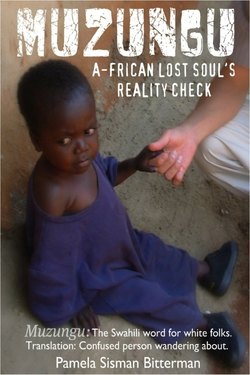

Читать книгу Muzungu - Pamela Sisman Bitterman - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One - Arrested:

ОглавлениеHakuna Matata my Muzungu butt.

Joe Bitterman

“Pami, they’re arresting me,” my husband Joe cautions as I skip over to the security baggage check at the Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi, Kenya. He looks so dapper in his new safari outfit. Except for that twitchy smile hanging off his perplexed face. His head is raked in its customary tilt of contrition. He’s trying not to frighten me.

“Ooh Joey, let me get a picture!” I squeal.

It is eight a.m. on the morning that he and I are to finally fly out of Africa. I have been in Kenya for nearly two months. Joe came over only for the last week to take me on safari. Our daughter is waiting for us in London. Our bags are checked and I am flailing our boarding passes. But we will not be leaving as planned. Instead, we will be placed under armed arrest. Well, Joe will be under arrest, muscled around at gunpoint from airport to jail to courthouse to prison, while I paddle after him. The grinning officers who prohibit me from taking a photo try to cajole me into catching our flight and going on ahead.

“He’ll be all right, mama. He didn’t kill anyone. No worries. Hakuna Matata!”

“Yeah, right!” I blurt out with that twitchy smile now hung on my anxious face.

The following is Joe’s lyrical travelogue of our middle-drawer, six-day wildlife safari, his description of the bizarre scene at the airport, and its ludicrous unraveling: a blow-by-blow, often grisly, sometimes comical, ceaselessly tense horror show of the struggle of my husband and me to keep him from vanishing into an African slammer. It is touch and go. Every scene of the ongoing drama plays like pure fiction too preposterous to be taken seriously. Except it is all too true.

Here is the revealing reenactment of what should have been our sayonara to the Dark Continent, but instead emerges as a decisive sucker punch delivered by my Kenya in all of its confounding, pathetic glory. The events that make up the substance of my story will naturally precede the arrest, but they will set the stage for this final scene piece by piece, like a house of cards.

Joe’s narrative dictated, cleaned up and recorded:

* * *

I call Pami to wish her a happy birthday, her fifty-sixth. Here in San Diego it is actually the day before, but in Mombasa it is already October 7. After listening to her entertaining account of the events of the rainy stint spent in the saturated Tree House the previous night with Ian, our son’s friend and Pami’s traveling buddy, I dive back into packing for my rendezvous with her.

Dressy and casual clothes suited for both summer and winter weather are strewn all over the bedroom. I am not only packing for myself, but I’m also bringing non-missionary type outfits for Pami. She tells me that she is eager to shed the “schoolmarmish” skirts and blouses decreed for wear by women who travel to Kenya to live and work as she has done for the past several weeks. Pam fully intended to follow her orientation pamphlet’s recommendation to the letter: “Pack as though you will be leaving everything behind as a donation.” This will have reduced her to a state of unholy undress, so I’m bringing safari clothes for her as well. Then I need to throw together another bag for both of us for the second half of our trip, visiting our daughter in London and traveling with her on to Ireland.

The entire time I’m struggling to coordinate seasonal separates, our dog Mabel is whining, nose-butting my ankle, and beseeching me with her cloudy old hound-dog eyes. Her nervous drool flies with each violent shake of her shaggy head, sending globs of slobber to cling indiscriminately on African and European ensembles alike. I’m afraid that because the suitcases are out, our savvy pooch knows that I am deserting her. Nonetheless, my anticipation at the prospect of a reunion with my wife after nearly two months apart wins flat out. So in order to complete my allocated task, I turn two deaf ears and one soggy pant leg in Mabel’s direction and carry on.

The following morning I dress in my Safari clothes—a brand new pair of khaki pants and sport coat expressly designed to look worn and ruddy. Little do I know that it will also be my outfit throughout a fateful incarceration. I catch a lift to the airport from Ian’s father in exchange for the favor of delivering more malarial medicine to Ian, who is planning to continue traveling around Africa for several months. My flight schedule is from San Diego to Houston to London to Amsterdam to Nairobi, over a thirty-hour period during which I have a four-hour layover in London where I meet our daughter and leave her the duffel full of Europe clothes. So eager am I to be on an adventure again, and so looking forward to seeing my love and soul mate of twenty-five years, that I do not sleep one wink during the entire trip.

My plane arrives in Nairobi at six a.m. I indulge a momentary stab of concern when I don’t see Pami, but after I pass through the almost-negligible security, there she is. Although she still has the familiar gleam in her eye of the confident and enlightened woman I know, and the swagger of that seasoned traveler whom I married, she is wearing these hideous missionary clothes that make her look like a bag lady and I almost don’t recognize her. We embrace like a couple of newlyweds while we exchange our latest travel stories.

Pami tells me that she spent the night in the airport curled up with her backpack, on a luggage conveyor belt. She and a young fellow from New Zealand who was en route to Lamu, an island off Kenya’s southern coast in the Indian Ocean, shared the thin strip of lumpy rubber. I’m informed that this was likely the safest place for her to have waited for me. Then together we begin scanning the rows of men holding posters advertising various safari groups. Ours isn’t among them.

It is eight a.m. before our appointed safari guide casually shows up flailing a piece of torn cardboard box. Our last name is scrawled across it with childlike determination in bright purple crayon. Smiling pleasantly, our escort, an attractive, stocky, thirty-something Kenyan man, introduces himself as Harrison. He appears to have limited English-language skills. I soon realize, however, that he doesn’t understand our requests for tasks that he wishes not to perform but has excellent comprehension of anything to which he is agreeable.

Within moments of our departure from the Nairobi airport, on the road that will carry us into the poetic Masai Mara, an enormous uniformed African man shouting in Swahili and wielding an equally enormous semi-automatic rifle intercepts us. I’ve only been in the van a couple of minutes (in the country less than a couple of hours), just long enough to stretch my comatose-weary body out on the rear bench. In my sleep-deprived state I feel as if I’ve been transported to a slasher, B movie set. The menacing officer demands that Harrison fork over a hefty speeding fine. Our driver refuses to pay, insisting that his van is equipped with an electronic device called a governor that prevents the vehicle from traveling at speeds in excess of the enforced seventy-kilometer (fifty miles per hour) limit. I’m rubbing my eyes, holding my breath and waiting for the gratuitous screaming, the whizzing bullets, and the splattering blood. Just as the intensely overcharged atmosphere threatens to detonate, Harrison pays up and presses on. As we drive away from the scene he proceeds to lecture Pami and me about the infamous practice by Kenyan law enforcement of squeezing locals dry. Then he commiserates, shrugging, that the police really aren’t paid a fair wage and that extortion makes up the bulk of their salary. He finishes by stating that I’ll need to kick in some money to cover his expenses. Harrison justifies this outrageous assertion by announcing that he was allotted only what the week was expected to cost and now, obviously, he will be short. I suggest he explain his predicament to Sanjay, the owner of the safari company with whom I’d had all my dealings. Harrison vibrates his head, insisting no, no! He cannot do that. So the curious matter is temporarily left to lie, wafting like a foreshadowing stink through the oppressive atmosphere of our transport, which we now suspect of being both speed- and otherwise-ominously governed.

We later find out that Sanjay had to buy Harrison out of prison the morning he collected us from the airport—probably why he was late—because he had been arrested the previous day for the same infraction and had refused to pony up the bribe, which he more than likely didn’t have. When Harrison lamely tries to suggest that this latest fine was actually because I was lying down in the back without my seatbelt on, Pami declares curtly, “No way.” She understands enough Swahili to be certain that wasn’t the case but warns me that I’d better stay buckled up for the rest of the ride to the Great Rift Valley because the Kenyan police are notorious for harsh retribution when penalizing seatbelt violators. This all seems absurd to me. I’ve barely stepped foot in the country but I am already getting an inkling of what the great rift is really all about.

I am thinking that at fifty miles an hour it is going to take us forever to get to our first destination; however the roads are so awful that we don’t average more than thirty miles per hour. I am desperate to sleep during the drive but the steady stream of crater-sized potholes, in conjunction with Harrison’s erratic steering to avoid careening us into them, keeps bucking me off the bench, even with my seatbelt on. It takes us over six torturous hours to get to Keekorok, our first lodge. When I comment on the deplorable state of the road, evidently heavily utilized by safari-goers, Harrison tells me that a French safari company got so fed up with listening to their clients grouse about it that they offered to pay to have the stretch of road paved between Nairobi and Masai Mara. They would only front the dough, though, if it were guaranteed not to first pass through sticky government hands. The Kenyan government flatly rejected any offer with such a proviso and so the road was left as is. “Now the most expensive safari tours fly their clients in small private planes directly from the airport to the Mara. These tourists know nothing of the condition of the roads they are riding high above.” Harrison snorts.

Our driver squeals up to the lodge mere minutes before the dining room closes the lunch buffet and commands that we run to get in line. We obey, ecstatic just to be on solid ground. Pami and I eat and then check into our room. We take a much-needed, and for Pami, decadently luxurious bath, change, and rest before reconnoitering back at the van for the first leg of our photo safari. The Masai Mara is reported to be thick with exotic wildlife. As a matter of fact, most safari companies will guarantee that you will see the Big Five—elephant, lion, rhino, leopard and Cape buffalo. We never do see a rhinoceros. I consider asking for a partial refund, not for the rhino-miss but because of a more critical breach in our vacation contract, the one that materializes later on.

“The Mara,” as Harrison refers to it, has no roads and is vast and dusky, rather like our local San Diego Wild Animal Park on steroids. And the big cats don’t have a separate enclosure. Everywhere you look there are small herds of wildebeests intermixed with zebras. Harrison explains that the wildebeests hang out with the zebras because the zebras are more astute at sensing danger. When the zebras take off running, the less wily wildebeests know it’s time to vamoose also. I would list the animals we see, but you name it and we see it . . . except the rhino.

We arrive back at the lodge by sunset, just in the nick of time for dinner. I’m beginning to get the sense that making it to all our designated meals is pretty important, as if it’s written in our contract’s small print or something. The buffet is again extensive considering that the local people are starving. We have all-you-can-eats everywhere we stay. It reminds me of Hometown Buffet except for the token Kenyan food mixed in here and there. When we get back to our room, Pami is yakking gaily, and apparently loudly, as she undresses for bed, while modeling for me the deplorable state of her underwear. “Joey, look!” she guffaws as she poses in her African undergarments. At the end of every day at the mission, she’d walk fully clothed right into her dorm’s cement shower and begin her ablutions. In a lightning-fast five minutes she would have washed her hair, body, and all her clothes right down to her shoes. Then she’d wring everything out on the rusty spigot and hang the damp items all around the grounds. “Now just take a gander at these panties. They are so baggy I can stretch them all the way up to my armpits!” She does, and we both begin to howl just as we hear a timid knock at the door. When I open it, a wimpy young Brit appears, beet-red and desperate to avoid eye contact.

“Could you lot please be a bit quieter and frankly behave with more decorum? My new bride and I are in the next room and we can hear every word, even the part about the n-n-n-nickers.” He stutters through a trembling stiff upper lip. We apologize and stifle our bubbling hysterics for a good hour after he leaves. I have to wonder what else our prudish neighbors think as Pami describes for me some of the more grisly and immodest Maseno Mission Hospital scenarios.

That night we leave our first-floor, wall-length French doors wide open to the lovely African breeze that brushes across the wide savannah. Only a floor-to-ceiling, king-sized canopy mosquito net separates Pami and me from the Mara. Sometime in the middle of the night—we have no idea what time it is because the lodge shuts off all its power just after midnight to conserve energy—I startle awake to the unmistakable sound of big cat chuffling right outside our room. I have been many times to the San Diego Zoo and I know a chuffle when I hear one. “Pami,” I whisper, nudging her forcefully. “I heard a lion!” She giggles, says I’m having African safari dreams, pats my head, and rolls over. Then we both hear it—right . . . outside . . . our . . . room.

“Jesus!” Pami screams as we leap from the bed. We bounce into one another, trip into our mesh shield and sprint for the doors, slamming them shut and bracing ourselves against the glass in breathless anticipation of the fully expected charge. When nothing happens, we untangle ourselves from the sticky webbing and open the doors just a crack. Flashlight beams are scouring the tall grass like light sabers and excited human voices are whispering, so we cautiously venture out onto our deck. The neighbors on both sides of us are peeking out from their rooms.

“There were lions! Right here!” they report, terrified. “Did you hear them?”

“Oh yes,” I assure them. “I definitely detected a chuffle,” I add with authority. I don’t think they know what a chuffle is, though, because they just blink back at me.

The next morning I am still exhausted and don’t feel like getting up but we have a scheduled drive at six a.m. into the Mara to catch the animals before the heat of the day sends them scurrying for shade. While Harrison chauffeurs us around, he injects random tidbits of useful information. He explains that the spelling of the game park has been shortened to Masai Mara, but the tribe itself maintains its original Swahili spelling with two a’s in the word Maasai. Once again we see and are educated about an amazing variety of animals. On the ride back for the “obscene” breakfast spread, as Pami describes it, I tell Harrison about the lion-in-the-night incident. He shrugs, dismisses me as though I’m some yahoo greenhorn at a dude ranch, and says, “Lions, yes, there are lions.”

I hope we will have some downtime after breakfast but Harrison wants to take us to see the Maasai village. He insists. Pami doesn’t want to go; she has heard from fellow volunteers in Maseno that it is an undignified performance by the tribe’s people that culminates in an embarrassing interaction with the tourists that compels them to pay up. I ask Harrison if it is included in the fee for the safari and he says no but that the money goes to the village children’s school. He makes us feel guilty, so we decide to go, but once we get there he leaves us high and dry, drives off, and tells us he’ll be back in an hour. It is more like two hours before he returns. He does this every chance he gets during the week we are with him and I can’t say that I blame him. He must be pretty uncomfortable with the whole guide-client shtick. I know I am.

Visiting the Maasai Village is really a very informative cultural experience. The Maasai are arguably most people’s archetype for tribal Kenya and they seem willing to play up their reputation as fierce, proud warriors. The tribespeople claim to subsist on a diet of meat, blood, and milk that they occasionally supplement with a mixture of milk fermented with ashes and cow urine. They admit to practicing both male and female circumcision despite repeated intervention by global human rights organizations which strive to put an end to the rituals. The men in their colorful costumes, complete with traditional hand-carved signature ball- headed clubs, obviously cater to the tourism trade. We learn, however, that many tribespeople also now leave the Mara to attend school and to work as guides, guards, or some even as doormen at lodges and hotels.

I feel uneasy strolling around the huts of families on display like circus attractions, so I buy some trinkets. Pami and I have a number of questions for Dennis, the tribal chief’s son and our interpreter. We ask him about all we’ve recently heard: female circumcision, rampant AIDS in Kenya, having multiple wives, and the practice of drinking the milk and blood mixture—you know, the usual. He confirms everything. Before we are allowed to leave, the appointed Maasai dance troupe insists on performing a cultural demonstration for us, complete with the astonishingly high vertical jumping they are famous for. Standing pencil straight with their arms stiff at their sides, the villagers begin bouncing off the balls of their feet gaining increased altitude with each successive recoil until they are springing sometimes as much as six feet off the ground. Pami and I are adorned with traditional beaded wedding necklaces and ceremonial animal-skin hats, pulled into the circle, and forced to prance around imitating their dance steps. It is pretty embarrassing but they have every right to take a jab at us—tit for tat. Then we give them money. Pami explains that this is the standard drill throughout Kenya. The locals are all poor and they both require and request donations. In this particular instance, though, we also are the beneficiaries of a teaching moment, share a cultural experience with them, and are able to support the Masai children’s education. After we leave the village, we embark upon another late afternoon sunset drive into the Mara, stunning yet again, before having to down another excessive buffet meal.

The next morning, following our final drive through Masai Mara, we depart for Lake Naivasha. At this point, we begin to worry that perhaps our safari might get monotonous. Pami had mentioned to me in one of her most recent e-mails just prior to my arrival that she hoped she wasn’t “Africa’d out” by the time I got there. She has been having such a different experience prior to my arrival and it is easy for me to understand how the tourist gig might be rubbing her the wrong way, insulting her new Kenyan sensibilities. But she is happy on safari. We are so grateful to be together and the adventure is still so wide open that I guess we are up for anything. . . almost.

Again, the drive to Lake Naivasha is horrendous, but this one is not as long. Harrison has this annoying habit of pulling over at designated stops, so that in order to access a restroom we have to pass through markets crawling with aggressive hawkers trying to sell their crafts. Pami tells me that actual toilets are a real commodity here. I say, “A commode-ity?” and she snickers without even rolling her eyes. She has missed me. We ask Harrison not to take us through the tourist traps anymore but he says that they are the only safe places to stop, and then he tells us the tale of the massacred tourists.

Apparently a group from Holland got fed up with the pre-arranged stops and ordered their guide to just park along the side of the road so that they could pee. A band of outlaws used this opportunity to jump the bunch; robbing, raping and murdering them all. Pami asks how the thugs knew that the tour group was making an unscheduled stop and Harrison explains that many thieves work in cahoots with shady guides who radio ahead to alert the thieves to the detour. I am quite alarmed but Pami simply shrugs. She has had previous experience with this form of local harassment. Nonetheless, she will later ask around and won’t be able to find any corroboration for this particularly gruesome tale. Whether the story is true or merely a scare tactic to get us to shop, it doesn’t matter. We gladly utilize the funky bathrooms, becoming adept at politely stiff-arming the front line of vendors, like Hollywood starlets charging through paparazzi.

We finally make it to the Lake Naivasha Country Club, again in the eleventh hour and just in time for the last lunch seating. The buildings are charmingly frumpy and the grounds are lush. The property reminds me of a small Catskills-like resort where my family might have vacationed when I was a child. In the afternoon, Pami and I want to go to an island in the center of Lake Naivasha, so we finagle a voyage across this exotic body of water. There are official water tours run by the country club, but instead my wife and I wander down to the dock and snag a snoozing guy with a leaky boat to navigate us to the island. For a much-reduced rate, this `````local agrees to ferry us across, drop us off, and come back to collect us in a couple of hours.

This island is the site where many of the Out of Africa scenes were filmed. Pami and I recognize the country club complex from the movie as well. The animals used in the movie were transplanted to the island during filming and were left there after the project was finished. The second we reach shore, an aggressive local fellow, clearly intent on being our guide, corners us. Pami and I assure him that we just want to hike around for a short time and don’t need a chaperone. He responds that normally he would insist because it isn’t safe for lone hikers if there are Cape buffalo on the island. I believe him as I have heard from Harrison that more people are killed in Africa by Cape buffalo than all the other animals combined. These beasts are reported to be massively strong and will charge at anything, including a safari vehicle. However, once we slip our would-be guide the requisite tip in spite of our not making use of his services, he is perfectly content to let us to march on un-escorted. But he is adamant that he is allowing us to proceed alone only because there are certain to be no Cape buffalo ashore, as the lake presently is too deep for the animals to cross over from the mainland.

Here on the island Pami and I are able to wander freely among the herds of wild creatures, unlike when we are on safari, where we are absolutely forbidden to leave the safety of our vehicle. We ramble for hours amidst hundreds of wild animals. I stand right up next to a full-grown female giraffe that stumbles upon us on the trail, her head poking through the treetops above us like some prehistoric creature. It is by far the most authentic wildlife experience of our safari thus far, but we are still seeking the elusive hippopotamus. On the far side of the island, we come onto a marshy shore. I hear some rustling in the high reeds, so I grab the camera and bushwhack into the thick brush. As I part the reeds, I spot what looks like the backside of a hippo. Snatching a branch, I poke him gently on the rump so that he’ll look at me and I’ll be able to snap a cool head shot. As the beast turns around, I am shocked to see that it is instead a humongous Cape buffalo flailing its massive snorting head, and glaring with furious blood-red eyes. I bolt out of the bog yelling at Pami to “Run away! Save yourself!” I imagine that the monster is tight on my tail fixing to make me one more dead-tourist statistic. But no buffalo emerges from the bush. Slightly wilted, I wait patiently several meters out of range for my devoted wife, who is doubled over in breathless hysterics, to compose herself.

We do finally see hippopotami on the boat ride back to the country club. Our trusty skipper, the sleepy Kenyan with a soggy canoe and a one-lung, asthmatic outboard, offers to ferry us around the island until we find what we are looking for. He assures us that he knows all their hiding spots. We are reticent to harass the hippos once our captain notifies us that they have been known to attack and overturn small boats, and that it’s actually hippos that “claim more lives in Africa than all the other animals combined.” But he ultimately allays our fears by promising that hippos are rarely aggressive in the daylight and only when separated from their young. He further claims that he regularly moves within their pods to fish, as this is where the schools amass to feed off the crumbs dropped by the munching giants, so we are reassured. Although Pami has just been reminded of my incorrigible knack for flashing a come-and-get-me wild animal bulls-eye on my forehead, she by now trusts the locals to know the real deal. She’s game. And we are in Africa.

We find hippos all right; tons of them swimming, sunbathing, rolling, and splashing around in the shallows. All along the way, our tiny craft encounters boats mashed full of smiling tourists trussed up in coast-guard orange life vests, bobbing along in much more seaworthy craft. But Pami and I are eyeball-to-eyeball with the hippos. We reach out our hands and pet them, getting damp from the nostril spray of the mighty and affably unthreatening hippopotamus. And that night, just like the happy hippos, my wife and I enjoy a little rolling and splashing of our own in our room’s beast-sized, claw-footed bathtub. After nearly two months of marginal bathing facilities, any tub can make Pami ecstatic, even the one in Lake Naivasha, where the brown water gets only lukewarm and merely dribbles out of the rusty spigot.

At dawn the following morning, we head out early for Samburu. Harrison says it is a long drive and in fact it is eight rock-hard-road hours long. He expresses concern that we might miss our buffet lunch. Pami explains that we’re pretty carsick anyway and that we’d be fine stopping at a roadside duka (a small kiosk or lean-to selling household basics) for karoti (carrots) and ndizi (bananas). It’s what she’s been used to doing in Kenya. Again, Harrison tells the dead-tourist story and insists that Sanjay will be upset with him if we miss a single scheduled meal. We make it to the lodge just as the staff is dismantling the buffet. So we each grudgingly fill one plate, take it to our seats, and are hurriedly ushered back to stack yet another. By the time we return to our table, a couple of the dozen cheeky monkeys swinging wildly through the open-air lounge have already made mincemeat of it, which suits us just fine.

Samburu’s topography is different from Masai Mara’s. Unlike the Mara with its spectacular Esoit Oloololo Escarpment that forms the western border of the Great Rift Valley, its life-sustaining Mara River, and famous Serengeti Plain, Samburu is a river valley. It boasts an open savannah, natural springs, and a desert scrub habitat. It is also loaded with wildlife and lush vegetation. Although we see many of the same animals in both, there are some subtle differences. For instance, the Grevy’s zebra is indigenous to the area and there are gerenuk that balance on their hind legs to eat from the tree branches. Harrison is excellent at giving us information about the animals. He tells us that he went to university to become a safari guide. It is well into our week together and our driver is beginning to open up and speak about things that matter to him, like politics. Later, I wonder what he would say about the revolution that is on the verge of erupting in his homeland. While I’m in Kenya, I don’t detect a shred of the storm of passion and violence that will soon rend this gentle country apart.

Harrison is wearing a jersey with “Iowa Hawkeye’s Junior Varsity Soccer Champions” emblazoned on it. I am about to ask him who he knows in Iowa when I catch myself, realizing that he probably has no idea what the logo means and that in all likelihood he has never even been out of Kenya. I do ask him if he owns a car, though, and he laughs at me. “Only the wealthy or the crooked have a car in Kenya,” he scoffs. “They are known as the wabenzi, named for the Mercedes Benzes they drive around in.” He also tells us about the Indians who came to Kenya as slaves of the British, worked during the early 1900s to help build the railroad to Mombasa, and ended up settling here. Indians are primarily the local business owners today and seem to be somewhat resented by African Kenyans.

Similar to in Masai Mara, we take early morning and late afternoon drives in the park. Although the terrain is different, the situation with the safari guides is the same. They communicate with each other on their vehicles’ CB radios to find out where the wildlife is. The constant staticky buzz generated by the intrusive boxes creates for me a distinctly off-putting sensory memory of Kenya. Sadly, it won’t be the only one. When there is an animal sighting, the radios come alive with chatter as a couple dozen assorted safari buses charge en masse, boring down through the crisscrossed, tire-matted savannah to jockey with a smorgasbord of manic foreigners from around the globe, who hope to catch that once-in-a-lifetime photo op. It reminds me of sport fishing, when some lucky boat with an electronic fish-finder zeroes in on a big school and is suddenly descended upon by a fleet of waiting vessels that seem to emerge out of nowhere. At one point we queue up in a frenzied gridlock to catch a glimpse of a leopard lounging high up in a tree with its fresh kill, a gazelle. Frowsy, pale heads and camera-clutching hands emerge from the pop-up tops of off-road vehicles, ranging from rugged Land Cruisers to rattletrap Nissans and everything in between. Rush hour in Samburu.

Harrison insists that we visit the Samburu tribe’s village, which we really don’t want to do if it is going to be anything like the Masai Mara experience. I don’t know if he is getting some sort of kickback, but Harrison is persistent. We relent, and it turns out to be quite interesting indeed.

We are told that the two tribes of Samburu and Turkana, with two separate cultures, are co-existing here because one has been displaced by war. The Samburu are more like the Maasai; they speak the same language, wear similarly colorful bead necklaces, and recognize age as playing a crucial part in determining social status within the tribe. The Samburu male circumcision takes place in early adolescence and signals a boy’s transition to manhood. He is qualified to be an elder at around thirty years of age. The females undergo genital mutilation on the day of their marriage, usually around sixteen years of age. In so doing, it is believed that they will no longer be motivated to have intercourse for pleasure and will therefore be less likely to stray from their husbands. There is no such expectation of the men. The Samburu families live in a clutch of huts made of branches, dung, and mud, surrounded by a fence of thorny twigs. These fences are a stunning statement of one of the unspoken horrors of foreign civilization’s intrusion upon the continent. They stand as an appalling testament, a washed-out graffiti sculpture of impaled garbage and commercial debris, discarded trash from supplies dumped on the continent by well-meaning nations, that has blown from god-knows-where across hundreds of miles of African wilderness and left to rot in the blazing sun and rattle in the crazy wind. Pami takes several photographs of this phenomenon. Sometimes only a picture can truly tell a thousand sad words.

The Turkana are similar in appearance to both the Samburu and Maasai, have a similar language, and are primarily herders. They have the reputation of being the most warlike of the three so we figure it is likely their tribe that has been displaced due to conflict. The Turkana also have the interesting distinction of being one of the few local tribes that has voluntarily given up the practice of circumcision. I notice that many of the men bear tattoos and I ask about this. Our guide tells us, “The tattoos denote the killing of an enemy, those on the right shoulder representing the killing of a man and those on the left shoulder indicating the killing of a woman.” Pami and I exchange wide-eyed nods as we proceed to the exit. Again, before we can leave, we are obliged to pay a fee and to buy some trinkets. I make the fateful mistake of buying a wild boar tusk from one of the old women.

“What is this?” I ask.

“It is a warthog tooth. It will bring you good luck,” she answers via our translator. I ask if they had hunted and killed the wild boar and she tells me no, that they only eat their own cow and goat meat. “This was from a lion kill,” she informs me. She wants 20KSh (Kenyan Shillings) but I give her more, five U.S. dollars, actually. She is so grateful that she insists on posing for a grand photo to make up the difference. Harrison eventually shows up to collect us, and as we are leaving the game park he pulls over to a vista point and tells us that we can get out of the van.

“It is safe here,” he assures us.

“What’s up with all those bones?” I hesitate, pointing to what looks like a large elk skeleton and a pile of assorted horns.

“Good for photograph!” he urges. “No danger.”

So we leave the safety of the vehicle while still within the boundaries of the wildlife preserve for the only time during the entire safari. Pami and I pose with our arms around each other as we stare off into the savannah. We both pose with Harrison for our only photos of him. Then I get heady with the freedom and begin to strike silly poses with the horns protruding from various places on my body until Pami scolds that I’m embarrassing Harrison. He actually seems amused, but I knock it off anyway. So we load up, bid farewell to Samburu, and take off down the trail where we instantly come upon a pride of satiated lions snoozing in the shade of a roadside tree. They are not twenty-five yards from where I had just been playing with what had probably been last night’s supper for them. “Jeez, Harrison,” I sigh, shaking my head in disbelief. “Duuuude.”

On our way out of Samburu, we detour for two particularly memorable potty breaks. One stop is at a place called Thompson Falls. Situated at a lofty elevation of over 2,300 meters (about 7,550 feet), the air is cool and crisp, invigorating even. The falls are spectacular. Predictably, the hawkers are here in full force. While standing on a dizzying overlook, we are approached by a withered man carrying a stick with a brilliant, multi-colored lizard clinging to it. He makes us hold it and we oblige because we are happy and feel good and the air is so sweet, like Yosemite in the fall. Then he demands that we compensate him, which we do. On our way back down the trail from the falls and the toilets, a couple of lively young women ambush us and herd us into their craft’s duka. They do have interesting jewelry and small soapstone animal figures so we consent to buy some souvenirs to bring to family back home. As Pami and I are browsing, I show her a pretty necklace made from African stones and she says, “Oh, maybe for Katie (our son’s girlfriend)?” We decide against the necklace and when we finish shopping, we thank the ladies and pay. At this point we have to literally tear ourselves away from them. They are barricading the exit and hanging all over us. Firmly but kindly we push our way through and finish the long trek down to the parking lot with the two women hot on our heels, hands full of trinkets, hollering at the top of their lungs, “For ked-dee! For ked-dee!” They have no clue what they are saying but they caught Pami’s hesitation and glommed right onto us. We affectionately refer to our son’s girlfriend as Ked-dee now.

Our final pee break has us sitting square on the equator. I know this because on our way we have to walk past a man waving an upside-down Clorox jug, cut in half and filled with water. He straddles a chalk line scratched in the dirt. As we watch, he takes a matchstick and drops it in the jug. Once he has reached under to unscrew the jug’s cap to allow the water to spill out, we observe as the matchstick swirls down in a clockwise direction. Then, jumping sprightly onto the other side of the line in the sand, our resident instructor refills the jug, replaces the matchstick, and reopens the cap; lo and behold, the matchstick swirls counter-clockwise. Duly impressed, we pay, pee, and return to the van.

Our last stop on the safari is Mount Kenya Safari Club, which is an impressive historical landmark. The hotel was once owned by William Holden and is filled with pictures of famous 1950s movie stars who had visited in years past. Also hung throughout the hotel are the decapitated and mounted heads of Kenya’s once-hunted, now endangered and protected, wild creatures. The rough stone fireplaces and doorways made of rainforest wood are framed with eight-foot-long, hacked-off elephant tusks. The charming brand of safari that resulted in these types of trophies was quite different than the one we’re on and it is distressing, to say the least, to be surrounded by the aftermath of so much senseless carnage. On the expansive grounds, there is also a hedge maze and a nine-hole golf course. Every room (cabin) has its own fireplace that the porter lights each night and another great sunken bathtub that we of course make good use of. As a matter of fact, we try to utilize everything that is offered everywhere we go. We even try to play golf. The club attempts to assign us a caddy but we really do like to do our own thing, which would be fine had I not lost my only ball in the African rough. Thinking that we obviously must have misplaced our caddy, an apprehensive groundskeeper races to fetch the ball for me, unable to accept that a wealthy, white hotel resident would do anything so undignified as to personally burrow into the bushes to retrieve a golf ball. But of course that’s precisely what I do, speeding to cut off the loping landscaper and diving into the shrubs ahead of him. When my wife, consumed by hysterics once again, snaps a picture of me on my hands and knees with only my rear, clad in jaunty, bright, mango-colored Bermuda shorts, protruding from a patch of deep scratchy briar, the mortified groundskeeper visibly deflates. To make him feel better I tip him anyway, and this seems to alleviate his chagrin.

The club grounds are beautiful in a stuffy sort of way, but the vista of Mount Kenya’s snow-capped peak looming in the background is awesome.

There are lofty, broad-leafed trees thick with colobus monkeys, and green rolling hills of manicured lawns covered with homely, four-foot-tall, prickly-whiskered marabou storks, doddering aimlessly. We hang around the club until noon and then head back to Nairobi to spend our last night in Kenya. We have an early flight to London the next morning. Nairobi is notoriously unsafe, so we stay on the gated grounds of our hotel—an actual Holiday Inn, no less—have dinner, call our daughter, check our e-mail, and take our last African bath.

The next morning, Harrison comes to collect us at seven for our ten a.m. flight out of Africa. At the international terminal of Jomo Kenyatta Airport, he drops us off curbside. It doesn’t occur to me that it might be propitious for our guide to accompany us through the security checkpoint—not yet. Harrison humbly accepts a 7,000KSh tip (approximately one hundred U.S. dollars), which is probably more than the salary Sanjay is paying him for the whole weeklong safari, and we load our luggage on the same conveyor belt that Pami slept on almost one week earlier. After we pass through the scanners, presenting our passports and tickets en route, Pami proceeds ahead to the check-in desk. I am gathering our carry-ons as the security officer behind the monitor motions to have one of our bags sent back through. When it emerges the second time, he addresses me personally.

“Is this your bag, sir?” he asks. When I answer yes, he requests that I open it. As I unzip the bag, he turns the monitor towards me and inquires, “What is this?” and points to a crescent-moon-shaped object that stands out clearly in the X-ray.

“Oh, I know! That’s the wild boar tusk,” I broadcast as I rifle around for the trinket and proudly dig it out to show him. He fumbles in broken English something about not understanding, so he calls his friend over, who is wearing what looks like a police uniform. This fellow stares at my tusk and then calls someone else on his radio. A uniformed woman appears at about the same time that my wife is motioning for me to come over to the counter to show my passport to the ticket agent so that I can receive my boarding pass. I don’t respond to Pami’s summons because I am in the midst of a theatrical pantomime—making snorting noises, with my fingers protruding from the sides of my nose in a sorry attempt to amuse the policewoman, while describing the nature of my souvenir.

“I don’t think you are allowed to have this,” she decides, clearly not amused.

“Okay, you can keep it. But I need to go now,” I respectfully suggest.

“No, you need to wait here,” she orders in a stern voice that is unexpectedly scary. She again gets on her radio and soon there are four armed officers surrounding me. The woman’s supervisor snatches the alleged illicit object, raises it high over her head like a prized trophy, and announces, “You are under arrest!” while commanding me to come with her.

Pami bounces over from where she’s been checking our luggage. “Joey, let’s go. They need your passport.”

“Pami, they’re arresting me.”

“Really? Let me take a picture!” she squeals excitedly.

“No, no mama, no pictures! He must come with us,” the supervising policeman warns with her hands in my wife’s face.

I’m sequestered off in a corner of the room to wait for the official vehicle that has been summoned to deliver me to the police station. Pami has been in this country long enough to know the drill. She squeezes her way into the tight circle of armed authorities surrounding me. “How much?” she asks my suddenly serious, threatening entourage. “We can just work this out here?”

“Too many people now,” the sterner policeman whispers, shaking his head. “I’m afraid we must go to the police station.” Then, and I think purely for effect in front of his cronies, as I have committed not one iota of arrest resistance, he grabs me really hard by the arm and commands with threatening authority, “Let’s go!”

“Wait! I’m coming too!” Pami asserts.

“No, no mama. You go on your plane,” the policewoman with the radio insists, adding merrily as if I were just being escorted to a pit stop at the loo. “He will come soon.”

“I am not leaving without my husband,” Pami declares with her hands on her hips.

“It’s okay, mama. He’ll be all right.” The policewoman laughs at her. “He didn’t kill anyone. Hakuna Matata. No worries!”

My wife adamantly refuses to leave my side and so off we all drive to jail in the paddy wagon, a military-issue type, road-weary jeep with a floppy, faded green tarp that cracks in the wind like a hard slap. I am sandwiched on a bench between the militia. The “warthog” tooth is jiggling on the corroded dashboard like some baby Jesus stick-on or quivering miniature hula dancer. Pami wriggles her way in to sit next to me. With all their bravado, the authorities don’t resist her much. It’s quickly apparent that as many locals as possible want to get in on this sting; four armed guards are obviously not enough to contain the likes of me. Pami has told me that she perceives the Kenyans to be gentle beggars at heart but are also well-schooled in the art of zeroing in on an easy mark. She says that they aren’t typically trying to provoke, just trying not to miss an opportunity to get a survival leg up. My souvenir and I might be the most excellent prospect this bunch has chanced upon all year. Still, I feel like they are being unreasonably nasty to me. Their bullying treatment and hostile attitude are unsettling to say the least. As I am being dragged off, the kind policeman that first called on his radio prior to all hell breaking loose senses my concern and tries to reassure me. “You will just go to the police station, pay a fine, and be back in time for your flight,” he sings out with a confident wave of his hand.

I really want to believe him.