Читать книгу Frida Kahlo. Her photos - Pablo Ortiz Monasterio - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

I. A Hidden Photographic Archive

There are in Frida’s archive over six thousand photographs. They have lain locked in wardrobes and drawers, next to drawings, letters, dresses, medicine bottles, and many other things. When Frida died in 1954 Diego Rivera decided to donate the Casa Azul to the people of Mexico so it would be converted into a Museum celebrating Frida’s work. He asked poet Carlos Pellicer―a friend of the couple’s―to design the project, and also selected some of Frida’s paintings, including an unfinished one, a portrait of Stalin. He left the portrait in the studio where Frida used to work: It was placed on her easel, beside her paintbrushes and paints. He also picked out some of her sketches, hand-made pottery, her votive offerings, a painted girdle, books, some photographs, documents, and various objects. He put the rest away. The mythical bathroom in the Casa Azul was bound to become the most important art repository in Coyoacán and its sur- roundings. Years later, Diego Rivera would legalize his gift to the people of Mexico, including the Casa Azul and the Anahuacalli, a massive structure built on and out of volcanic rock and designed by Diego himself to house his collection of pre-Hispanic “dolls.”

Shortly before his death, Diego asked his friend and executor Lola Olmedo not to open his personal archive before 15 years had passed. When the time came to do it, Lola decided that, if it wasn’t her friend Diego’s wish to open it, she wouldn’t do it either. So, the treasure was secluded for fifty long years. It remained asleep, like in La bella durmiente story, waiting to be given the breath of life. The enormously talented and industrious Hilda Trujillo, the museum’s current director, finally breathed new life into it.

This archive is the result of Frida’s tenacity―she put it together, worked on it, and enjoyed it over the years. It contains Frida’s photographs as well as many other pictures that she kept for Diego. It clearly reflects the interests that Frida nurtured over the course of her tormented life: Her family, her fascination for Diego and other flames, her wrecked body and medical science, her friends and several foes, her art and political struggle, her images of Indians and Mexico’s pre-Hispanic past. All of these were amassed with Frida’s burning passion for Mexico and everything Mexican.

From childhood, Frida was close to photography. Her father, Guillermo Kahlo, a German-born photographer, used to carry around a huge camera with delicate negative-film glass plates to shoot Mexico’s Colonial architecture. He did this with such precision and elegance that President Porfirio Díaz even commissioned him to photographically record Mexico’s cultural heritage. As part of the celebrations for the centennial anniversary of the Mexican independence in 1910, a photography book with Kahlo’s shots would be published. Due to her father’s occupation, little Frida became familiarized with photographic techniques and the basic principles of photo compositions. Guillermo’s daughters would assist him in the dark room, touching up photographic plates with delicate brush strokes and also occasionally accompanying him to take the pictures.

Frida treasured some of the pictures belonging to her maternal family as well as some of the pictures that her father had brought from Germany. Of course, she also kept those pictures her father made of her, her mother, her sisters, and her close friends. From this set, what stands out is the series of self-portraits that Frida’s father made from a very young age and over the course of his whole life. Mr. Kahlo cultivated the self-portrait genre, which would turn into a fundamental expressive tool for Frida ―her unibrowed face would soon be transformed into a looking glass where her esthetic, political, and vital concerns were mirrored. In the set of photographs pertaining to Matilde Calderón, Frida’s mother, we can immediately see where the artist’s taste and style of dressing came from. It should be said it was precisely this trait that made Frida famous―in certain circles she was better known for her garments than for her paintings.

II. To Keep Them Close

With the invention of photography in the early 20th century, the access to images was massively popularized. Common people could have their pictures taken and kept on surfaces coated with silver emulsions. These were likenesses that reproduced their physical appearance with uncanny precision. Years later, in 1854, A. Disdéri patented in France the carte de visite, an innovative system with which eight little pictures could be printed onto a single plate. It was then that the habit of exchanging photographs was born. Frida and Diego eagerly shared in this habit, an already old practice at the time. They would exchange and collect photographs of close friends and famous personalities whom they either admired or reviled, like Porfirio Díaz and Zapata, Lenin and Stalin, Dolores del Río and Henry Ford, André Breton and Marcel Duchamp, José Clemente Orozco and Mardonio Magaña, El Indio Fernández and Pita Amor, Nickolas Muray and Georgia O’Keeffe, among many others.

Many letters written by Frida betray an interest in the pictures of friends and acquaintances. As she used to say, their photographs served to “keep them close” and so maybe eschew loneliness. She also used her photographs as models. In 1927 she wrote the following to Alejandro Gómez Arias, an old flame from her teenage days: “[…] Next Sunday my dad will take my picture with ‘cañita’ so I can send you its effigy, huh? If you can have a nice picture taken, please send it to me one day so I can paint you a portrait when I feel a tad better.”

She wrote to Ms. Rockefeller from Detroit, in 1933, “[…] I can’t begin to thank you for the wonderful pictures of the children that you sent me […] I can’t forget the sweet face of Nelson’s baby, and the picture you sent me is now hanging on my bedroom wall.”

III. Reaching Eternity through the Instant

The first half of the 20th century was an extreme period. Revolutions were made and world wars were waged. Radical artistic movements arose and surprising vanguards sprang up. Photography took on a decisive role in culture as a means of communication and artistic expression.

Frida Kahlo was befriended and photographed by some of the greatest artists of the time: Nickolas Muray, Martin Munkácsi, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Fritz Henle, Gisèle Freund, Edward Weston, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Pierre Verger, Juan Guzmán, and a long etcetera. Her archive includes works by these artists and many more. These are not really pictures of Frida taken by them, but rather outstanding photographs of their authorship on various subjects. Paradoxically, Frida’s portraits do not abound in this lavish collection. It is not difficult to think, therefore, that she would repay her friends’ photographical gifts by sending them her own pictures. However, the set does contain the photographs that Frida gave to Diego. The formidable portrait that Martin Munkácsi took of Frida and Diego’s faces for Life magazine―a close-up―is not included here; nevertheless, there is the hissing black cat that Frida painted in Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Humming Bird in 1940, as well as the famous photograph of a motorcyclist riding through a puddle, two emblematic images by Hungarian master Martin Munkácsi. Referring to a picture by Munkácsi, Henri Cartier-Bresson remarked, “[…] with his work he made me understand that a photograph could reach eternity through the instant.”

Many pictures in this archive have inscriptions on them―names and dates that, on occasion, have been crossed out and rewritten, as those on photographs corresponding to Frida as a child. When, as an adult, the artist decided she would take three years off her real age, she altered the dates on some of these images to serve her rejuvenating purposes. Among these documents there are also notes, invoices, and lipstick stains in the shape of Frida’s lips, which add to the papers’ amorous undertones.

There is a tiny photograph, a very intimate one, of old Guillermo, her father, sitting down with a sad stare on his face. It reads on the front, “Herr Kahlo after crying.” In using the German word herr―which the dictionary translates as sir, master, boss, gentleman―to address her “dear dady” [sic], Frida describes the mood crudely and somewhat ironically. She hints at the strategy she would often resort to in order to face pain ―either her own or other people’s―; it is as if by bluntly naming, writing, or painting things the artist would be able to chase away the pain, or at least make it more tolerable. Ida Rodríguez hit Fridian home when she wrote, “[…] it is truth told in such a way that it seems a lie.”

When we analyze Herr Kahlo’s photograph―or that of Frida with her head leaning on the back of a couch and a vacant stare on her face―we can imagine the difficult times that the Kahlos went through in their lives. Frida gathered and kept visual testimony of that suffering, and maybe it was even she who proposed taking photographs so that she could look at them directly, name them and perhaps recycle them through her art. Physical pain and suffering were for her artistic incentives. Irony, beauty, and passion were tools for personal expression, while painful autobiography was the basis of her whole life. It had to be painted, photographed or written as it was―utterly beautiful and crude.

IV. The Painter Takes Pictures

Frida’s interest in photography arose early in her life, inspired maybe by the love and admiration she felt for her father. Frida’s close, endearing relationship with Guillermo becomes evident in the letter he wrote to Frida while she was in Detroit in 1932 “[…] your grateful father greets you and loves you very much as you know, right? Even if the others get a bit jealous.” Months later, Frida wrote on the back of a picture she sent back to her father: “Dear dady, here’s your Friducha so you can put her on top of your desk and never forget her.”

There was always a camera in Frida’s house so that important moments, picturesque places, and gatherings with friends, animals, and acquaintances could all be recorded. If Frida was interested, these characters and objects would be used as models for her paintings. There are the portraits of Griselda, her niece, with Hail, the little doe they kept for a while in the Casa Azul. Attributed to Nickolas Muray, these images may have been of great help to Frida when she painted the emblematic picture The Little Doe in 1946.

Hayden Herrera wrote for Frida’s 1985 exhibition in Spain,

Besides the dolls, which she avidly collected, Frida found other substitutes for children―her many animals, for example. In her self-portraits, her most faithful companions were monkeys. Even if their ape-like features betray a tongue-in-cheek resemblance to her own―and seem to console her―, what they really do is highlight her loneliness. The monkeys’ mobility does nothing but intensify the explosive energy that viewers can sense under Frida’s skin. These monkeys do not fill her life; instead, they point at the gaping holes there are in it.

One of the great surprises in this archive is the four 1929 photographs signed by Frida Kahlo. In 1929 Frida married Diego and traveled to the United States. It was a pivotal year in their lives. Frida surely took many more pictures, like the low-angle shot of a New York building, or the Judas skeleton lying on its flank, which served as a model for her 1940 painting The Dream. We cannot be sure whether Frida herself took those pictures, but we can certainly assure that many of these images relate to her paintings. Even if she did not take them herself, she did recycle them in her work. The photographs she decided to sign are a portrait and two still natures (objects arranged to be photographed), modeled on Modernist compositions by Edward Weston, Tina Modotti, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and Agustín Jiménez. There is a fourth picture we know Frida did take ―the photograph of a dog. On the back, Frida wrote to Diego, “Little brother: She is a bit sad because she was asleep and I woke her up, but she says she was dreaming that Diego would come back soon. What do you say? I’m sending you lots of kisses, and also la Chaparra.” The picture of the rag doll and the horse cart on the mat―apart from being overtly modernist―boasts Frida’s signature, one that appears in almost all of her works, whether they be paintings, sketches, texts, and now photographs too. These pictures represent, on the one hand, the narrative tendency to put forward the traumatic events she went through and, on the other, her obsession with her broken, handicapped body.

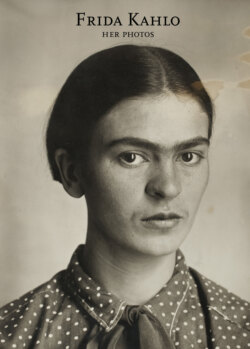

The camera was always familiar to Frida Kahlo. She seems to have felt comfortable in front of it. She even learnt to look into the lens to put across what she wanted and managed to reinvent her own image through photography. I like to think that the stack of photographic portraits in which Frida’s life is recorded constitutes another one of her masterpieces. The painter once wrote about her strategy in front of the camera. “I knew that the battlefield of suffering was reflected in my eyes. Ever since then, I started looking straight into the lens, without winking, without smiling, determined to prove I would be a good warrior until the end.”

V. The Broken Body

Frida Kahlo embodies both Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalsky, played by Vivian Leigh and Marlon Brando in the film A Streetcar Named Desire by Elia Kazan. She is fragile and pathetic like Blanche DuBois yet strong and seductive like Stanley Kowalsky. She is herself a streetcar named desire, wrecked in an accident.

In a 1946 letter addressed to engineer Eduardo Morillo, Frida wrote about the painting Tree of Hope, Stand Firm,

I’m almost finished with your first painting, which, of course, is but the result of the damned surgery! It’s me―sitting on the brink of a precipice―holding the steel girdle in one hand. Behind that, I’m lying on a hospital gurney―with my face turned to a landscape―, a small part of my back uncovered, where you can see the scars from the surgeons’ stabs. “Darn SOB’s!” It’s a daytime and nighttime landscape, and there is a “skeletor” (or death) running away from my strong will to live.

In the archive that Frida so zealously kept there is a series of black and white shots showing the painter on her bed. She used them as references to paint engineer Morillo’s picture. It can be sensed in them that Frida lived a good part of her life lying on that bed―it was there that she would paint, socialize, speak on bulky Ericsson phones, laugh, cry, eat, dream, and above all, suffered long and intense pain. Carlos Monsiváis summarizes this in plain words when he says, “In Frida Kahlo’s development there is not only an artistic and cultural improvement that allowed her to exploit her vast talent, her intense relationships with various people, and a strong sense of sensible refinement. There is also, and very essentially, a letting go resulting from incontrollable suffering and the contemplation of reality through pain.” A detailed study of this archive will certainly produce new versions of the legendary painter from Coyoacán. This is why we are ready to offer you this collection of photographs where Frida’s voice can be heard. It seems to whisper, “Long live life!”

✭