal language―photography. Her relationship with Nickolas Muray, an outstanding fashion photographer for magazines like Vanity Fair or Harper’s Bazaar, illustrates the way Frida established a natural connection with the lens. Many of Frida’s finest and best known pictures were taken by the Hungarian-born American photographer. However, the photographs that Muray took while Frida was in the hospital, painstakingly painting her pictures, also stand out for their crudeness. These images greatly contrast with those in which we can see her before her surgeries, flirty and challenging, as she naturally was. Despite the excruciating pain that tormented her, Frida never lost her fascination for the camera, a device she always thought of as an instrument for portraying her vitality and strength.

Thanks to Frida’s photographic collection, we can now state that her father’s fascination for self-portraits was a fundamental influence on both, the artist’s work and the way she always posed for the camera. Even in the childhood portraits taken by her father we can sense Frida’s astonishing talent for exploiting her best angles and poses.

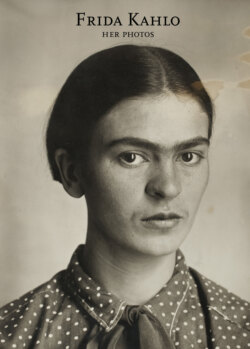

A piercing frontal stare, always focused on the objective, was the look Frida would always sport, both in her paintings and in the pictures taken by the greatest photographers of the 20th century―Imogen Cunningham, Bernard Silberstein, Lucienne Bloch, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Gisèle Freund, Fritz Henle, Leo Matiz, Guillermo Zamora, and Héctor García, among others. Many of these images were published at the request of Claudia Madrazo in the book La cámara seducida (The seduced camera, published by Editorial La Vaca Independiente), in 1992. Similarly, the exhibition Frida Kahlo, la gran ocultadora (Frida Kahlo, the Great Pretender, 2006–2007), presented in Spain and London at the National Portrait Gallery, showed over 50 original photographs, most of which were the only surviving copies. They were part of a collection belonging to Spencer Throckmorton, an American art dealer, who has collected many of Frida’s pictures over the years. To a great extent, the artist’s self-made character is owed to the great influence that photography exerted on her.

Even if once she said that she was a painter rather than a photographer, Frida, like her father, knew and handled the principles of photographic composition with great dexterity. She even experimented with the camera, as is witnessed by the images found in the Casa Azul archives. She is the author of three pieces, which she also signed in 1929. Nevertheless, there are many more that remain anonymous, but which can be attributed to her given certain features shared by her paintings. One of the pictures signed by Frida is a portrait of Carlos Veraza, the painter’s favorite nephew. The other two photographs are undeniably thought-provoking. The first one is reminiscent of Frida’s traffic accident at the age of 18, which would become the core obsession in her pictorial work. The piece shows a rag doll lying on a mat, next to a riding horse and a wooden cart at the side. The second appears as a very modern still nature where the objects may have been set out to be photographed in the fashion of modernist compositions by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Tina Modotti, or Edward Weston.

The stack of unsigned photographs includes one that stands out for its evident visual intention. It is a provocative image showing a huge cardboard-and-wire skeleton lying on a lawn.

The artist’s interest in photographic technicalities becomes evident in a letter from Tina Modotti containing instructions for Frida. Modotti answers Frida’s questions regarding certain aspects she would need to take into account in order to copy three negatives of Diego’s mural in Chapingo. “I have just received your questions, and I’m answering right away because I can imagine how difficult it must be for you to make the copies. Had I known you would make them yourself, I would have given you some personal directions […] I should say only one thing. Pan-chromatic film must be developed in a green light, not red, since red is the most sensitive color on this kind of film.”

On the other hand, and putting aside the technicalities of photography, this artistic means reflected Frida’s love and devotion. The artist altered some of her portraits and colored certain images or reproductions of her work, as is evident a photograph of her painting Self-portrait in a Velvet Suit (1926), which she lovingly called “the Boticelli.” This was a canvas painting dedicated to her first flame, Alejandro Gómez Arias.

In some other cases, Frida would cut out, fold away, or even tear up the photographs after being involved in conflicts with their subjects. And so happened with Carlos Chávez, who, as Director of the Institute of Fine Arts, refused to display Diego Rivera’s mural A Nightmare of War, A Dream of Peace (1952). This compelled Frida to send him an aggressive letter of rebuke and to banish him from her private album. Another example is the artist’s portrait with Lupe Marín, Diego’s second wife, which Frida carefully folded in two, thus detaching herself from the muralist’s ex-wife. It may be thought that Frida half-displayed the picture, hiding Lupe’s image yet keeping from destroying it, as she did in the case of Carlos Chávez’s picture.

Frida’s illnesses prevented her from spending much time outside and from entertaining her models for long periods of time. This is why she would use photographs to portray the characters on her canvases. In the Casa Azul archives were found, among many other examples, pictures of Stalin, which she would use for her unfinished painting Frida and Stalin (1954) and for Marxism Shall Cure the Sick (1954); portraits of Nickolas Muray’s daughter, which she would also use in one of her paintings; family pictures, on which she based the genealogy tree in Family Portrait (ca. 1950); photographs of her physician and friend Leo Eloesser; images of her pets, which she would portray in The Little Doe or Wounded Deer (1946); and several self-portraits with her parrot, her xoloescuintle dog, or Fulang Chang, her monkey.

Frida replicated in her paintings some photographs that would prove especially shocking or moving for her. Such is the case of a portrait featuring a small child lying dead on a mat, which she would then reproduce on canvas in Dimas Rosas, a Deceased Little Child (1937). Frida even used photographic fragments in some of her paintings, such as My Dress Hangs There (1933), where she accurately reproduces the image of the photographed crowd.

The great variety of photographs in this archive also accounts for the intellectual restlessness of a woman interested in topics ranging from biology and medicine to science and history, and particularly, art history. Frida utilized photography to put together a series of images she found in books and magazines, which she would later on re-use in her paintings. Those she obtained from gynecology books to illustrate female anatomy and childbirth are also decidedly outstanding.

The photographs in this book―a brief display of the thousands that Frida treasured―bear witness to the multiple purposes that the artist put them to. They are objects that throw new light on Frida Kahlo’s work. These images pave the way to the understanding of social life in the Casa Azul and also provide information on the personality and intelligence of one of the most renowned artists of recent times.

✭