Читать книгу Temperance Creek - Pamela Royes - Страница 23

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHittin’ the Trail

“I’m hittin’ the trail tonight,

I’m hittin’ the trail tonight,

The horse is pullin’ at the bridle reins,

I’m hittin’ the trail tonight.”

—BRUCE KISKADDON

Jim, the man selling the horse, told us where to find the herd and suggested we bring a little grain as enticement. Pretty big pasture, he’d said. Couldn’t miss her, though, fifteen-hand white mare, easy keeper and green-broke.

“Maybe we should get some oats?” I suggested.

“Nah,” Skip said. “Too much like a bribe.”

It was a rocky, forty-acre pasture, and she was turned out with a small band that took off running the minute they saw us. We chased them up. We chased them down. The mare was plump but stout, with terrible withers for a packhorse (Skip said), though she proved her soundness as she ran lightly over the rocks with us panting in pursuit. After about two hours she’d worked up a sweat and stood while Skip haltered her. She seemed relieved to have the chase over with.

She was sweet with big dark eyes and lowered her head while I stroked her damp neck. “Do you like her?” Skip asked me.

“Yeah, I do.”

“Then she’s yours. Let’s lead her down to the ranch and see if we can make a deal with Jim.”

By the time we reached the ranch house, sunburnt and parched, I was eager to come to some kind of agreement. Jim was pretty sure he wanted three hundred and fifty dollars for her. She was young, and, you know, he didn’t really need to sell her. Skip, stuck on paying three hundred dollars tops, finally said, “Jim, Pam would really like to have that little mare . . . how about three hundred dollars cash and a shot of Wild Turkey?”

Jim rubbed the back of his neck, then, looking at our faces, smiled and said, “Okay, get your bottle and you have a deal.”

I named her Pearl.

Three hundred dollars with a Wild Turkey kick turned out to be the right combination for mule trading too when we conducted a similar trade with the Moore brothers for an espresso brown, bright-eyed hinny a couple of days later. Upon delivery, Skip opened the stock-trailer door. The mule stood looking at me. Skip, who had the halter rope in his hands, gave it a little jerk, and she reared up, striking toward him with both front feet. The men laughed, saying, “She prefers a woman!” and Skip thrust me the rope, saying, “She’s your mule, Pam, come get her!” And from that moment on, she was my mule.

We called her Hinny. Hinny is the name given to the offspring cross between a stallion and a donkey. It is hard to get a stallion to breed a donkey, so hinnies are rare and smaller than mules. Skip said the dead giveaway, if you were ever in doubt as to whether it was a hinny or a mule, was the difference in their bray. A mule starts out with a horse’s whinny and ends with a donkey bray, but I could never hear the difference between the two, though I tried.

With the bay and buckskin mares Skip already owned, gentle Pearl, and Hinny, we had our “string.”

Next, we assembled our gear and got organized. From a wooden box Skip withdrew clean and stitched muslin sacks he’d sewn to contain and protect the provisions. We made a shopping list. In Enterprise, we bought flour, cornmeal, oatmeal, popcorn, dried beans, rice, powdered milk, jerky, and raisins. Besides salt and pepper, we packed cinnamon, garlic powder, and oregano. Perishable foods included a brick of cheese, butter, eggs, oil, bacon, apples, potatoes, and onions. A small pottery crock reinforced with duct tape held a sourdough starter for making bread and pancakes. At night Skip sat with his pocket knife, carving a snug-fitting lid from a pine board. He also packed a fishing rod and slung a twenty-two rifle in a leather sheath from his saddle to shoot game birds. We carried no tea or coffee and would depend on wild teas and the fresh water found in most every draw.

The kitchen kit included a small folding grill, a skillet, a saucepan, a coffee pot, two tin plates, two tin mugs, two forks, and two spoons. A grater, a large kitchen knife, and a spatula.

Our bedroll consisted of two green army-issue sleeping bags we zipped together and customized by adding liner sheets and a beautiful Hudson Bay blanket, cream with stripes of red, green, and yellow. He wanted to put snaps on it, to hold it in place. I agonized. “You’ll ruin it,” I said.

“It’s not ruined if we use it, Pam.”

I’d begun to learn that this was his practical waste-not, want-not philosophy. If we needed it, we bought it and manipulated it to suit our purposes without remorse. I’d already watched him saw off the handles on the shiny new pressure cooker. Watched him turn the heel of a sock to the top of the foot when a hole appeared. And eat the entire apple. Seeds, core, and stem.

The finished sleeping bag was roomy and comfortable and took on the dimensions of a large hay bale when rolled, tarped, and tied.

“How are you going to pack that on a horse?” I exclaimed, thinking about the challenge it would be to buck it into the back of a pickup.

“Perfect top pack. You’ll see.” I imagined the growing mountain of gear balanced precariously on the backs of two animals—my sympathy increasing as each new item was added to the pile.

I spent the next week getting to know the animals. Bonnie, the bay mare, was big, powerful, and obviously in charge, alternately bossing the others with laid-back ears and narrowed eyes, then nickering with concern the minute they were out of sight. Candy, the caramel-colored buckskin with black mane and tail, was curious and a little lazy, falling behind on the short rides we took from Camp Creek. Hinny was always on the prowl, tirelessly pacing camp, nervous and inquisitive, and Pearl was a pearl, calm and serene. And finally Puss—every inch of her leaping with life and love—heeling the backs of our boots and weaving love knots between and around us. At night she lay near our heads, silently twitching, sleeping soundly like the baby she still was.

Copying pictures from the Seven Arrows book, I painted shields on the outside of rough plywood gear boxes. A sun, a moon, an eagle. I took my share of guff from the ranchers and visitors who showed up at our camp with nothing better to do than make fun of Skip’s girl. He kept his good humor, and I floated on my little cloud of possibility. Nothing seemed like a big deal until Sam, gruff and twinkly-eyed, came for breakfast. I’d cooked a pot of rice, and when I removed the lid, the rice was green! I looked at it, shocked and humiliated.

“What is that? Maggots?” exclaimed a delighted Sam.

I’d used Rit dye on some white muslin the day before. It was a cheap aluminum pot, and though I’d scrubbed it thoroughly, some remaining residue had bled into the rice as it cooked.

I knew I’d never live this down, and the sooner I came to grips with it, the better.

Turning to Sam, I said, “Would you like a couple eggs to go with those maggots?”

I found out there was a lot I didn’t know about putting gear on a horse. Miles of rope, to begin with. Rope to manty the sleeping bags, rope to hitch around the camp boxes, stake-out ropes, and lead ropes. Then there were knots. The slipknots that released quickly if a horse spooked and pulled back. The lacy pigtail loop that linked one animal to another in a packstring and could be undone with one yank of the rope “tail,” and a couple different methods of tying on boxes and bags, depending on their weight, size, and proportions. There were even special knots for attaching halter ropes to halters, bridle reins to bridles, and one used specifically for tying a horse up.

“The only possible profession with more ropes and knots,” I observed, “could be sailing.”

And finally the lash rope, which formed the diamond hitch and held everything together. Squinty-eyed men who pack for a living can judge you just by looking at the size of the diamond in the center of the pack, Skip told me. “It should be no bigger than an asshole.”

At last, one end-of-April morning, Skip fastened a large Swiss bell threaded on a leather strap around Candy’s neck to help us keep track of the herd during the night, and we were ready. We left Camp Creek with no backward glances—well, maybe a tiny one at the orange Volkswagen now containing my pillow, towel, extra clothing, slippers, flashlight, and wristwatch.

“I’m bringing the dress,” I’d insisted, folding and tucking it next to two contraband pair of underwear.

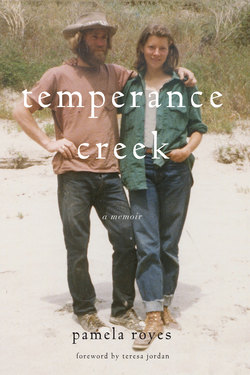

Letter home—April 5, 1976

Dear Mom and Dad,

First and last, I love you and wish you were here so I could give you big bear hugs and tell you how good everything is. I’m going on an adventure! I know it’s no use asking you not to worry, but don’t! By now I think you’re conditioned to expect just about anything from me and hopefully you will be able to accept what I am about to tell you. You know how difficult it is for me to make long-range plans (I know, I’m too spontaneous), but like I said on the phone, I’ve met this guy named Skip, he’s kind of a gypsy himself, and he’s asked me to go down to the Snake River with him. Both of us are tired of traveling alone. Skip has two horses and just bought two more. He’s been exploring this part of the country for a couple years, and we’re headed for a place called Battle Creek. Fishing will be fine and we’ll set bird snares too. I will be gathering herbs to dry and sell in the co-op next fall, and there are all kinds of abandoned fruit orchards we’ll be picking. We have a puppy! Well, we’ll be gone a couple months and I will write whenever I can. Let my friends in Medford know what is happening. I love you, take care, and hope to see you come fall,

—Packer Pam and Sling-rope Skip

The birds were singing as we belted out, “Sixteen ton, what do you get, another day older and deeper in debt, Saint Peter don’t you call me cause I can’t go . . . I owe my soul to the company store . . .” Half a mile out of camp, Pearl’s pack turned completely under her belly.

“Shit oh Friday,” Skip said.

I was dumbfounded. How, with the yards and yards of rope we’d wound around her, had things come loose?

I held Pearl’s lead rope and made soothing noises while he untangled the lash ropes and repacked her, this time jerking the ropes so tight her legs splayed. She “slipped her load” twice more before making camp that evening, and by then I’d memorized the full sermon on why high withers are necessary on a packhorse and the sooner we broke her to ride, the better, especially if we wanted to see the Snake River during our lifetime.

The next day we slipped a few more loads, giving me time to absorb the landscape. Late April in the canyon, the air stirring with secret and enticing fragrances. Sweet cottonwood leaves, familiar, nourishing, and deeply comforting. Delicate scented sprays of white serviceberry. I broke off a bloom and tucked it behind my ear. On the hillsides, emerging wildflowers in creamy yellows, purples, and pinks. Balsamroot sunflowers nodded in passing, nestled among the feathery tufts of bunchgrass, now turning from tan to green in the spring sunshine. Overhead, mashed potato clouds bunched and then broke up, undecided whether to stay or go.

When I asked Skip to identify the wildlife, the plants or trees, sometimes he would say their names, but often he didn’t know or would say I just had to find out for myself.

One afternoon, Skip stopped me, pointing to the base of a large ponderosa tree. “See those marks?”

I rode abreast him and looked. Starting eight feet or so up the tree were deep scratches, about four feet in length. “What are they?” I asked.

“Cougar’s been sharpening her claws here.”

“Do you see one?” I asked, swiveling my head in both directions.

“They’re here, but difficult to spot. Nothing to worry about.” And we moved on.

Once, kneeling, he pointed to a newly shed rattlesnake skin, thin, transparent, and cylindrical, explaining that each time they shed, they added another rattle segment, and to give them a wide berth when this happened as a snake shedding its skin was as cranky as a woman with a sunburn. He said the shaking of the rattle made a sound like a castanet and was your only warning that it was coiled and prepared to strike. And that a rattlesnake could strike faster than the human eye could follow. He said that if they lost a fang, they could actually grow a new one.

I said I hoped to God I’d never see a live rattlesnake. Skip just laughed.

On some mornings I heard a sound I couldn’t identify. It reminded me of a ping-pong ball dropped on a concrete floor. It would begin slowly then speed up. I made guesses. Someone was tapping on a log or cutting wood. A distant motor on the road far below. Something the spring air was bringing on, a conversion of some sort. An insect. A rock rolling in the creek. But I could not discover the source of that sound.

Skip would only say, “It’s the earth waking up.”

One morning while Skip fussed over a skillet of fried potatoes, I heard it again. Clutching the camp shovel I crept up the draw, silently working my way toward the sound. When I heard the sound, I stopped, and when the sound stopped, I crept. Creep, creep, stop. Pong . . . pong . . . pong, pong, pong, pong. Creep, creep, stop. Pong . . . pong . . . pong, pong, pong, pong, pong. There was a little movement in the underbrush, and I saw a bird on a log. The sound was unmistakably coming from this chicken-sized, brownish-gray, wing-drumming bird. I had found the source, by myself, and now I needed Skip to tell me its name. I raced back to camp.

“It’s a bird. I saw it up the draw beating its chest with its wings. What is it? You have to tell me now.”

“It’s the ruffed grouse, trying to attract a female. Good work,” he said with a wink and handed me a steaming plate of potatoes.