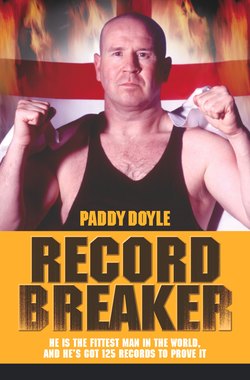

Читать книгу Record Breaker - He is the Fittest Man in the World, and He's Got 125 Records to Prove It - Paddy Doyle - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

HEADBANGER

ОглавлениеI HAD AN IDEA I’d go back into the army later on. But, just then, I wanted to live life. I was eighteen when I learnt to drive, but each driving instructor I had passed me on to another one. They didn’t like the way I kept putting my foot down on the accelerator. During one lesson we drove over some hills, a great walking and driving spot, and I decided to put my foot down. I was yelling like a cowboy, ‘Yahoo!’, as I speeded along.

All I could hear was the voice of the instructor shouting, ‘Slow down! Slow down!’

And I shouted back, ‘Ah, shuddup! What’s the matter with you? I gotta have some fun!’

When I turned up for my lesson the following week, I found the instructor had sent his brother along instead. He took me out for my lesson and, again, I was a bit courageous and put my foot down. At the end of the lesson the brother told me I’d have another instructor the following week. It turned out to be a different driving school altogether. That’s how far they’d passed me on. Washed their hands of me.

I was given a few more lessons, this time by a female instructor, and I drove fairly carefully. Then I moved house, to Quinton, another district in Birmingham, and started with another school of motoring. After numerous lessons with a new instructor, my driving improved. I applied for a test and failed it, and put in for another one. As usual, we went for the hourly drive around the area before the test. I looked across at the guy and saw he was drinking cans of super-strength lager. He was an alcoholic and had a load of cans under his seat. He wanted to go for a drink with me after the test. I just wanted him to drop me off, as fast as possible. But he must have brought me luck because I passed my driving test that day.

When I came back from the Junior Paras, I moved from my father’s to my mother’s house. I was sixteen and a half at the time, and I soon got a local job, working in Tesco, pushing trolleys, stacking shelves and helping out with security. The area where the supermarket was situated, near Ladywood in Edgbaston, had a high rate of crime and they needed help looking out for shoplifters. A lot of alcoholics and drug addicts used to come in and shoplift. You never knew what these people were carrying. They’d use bottles if they were approached, to make good their escape. I wasn’t hired to be part of security personnel but I was happy to help when assistance was needed.

At the time it was the commissionaires who were in charge of security. These were fairly elderly gentlemen, ex-forces. I respected those guys. I said to them, ‘If you get any problems, I’ll help you out.’ And sometimes they did need assistance. If I saw them trying to restrain a violent shoplifter, I’d run to their aid.

One incident happened, not in the shop itself, but in the car park next to the store. A guy there was caught looking at cars and the police were called. I could see the police in a scuffle with this young lad. A police officer was on top of him. I ran out to see what was going on. But I was in two minds whether to help or not.

It was a moment of divided loyalties. I was a lad who’d come from nothing. I wasn’t sure whether I was with the policeman or the guy who’d got caught. I had to stop in my tracks. I couldn’t help out. The police officer looked at me. Our eyes met. He understood. He said to me, ‘Don’t even think about it. Don’t you come near me.’ That was the turning point. I didn’t help out. I did nothing at all. Just stood there. I was at some kind of crossroads, staring down two paths. If I’d helped the potential thief, then I don’t know which of those paths I’d have taken.

After that, I started to get my act together. Now, if I saw a police officer getting beaten up, I’d help him straight away. But at that age you don’t know the direction you’re travelling in. You’re still finding your feet. And I’d had run-ins with the law myself. They weren’t my best friends at the time.

But that was it: a subtle change of direction. It went undetected by me at the time. I carried on at Tesco for another twelve months but I began falling out with the management, having disagreements with them. I was seen as a bit of a headbanger, a rebel. That was how I was projecting myself, and it was causing me problems. Not that I got the sack from the job. What happened was I was called into the office one day. I’d been having disagreements with other members of staff and they were getting weary of me. I’d be picking fights with the men downstairs in the warehouse. I was a complete tearaway. If I disagreed with someone, I’d say, ‘Right, I’ll fight you.’

Some fellow would make a remark, and I’d make one back and it would escalate from there. I wouldn’t react in that way now; I’m too mature. But then, I’d say, ‘I’ll fight you now.’ I had a lot of anger and aggression inside me, always about to explode. Maybe it was to do with one or two bad patches in my childhood which had left a certain amount of bitterness. I hadn’t got on with my father’s woman friend. There’d been ups and downs at home.

Tesco realised they had a problem with me. The final straw was when I offered to fight one of the butchers in the store. He already had a large butcher’s knife in his hand, but I said, ‘I’ll still fight you with that.’ I didn’t care what the guy had in his hand. He wouldn’t fight me. He probably went straight to the manager. Someone did.

The manager called me into his office and said, ‘Paddy, we’d like you to leave. We’ll give you a good reference and two months’ money.’ And they did. Tesco stood by me, but they didn’t want any more of my kind of trouble. I got another job, part-time, in another supermarket closer to home, just to bring the money in. I was there seven or eight months and I started working as a doorman in the evenings.

I was introduced to the evening work by a friend of mine. He was already ‘on the doors’. I started off by working with him in a couple of pub discos, then I graduated from there. At first I was freelance, looking after DJs. The club manager would ask us to come in. Pub discos have a lot more trouble than nightclubs. Dress is more casual; it’s a local venue and the people wear jeans. Families drink in there, and there’s sometimes confrontations between families. In that situation you’re not just a doorman, you’re a social worker trying to calm down the warring factions. It was a good training ground for me.

I started out doing the doors for the Talbot in Hagley Road, Birmingham, and the Duke of York at Harborne. After a while I gave up the supermarket work and only worked at night. Then I got a job at Snobs nightclub, near Broad Street, in the centre of Birmingham. There were a lot of youths there between the ages of about eighteen and twenty-four. It wasn’t a nightclub with a mature clientele, so there was trouble regularly.

One night we refused to let a football team into the club. They started smashing the front windows and kicking in the front door while we stood there, trying to contain the situation. Another time things got out of hand downstairs. A group of lads were getting boisterous. I went down there, thinking I had the back-up of the other four or five doormen. But they’d disappeared; all happened to go to the toilet at the same time. I was the shortest guy there and I had to go in on my own. Well, I used my head to sort out the fracas, and it paid off. But I didn’t work for that club again. Those doormen had lost their bottle. They’d let me down.

Around that time I’d been going for lads’ nights out with the guys from Tesco and getting into scrapes and fights, with doormen and other gangs of youths around the city centre. We’d go to clubs and pubs and, after a few drinks, we’d be creating trouble.

On one occasion we went for a night out, starting at the Crooked House in Dudley. The Crooked House is an old pub on the slant, like the Leaning Tower of Pisa. You go inside and the bars are on the slant. We had a drink in there, then we went back into the centre of Dudley and found a pub disco. There were about four of us. Some guys in the disco were taking the mickey out of us, so I said to them, ‘Well, come outside and look at my car.’ They fell for it. They followed me and, as they stood looking at my car, I struck out. There were four of them and I hit two. They’d been getting aggressive inside the disco, but I didn’t want to start a confrontation in there. I wanted to ask them what it was all about outside. My friends came along with me, but I did the fighting. They stood by, shocked. Like the mickey-takers, they’d believed I’d actually wanted to sell my car. We left them there and drove off.

Looking back, I do regret some of the incidents I instigated. I was far from perfect, I’ll be honest. I was a young man, full of aggression. I started confrontations unnecessarily. I looked for trouble then. I’m a different person now. From about seventeen to twenty-one I was known as a troublemaker, especially by doormen of pubs and clubs. I was banned from a lot of the clubs in Birmingham for a very long time. I was a problem for the club owners. I had a lot of rage in me. I’d drink and cause fights. Once or twice I even knocked out doormen.

When I was about nineteen, I was in Horts Wine Bar in Edgbaston. I was with a friend and we were talking to a girl, not realising that the girl was going out with the doorman. He was a giant of a man: about six foot three. We were pleasant to the girl and we didn’t think anything more about it. We were going through the door when the man threatened me for talking to his girlfriend. I apologised and said I didn’t realise she was with him. But he got aggressive, so I hit him. I only weighed about nine and a half or ten stone but I knocked him out.

I didn’t plan it. It was only when he went over the boundary of normal threatening noises that I reckoned I’d have to do something. I looked at our difference in height and struck him on the jaw, punching upwards. He was on his back. He dropped like a sack of spuds.

But I reckoned I was in the right. I’d apologised to him. I’d told him I wasn’t aware the girl was his girlfriend. But the guy came forward and wanted to carry on the argument in front of a group of people, including his girlfriend, so I had to think quickly. But I didn’t realise a friend of the gaffer of Horts was talking to the doorman at the time, trying to calm down the situation. I told the gaffer the other guy had started it, but we still had to leave. We walked off to the car and disappeared.

Twelve months later we were in the same wine bar. I’d been to the gym, then gone on to the wine bar with a friend of mine. We shared a bottle of wine and I’d had nothing to eat, so I got drunk. I went to the toilet and there were two giant blokes in there. I kept thinking I was going to get mugged and I’d better do something. So I hit the two of them. I was wild in those days. I just hit them against the wall. I walked out and rejoined my friend. Next birthday he got me a T-shirt which had on it ‘Paddy Doyle Giant Killer’.

The doorman at Horts knew us and he couldn’t stop laughing. He made a joke out of the incident. He kept saying, ‘It’s good here, isn’t it?’ But I had to leave. I went home with my friend and, when we got to his house, he left me in the car because I was so drunk. He thought I’d sleep it off. When I came to, I didn’t know where I was. I kicked all his windows in, trying to get out. I completely wrecked the car. Kicked his door through. I was crazy; I didn’t know what I was doing. I only knew I wanted to get out of the vehicle.

During those three or four years I was in a bubble of my own: a total headbanging rage. I used to go out with my mates, not to find a girl but to have a confrontation. If I woke up on a Sunday morning and I hadn’t had a fight the night before, I reckoned it had been a bad night. I didn’t need drink to fire me up. I’ve never needed drink like a drug. But drink was acid to me.

And I was hanging around with blokes who were older than me, in their late twenties and early thirties. They were a load of crooks and villains and they could see the potential in me. They took me on board and led me in their direction. And I admit I was happy to go that way for a period of time.

I was never involved with drugs. I was never a thief. But I was involved in violence. Because I was a headbanger, people would see me as the right person to sort out problems. I’d get money for it. Businessmen would ring me up and say, ‘Sort this out for me, Paddy. There’s this amount of money in it for you.’ So I’d go and scare the people.

As I got older I was veering towards being part of the heavy mob. I had a reputation, even at nineteen and twenty. I was doing the doors at clubs and discos, but other doormen were wary of me. They were established hard men and I was still a youth. They’d take one look at me and they knew I was a problem. Once one doorman knows about you, they all know. Even when I went into the regular army, the Paras, later on, I was coming home on leave and getting a reputation.

I also began to get seriously interested in amateur boxing around that time. The sport helped me find my feet. It channelled my aggression. I wanted to develop my strength, so I decided to take up weight training. There were a number of gyms in Birmingham, but word gets around about which are the best and I went to a reputable club called the Harborne Weight Training Centre, which was owned and run by a guy called Ralph Farqharson.

I was doing gym work, amateur boxing and weight training, all at the same time, and the last gave me added strength. Ralph Farqharson became my trainer. He’d been the World Masters Power Lifting Champion and had a Guinness Book of World Records title for beer-barrel lifting. Unfortunately the record was broken after a couple of months by a Swedish strong man. But Ralph was to become a good friend.

Ralph set about showing me the techniques for lifting and I was glad to learn from a champion. He has two gyms: the Harborne Weight Training Centre, where I trained, and another weightlifting gym in Tyseley, which is also in Birmingham. I still see him and his wife, Sharon. Lovely couple. Genuine people too. Down-to-earth, working-class people who’ve worked their way up.

Ralph began coaching me on the weights, which gave greater power to my fighting ability. He taught me the technique for lifting: bend the knees, flat back and head up. Never lift anything up with your legs straight. And only lift the weights you’re comfortable lifting. I began experimenting with my body, pushing it to its limits. I enjoy weightlifting, but it became obvious that I was doing too much of it at the time. I had muscle, so I had strength, but not flexibility. I was training as much as a weightlifter does, not as a boxer or an athlete. That was ignorance on my part, wanting to go the extra mile. The result was I increased my body mass and that made me less agile in the ring.

I’d always loved boxing, even just sparring in the gym. But I loved getting into the ring and fighting properly. There’s nothing like the real thing. At first I worked in Tesco during the day and did my weight training and boxing in the evening. I’d get the train straight after work to the boxing club or to the gym. Practically every night I was somewhere, doing sport. And Friday night I was out with the lads.

I had kept up the boxing for about four years. I was seventeen and working on the doors by then. Being a doorman, you could see where I was going: in the direction of the heavies, the guys who were the gangsters. Doormen and bouncers are hard men, good to have on your side. There I was, a seventeen-year-old, and trying to stop grown men coming in the pub, drunk. It was hard work.

I remember one pub I was working in, where a guy took a knife out. I didn’t have any fear. I stepped in between him and the guy he was threatening. I took the knife away from him and threw him out. Fear just wasn’t there when I was young. I’d rather have died than lost a confrontation, as demonstrated a decade or so later when I was stabbed in the leg.

I’d never got beaten up in the playground at school, thank God, but when I was about twenty I got beaten in a gang fight. We were outnumbered. There were three of us at a club in the centre of Birmingham. We were completely set up by a large gang of lads, about a dozen of them. At first we didn’t know what was going on. Two of my friends had chairs land on them from over a table and I got jumped on from behind. I was punched and kicked around the floor. Unfortunately I’d had a few beers and I didn’t know what was going on. I lost my two bottom teeth. I felt them go, felt the crunch. I was attacked from behind and, as I was being pulled back, someone must have thrown a punch or an object at me. I was dragged on to the floor, but I kept fighting.

After that, all I remember was getting up off the floor, eyes turning black and blood pouring from my mouth. I went over to collect the other two lads, who’d been knocked cold with the chairs. One of them was still out, snoring. He wasn’t cut but he had a hell of a lump. I pushed the other guys off him, just as another chair was about to rain down on his head. It could have been the final blow to a delicate part of his skull. I got him on his feet and dragged him out of the door. I wasn’t going anywhere without my mate. It was loyalty. We may have been outnumbered, we may have been beaten, but you don’t leave without taking your casualties with you.

I’d always intended to go back into the Paras. I didn’t see much future for me in door work. I was coming up to twenty-one when I applied to join the Parachute Regiment. By the time I’d won my first amateur boxing competition, I’d been through the army’s selection procedure and their interviews and was ready to join up. I think the selection process was a lot harder than it is today. The whole process takes three or four months. There are the usual police checks and they take up references. It costs thousands of pounds to train a soldier, so the army has to protect its investment as best it can. They have to be sure you’re the right man for the job, as far as possible.

I joined the Paras because I knew it would be tough and demanding. I wanted that challenge. It appealed to my aggressive nature, my determined nature. In March 1984 I was back at Browning Barracks, where for the first six months I was just a recruit. One hundred of us joined at the same time. Six months later seventy of the lads had left or failed the recruitment. Only thirty of us got through.

I could see the numbers in our block dwindling day by day. Men were missing their families, missing their girls. What I’d gone through at sixteen when I’d joined the Junior Paras, they were going through at the age of twenty-one plus. What I’d thought I was missing out on four years earlier, they thought they were missing then. They must have been leading a boring life up to then. Me, I’d lived a bit. I’d got the mad nights with my mates out of my system. Or so I thought.