Читать книгу The South West Coast Path - Paddy Dillon - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

A rocky coastline and contorted cliffs are seen from the Hartland Quay Hotel (Stage 8)

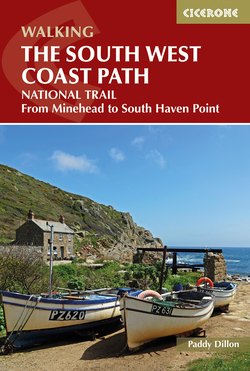

The South West Coast Path is the longest of Britain’s National Trails, measuring a staggering 1014km (630 miles). It is not just a long walk, but an astounding and varied experience. This remarkable coastal trail is based on the paths trodden around cliffs and coves by generations of coastguards. The route starts in Minehead on the Somerset coast and quickly moves along the North Devon coast. After completely encircling the coast of Cornwall, it runs along the South Devon coast. A final stretch along the Dorset coast leads to a conclusion at South Haven Point on Poole Harbour. No other stretch of British coastline compares for scenic splendour, interest, history, heritage, accessibility and provision of facilities all rolled into one.

A fit and dedicated long-distance walker would take a month to walk the South West Coast Path. The current record, set by Damian Hall in May 2016, stands at 10 days 15 hours 18 minutes. Others are happy to enjoy the experience, savour the delights of the trail, and take two months or more to cover the distance. Hardy backpackers happily carry a tent, sleeping bag and cooking equipment, while others prefer to mix youth hostels with B&B accommodation. Some walkers prefer a luxurious approach, staying in splendid hotels while sampling local seafood menus. The South West Coast Path appeals to all types, but remember that many facilities are only open through the summer season.

Cosy fishing harbours abound, but many locals now work in tourism instead

Individual approaches vary. Some walkers crave to cover the whole trail in a single expedition, while others take a weekend here and there, and make an occasional week-long trip, to complete the distance over a year or two. You must walk within your limitations, covering distances that are comfortable for you, choosing accommodation that suits your tastes and pocket. Allow time to visit museums and heritage centres, if you have a passion for local history, or to observe birds along the cliff coasts if you are interested in wildlife. Given the nature and complexity of the coast, it makes sense not to rush, but to enjoy the experience.

PLANNING YOUR TRIP

Itineraries

Almost every town and village offers some refreshment (Cadgwith on Stage 23)

While some might be daunted at the prospect of walking for weeks on end, staying somewhere different every night, while keeping themselves fed and watered, it is simply a matter of careful planning. Almost every town and village along the way offers some kind of accommodation and refreshment, but it’s always useful to know what’s available in advance.

This guidebook describes the whole trail from Minehead to Poole Harbour, indicating the level of services along the way. The route is well marked with ‘Coast Path’ signposts and standard National Trail ‘acorn’ symbols. Read each section before setting out. You might, for example, need to ensure that ferries are running across awkward tidal rivers, or secure accommodation in advance in summer, or you might like to know if the next sandy cove has a beach café. Break the route into manageable sections to suit your own ability. There’s no need to stick slavishly to the daily breakdown given in this book, as there are usually plenty of intermediate places where you can halt.

The suggested itinerary covers 45 days, and while the author has comfortably completed the Coast Path by following this plan, he first covered the distance in only 28 days. The South West Coast Path Association, however, present a 70-day itinerary. If three achievable itineraries were offered for tough, average and easy-going walkers, they might cover 35, 45 and 65 days. It’s unlikely that any walker would follow a set schedule, and almost everyone will choose a comfortable distance each day, taking into account whether the next stretch is easy or difficult, bearing in mind a good or bad weather forecast, coupled with an assessment of how well they feel.

You can allow more days by splitting some of the longer stages into two days, or you can double up a couple of stages, albeit at the risk of fatigue. The daily average in this guidebook is 22.5km (14 miles), generally in the range from 18–28km (11½–17½ miles). The longest day is 37.5km (23¼ miles) but this is mostly easy and level, and it can be shortened or split into two if desired. The shortest day is 12.5km (7¾ miles), which happens to be the last one. Alter and adapt the schedule to suit your own needs and preferences, aiming for something that doesn’t leave you wrecked!

The daily stages are not only of uneven length, but some days are fairly easy and others are quite difficult. Read each day’s description carefully before committing yourself, taking note of steep ascents or descents, seasonal ferries, absence of food, drink and accommodation, or anything else that might affect your rate of progress. Keep an eye on the weather forecast and tide tables (see Appendix A for useful websites). Sometimes you might be walking into driving rain, which can be debilitating. Strong winds on clifftops can be very dangerous. Prolonged wet weather makes paths muddy and slippery. Long vegetation might be a problem in a few places in late spring, but it is usually cut back through the summer.

The beach at Swanage, looking towards the final chalk headland on the Coast Path (Stage 45)

Despite all your planning, you may find yourself running out of time towards the end. If you’re only short of one or two days, you could skip the one-day circuit round the Isle of Portland (regrettably, because it’s an excellent walk) but still feel that you were staying faithful to the coast. There’s also the South Dorset Ridgeway, inland across the downs, enabling you to keep an eye on the sea while omitting Weymouth and the Isle of Portland altogether. It might give you the time you need to reach the end of the Coast Path on time. Other shortcuts may smack of ‘cheating’, but at the end of the day it’s your walk and your walk alone!

When to go

For many, the biggest hurdle is finding the time to complete the whole of the South West Coast Path in a single trek. You need to be able to put your home life on hold for several weeks, maybe taking leave of absence from work, or waiting until you retire! Are you serious about completing the whole trail, and are you equal to the task? It might be better to spread the journey over three or four trips of a fortnight or so, judiciously planned to give a taste of all four seasons on the Coast Path. At the end of the day it’s your walk to be completed however you see fit.

All services along the South West Coast Path are in full swing during July and August, but that can be a stressful time to walk. Days can be hot and humid; crowds of people mill around the towns and villages; while accommodation for one night can prove difficult to obtain. Walking in May and June or September and October can be cooler without being too cold and wet. Crowds will be much reduced, although some areas will be busy. Accommodation is easier to obtain, while most places offering food and drink remain open. However, not everything will be open, and some beach cafés may be closed early or late in the season. Check that the smaller seasonal ferries are going to be operating.

Parasols at the Life’s a Beach café at Maenporth, on the way to Falmouth (Stage 24)

Walkers who attempt the South West Coast Path from late October to early April must expect many places to be closed, and some ferries to be absent. Winter weather can be milder than in other parts of Britain, with snowfall rare, but it can still be cold and wet. Winter gales can be ferocious! Some places may flare into life over the Easter period, but close immediately afterwards. Winter walkers need their wits about them to be able to complete the trail successfully. The Coast Path was damaged at several points during the winters of 2011, 2012 and 2013, with more damage early in 2014. Funding had to be secured for a programme of repair works to take place in 2015.

Travel to the South West

By air

The main regional airports are Bristol, www.bristolairport.co.uk, and Exeter, www.exeter-airport.co.uk. Although these are a fair distance from the start of the Coast Path, they may suit those who have to travel from the furthest reaches of Britain, or who are coming from overseas. Other useful small airports are located at Newquay, www.cornwallairportnewquay.com, Land’s End, www.landsendairport.co.uk and Bournemouth, www.bournemouthairport.com.

By train

CrossCountry Trains, www.crosscountrytrains.co.uk, run from Scotland, through Northern England and the Midlands to feed into the South West of England. Trains can be used to reach Taunton, from where there are regular buses to Minehead. If walking the Coast Path in stages, the same train runs all the way to Penzance. CrossCountry Trains also run from Poole and Bournemouth to Scotland. Great Western Railway trains, www.gwr.com, run from London Paddington to Penzance via Taunton, and the company also serves branch lines to Barnstaple, Newquay, St Ives, Falmouth, Looe, Torquay, Exmouth and Weymouth. Other main line services include South Western Railway, www.southwesternrailway.com, from London Waterloo to Exeter, Bournemouth and Weymouth.

By bus

Most towns have National Express offices or agents, and most tourist information centres have details of services. National Express buses serve a number of towns, including Taunton, Barnstaple, Bideford, Westward Ho!, Newquay, Perranporth, Hayle, St Ives, Penzance, Falmouth, St Austell, Plymouth, Brixton, Paignton, Torquay, Teignmouth, Dawlish, Bridport, Weymouth, Swanage, Poole and Bournemouth. There are some useful long-haul services to the South West; these include Edinburgh/Glasgow to Penzance, Newcastle to Plymouth, Grimsby to Westward Ho!, Liverpool to Weymouth, Eastbourne to Falmouth, and services from London to places such as Swanage, Plymouth, Newquay and Penzance. Bear in mind that there are seasonal variations on some services. Visit a National Express agent or tel 0871 7818181, www.nationalexpress.com.

Travel around the South West

By train

Rail services in the South West consist of a main line and branch lines, with Great Western Railway, www.gwr.com, being the main local operator. The West Somerset Railway offers seasonal steam-hauled services to Minehead, but doesn’t connect with main line services at Taunton, although there are bus links. The only coastal railway station in North Devon is at Barnstaple. Coastal stations around Cornwall include Newquay, Hayle, St Ives, Penzance, Falmouth, Par and Looe. Stations on the South Devon coast include Plymouth, the Dartmouth Steam Railway, then Torquay, Teignmouth, Dawlish, Dawlish Warren, Starcross and Exmouth. Stations on the Dorset coast include Weymouth, Poole and Bournemouth. Steam-hauled services at Swanage do not connect with the rest of the railway network.

Waves beat against the sea wall supporting the railway line beyond Dawlish (Stage 37)

By bus

Walkers who plan to break their journey and cover the South West Coast Path in several stages may need to use local bus services. With careful reference to timetables, walkers could choose handy bases and ‘commute’ to and from sections of the Coast Path. Most bus services in the South West are operated by the First bus company, www.firstgroup.com, although there are other operators.

The two most important services are the regular buses from Taunton station to Minehead, before starting the walk, and from Sandbanks to Poole or Bournemouth at the finish. Throughout this guidebook, places with bus services are mentioned, with some indication of connections along the coast, but do enquire further for specific timetable information, as this is often subject to change, and some areas are only served by buses during the peak summer season.

Ferries

The South West Coast Path is broken into a number of stretches by several long, narrow, tidal rivers, especially on the southern stages. Ferries have to be used to cross these rivers, and as these are part of the South West Coast Path experience it shouldn’t be seen as ‘cheating’. If the urge seizes you, it is possible to walk around the estuaries, but this leads well away from the coast and may take several hours – or even days – to reach a point that can be gained by a ferry in mere minutes.

Be warned that while some ferries operate all year, others are seasonal or irregular, or are subject to tidal and weather conditions. In the peak summer months of June, July and August, all ferries will be operational. Others may run from May to September, or Easter to October. Winter walkers will find some ferries absent. In this guidebook, contact numbers are given for the ferries, with some indication of the level of service you can expect. For regular, all-year-round ferries, it is sufficient to turn up and catch one on a whim, but smaller, less regular ferries should be checked in advance or your walk may grind to a halt on a lonely shore.

See Appendix A for the contact details of ferry operators along the South West Coast Path, given in the order in which you will encounter the crossings as you walk the route from start to finish.

A ferry is used to cross the mouth of the River Fowey to reach Polruan (Stage 28)

Traveline

Check the timetables of any local train, bus or ferry through Traveline, tel 0871 2002233, www.traveline.info. It is also possible to use Google Maps ‘directions’ to search for public transport. Simply enter your start and finish points and hit the ‘bus’ symbol to be given the next available service and corrections. Use ‘options’ to change the time and date to search for later services.

Accommodation en route

Sarah Ward’s Minehead marker at the start of the path

There is abundant accommodation around the South West Coast Path, but think carefully a day or two in advance to ensure you have a roof over your head. There are long and difficult stretches of coast that seem remote from habitation, and some places where lodgings are restricted to only one or two addresses. Even in the big towns, it can be difficult to obtain a bed for the night in the peak season. Check the online database at Luggage Transfers, www.luggagetransfers.co.uk, which lists almost a thousand addresses around the South West Coast Path, and see Appendix B for an overview of what’s available along the way.

Backpacking

If you’re prepared to carry all your gear, backpacking is a great option. You can walk with a high degree of freedom: setting off at dawn, walking until dusk, generally pleasing yourself. To locate campsites, there are several marked on OS maps, but there may be many others. It’s well worth packing as light as possible, and there’s no need to carry several days’ supply of food as there are ample opportunities to restock.

Some campsites are geared for long stays or for large family tents, rather than one-night backpackers with small tents. Some walkers camp wild, unobtrusively, leaving no evidence of their overnight stay, but this is technically illegal and permission should be sought from the landowner. Ask politely for permission to camp, and offer to pay, or risk eviction for not asking! The Backpackers Club, www.backpackersclub.co.uk, offers a members-only list of over 200 Coast Path campsites and suggests wild camp locations.

Hostelling

There are 15 YHA hostels within easy walking distance of the Coast Path. However, there aren’t enough to be able to walk from one to the other without falling back on other types of accommodation. YHA hostels are marked on OS maps and full details can be checked at www.yha.org.uk. There are also around a dozen independent hostels that might prove useful, www.independenthostels.co.uk. Hostellers may need to carry a tent if they wish to walk within a low budget, or fall back on low-cost B&B accommodation to fill gaps along the way.

Tintagel Youth Hostel enjoys a fine outlook from its cliff-top situation (Stage 11)

Bed and breakfast

Walkers who want to travel lightweight and enjoy a bit of luxury can use B&Bs, guest houses and hotels. These are available at regular intervals, although in irregular concentrations. Not every establishment wants to have one person staying for one night only, and many prefer to have couples staying for a weekend or week-long periods. However, when there are cancellations at busy periods, they’ll take anyone! Some accommodation providers deal well with walkers, and may be prepared to offer pick-ups and drop-offs, packed lunches, or arrange to move luggage onwards, but there is usually a charge for such extra services.

Block bookings

If you book all your accommodation for the duration of your long trek in advance, you may regret it later. Bad weather, fatigue or injury can prevent you from covering the distance to your next lodging, and trying to unwind arrangements and re-book at short notice can become a nightmare. Outside the peak summer season it should be possible to book two or three days ahead, then book another night or two later, based around your performance on the trail. If assistance is needed, it’s always possible to deal with Luggage Transfers, www.luggagetransfers.co.uk, and let them make the arrangements. Walkers recommend many of these addresses, so there’s a good chance you’ll be very well looked after.

Book a bed ahead

A few tourist information centres can make bookings for you, and they usually have a good knowledge of what’s available in their localities. They may also be able to book places two or three days ahead along the trail. Let them have your requirements, then retire for a cream tea and pop back after half an hour to see how they’ve fared. They typically make a small charge for these services, and they may also charge a deposit, which will be discounted from the bill you pay at your accommodation.

Facilities en route

Looking back to Portloe and its tiny harbour from the cliff path (Stage 26)

Food and drink

In the peak summer season there’s no shortage of food and drink along the South West Coast Path. In fact, backpackers often regret carrying cooking equipment as they walk past frequent offers of pasties, chips and cream teas. All the towns have an abundance of pubs and restaurants, and many small villages may have a couple of pubs and cafés. However, it’s always good to know which villages don’t have these services, as well as which beaches are likely to have a café.

Throughout this guidebook, pubs, restaurants, cafés and shops are noted in passing, and Appendix B provides an at-a-glance breakdown of what’s available on and near the route. Bear in mind that in the winter months many places close. Refreshments can seem grossly overpriced at some places, but remember that you’re paying for the convenience, and taking your custom elsewhere could result in half a day’s walk!

Money

Being away from home for weeks, you either need to carry lots of money, or need access to funds along the way. Many upmarket accommodation providers and restaurants will accept credit cards, but most other places want cash. There are banks at irregular intervals, and most have ATMs (see Appendix B). Banks in towns along the way are noted in this guidebook. Post offices are also mentioned, which could be useful as they offer banking services. Some supermarkets may have a cash dispenser in-store, or they may offer a ‘cashback’ service.

A seven-week backpacking tour might just be completed on a budget of a few hundred pounds, while seven weeks of staying in hotels and eating splendid meals might easily run to several thousand pounds!

A homeless couple walked the path on an extremely tight budget. Read The Salt Path by Raynor Winn, published by Michael Joseph.

Tourist information centres

There are about 40 tourist information centres either on the Coast Path or a short distance from it. They contain a wealth of local information and the staff are usually very knowledgeable. Most of them will be able to assist with local accommodation bookings. Details are given for tourist information centres on the Coast Path, both as they occur along the route and in Appendix A.

Baggage transfer services

More and more long-distance walkers take advantage of luggage transfer services these days, and one company covers the whole of the South West Coast Path. Luggage Transfers (tel 0800 043 7927, www.luggagetransfers.co.uk) will collect and transfer luggage between overnight stops, leaving you free to carry only a day sack along the Coast Path. In some instances they will also transport people. Transfers need to be arranged at least a day in advance, so check their terms and conditions, bearing in mind that accommodation and campsite bookings may need to be confirmed before they will undertake to deliver.

One man and his dog

Maybe you were inspired by 500 Mile Walkies, by Mark Wallington, who took his dog Boogie around the South West Coast Path, or maybe your dog always goes with you on long walks. Note that many beaches have a ‘dog ban’ during the summer months, and there are many fields near cliff edges where sheep and cattle graze, where a dog might cause a stampede. If cattle react aggressively to your dog, let it off the lead and ensure your own safety. Your dog will usually manage fine on its own and will rejoin you later. People have been killed while trying to protect their dogs.

Local people walk their dogs along daily beats, and some local dogs resent the approach of a strange dog. Walkers with dogs will find that some accommodation providers won’t accept them, and some pubs and restaurants won’t allow dogs on the premises. Think carefully before committing yourself to such a long walk with man’s best friend.

What to take

Walkers heading towards Damehole Point between Hartland Point and Hartland Quay (Stage 8)

Kit choice depends largely on choice of accommodation and whether or not luggage transfers are to be used. However, no special kit is required for walking along the South West Coast Path, apart from decent footwear, waterproofs for wet and windy days, and a sunhat and sunscreen for hot and sunny days.

Completely self-sufficient backpackers should travel lightweight, and will not need particularly robust tents or bulky sleeping bags in summer. Food and drink can be bought at regular intervals, so there is no need to carry heavy loads.

Those who plan to sleep indoors could manage with nothing more than their usual day-sack contents, plus a change of clothes and possibly a lightweight change of footwear. However, this assumes that clothes will be washed and dried every couple of days, and walking with such a lightweight pack will of course mean sacrificing many luxuries.

Plenty of extra clothing and footwear, along with a variety of luxury items, can be packed if you’re using a luggage transfer service. Always ensure that the people at each accommodation stop are aware that your luggage will be left with them, and be realistic about the distance you intend to cover each day – or you may find yourself falling short of where your luggage has been delivered!

Whatever is being carried, be sure to check footwear, clothing and kit from time to time to ensure that nothing is failing or in need of replacement. A basic repair kit can take care of minor tears and stitch-work. Items of kit and clothing can be replaced in most large towns, but suddenly changing into new and unfamiliar footwear could be asking for trouble. In case of sudden need when far from a decent range of shops, it might be necessary to catch a bus or train off-route in search of particular items.

PLANNING DAY BY DAY

Godrevy Island and its lighthouse off the end of Godrevy Point (Stage 17)

Using this guide

An information box at the beginning of each stage provides the essential statistics for the day’s walk: start and finish points (including grid refs), distance covered, height gain, the length of time it’s likely to take to complete the stage, an overview of the types of terrain you’ll encounter, the appropriate OS Landranger and Explorer sheets along with the relevant A–Z atlas and Harvey map, and places en route (as well as slightly off-route) where you can buy refreshments.

Stage maps, extracted from the Ordnance Survey mapping, are provided at a scale of 1:50,000. They run from page to page, covering the whole of the South West Coast Path. In the route description, significant places or features along the way that also appear on the map extracts are highlighted in bold to aid navigation. As well as the route being described in detail, background information about places of interest is provided in brief. For help in decoding some of the local place names, see Appendix C.

Both Appendix A (Useful contacts) and Appendix B (Facilities along the route) provide details that may be useful in planning and enjoying a successful walk.

Maps and GPS

In print, a dozen OS 1:50,000 scale Landranger sheets cover the entire route: 180, 181, 190, 192, 193, 194, 195, 200, 201, 202, 203 and 204. The OS 1:25,000 scale Explorer Series covers the entire route in 16 sheets: 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 110, 111, 115, 116, 126, 139, OL9, OL15 and OL20.

Three Cicerone map booklets contain detailed 1:25,000 OS mapping of the South West Coast Path. They are: Vol 1 Minehead to St Ives; Vol 2 St Ives to Plymouth; Vol 3 Plymouth to Poole.

Harvey Maps, www.harveymaps.co.uk, covers the South West Coast Path in three waterproof sheets, at a scale of 1:40,000, as part of their National Trail series.

Increasingly, walkers are making use of mobile devices and navigation apps that combine GPS and OS mapping. While this saves considerable weight, users must ensure that their devices are regularly charged to be effective.

Time and tide

If the tide allows, it is worth going down to the beach at Bedruthan Steps (Stage 14)

The old proverb states that ‘time and tide wait for no man’, and this is true on the South West Coast Path. If planning a fairly rigid schedule along the route, then be sure to obtain up-to-date tide tables, which can be purchased at shops and tourist information offices. Tide times are often posted at RNLI lifeboat stations and lifeguard cabins, as well as at harbour offices. Do not walk along beaches at the foot of cliffs when there’s a danger of being cut off by the rising tide, and avoid wading across tidal channels if a ferry is available. The River Erme, which has no ferry, can cause considerable delays when walkers have to wait for low water.

Take careful note of any stretches of the route that run along beaches. High, pebbly storm beaches are likely to be safe most of the time, except, as their name suggests, during fearsome storms. Marshes tend to get covered by the highest tides, but are free of water at most other times. Lower-lying beaches, expansive sands and mudflats are subject to twice-daily inundation, which can bring progress to a halt. Usually, this might only be for an hour, but in some places it could be longer. If walking along beaches while the tide is rising, always ensure that you can escape inland if necessary.

The ‘Three Rocks’ are prominent red sandstone stacks at Ladram Bay (Stage 38)

Tides depend primarily on the position of the Moon relative to the Earth, centrifugal force, and to a lesser degree, the position of the Sun. Rather than trying to understand the astronomical and physical data, just refer to current tide tables, or check www.tidetimes.org.uk and bear in mind the following:

high water occurs in cycles approximately every 12 hours and 25 minutes

low water occurs in cycles approximately every 12 hours and 25 minutes

spring tides rise higher than neap tides and both occur about a week apart

tide tables are usually quoted in GMT, so add one hour for BST in summer

tide tables are actually tide ‘predictions’, so use the data provided carefully, and

strong onshore winds and low air pressure cause additional storm surges.

Looking at the above, beware of any beach walks that are likely to take place when tides are rising, and more particularly when spring tides are forecast. It’s best to avoid beach walks altogether when high tides are forecast to coincide with strong onshore gales. In recent winters, several stretches of the South West Coast Path were damaged, requiring substantial repairs during 2014 and 2015.

Waymarking and paths

The South West Coast Path is waymarked, but route-finding is still important

The South West Coast Path is a National Trail, so it’s well signposted and waymarked from start to finish. Signposts may simply state ‘Coast Path’, or waymark posts may carry nothing more than a direction arrow and an ‘acorn’ symbol. Some signposts will give destinations further along the trail, and may also indicate the distances to those places. In urban areas, where the route may turn left and right in quick succession through busy streets, there might be no signposts, or they may be lost among other distracting signs and notices. In some cases, metal ‘acorn’ discs might be set into the pavement, or ‘acorn’ stickers might be applied to lamp posts. It’s often the case that route-finding is more difficult in urban areas than it is on a remote stretch of coast!

The South West Coast Path is exceptionally well maintained, but a coastal trail of this length will always require attention somewhere along its course. In some cases, stretches that get overgrown will be cut back once or twice a year. Damage to signposts, stiles and footbridges won’t be attended to until someone reports them. If a problem is spotted, report it using the online facility on the South West Coast Path website (www.southwestcoastpath.org.uk), and in the author’s experience, they’ll probably respond within two days and tell you they fixed a minor problem!

Damage to the path itself may result in diversions, if it becomes dangerous to continue. Serious problems take longer to fix. Any detours put in place should be clearly marked, and information should be available on the website. Problems that can’t be fixed will result in permanent re-alignment of the route, so beware if using an old map or guidebook.

Rescue services

Rescue services can be alerted by dialling 999 (or the European emergency number 112) from any telephone. On some popular beaches there may be a phone dedicated as an emergency line. The coastguard service is able to coordinate assistance from the police, ambulance, fire service and lifeboat as necessary. You cannot call for a helicopter, but based on the information you provide, one of the emergency services may request a helicopter to assist. Always give as much information as possible, especially as to the location and nature of an accident, then await further instructions.

Walkers don’t often suffer accidents on the Coast Path, but it makes sense to walk with care near cliff edges and always be on the lookout for unstable edges, landslips and rockfalls. Tread carefully on steep and uneven paths. Always check the weather forecast and be aware that heavy rain or strong winds can make walking difficult or even dangerous.

Walkers who want to go swimming should read the warning notices posted at the most popular beaches, and check local conditions with lifeguards if they are present. In out-of-the-way places, don’t go swimming without a good understanding of the nature of the sea.

Nare Head, seen in the distance from a point before Pendower Beach (Stage 25)

Safety on the Coast Path

As well as following the Countryside Code, when you are walking the South West Coast Path, always remember to follow the advice provided on the official South West Coast Path website.

Staying safe is your own responsibility – look after yourself and other members of your group

Let someone know where you’re going and what time you’re likely to be back – mobile phone reception is patchy on the coast.

Take something to eat and drink.

Protect yourself from the sun – sea breezes can hide its strength.

Informal paths leading to beaches can be dangerous and are best avoided.

If you’re crossing a beach, make sure you know the tide times so you won’t be cut off.

Keep to the path and stay away from cliff edges – follow advisory signs and waymarks

Keep back from cliff edges – a slip or trip could be fatal.

Remember that some cliffs overhang or are unstable.

Take special care of children and dogs – look after them at all times

Keep your dog under close control.

Children and dogs may not see potential dangers – such as cliff edges – especially if they’re excited.

Do not disturb farm animals or wildlife – walk around cattle and not between them, especially if they have calves.

Cattle may react aggressively to dogs – if this happens, let your dog off the lead.

Dress sensibly for the terrain and weather – wear suitable clothing and footwear and be ready for possible changes in the weather

Check the weather forecast before you set out.

On the coast, mist, fog and high winds are more likely and can be especially dangerous.

Wear suitable footwear.

Take waterproofs and extra clothing, especially in cold weather.

Stay within your fitness level – some sections of the Coast Path can be strenuous and/or remote

Plan a walk that suits your fitness level.

Find out about the section you plan to walk.

Turn back if the walk is too strenuous for anyone in your group.

Be aware that the surface of the Coast Path varies and will generally be more natural and more uneven away from car parks, towns and villages.

Remember that in remote areas or at quiet times you may not see another person for some time if you are in difficulties.

In an emergency, dial 999 or 112 and ask for the coastguard

Learn to read a map to be able to accurately report your position – visit www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk

The ‘Rugged Alternative Coast Path’ runs closer to the sea than the main route (Stage 1)

South West Coast Path Challenge

A major fundraising event is organised each October along the Coast Path. The aim is to get as many walkers as possible, of all ages and ability, to choose and walk a stretch of the route. Funds raised are used to maintain the Coast Path, which is estimated to cost £1000 per mile per year. Full details of the challenge are available at www.southwestcoastpath.org.uk

ALL ABOUT THE REGION

Geography

Looking back towards the headland of Cambeak on the way towards Beeny Cliff (Stage 10)

The South West Coast Path is confined to the extreme south-western peninsula of Britain. The coastal scenery ranges from high cliffs and rugged slopes to long, sandy beaches and hummocky dunes, with some areas of marshland, as well as small settlements and larger urban areas. Inland, there might be anything from green fields and woodlands to rugged heather moorlands and masses of gorse bushes. However, the most elevated parts of the south-west lie much further inland, including Exmoor, Dartmoor and Bodmin Moor. The high ground interrupts winds carrying moist air from the Atlantic Ocean, resulting in more mist and rain at altitude than is experienced around the coastline.

Geology

The Coast Path passes through a notch in the crumbling granite of Cligga Head (Stage 16)

The south-west of England is a huge area, and its geology is not easily condensed into a few words. The oldest rocks are of late Cambrian age, from 490 million years ago, found on the Lizard peninsula in South Cornwall. They derive not from the earth’s crust, but from the deep-seated mantle beneath. They’ve undergone a process of metamorphosis – altered by immense temperature and pressure – and one of the most important rock-types resulting from this is serpentine, which is locally worked into delightful ornamental forms.

The bulk of rock types in Exmoor, Devon and Cornwall are of Devonian and Carboniferous age, stretching from 420 to 300 million years ago. Vast thicknesses of sediments were laid beneath the sea, becoming gritstone, sandstone, shale and limestone. Towards the end of this period, the rock beds were being squeezed into mountain ranges, becoming crushed and folded. A huge batholith of molten rock, deep in the Earth’s crust, pushed them upwards, solidifying to become the granite that is now exposed around Dartmoor, Bodmin Moor, St Austell, Carnmenellis and West Penwith. Coastal cliff faces often display intensely contorted beds of rock, best seen around Hartland and Crackington Haven in North Cornwall.

The heat and pressure associated with mountain-building also squeezed mineral-rich fluids into cracks in the rock, which solidified into metal-bearing veins containing tin, lead and copper, giving rise to an important mining industry. Some shales and mudstones were changed to slates, which were quarried as roofing material. Granite has been used extensively for building, as it is generally hardwearing. In places where it rots and crumbles, it provided the basic ingredient for the china-clay industry around St Austell.

The Permian, ranging from 300 to 250 million years ago, saw extensive desert landscapes, but this was followed by the Triassic, when the land sank back under the sea. The geology of east Devon and Dorset is remarkably different. The Triassic gave way to the Jurassic, from 200 to 145 million years ago, and the abundant marine life is preserved in fossil-rich locations along the coast. Further east, the Cretaceous, from 145 to 65 million years ago, is characterised by immense thicknesses of chalk, giving rise to sheer white cliffs. The ‘Jurassic Coast’ is a World Heritage Site on account of its geological significance.

During the last Ice Age the south-west was free of glaciers and the landscape was bleak tundra with permafrost conditions. Britain wasn’t an island, but was joined to mainland Europe. With the melting of the northern ice sheets, sea levels rose, but the whole of Britain tilted, with Scotland rising slightly, as evidenced by numerous raised beaches. The south-west of England, by contrast, sank so that river valleys were flooded by the sea. Along some parts of the coast the land is steadily being eroded, while on other parts of the coast the same eroded material is being piled up into beaches of sand and shingle.

Plants and wildlife

Sea pinks above Mill Bay, or Nanjizal, on the way from Land’s End to Gwennap Head (Stage 19)

Woodlands are uncommon along the Coast Path, with the greatest concentration occurring during the first week, through Exmoor and north Devon. Semi-natural woodland is rare, and most woods are actually plantations. There are plenty of trees in hedgerows, while in places exposed to wind and salt-burn, trees are often stunted and lean dramatically inland in formations known as ‘krumholz ’. The woody shrub called gorse generally blazes with yellow flowers in the summer. Non-native trees and bushes may be spotted along the coast, including ornamental palm trees in some resorts and gardens.

In many uncultivated places, there may be a rich coastal heath, comprising of stunted gorse scrub and heather, through which an abundance of wild flowers grow, well protected against grazing animals. More specialist plants cling to rocky cliffs, safe from grazing, or are able to flourish on dry storm beaches or perpetually wet mudflats. Attempting to list everything that might be seen on a trek as long as this is pointless, but plenty of species can be observed with reference to information boards at various points around the coast – particularly at nature reserves. Flowering coastal plants that should be spotted on a day-to-day basis include sea campion and sea pinks, also known as thrift.

A cow goes down to drink from the stream at rocky Porth Mear (Stage 14)

Walkers see a lot of farm livestock along the Coast Path, usually confined to fields but occasionally grazing on rugged coastal slopes or grassy saltmarshes. Expect to see plenty of sheep, rather fewer cows and occasional horses. Very rarely, feral goats might be spotted. Small mammals such as rabbits are common, while amphibians and reptiles tend to be furtive and are seldom spotted. Take note of path-side information boards that indicate species that might otherwise be missed. The sea teems with animal life, from shellfish to all kinds of fish, with the largest likely to be basking shark. There are colonies of seals and dolphins, but these are rarely spotted.

Birdwatchers will find hundreds of species to distract them along the Coast Path, and there are plenty of information boards along the trail highlighting what might be spotted. Bird hides are occasionally available, especially at nature reserves, or where the RSPB manage areas of the coast. In very general terms, many breeding species, residents and migrants can be observed rearing young during the summer. Overwintering wildfowl are likely to congregate on mudflats, saltmarshes and lagoons. The Abbotsbury Swannery has been pampering mute swans since 1393!

Gulls are seen on a daily basis, ranging from herring gulls to the uncommon common gulls. It takes more patience to spot various divers, skuas and auks, while trips to specific locations at the right time will reveal puffins, gannets, petrels and shearwaters. Mudflats and saltmarshes are good places to spot oystercatchers, avocets, plovers, sandpipers, knots, godwits, redshanks and greenshanks. Terns favour high storm beaches, where their eggs are camouflaged among pebbles. Choughs, a rare red-legged crow, are only rarely spotted along sea cliffs, while other species of crows prefer to stay further inland. There are reedy marshes, woodlands, fields and rivers near the coast, so other birds spotted include warblers, wagtails, flycatchers, owls, woodpeckers, treecreepers, nuthatches, thrushes, pipits, wrens, larks, tits, starlings, sparrows, blackbirds, cuckoos, herons, egrets and maybe a quick blue flash of a kingfisher. Birds of prey include buzzards, hawks, kestrels, falcons and harriers.

Culture

There’s a certain historic rivalry between inhabitants of Devon and Cornwall, but it can be difficult for visiting tourists to understand the nuances. Taking pasties as an example, the Cornish crimp the edge of the pastry, while in Devon they crimp it along the top. With cream teas in Devon, the cream goes on the scone, then the jam goes on top; in Cornwall the jam goes on the scone, then the cream goes on top. Both camps are prone to get a bit weary when over-run by hordes of visiting tourists. In Devon, tourists may be disparagingly referred to as ‘grockles’, while in Cornwall they may be referred to as ‘emmets’. The counties of Somerset and Dorset also have their own strong identities and county pride.

Of all the counties in the south-west, Cornwall boasts a strong identity tending almost towards nationalism. The Cornish language, which died out centuries ago, is enjoying a revival and is spoken to some extent by a few thousand inhabitants. It has some similarity with Breton, closely followed by Welsh, as they are all Brythonic tongues. Cornwall has flown the flag of St Piran for about two centuries, and its design, a white cross on a black background, has been in use for much longer. Neighbouring Devon, Somerset and Dorset all scrambled to design their own specific county flags only in the past few years.

Whatever else happens in the south-west, Cornwall tends to go a step further. There’s a greater awareness of cultural identity, reflected in everything from language, literature, song, dance and traditions, to a revival in Celtic Christianity and old Pagan practices. A glance at a map reveals a bewildering number of ‘saints’ in place names. There are Cornish sports and games, along with plenty of Cornish societies and groups. In fact, there’s a Cornish diaspora, dating from a time when miners were sent to mining operations around the world, where they retained their identity and close family ties even to this day.

Coastal walking through history

Man has been active along Britain’s coasts since Neolithic times. The earliest settlers were hunter-gatherers who lived in the valleys and on the coastal margins, at a time when most of the inland areas were heavily forested wilderness. These people may have initiated some vague paths along the coast, and maybe you will walk partly in their footsteps. Bronze Age fortifications and Iron Age promontory forts along the South West coast signify a level of social unrest and strife as waves of settlers came from Europe. In more peaceful interludes, people surely trod along the coastline.

Boats hauled out of the sea at the little fishing cove of Penberth (Stage 20)

Fishing and seafaring have always been important activities. There are dozens of natural sheltered harbours with deep-water channels. Villages and towns grew up around these, and fortifications were built to afford them protection from raiders. A lookout for unfamiliar vessels would have been maintained from the clifftops. Fishermen also manned cliff-top lookouts to spot shoals of pilchards, mackerel or herrings, and would raise a ‘hue’ to let their comrades know where to make a good catch.

Fishermen and sailors were ideally positioned for wheeler-dealing with foreign vessels, and when heavy duties were slapped onto imported goods early in the 18th century, they used their intimate knowledge of the coastline to land all manner of goods at remote spots. The government responded by administering harsh penalties and punishments, but the smugglers simply became more devious. The government retaliated by establishing the Coastguard Service in 1822.

Coastguards were stationed at intervals along the coast to patrol the cliffs and coves, keep an eye on any suspicious activities, and clamp down on the smuggling trade. They tramped back and forth along their coastal beats, treading out clear paths with unrivalled views of the rugged coast. The coastal path largely came into being from that time.

As the coastguards were suppressing an illegal activity that local people felt was important to their survival, they were most unwelcome. It was almost impossible to procure accommodation for them, so they were obliged to live in specially constructed coastguard cottages, often well away from towns and villages. Even after renovation into holiday homes, some coastguard cottages still resemble military barracks. Over the years, coastguards became less involved in watching smugglers, and switched to scanning the seas to ensure the safety of passing ships. Often they were stationed in lonely lookouts on prominent headlands, with binoculars, telescopes and notepads. The modern Coastguard Service is now centrally administered.

A cliff-edge cottage is passed on the way from Thorncombe Beacon to Eype’s Mouth (Stage 40)

Many old coastguard lookouts have been reopened by the National Coastwatch Institution, www.nci.org.uk, a charity made up of volunteers who take on the role of the former coastguards. They keep an eye on shipping, and also on Coast Path walkers, and are now recognised as an important part of the emergency response network along the coast.

Today, use of the Coast Path is rather different. Almost everyone who walks on the path does so for exercise and enjoyment. Ramblers may walk from one town or village to the next, while long-distance walkers simply keep going day after day while the infinite variety of the route unfolds before them: beaches and bays; cliffs and coves; sea stacks and sand dunes; fishing villages and holiday resorts. With all its ups and downs and ins and outs, the route is often like a monstrous rollercoaster and leads walkers through history and heritage, scenic splendour and the wonders of the natural world. It has been estimated that anyone completing the whole trail will climb four times the height of Everest!

Many towns and villages along the South West Coast Path have fine little museums or heritage centres, with fishing and smuggling being oft-repeated themes. Visit them to obtain a clearer picture of local history.

A protected coastline

The South West coast is largely cherished and protected, but has been spoiled in a few places by industry and inappropriate development. The Exmoor National Park covers the early stages, and much of the coast of North Devon, Cornwall, South Devon, East Devon and Dorset is designated as Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The last long stretch of coast was designated as England’s first Natural World Heritage Site: the ‘Jurassic Coast’. Many stretches are Heritage Coasts, while smaller areas may be protected as National Nature Reserves, Local Nature Reserves or Sites of Special Scientific Interest. The National Trust own and manage around 500km (310 miles) of the coast, some of it acquired during their long-running ‘Operation Neptune’ campaign.

Looking after the Coast Path

The South West Coast Path is looked after by a partnership of organisations. Maintenance is undertaken by the County Councils and the National Trust and coordinated by the South West Coast Path National Trail Team, with support from the South West Coast Path Association (a charity) and funding from Natural England. They work together to ensure that any storm damage, broken signposts, stiles, footbridges and much more, are all repaired and cared for.

Following reductions in government funding in recent years, the Association has taken on a vital fundraising role to help support these important projects, and also works hard to encourage everyone to use, enjoy and ultimately love the Coast Path.

The South West Coast Path Association was originally founded in 1973 to act as the voice of the trail, generating support and awareness of the route and lobbying for the path to be the complete 1014km (630-mile) trail it is today. As it costs at least £1000 for every mile of this glorious trail to be kept open and clearly signed, the Association asks for your support to help look after and love the path. Whether you use it to walk the dog, have family picnics, to escape on holiday for some fresh sea air or enjoy it as a serious walker: if you love it, please help to protect it.

The easiest way to do this is to become a member of the Association, with annual membership being available for less than the price of a pasty or a pint per month. The Association also has a wide range of South West Coast Path gifts and essential walking items. By supporting them you are supporting the path. Please visit www.southwestcoastpath.org.uk, tel 01752 896237, hello@southwestcoastpath.org.uk, for further information.

Walkers who spot part of the route that needs repairing are encouraged to report it, either via the website (look for ‘report a problem’) or by emailing the details to hello@southwestcoastpath.org.uk. To help the rangers locate it, please ensure that you note the location (ideally a grid reference) and it is also really helpful if you can include a photo.

The severe winters of 2012, 2013 and 2014 hit the coast of the South West hard and resulted not only in the main railway line into Devon and Cornwall being temporarily severed, but it also caused many cliff falls, requiring a huge amount of work to reinstate the Coast Path. Thanks to funding secured by the Association from donations and the Coastal Communities Fund, the majority of this damage has now been repaired. The website carries the latest information on any remaining diversions, so it’s well worth checking in case things have changed since this edition was published.