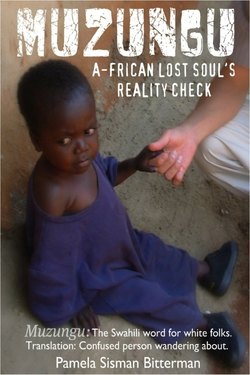

Читать книгу Muzungu - Pamela Sisman Bitterman - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two - Getting There:

ОглавлениеIt is better to travel hopefully than to arrive.

Robert Louis Stevenson

For the record, here is where my journey begins. As an empty nester with an unquenched wanderlust, and at the tender age of fifty-something, I am raring to embark on my next great adventure. Although the world still beckons me as it had in my twenties, when I jumped aboard a circumnavigating tall ship, now it cries out with the voices of those less fortunate. This mother hears that call.

Convinced that I am still able to travel rough and do the difficult work, I conclude that all I need is a people, a place, . . . and devastation. Africa is one obvious answer. It has however, been over twenty-five years since I’ve been an independent world traveler and things have changed. For instance, doors are no longer opened to enthusiastic wayfarers. In fact, I find they aren’t even beat-downable. Helping out in the world——heck, just getting out there—has become an incorporated enterprise, sealed in bureaucracy and bound with endless red tape. I am soon buried in the facts and frustrations of beating my way in, in today’s do-gooder world marketplace. After two years of thrashing through maddening phone calls, frustrating meetings, and a mountain of form-letter-style rejections, what emerges is not encouraging. There is no end to the programs that are positively thrilled to take my money, but this I expected. It is what else I unearth which provokes in me a bone-weary apprehension.

During the last quarter century, a myriad of benevolent vacations have materialized throughout the world that poignantly advertise an outlet for the tourist-with-a-conscience. I am invited to pay a hefty fee for the privilege of participating. I will then be obliged to function under the auspices of—and abide by the rules, restrictions, and carefully protected liabilities that are strictly enforced by—some well-meaning charitable organization that typically has a religious agenda. This modern brand of program offends my independent spirit. Besides, I can’t afford most of them. Such groups try to accommodate me by offering the option of simply dashing off a check, but I have already determined that the guilt-salving spectator’s easy way out is not going to cut it for me. Nonetheless, I have held on to the knee-deep heap of brochures that are graciously sent to me by these groups, and each will receive their well-deserved due. Most also get my money. In the end, my search leads me to the good doctors—Nancy and Gerry Hardison of the Maseno Project in Kenya. We meet. They say, “Just get yourself here.” And I do. The rest is, as they say, history—albeit a rendition unlike any I have yet to run across. My journey should be revealed. It is as rife with portent as many a primrose path tends to be in retrospect.

I begin my search with organizations with which I am already familiar. I am still arrogant enough to assume that getting this munificent venture cranking will be a cakewalk for a candidate as capable and worldly as myself, to say nothing of the fact that I am so keen to sacrifice. The Peace Corps seems like the appropriate first contact. They are front and center in every hellhole on the planet, if I am to trust the news media and Hollywood. Besides, I nearly joined right out of high school. Why, they may still have my application! I suggest that perhaps the agent with whom I speak should have a look.

“Dear. That was like, what, a bazillion years ago? Are you sure the Peace Corps was even in existence back then?” she burbles.

“Yes, dear, it began as a call to action by John F. Kennedy in 1960 and I am a proud child of those sixties,” I enlighten her. “But okay,” I add diplomatically, careful not to alienate her but thinking this is a vital piece of information that was probably in paragraph one of the orientation packet for someone of her pay grade. “I guess the agency was pretty young back then.”

“Yep, pretty young back then all right,” she chirps, adding, “Like you!”

The Peace Corps has changed and apparently so have I, although I am not considered totally without merit. The helpful secretary sends me a pamphlet for the agency’s 50+ program and advises that if I am still interested it will take at least ten months to process my application. If I qualify for consideration, someone will be in touch. I don’t pursue it. I could have, but being so ancient and all, I am in too much of a hurry to wait months to be considered. Anyway, there has to be about a “bazillion” other agencies that are just chomping at the bit to get their hands on someone like me. Moreover, the Peace Corps requires a twenty-seven-month commitment from its volunteers and I am not prepared to leave my family for that long. I figure I’m good for six weeks, two months tops. I’ll keep looking.

Putting out feelers by the bulk-mail load, I realize with dismay that most connect me with fine organizations that contain sticky, non-secular subtexts. It isn’t on this basis alone that I object to them. I simply feel that it may not be in the best interest of these holy-endeavor enthusiasts to invest in someone like me, and vice versa. The underprivileged that we are all trying to help could wind up being the biggest losers. So I search elsewhere.

Next I spend a blissful, deluded interval contacting organizations with a medical focus, hoping that my pharmacist-trained husband will accompany me and that my layman’s foot can slip through the door alongside his professional one. He and I share an impressive travel-bum’s résumé. We had in fact, begun our marriage hopelessly adrift in a life raft in the Tasman Sea in the South Pacific a couple decades earlier, but that is another story. Regardless, I figure he’ll just be in raptures to join me on this new adventure.

“Pami, I’m paying the mortgage, the college tuitions. I have responsibilities, work that I enjoy. Besides, this is something that you need to do. I don’t need to do it. I don’t even want to do it,” Joe gently makes clear.

“Well, you support me, right? You’re not afraid for me to go, are you?” I implore.

“Yes, I support you in this,” he assures me and then with a tender smile adds, “and yes, Pami, I am afraid for you to go. But I know you, and I’m more afraid for you not to go.”

I pursue my communications with the medical groups anyway. Besides having a husband in the healthcare field, don’t I also have a father who’s a physician? Didn’t I raise our own outstanding children and work professionally for years assisting a slew of other families with their kids? I have strong arms in which to hold sick babies, broad shoulders on which distraught parents can cry, and a huge heart that bleeds for the less fortunate. I can be an asset!

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières, the recipients of the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize, is recognized as one of America’s one hundred best charities. They earned a top rating from the American Institute of Philanthropy and an exceptional, four-star rating from America’s largest charity evaluator, the nonprofit group Charity Navigator, the maximum awarded, stating that they exceeded industry standards and out-performed most charities. They reject me, stating in their letter: “We find out where conditions are the worst, the places where others are not going—and that’s where we want to be.” Me too! However, their letter also proclaims that besides focusing tightly on their missions, involving local leaders, and trying to ensure lasting results, they “ . . . don’t venture into areas in which they lack expertise,” subtly suggesting that perhaps I shouldn’t either. Yet enclosed with my edifying brush-off is a form instructing me “how to join.” By filling it out, I can authorize automatic monthly payments from my credit card or checking account and be assured that my contribution will allow their field staff to save lives around the world. My strong arms, broad shoulders, and big heart notwithstanding, I trust them, accept my lot where they are concerned, and send a check. But I am not ready to throw in the bloody towel yet.

Right about this time, I stumble upon an article in our local newspaper about a female physician who is planning to sail with the Red Cross to aid disaster victims of the recent tsunami. The vessel in question is scheduled to depart from our local port. With my trusty Merchant Seaman’s ticket that I earned years earlier during my sailing career, my familiarity with the affected areas, and of course, my fervent desire, it seems only natural to assume that I would be welcomed aboard. Once my work with the ship is complete, the Dark Continent will be an ocean closer and my new credentials earned on an American medical vessel should facilitate my jumping ship in order to aid disaster victims in Africa. Following my phone call to the regional office, the Red Cross representative who I speak to does not even deign to send me a brochure, stating that without specific medical training and expertise, they cannot use me in any official capacity whatsoever.

“Unofficial capacity? Anything?” I take a shot.

“My dear (I am seriously tired of the patronizing ‘my-dear,’ cold-shoulder treatment I keep receiving), it doesn’t work that way,” the phone rep heaves with a superior sigh. “Just ‘wanting to help’ won’t get you in anywhere.”

“Anymore!” I want to assert, but what’s the point? I obliterate the Red Cross from my short list and soldier on.

While scouring the information network for anything humanitarian-related, I come upon an article written by Tracy Kidder about the medical missionary, Paul Farmer and his associates. Within the exposé is a list of groups that are committed to helping people around the world. These groups reportedly “accept volunteers.” The article is entitled, “How You Can Help: You don’t have to be a medical professional.” Half a dozen groups are given brief bios and a Web site is provided at which a comprehensive list of global service organizations can be accessed. I contact every one.

Under the heading, “Get Informed,” three agencies are listed: the World Health Organization (WHO), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS; based in Switzerland), and the humanitarian agency, Save the Children. The first organization, WHO, is the United Nations’ agency specializing in health. I am familiar with them from my first voyage around the world a quarter of a century earlier. Our circumnavigating ship’s crew used the agencies’ information updates via our VHF radio to find out what disease outbreaks had been reported in specific regions through which we were sailing. Typically, however, the cruiser’s grapevine gave us a credible heads-up days or sometimes even weeks before WHO got wind of the risk.

As for the other two organizations, many consider UNAIDS to be the main advocate for global action on the epidemic, while Save the Children has been a leader in health advocacy for seventy-five years, working in several U.S. States and fifty countries to help improve the health, education, and economic opportunities of children and their families. You can’t spit without hitting some form of solicitation or distressing news bite from them in the mailbox, on television, or on the Internet. In fact, I receive a personal invitation from somebody named twebster at Save the Children’s Partners for Children Giving Circle in my e-mail almost weekly. A Charles MacCormack also thanks me personally for my donations. Save the Children has received the InterAction Child Sponsorship certification, has met the Better Business Bureau’s Wise Giving Alliance standards, and has also been deemed a Four-Star charity by Charity Navigator, America’s largest independent charity evaluator. I know my money is in good hands, and that’s nice since money is all that they will be requiring of my hands.

Under the heading, “Get Involved,” the Peace Corps, Partners of the Americas, the United Nations Volunteers (UNV) programme, and Global Volunteers are given special attention. The Peace Corps has sent more than 178,000 volunteers to 138 countries to work on issues ranging from AIDS, to education, information technology, and environmental preservation. In the early 1980s I was asked to write the Peace Corps a recommendation for one of the crew members of the tall ship on which I was second in command. In spite of being a bit of a slacker with a few other questionable character traits, the sailor in question had a good heart and I told the Peace Corps as much. He was subsequently accepted. So I’m partially responsible for the good work done by one of those 178,000.

Partners of the Americas is a non-political network of citizens from Latin America, the Caribbean, and the U.S. who work to improve people’s lives through a grassroots network that connects individuals, institutions, and communities to serve and to change lives.

The UNV has volunteer specialists and field workers of more than 150 nationalities serving in developing countries, as well as working online to translate documents, research data, build Web sites, and mentor young people.

Global Volunteers’ blurb says simply that they are a private, nonprofit organization that has programs in nineteen countries worldwide and that no experience is necessary to apply. Through more in-depth research, I learn that they are also non-ecumenical (not Christian-based). I also learn that is somewhat of a rarity. In fact, the young woman at the agency headquarters in St. Paul, Minnesota with whom I have many heady philosophical phone conversations is a refreshingly neutral, young Jewish woman named Ellen. I grow to appreciate the program and the representative. We become long-distance pals, speak often and at length, develop a mutual respect and trust, and discover avenues of kindred spiritedness. She is reluctant to give up on me and she almost recruits me. I give her huge kudos for that. I am even contacted by someone in my new friend/agent’s office at her behest and am offered a position to travel with them at half price, in a journalist’s capacity. Nonetheless, I cannot justify coughing up the exorbitant fee for a “volunteer vacation” (their words). In the end, instead of sending me across the world, Ellen buys a copy of my first book for her husband on his birthday. I continue on my quest. But in deference to Ellen’s devotion to her program and my newfound belief that it does do good work, I’m going to toot The Global Volunteers' horn here a bit louder.

The Global Volunteers program was founded in the mid-1980s with the goal of helping to build a foundation for peace through mutual understanding. They offer one-, two-, and three-week experiences in Asia, Africa, the Americas, Australia, Europe, and the South Pacific. The volunteers put their energy, skills, and compassion to work in order to benefit others, with the result being a true exchange of ideas, cultures, and understanding. The program is committed to supporting local people in their struggle to become self-reliant, and also serves the volunteers, who learn from their hosts in the process. They advertise that they wage peace and promote justice through an “adventure in service.” They also promise that their volunteers will be reasonably comfortable and safe, but insist that an open-minded attitude is most important—with patience, a spirit of adventure, and a sense of humor thrown in for good measure. I can’t speak from personal experience, but the spiel seems genuine. I say, if you’ve got some spare cash, some vacation days accrued, and you’re not inclined to go on yet another cruise or to party at an all-inclusive beach resort in Cancún, take a crack at this instead. It simply doesn’t fit my bill.

Project Hope sends me a fancy Certificate of Appreciation in grateful recognition of my commitment to the world’s most impoverished people, before I even do anything. The President and CEO presents me with a formal acknowledgement in anticipation of my choosing “to save countless lives” by helping his project “ship vaccines and medical supplies to impoverished communities around the globe, and train people in how to combat disease and improve health.” Hard not to donate once you’ve already received a shiny medal before even doing anything. But they know that.

World Vision sends me a series of mailings with color alerts of increasing import around the world, which are similar to our national security warnings—yellow, orange, red, etc. Scary stuff. My most recent alert is in bright orange and reads, “HIGH ALERT: Over 33 million children are at risk of starvation in Africa. Help now to triple the lifesaving power of your gift.” The words scream at me from the envelope’s cover. Three for the price of one is a dynamite sales pitch.

The next letter is coded in blue and asks for clothes and shoes for freezing children. It promises to multiply the value of my gift thirteen times! And there are pictures. They really get you with the pictures; but again, they know that. One more page gets ripped from the old checkbook.

My husband and I even stumble upon a worthy cause while window-shopping through the local art galleries. One petit new shop displays works all credited to Nelson Mandela. They are intriguing—views from his prison cell, self-portraits . . . rough sketches mostly. We speak to the young female proprietor and to the South African fellow who represents the group that has purportedly finessed the partnership between the art, the man, and the money. Although we leave confused, we aren’t the only ones. An article appears in the local newspaper shortly after, questioning the veracity of the enterprise. Regardless, we leave the gallery with some brochures from a stack at the door. Among them is a largish booklet covered with bright color photographs of happy African children. This one grabs my attention: NELSON MANDELA FOUNDATION, and bears his signature. Nelson Mandela is writing his letter of support as Chief Patron of MaAfrika Tikkun, a foundation that supports various projects in South Africa. The word tikkun jumps out at me. Tikkun is an integral part of the familiar Hebrew phrase, tikkun olam, which means “to heal the world.” In his own words, Mandela describes the project as demonstrating, “ . . . in a practical manner what can be done by limited resources, great commitment and passion . . . Tikkun represents the best of what civil society can offer in partnership with Governments’ considerable efforts.” He concludes his letter by stating, “I would be pleased if Tikkun, through the right levels of support and in particular with monies to assist the payment for its peoples’ skills infrastructure, were to strengthen its efforts to continue its valuable union.” He is “Sincerely” mine, “N R Mandela.” One more check in the coffer. When my husband Joe reads this book, he’ll probably choke. I don’t always tell him how generous we are. But for many years now, at our children’s behest and in their names, we have sent a donation to a worthy cause for each one of the eight nights of the Jewish Festival of Lights, Hanukkah. Compared to the manner in which most families we know indulge their offspring around the holiday season, I’m reasonably certain Joe considers our charitable gifts right-minded.

The Web site, ServiceLeader.org, also provides an “International" link, with a long list of groups attached; all contacted, all researched, all worthy causes, and all deemed a mismatch either by me or by them. And it’s all good. Have a look. We could all do worse in this world.

ServiceLeader.org: International

•All Around the World:

A Collection of International Service-Learning Programs

•Amigos de las Americas

•Amizade

•Cross Cultural Solutions

•EarthWatch

•Ecovolunteer

•Global Citizens Network

•Global Health Corps

•Go M.A.D. (Make a Difference)

•Health Volunteers Overseas

•International Volunteer Programs Association

•NetAid Online Volunteering

•Global Service Corps

•Service Civil International USA Branch

•Students Partnership Worldwide (SPW)

•Teachers for Tomorrow

•United Nations Information Technology Service (UNITeS)

•Visions in Action

•Voluntary Service Overseas

•VolunteerAbroad

•Volunteers For Peace

•Volunteers in Asia (VIA)

•Volunteers in Technical Assistance (VITA)

•Yahoo! Directory of International Community Service and Volunteerism Organizations

About a year into my quest, I am still batting sub-zero. Around this time our son, whom following graduation from university, had embarked upon an around-the-world backpacking trip, returns home. We throw him a party. During the festivities, the father of one of his friends asks me what I’ve been up to. This poor guy has no idea what he is getting himself into. I’m certain he intends the inquiry to be just some idle, give-me-someone-to-talk-to, cocktail soirée chitchat. I give him two earfuls.

“Well, Pam, I know some people in Kenya who will be happy to have you go work with them,” he replies after patiently listening to my agitated whining.

On a self-indulgent roll and still only halfway through my sob story, I stop short.

“Kenya? Africa? You know people there?” I accuse.

“Yup!” he practically shouts. “They are Doctors Gerry and Nancy Hardison. Gerry was my chief resident in medical school. They run a hospital and some program with orphans, I think. Actually, Ian has given some thought to going over,” he advises. Ian is his son and essentially an unofficial member of our family, if the number of meals he’s taken with us over the years is any criteria for unauthorized adoption.

“What do I have to do to go? What’s required? How much? Do you know?” I blather. I can tell by his squinched look that he is working on dredging up the fuzzy details, determined to give me the straight scoop.

“I honestly don’t remember there being any specific requirements. You see, Ian is considering going,” he reminds me.

Ian. I love Ian. Always have. But “Ian going” does not a big thumbs-up for the venture make; quite the opposite, in fact. Ian is a spirited, gifted, twenty-something, sweet, quirky man-child. Our family has had many interesting experiences with him over the years, even attempting some moderately adventurous trips with him in tow. But under the best of circumstances I can only take him in small doses. The rest of our household typically suffers his colossal energy output much better than I do, and Ian is well aware of this. “Uh, I’m gonna leave now. I think your mom needs a little Ian-break,” I once overheard him, sagely and quite accurately I might add, cautioning our son. Regardless, to know Ian is to love him, even if sometimes from a distance. His dad promises that he will have Ian call me with the information. He does not call. He comes, climbs over our deck wall, with dripping surfboard under his arm, and strolls soaking wet right into our living room.

“Hi Pami! Can I have a bowl of cereal?” he announces his presence. I yell at him to dry off, order him to leave his board outside, and then make him breakfast. Between mouthfuls, Ian spews lively tidbits of excited facts about the Hardisons and their program. “I’m going, too!” he announces, grinning through soggy flakes. “We’re going to have so much fun!” Africa . . . an AIDS hospital . . . starving orphans. Fun isn’t the term I’d have chosen to describe our prospective adventure but whatever it is destined to be we are evidently in it together. Truth be told, Ian and I do wind up having fun and more than our share of escapades. But that comes later. First, we have to get ourselves to Africa.

Actually, Surfer Dude hasn’t come over merely cold and hungry. He has also come prepared. Burying his stringy blond head in his funky backpack, Ian extracts a DVD about the Maseno Project, the Hardison’s program in Kenya, and flaps it around like it is a winning lottery ticket. I spread a towel on the computer chair in my office and after Ian finishes eating, we watch the DVD together. I’d be lying if I said there weren’t a few marginally disturbing aspects to the presentation, like little children lined up singing religious songs for the camera. That, along with Nan Hardison’s aggrieved face and her husband’s persnickety one. Ian and I exchange the occasional concerned glance but our excitement dampens any reservations. Ian confirms that the invitation is open. We will be provided with room and board for a modest five dollars a day, and he knows of no real restrictions or conditions otherwise. However, in view of the past months of discouraging research, I am determined to scope it out for myself. I jot down the doctors’ contact information and am surprised to learn that they are presently stateside. They have come back for medical appointments, to do some fund-raising, and gathering of volunteers. For the remainder of the month, they will be ensconced in their little apartment in Ocean Beach, just a couple of miles from my home. I call and we make an appointment to meet.

It isn’t hard to find the Hardisons’ cottage. I am familiar with the area, a green oceanfront community of quaint little batches overflowing with aging hippies and young hopefuls. When I arrive, before I can even knock, a tall, rangy, elderly, but decidedly handsome man in faded dungarees and flannel shirt, opens the door. His startlingly brilliant eyes grab me and hang on as I extend my hand for the formal introductions. “Gerry” (pronounced Gary), he rasps with a flicker of a grin.

“Doctor,” I reply, not ready yet to drop the formalities. “I’m Pam.”

“Um hmm,” he gruffs over his stooped, yet durable shoulder as he leads me into the house. Once inside, I am able to take only a couple of baby steps. The room is a confusion of books, papers, and what appears to be other miscellaneous junk. In the middle of the clutter, an area has been cleared with four chairs—two straight backs and two rockers—placed close together in a semi-circle. An absolutely angelic-looking (no kidding) woman sits rigidly in the more substantial rocking chair.

“Hi, I’m Nan,” she croons brightly but without rising. “Forgive me dear. I’ve hurt my neck and I can’t seem to move it,” she apologizes.

Nan looks to be in her seventies, has shoulder-length gray hair pulled straight back from her face with one of those plastic, faux tortoiseshell half-headbands that came ten to a package for a quarter when I was a girl. She wears a lacy white blouse with embroidered flowers on the bodice and a flowing, full-length, pleated, blazing apricot skirt. On her feet she is wearing scuffed brown, orthopedic-looking old-lady sandals. Her toenails are painted little-girl pink. Her eyes are translucent blue and as piercing as her husband’s, but they have mischief in them that leaps out like a surprise. Her apple cheeks are as red as frosted roses on a cake. Dr. Nancy Hardison looks like a party. I feel drawn to lean in and hug her but she holds me at bay, pointing to the strange, spongy-looking, crescent-shaped blob around her neck.

“It’s filled with warm lavender,” she gushes, “to soothe the tender muscles. Can you smell it?” Indeed I can and indicate so by inhaling deeply and bobbing my head up and down. Then she directs me to sit in the straight-back chair nearest her as Gerry settles into the rocker directly across from us. “We’re expecting another guest,” Nan explains, while stiffly nodding toward the other straight back. “But we should visit, get to know one another until he gets here.”

Just like that, Doctors Nancy and Gerry Hardison have become Nan and Gerry to me. I am hugely encouraged. Anticipating spending an extended period of time in a dark and distant land while being mentored by these fine folk suddenly seems totally doable. But I’m not there yet. I hold my notebook full of questions and my pen poised to jot down helpful hints in preparation for the venture. Nan, however, assures me that she’s seen to it that I receive a form letter with the requisite details. So we relax and begin to chat like old friends. Noting Nan’s lively costume, I inquire what I should bring to wear in Africa.

“Well, not that!” she exclaims with a great deal more gusto than she’s exhibited thus far in the conversation. She is pointing accusingly and rather distastefully at the sweat shorts and T-shirt I’ve worn over. “Women do not show skin in Kenya, Pam. Modest blouses and mid-calf-length skirts are the norm. And you should plan on leaving them as a donation when you leave.”

“Oh, gosh,” I utter, shrinking sheepishly, straining to tuck my long legs, bare practically to the crotch, beneath the punishing chair.

“And they don’t wear pants,” Nan scolds on. “Anyway, skirts make it easier to pee!” she squeals with laughter, wrenching her stiff neck in her merriment. For the life of me, I am lost with this last comment and must look it because she carries on shamelessly. “There are virtually no bathrooms or toilets anywhere,” she elucidates. “We squat over ‘long drops’ in Kenya, deep holes that are natural waste receptacles. It’s so much more convenient to just hike up a hem!” She is thoroughly entertaining herself, I can tell, and it is contagious.

“Well, I’ve brought you a copy of my book, a true story of my sailing around the world. In it, I describe how at sea we used to just heft our bare bums up over the stern of our ship to do our business,” I brag.

“Oh, my. I’ll certainly look forward to reading it. You shouldn’t have any trouble in Kenya then. Not as long as you have a skirt on,” she promises and warns magically, all in one breath.

I feel a little better, although I’m still not sure where or if undergarments fit into the long drop equation. But I figure I’ll have occasion aplenty to find out. As we talk, Gerry sits quietly, lanky legs crossed, wiry arms folded over his chest. And he never takes his eyes off Nan. I begin to wonder if perhaps she isn’t more seriously hurt than she is letting on and that he isn’t more concerned than he is willing to admit. I will learn in due time, though, that this is his normal affect when he is in Nan’s presence. He’ll lock onto her like heat seeking radar. But doesn’t he have anything material to add to the conversation? I wonder. I don’t have to wonder long. Our other guest arrives and the mood in the tiny room alters dramatically. The fairly nondescript young man who settles uncomfortably into the other hard chair introduces himself as a physician interested in practicing global medicine. He is planning to go over to Kenya and do a stint in Gerry’s hospital. He could just as easily have been Santa Claus asking Gerry what he wants for Christmas. It’s not that Gerry gets visibly excited or even shifts his posture or alters his facial expression one iota. It’s just that he begins to talk.

The two men have similar backgrounds and share common interests. They speak the same language. Gerry is in his element. It is as though he morphs into DOCTOR MAN before my very eyes. His attention, like a glowing beacon, is palpable. Realizing that I have not been the recipient of it, I begin to feel somewhat inconsequential. Nan, however, is so welcoming and warm that I allow my shallow wave of insecurity to subside. Besides, once I slip into the conversation that I plan to write one book about my experience in Kenya and put together a second one, a children’s book with illustrations by the orphans, who will then receive the proceeds when the book is published, I notice that both Nan and Gerry’s dazzling, intelligent eyes sparkle like firecrackers. I am going to be an asset!

Nan and I go on to discuss all Kenya- and some non-Kenya-related details. For some obscure reason, the subject of birth control comes up. Nan chortles that were it not for contraception, she’d have spent all her younger years barefoot and pregnant. She and Gerry share a quick but decidedly bawdy, conspiratorial wink. I’m at a total loss to come up with a nifty rejoinder. I have only just met this elderly missionary couple and it is as though I am horning in on some young lovers’ honeymoon. I sit grinning like an awkward teenager as Nan, careful not to wrench her neck again, blushes and rolls with laughter. Regaining her composure, Nan suggests that I come over at the end of the summer, several months off at this point, when the weather is finest. She and Gerry will be making another trip home to the States in October and she states that I will not want to be in Kenya while they are away. I have no idea why. I ask how long she thinks I should plan on staying.

“Oh, at least a month. It’ll take you a week to get over the jet lag and culture shock, then a week to acclimate and figure out what it is you will want to do there. And then a couple weeks to get it going,” she recites as though she has said it just that way a thousand times.

“Figure out what I want to do? Won’t you folks have something lined up for me?” I ask suddenly, not so obdurate about being that arrogant, self-motivated, all-knowing itinerant.

“Oh no, Pam. We don’t presume to tell our visitors what to do,” she sighs, irritably shaking her head like she has also said this a thousand times and is frankly sick to death of it.

“Well, what types of things might I do?” I venture, ever onward into the fray, more fearful of trucking over there clueless and directionless than I am of a reprimand. My staunchly independent journeyer’s resolve is getting shaky, a signpost to which I should be paying attention.

“Don’t worry, dear,” she chirps, transforming mercifully back into the good-witch Nan that I like so much better and need to believe in. And then she utters it, the idiom that will crawl into my psyche and take root there, festering like a cancer: “Africa will tell you.”

It rings ominous but could be interpreted as exceedingly romantic. I decide to go with romantic. I am committed to being committed at this point and it is essential that I have faith. I repeat this saying, packed with every ounce of its implied poetic intrigue and self-aggrandizing import, to positively anyone who expresses the slightest interest in my upcoming venture. The mantra becomes the catchphrase of my experience in ways I could never have imagined. At my urging, Nan recommends a dozen books for me to read in the interim. I assure her that I will and ask if I might not impose upon their busy schedule one more time before they leave again for Kenya so that my husband can meet them.

“Weekends will be best for us,” I explain. “Joe works weekdays as the Pharmacy District Manager for a local drugstore chain.” At this, Gerry’s head whips around like it’s a trout caught fast on a whizzing fly line.

“He’s a pharmacist?” the doctor demands.

“Uhhh huhhh,” I answer tentatively, not at all sure where we’re going with this.

“We would love to meet him!” Nan chimes, all sweetness and light. Up to this point, Gerry has not taken his eyes off his wife for the entire time I’ve been sitting there, not even while deep in conversation with the young physician. But now he is looking dead at me and it is damn unsettling. We arrange to meet again the following weekend. In the interim, I gather and begin to consume the suggested reading material, plus rent relevant films, watch documentaries, and set up future meetings with folks who have already been to Africa. And O Holy Trinity! do I get an education.

Most existing books on the subject of Africa pluck quite successfully at my heartstrings by using a broad range of approaches. Autobiographical texts such as Blixen’s (a.k.a. Isak Dinesen) quintessential Out Of Africa, and Elspeth Huxley’s classic, The Flame Trees of Thika, use a pen to sketch the sub-Saharan landscape in a haze of romantic mystique. Alexander McCall Smith’s delightful collection of fictional stories about the people of Botswana create characters to whom I can relate and sympathize with in an African setting that feels familiar and pleasantly non-horrific. The Poisonwood Bible fictionalizes, via the voice of an American missionary family, what Christianity did to Africa half a century ago. Its message ignites in me a feeling of collective guilt and a gut-crunching dread of ever going over there. As does Paul Theroux’s Dark Star Safari, except that he compares his present-day experience on the continent to a previous venture several decades earlier, consequently assailing me with an exhaustively bitter but brutally honest summation. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is perhaps the fictional prototype for this harsh approach and its subsequent aversive reaction. The Constant Gardener by le Carré creates foreign intrigue in an all-too-believable scenario in which the corporate, predominately white, world selfishly visits unspeakable evil upon third-world people.

The film industry is also popping out stories of this genre like popcorn—Blood Diamond and Catch a Fire, to name a couple. They make for stirring, emotionally gripping theatre, but one cannot judge a book by its movie. Hotel Rwanda illustrates vividly what the tribes in Africa are doing to each other, while Black Hawk Down melodramatizes what American military forces have unsuccessfully proposed to do about the unrest. The Last King of Scotland reminds us how deftly African leaders can turn on their countrymen and dispose of hundreds of thousands of their own. Finally, there is a plethora of appalling personal accounts by Africans detailing the dreadful treatment they and their brethren have received at the hands of foreigners. When I can stomach them, I find they are indisputable records of immeasurable historical importance. The new docudramas such as Tsotsi, which don’t allow us to look away from the reality that remains for today’s indigenous African urban dweller, move me to tears.

There are the heaps of photography books, those that mostly take aerial shots of wild animals, such as Robert Haas’s spectacular collection titled Through the Eyes of the Gods, that make me want to go on safari, or those that concentrate on the ravages of disease, poverty, starvation, war, and genocide that make me physically ill. Wangari Maathai won a Nobel Peace Prize for Unbowed, an unflinching memoir of oppression, perseverance, and hope in her native Kenya. In addition, there are the vacation books, formulaic travel agency fodder, but I don’t even venture there. I advise anyone desiring to experience real Africa, not to either.

Hollywood is literally and figuratively all over the map with the Dark Continent and they aim to pluck my purse strings. From Oprah to George Clooney, Angelina Jolie to Madonna, HBO to CNN, Bill Gates to U2’s Bono. But starlets like Audrey Hepburn, Shirley MacLaine, and Liza Minnelli one-upped them fifty-some years ago, venturing over to aid poor Ethiopian children in Africa long before it was in vogue to do so. There are brochures advertising the dozens of religious charitable organizations with their hands out, along with a smattering of non-ecumenical groups. Then there are the governmental and non-governmental organizations, the grants, fellowships, and philanthropists. Africa’s plight is discussed on the floor of Congress and at the G-8 summit each year. I can’t help but gag on the grisly need, while feeling bloated from the force-fed horror. Mercifully, I have practical matters to attend to while inputting all this distressing data and my mundane preoccupations prove to be an essential distraction.

It is imperative that before I can jet off to the backside of the globe for an extended period of time, to live in an impoverished and disease-ridden, third-world country, I have to be reasonably confident that everything and everyone at home will be hunky-dory in my absence. To get my maternal ducks in a row, if you will. My husband has already given me his blessing. Now I just need to have my household responsibilities covered in my absence. Our children are alternately proud and excited for me but concerned about my well-being and their dad’s loneliness while I’m gone. I promise them we’ll all have many long, reassuring heart-to-hearts prior to my departure. My eighty-six-year-old father is facing open-heart surgery and there is no way I’ll take off for parts unknown until I know his condition is stable. That’s about it. Well, that and the fact that I want to generate the funds, by myself, that will be required for me to take this journey. This desire is less a financial necessity than a personal imperative. I need to feel that I am assuming this risk on my own. Being a writer is an a-vocational enterprise until you get published, sometimes even then. I do not want to add any additional strain to an already thinly spread family budget.

I place an ad in the paper for my services and am quickly contacted by a family who needs assistance. These folks have a parent, an elderly, retired scientist from the local oceanographic institute who is struggling with dementia issues, mostly forgetfulness and intermittent episodes of uncomfortable confusion. I begin to spend mornings with this fine gentleman, making him breakfast, reading the paper with him, urging him to tell me stories from his glorious past . . . to remember. We become friends and I honestly believe that I get as much from the relationship as he does, maybe more, as he soon forgets my name and why it is that I magically appear in his kitchen each day. Through his pension, the family is able to compensate me. So in that respect I am set.

Next I need to secure my airfare. I assume that since I am getting several months’ jump on the departure date, I’ll be able to find deals. As it turns out, there are no deals. This is Africa we’re talking about, not the French Riviera, and $1,800 is the best rate I can find. My husband and I have one major credit card and it gives us frequent-flyer miles on one airline. As anyone who has ever tried to use his or her miles to fly free will tell you, the evil demon “black-out dates” eat up the bulk of any given calendar year. Consequently, my family has amassed a steamer trunk of unused miles, enough to actually get me all the way to the Dark Continent and back gratis, if I can find someone to choreograph the logistics for me. Subsequently, as anyone who has ever tried to use their frequent-flyer miles will also tell you, getting an agent to speak to you civilly in English in complete sentences, let alone not forsake you for one entire afternoon, is nothing short of miraculous. Booking agent Sue at Northwest Airlines, as promised, I proclaim to you, “YOU ARE MY HERO!” This superhumanly patient woman spends hours on the phone with me piecing together what will constitute a roundtrip airplane ticket from Los Angeles, California to Nairobi, Kenya solely with frequent-flyer miles. Three days, four countries, and five flights, and I am going to Africa. She even manages to get Joe’s flight to join me some months later half-covered as well. We should be careful what we wish for.

Then I secure my travel insurance, paying particular attention to policies with a clause that reads, “Includes emergency evacuation.” I use International SOS as recommended by Nan because it gives a discount to students. I don’t know why I keep setting myself up for this humiliation, but “You do not qualify for the discount,” keeps coming down the pike at me. I pay the full amount and get the comprehensive SOS Global Traveler package with 24-hour alarm centers accessible worldwide. They’ll even ship my dead body home, thank you very much. Next I begin the process of making sure I am fit for the venture. I schedule the full complement of medical exams. Somewhere in the conversation with my internist, the issue of inoculations comes up. “Well, Pam, what have you gotten and what do you need?” my doctor asks me.

“Dunno,” I shrug.

“Dunno what you’ve gotten or dunno what you need?” he teases, somewhat earnestly.

“Both?” I answer, embarrassed. I am a bear where my kids’ health is concerned, one of those mothers from hell who is a physician’s worst-nightmare types. Much to my children’s chagrin, there is positively no part of their anatomy that has been left unturned. But I have lost track of my own personal health assessment, anything not related to my obligatory, annual OB/GYN routine. Truth be told, the bulk of my mass (mass of my bulk?) has been complying with gravity, going with the flow bravely down the path to its inevitable perpetuity. And less has become more as far as close examination is concerned. So I have literally let it slide.

“Well, let’s start with your shot record,” my longtime friend and only cursory personal physician compromises. I am, in fact, sitting on the exam table in his office, fully dressed.

“I’ll come in, but I’m not taking my clothes off,” I tell him. I have one of those irritatingly conscientious health plans where each section of your body is relegated to some medical specialty that has a special department, with specialists that are trained to see that special part of you. But you can’t see the specialist unless your personal physician refers you and they won’t do that without seeing you first. My doctor friend is seeing as much of me as he is going to. But he’s fine with it.

“OK, then I’ll take my clothes off,” he cajoles. “Seriously, I’m sure there’s a butt-load of shots you’re going to need but we should make sure of what you’ve already had first. Can I have your card?” he asks like he’s requesting my dry cleaning stub.

“What card? You mean the little yellow cards my kids have had since they were babies? The ones that they need to present each time they go to a new school?” I ask innocently.

“Uh huh.”

“I have one of those?”

“Should.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, Pam,” he groans, looking puzzled. “What’s the matter?”

“I’m certain that I have absolutely no idea what you are talking about,” I insist and then dodge him with, “Okay, you can’t tell me that I am the only fifty-something, healthy woman out there who doesn’t know that she has a little yellow shot card. And even if everyone else is somehow bizarrely aware of having one, no way could they just whip it out upon request one day while visiting their friend/doctor’s office.” Then I test him, “So what if I don’t have one?”

“We’re going to have to access your past records before you were a patient with this group,” he sighs and then pleads, “You have to request that they get sent over to me so that we can get going on this before you leave.”

I reassure him that I have a few months yet. He tells me he’ll go ahead and set up my referrals to the sacred specialists, enough doctors to treat the ailments in an inner-city hospital’s E.R. Then I can come back and get all my inoculations and prophylactic medicines from him and hopefully be fully dosed and shot up with time to spare.

All my tests come back fine and my ancient history of inoculations is excavated from the tombs of the HMO my family had used for the previous decade. I am up to snuff for general life in the civilized world, having received my diphtheria, measles, mumps, rubella, and polio vaccinations when I was a child—a “bazillion” years ago. But I learn that boosters for diphtheria, measles, and tetanus are currently being recommended. (Polio should have been as I saw its ravages everywhere in Kenya. And we’re just learning that Salk’s neat little vaccine-laden sugar cube that was popped into the mouths of my generation of kindergartners is probably now null and void.) However, I’m told, for “where you’re going,” the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention list inoculations against the full range of hepatitises A to C, yellow fever, cholera, meningococcal meningitis, rabies, and typhoid, as “highly advisable.” I know of no more surefire way for the reality of one’s travel plans to begin to sink in than to begin to sink in syringes that deliver minute doses of nightmare-evoking diseases as well. My internist friend is able to stick me with each one but meningitis. Ian’s father, a specialist in travel vaccinations, is happy to accommodate. And finally, my pal/doc provides me with a grocery bag full of lovely drugs to take along, the full complement of “antis”: antidiarrheals, antibacterials, antibiotics, antihistamines, anti-inflammatories, and antimalarials. Thrown in for good measure are acetaminophen, iodine tabs, hydrocortisone cream, insect repellant with carcinogenic levels of DEET, sunblock with nearly triple-digit SPF, oral rehydration salts, bandages, a thermometer, a fistful of migraine medicine, and more antidiarrheals. Every other word out of this nice man’s mouth is diarrhea. Then I meet Ian’s father at his office and low and behold, Ian is there too. He is so excited he has brought lunch for everyone, even though his dad reprimands him. “Ian, man, I told you no one else wants a sandwich!”

Ian is irrepressible. He chatters on about some friend of his mother’s who is teaching him Swahili. “Pami, you can come too!” As for his travel plans and travel insurance, “Same as yours, Pami!” And the stuff he is collecting to bring for the Kenyan children: deflated soccer balls, tiny surfer clothes, even tinier ‘skater’ shoes. He is stoked. Ian has spent the last year working in a hospital and earning his EMT certification. He fully expects to be of use to Doctor Gerry Hardison and is bringing along all the necessary accoutrements such as white button-down shirts, long slacks, stethoscope, blood pressure cuff, etc. His enthusiasm is boundless and I feel proud to know him. Exhausted, but proud.

My son’s recently retired globe-trotting backpack is going to be my only piece of luggage. It’s pretty hefty but I know if I’m going to get everything I want to bring for the orphans—for example, the flip-flops, crayons, notebooks, candy, etc.—I am going to have to pack very conservatively. I plan to bring only a couple pairs of cotton panties, a couple sports bras, two pairs of flip-flops, one set of long johns, one sweatshirt, and one of my husband’s old work shirts to sleep in. I’ll travel in my roughing-it expedition uniform, which is comprised of my worn fatigue-type pants with many deep pockets, light white T-shirt, and bright yellow vest. Then I’ll have those items there with me as well. But I still need my daily-wear costumes, the modest outfits that were firmly suggested by Nan. Keeping in mind that I am to pack as though I am leaving everything behind, I know precisely where to do my missionary-attire shopping.

The drugstores whose pharmacies are under the supervision of my husband always carry a random rack or two of what look like old hippie-style separates like psychedelically hued peasant blouses and long flouncy skirts. The fashion has never been my best look but I know it’ll be perfection for Kenya—lightweight, cool, compressible, cheap. I grab three or four of both tops and bottoms without even trying them on or matching them up. Who will I be dressing for? The total damage, with my husband’s employee discount, is a whopping forty dollars.

My checklist is getting checked off. I have the basic necessities covered. There are other details I could obsess over, more material I could learn, extra gear I could bring. But I imagine that I’ll be able to make do with what I have or grab what I need on the fly. I feel pretty good to go! Even my faculties are sharpening into adventure mode. The daily exploration of unknown territory and the deciphering of mysteriously encoded exchanges with my mental-acuity-challenged morning companion is helping to inure me to the intellectual demands I’ll face while living as a stranger in a strange land. And my old gumption that has been busting a gut to get loose for a quarter century is now ever present, even at three a.m. when I lurch wide awake from my warm bed in a cold sweat and blurt out, “What the hell am I thinking?” It’s not that I’m having serious personal reservations. It is simply that moms tend to worry that their families will implode without them. As it happens, I find that I am not in the least fearful for myself. In fact, I discover that I’m as game as ever to take this next leap of faith. The “yee-hah!” exhilaration of climbing out to life’s edge has never entirely died out in me. It’s merely been lying dormant beneath a meticulously constructed, implied housewife persona, a twenty-five year stint of nurturing-mother prioritizing for which I have absolutely no regrets. Everything has turned with the seasons, as they should. And a bygone time has finally come back around, although to what purpose under heaven remains to be seen.

That being said, this go-for-it attitude of mine does pose a psychological incongruity that I do have some measure of difficulty coming to terms with. I am experiencing a powerful, altruistic desire to “go help starving children, be a blessing in the world, touch just one life,” with a hefty side of, “travel, have an adventure, get out there, prove you can still do it,” purely selfish thrill-craving. Like a cup of warm milk with a Wild Turkey chaser. I don’t want to go without my husband but I want to know that I can. I don’t need to fly halfway around the globe to be benevolent but I do need to get back out into the big world. I have no concrete conception of what I am moving toward but the lure of the unknown pulls me like an old familiar drug. There is nothing in my life to escape from and yet the passive act of staying put evokes despairing thoughts of, “Oh, if this is all I’m going to do, then just shoot me now!” Some things never change. This is still the same me, just me a little older, me a little slower, me jetting off to Kenya . . . with Ian.

I have to say that having one of my children’s schoolmates in on my personal journey of self-reinvention wasn’t in my blueprint. I fear Ian will disrupt my somewhat anal and scrupulously economical organization. I am packing the bare minimum, just what I think I can get by with; for example, one handful of laundry tabs, one small two-in-one bottle of concentrated shampoo/conditioner, one bar of soap, one package of antibacterial wipes separated into several neat little plastic snack bags, and one box of energy bars. One! I envision Ian bumming a tab for his rank clothes, a dab for his cruddy hair, some suds for his grimy bod, a swipe for his germy mitts, a bite for his grumbly tummy. And will I deny him, scold him for being unprepared, admonish him for being selfish, berate him for blowing my cover and outing me as “the mom person” I am endeavoring to leave behind? Never. I am resigned and actually curious to discover how it will all play out between us. When his folks implore me to please look after Ian for them, I tell them that we will look after each other, figuring that I can at least keep myself off the liability hook to that extent. Truth be told, Ian and I do look after each other. We both prove to be ready, savvy, daring, caring, and gung-ho—intrinsically different, independent explorers embarking on a journey to discover our separate ways—together. And what grander venue could we dream up in which to have at it than extreme Africa.

The Dark Continent looms outrageous and I find we are not permitted not to be outraged. The media blitz has played on this brilliantly. Case in point, I gamely truck on over to a little godforsaken corner of Kenya. Enter my story—timely, unique, honest, important, shocking, and first-person true.