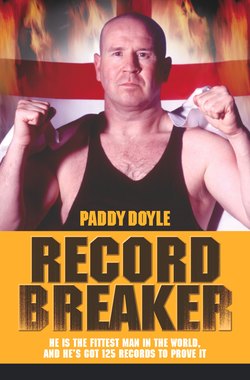

Читать книгу Record Breaker - He is the Fittest Man in the World, and He's Got 125 Records to Prove It - Paddy Doyle - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ATTACK!

ОглавлениеA REGULAR EVENING. I’m driving down an ordinary street in the suburbs of Birmingham, coming back from a training session at my gym. I’ve been teaching the martial arts to a group of students and I’m cruising along, my mind on a self-protection course I’m giving the following week at the local adult education centre. Little do I know, I’m about to put my years of training and experience into practice.

Ahead, I can just make out a white car. There are four black guys standing there. Big guys. Tall and big. They flash me down. I decide they must know me from somewhere. Probably one of the local boxing or martial-arts clubs I train at. I pull over. Just as I stop, one of the guys comes running over to me. I can see he’s well over six foot. And I can see I don’t know him from Adam. By this time the guy is at my window, and so are the others. One of them opens my car door and grabs my arm. ‘Get out of the car, quick!’ he barks at me.

Well, I’m my own man, always have been, and I tell him where to go. But he’s got hold of me and he’s pulling my arm. Now, all my natural instincts rise up, and I start punching and kicking out. At the same time I’m out of the car as fast as I can be, so I can have a proper go at this guy. Two more men come at me, then another. Something flashes, glints. But I’m busy; my mind is elsewhere, the adrenalin is flowing. At first I don’t feel anything. You don’t when you’ve got eight arms coming at you.

I’m still battling with them when I see one of the guys is wielding a knife. Another has a Stanley knife and he’s shoved it into the calf of my leg. The first guy jumps into my car. I can hear him shouting, ‘I can’t start it! I can’t start it!’ It must be the cut-out switch. No time to lose. I run over and kick the car door, trapping the man’s head between the roof and the side door. I’m angry I’ve dented my door but it’s better than seeing the car disappear down the road.

I turn and run back to the other guys, shouting, ‘Come on then!’ But I can see they’re starting to flap. They’re not ready for this kind of confrontation: a driver ready to go for it. Someone says, ‘Let’s get the hell out of it, quick!’ I’m still putting up a fight as the four blokes run away. Four guys don’t bother me. I’m doing what I have to do. I’m not going anywhere.

Funny thing was, there were witnesses to all of this. Grown men, standing there, looking out of the windows of their houses. When the fight had finished, these people went back to their armchairs and sat back down to watch their TVs. Not that I needed any help with the situation. But it would have been OK by me if someone had phoned the police. No one did. Turns out later, in one of the police statements, that these respectable householders thought I was messing about with those guys, having a laugh.

I reckon it was a cop-out. People don’t want to get involved, don’t want to know. They want to protect themselves. Don’t tell me you can’t see from your window who’s messing about and who isn’t. I didn’t need their help. All I’d wanted them to do was ring the police so they could catch the guys, instead of me just chasing after them. Then I could have stood up in court and pointed out who’d stabbed me.

The police officer looked at me and shook his head, as if to say, ‘What can you do? People just don’t want to help out these days.’ Not long after that I managed to acquire one or two addresses, and I made it all good for them. It was about four or five o’clock in the morning when I knocked on their doors. I might have scared them a little, got them out of bed, something like that. Well, it’s a mental game.

And they might have walked out the next day and found various objects around their front doors. Maybe they had to move house. I might have scared them out of their own homes. They might have thought I’d have done their heads in. Maybe they’ll help someone out next time.

But, the night of the attack, I went to bed and slept like a log. All those years of military training in the Paras, the security work, the skills I’d acquired in boxing and the martial arts, the fitness and endurance records I’d set and the courses in self-protection I’d given to others: they’d all paid off that night. I’d done what I had to do. I saw those attackers off. They ran like cowards, and they didn’t get my car. And I wouldn’t hesitate to do it again.

Next time I’ll probably hospitalise the aggressors. They may never breathe again. At the time there was an element of surprise when they attacked me, but it’s been rehearsed now. If anybody tries to take my car off me again, they’ll be six foot under. A local reporter rang me up not long after the incident. He’d seen the articles in the Sun and the Daily Star about how I’d defended myself. He asked me, ‘What would you do if you saw those guys again?’ I gave him a quick résumé, mentioning axes and saws, limbs and acid, plus certain burying techniques. He didn’t print my reply.

Another time, in 2001, I was on my way home from a boxing martial arts class, where I had been teaching, and my next-door neighbours, who had been creating friction between them and other neighbours ever since they had moved in about eight months beforehand, were out on the street as I parked my car up, and at it again.

On this occasion, I could see the father and son (who lived next door to me) ganging up on a resident (who lived opposite me), by threatening him with a car crook lock. The son was shouting, ‘Don’t mess with me, I am a blue belt in kickboxing!’

I walked over to calm the situation and then the pair of them started to get aggressive with me. Responding to their threats I warned them that I would rip their heads off if they didn’t cut it out. I told the son to follow me and took him round the back of my house. ‘It’s just you and me,’ I said, ‘so why not fight me instead, lets sort it out now.’ To my surprise he started crying and crumbled in front of me. I told him to hop it and stop acting the hard man.

The next day, one of the neighbours bought me a bottle of red wine and thanked me for stepping in to sort the problem out. Recently things had been getting nasty, because this family were also giving verbal abuse to other residents who were trying to help this neighbour being bullied.

I thought they would start behaving themselves after the confrontation, but to my surprise the father was being arrogant and cocky with me, making loud noises at night and generally trying his luck. The problem needed sorting. Two weeks after the initial confrontation I decided to do something.

He always got his van out of the garage about 8 o’clock most mornings. That morning, I decided to wait for him. As he came out, I approached him and told him that I wanted to have a straightener with him. He went white as a sheet and started shaking. He told me that if I touched him then he would go to the police and the papers. It goes to show that when you get these so-called hard, arrogant bullies on their own, they just crumble. They only pick on people who can’t defend themselves. I was glad I was there to help out.

All the confidence and fitness that goes with being a champion had seen me through those nights. Over the previous fourteen years I’d broken some of the world’s toughest fighting and endurance records. I’d featured in The Guinness Book of World Records every year for twelve years, run London Marathons with forty-four-pound backpacks, broken stamina records on television and overseas; I’d done it all. But there was one world record left that I wanted to beat. Just one more before I felt I could retire. It would be my one hundred and fourteenth record challenge. A teneventer with all the press and television there. The decision to retire had been a tough one but, at the age of thirty-seven, I wanted to finish my record-breaking career without serious injury, in competition or training. On 25 November 2001, at the Fox Hollies Leisure Centre in Birmingham, I had to go out at the top.

I was born Patrick Daniel Doyle on 1 March 1964 at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham. My parents, Patrick and Bridget Doyle, were living in Erdington at the time, an area north of Birmingham city centre, near Spaghetti Junction.

My parents had come across to England, with other members of their family, from Ireland. My mother was a Derwin and came from Rathmines in the Dublin mountains. My father came from a farming background in County Wexford. My father’s mother had died not long after he was born, and a couple of years after that his father died. So he never really got to know his parents. Just one of those things, a sad circumstance.

He was raised on a farm with his cousins by his uncles and aunts. When he was a young man he moved to Dublin to find work, and that’s where he met my mother. I’m not sure how they met. Probably at a dance. They loved dancing.

My mother had the family background my dad had lacked: a real father and mother, three brothers and three sisters. People had big families back then. But, quite often, some of the children died young. My mother’s background was more of a city upbringing. Rathmines is now a posh part of Dublin. Very nice, a very conservative area. Her mother was a seamstress, I think, and my grandfather was into a bit of everything: taxi-driving, building work, stuff like that.

My maternal grandfather was a big man, and something of an athlete as well. He joined the Irish Defence Force, the Irish army, for a dare in 1914 and was billeted in Wales. The first night he was there he was looking for somewhere to sleep and he stuck his head in a tent and got a boot on his head for his trouble. Most people would have left it at that, but he followed the soldiers in that tent, as best he could, and they were all sent to Italy to fight. One night he was sitting round with some other soldiers, swapping tales, when a bloke said, ‘I’ll never forget the night a fellow put his face in our tent and I gave him the boot, right on the head.’

My grandfather sprang up. ‘Oh-ho!’ he said. ‘I’m your man!’ The other guy jumped up and went outside the tent with him. They had a pretty good fight, and there was an officer looking on as they fought. Like my grandfather, the other fellow was a good scrapper, but the fight went my grandfather’s way.

Not long after that the army boxing tournaments came up and my grandfather saw his name was on the list of bouts. He deleted it. He’d never boxed in a ring in his life. But the officer who’d seen him fight that night came up to him and said, ‘Did you cross your name out?’

My grandfather said, ‘I did.’

The officer said, ‘I put your name on the list. You can do it, you know. You can win. And I’ll be your second.’ And that’s how my grandfather got into the ring. I suppose his fighting methods would have been different from other people’s. They wouldn’t have been by the book, but they wouldn’t have been foul either. He became the army’s Amateur Heavyweight Champion. He only ever went two rounds, even though a fight goes to three. He’d won by then.

He loved horses, as well, and fought in cavalry charges in Russia. He said the Russians were lovely people. But he was out there to do a job. My Uncle John used to ask him if he’d ever killed anyone. My grandfather would never say.

Grandfather was a bit of a character, by all accounts, and I think I’ve inherited his personality. He was a gentleman but nobody stood on his toes. He was over six foot one, which was tall at the time, and stocky and strong. My first cousins take after him: very tall, six-footers. My side of the family drew the short straw; we’re the shorter ones. Grandfather Derwin won a number of cups and medals and my uncles in Ireland have kept them. As well as being a good amateur boxer, he was a sprinter and a competitive cross-country runner at a high level. But there was no money in sport in those days. Even today, I don’t believe there’s much money in cross-country running.

But sport isn’t about money. It’s the winning that counts. It’s the will to win, regardless of the level you’re at. Until my retirement in November 2001, I competed in a number of minority sports, from circuit training to strength, speed and stamina, from boxing to the martial arts. I didn’t focus on just one particular strength or aspect of my body. I was an all-rounder. I excelled in several disciplines. My grandfather would challenge people to run against him and I was just the same; I’d check out the record books, looking for a challenge. If I thought I could beat a record, I’d train for it and go for it. I got my competitive spirit from my grandfather; he had that sporting will. He was a hard character, a tough one. I think that’s how you had to be in those days to get on. And I’ve inherited that from him too: the capacity to focus, to be disciplined. He had a mindset and the level of commitment that I’ve got, so I reckon it’s in the genes.

Grandfather Derwin ran his own taxi business in Dublin. He made golf clubs, patented a car battery carrier and he supported seven children. He was a goer and trier. When I’d broken a record for, say, fitness and endurance, my uncles and aunts would say, ‘You’ve got that fighting spirit from your grandad.’ They could see his approach to a sporting challenge in my attitude. They saw it in my body language, the way I projected myself and my physical mannerisms. A while back I saw a photograph of the man himself: broken nose and cauliflower ears, probably from the boxing. Cauliflower ears are the result of blood clots that form when your ears are pounded. You don’t see many these days because people wear head guards. My nose was broken in a fight, but it was a clean break and it was reset.

I saw some of Grandad’s trophies about five or six years ago. His medals are in Dublin with one of his sons. I only ever saw my grandfather once, that I remember. He had a full face like me, a thick neck, as I have, and he was muscular, as I am. He looked at me, all those feet below him, and I looked up at him. I was probably about three or four, and you don’t hold conversations with people when you’re that age. He must have been in his seventies or even his eighties then, because my mother had me late in life. So I never really knew him.

Mum was forty-four when I arrived. I wasn’t planned. My brother and sister are around ten years older than me. I can see myself in my mother, as well as in my grandad, both physically and mentally. Like my grandad and me, my mother is a stubborn character. And she was a competitor too. She was a ballroom dancing champion in Ireland in her younger days. She won a cup. I think it was David Nixon who presented her with the trophy. My dad used to dance too. And that’s probably where they met, on the dance floor.

My father died in 1985, when I was in the army. My mother’s eighty now. She still talks occasionally about her dancing days. When my brother got married recently, she was watching the dancing and reminiscing about her days as a ballroom champion. But she’s in a wheelchair now and, I think, because she can’t get up and dance and socialise now, it’s a bit of a setback for her. She’s got the family energy and competitive spirit, and it came out in a feminine way with her dancing. Ballroom dancing competitions are very demanding physically, and you have to commit yourself to train for events. And she did just that. To this day she’s mentally active and strong-minded. Nothing’s changed with her; she doesn’t miss a trick. She’s still Mum. Nobody can put one over her, but it could be the other way round. She’s the old school and she’s good at getting attention. She likes it, just as she did when she was dancing. She likes people around her. She’s a social person.

My dad was a sociable person too. He loved people and got on with everybody. Never had any enemies. My oldest brother, Declan, was born in Ireland and not long after that, in the early fifties, the family came to England to look for work. They went to Aston, which is now the rough part of Birmingham. My mum used to tell me that when they first came over, there were notices in the boarding houses saying, ‘No dogs or Irish allowed’. It was like that then. But the country needed extra labour after the Second World War and my father got work with some engineering companies, and eventually we moved to Erdington.

Then my sister Bridget was born and my brother Eddie came along after that. I was the afterthought in 1964. But Eddie was to die young. He drew the short straw and died of cancer when he was thirty-five, leaving five kids. I think his illness might have been related to smoking. There was a gap of about ten years between Eddie and me, so I was almost like an only child. And I got very wild.

A factor in all of this wildness might have been my mum and dad splitting up when I was four years old. That’s when things started happening in my life. I went to live with my father. My mum had met someone else and it was decided I should go with my father, probably because I was such a handful. My brothers and sister were that much older, so I was the only one who went to live with Dad. The others were growing up and leaving home around that time, making their own lives. Declan joined the army at sixteen.

Mum moved to another part of Erdington, about three or four miles away. I used to see her every Sunday for four hours, and had a great time. I got a good Sunday lunch as well. Dad found a job with some builders, working on the construction of Spaghetti Junction, the motorway link. He did that for a couple of years and it was during this time that I really started getting wild. But I think I had a rebellious temperament, even before then. I was always a livewire, from the moment I was born. Always was a problem.

One incident I don’t remember, but I’m told happened, was when I was about two or three years old. I picked up my mother’s purse. My father had just given her all his wages and she’d put the money in it. I threw the purse on the fire. For days after that we were broke and everyone had to scrape around for food. A year or two after that, I’m told, I couldn’t go out to play for some reason. So I climbed the garden wall to get out, fell and broke my arm. I was whipped off to the hospital to get it reset, but that didn’t stop me getting into scrapes. I was bolder than other kids of my age and always getting into trouble.

Already I was hanging around bigger boys, about seven or eight years older than me. If they got into some mischief, I’d be there with them. Often the episodes got out of hand and we’d end up damaging property. Things could get violent, even at that age. I ended up behaving like a crazy little kid. Dad used to put me to bed before he went off to work, but I used to get up and slip out of the front door. Some nights my dad would go out on his night shift and as soon as he’d gone I’d sneak out of the house. I’d be out playing, at the age of five, at ten o’clock at night and he didn’t know anything about it.

But one night my dad caught me. He was on his way to work and he caught me playing on a motorway with some other lads. The motorway was still being built then and it was a great place to play football.

Sometimes we kids would climb eighty-foot ladders, those big old wooden ones, to get on to the motorway, just for a laugh. I wouldn’t do it now. And, during the day, we’d run up and down the motorway link and have the workmen running after us, trying to chase us off. And we’d slide down the ladders again to get away fast. Well, you’ve got no fear at that age. It was to be the same as I grew older.