Читать книгу Grizzlies, Gales and Giant Salmon - Pat Ardley - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSettling in at Addenbroke Lighthouse

“Are you going to the lighthouse with George?” George’s mother anxiously demanded of me.

His mother was a formidable slip of a woman to whom I would have to prove myself many times before I would be considered part of the family. Her imperious voice brought a sudden hush to those who had gathered to celebrate his mom and dad’s thirtieth wedding anniversary. The crowd parted like the Red Sea, and I was left to stand looking straight across at George’s mom on the other side of the kitchen. We were gathered at the Vancouver home of George’s sister, Marilyn, and her husband, Phil. It was my first time meeting his parents. The silence became palpable as everyone inhaled and waited for my answer.

“Yes,” I said. “I am going too.” Little did I know that I should have been the one who was concerned about heading into the wilderness with George.

George had been fascinated with lighthouses since an early age when his family travelled to Vancouver from Vancouver Island, passing a lighthouse just outside of the Nanaimo ferry terminal. Then years later he hiked the West Coast Trail on the wild, west side of Vancouver Island with his little brother, Jeff, from the Big Brothers organization. He renewed his fascination while speaking with the lightkeepers at the Pachena Point Lighthouse. Not long after, he saw a lighthouse-keeping job listed in the newspaper and decided to apply. It was a few months after our car-rally date that the government called to tell him they had a posting for him. At twenty-seven, George was quite happy at his architectural draftsman job but was looking for adventure. We both thought it would be fun. This turned out to be quite an understatement.

We were scheduled to leave in early April of 1973 for the Addenbroke Island Lighthouse, some three hundred miles north of Vancouver, to become junior lighthouse keepers. I arranged for a friend to use my car while we were away, and George made arrangements to sublet his apartment. There were a number of going-away parties for us, and we said goodbye to our friends with lots of music, dancing and delightful toasts. We actually said goodbye several times, as with most things governmental our travel schedule moved more slowly than planned. By the third going-away party, George was treated to an enormous, beautifully decorated cake in the face. At that point our friends may have been thinking that we would never leave.

We booked into a motel in downtown Vancouver and were there for two weeks before we finally watched our belongings being lifted onto the freshly painted Coast Guard ship that would deliver them and us to the lighthouse. We climbed on board at 10 AM but in typical fashion we didn’t actually leave until about 1:30 PM. The ship zigzagged around the harbour as the crew set their new compass so we wouldn’t get lost if we ran into fog on the way. We finally departed from Vancouver and headed out past Lighthouse Park then turned northwest out of Burrard Inlet.

Immediately the ship began to roll, and it didn’t stop rolling for the next four days. I sat nervously holding onto a container that was strapped to the deck as I kept my eyes on the distant horizon. We left Vancouver behind and with it, all of my conscious experience with civilization, friends and family, stores full of wondrous things, and cars—all things that I would never again take for granted.

We travelled up the Strait of Georgia and passed miles and miles of shore that rose up into stunningly beautiful snow-capped mountains, miles and miles of tree-covered islands and very little else. No more cities, no towns, no crowds of people—no people! Really, no people! Except for the eight men running the ship, we were already in wilderness.

I knew nothing about coastal wilderness. My elementary school years were spent on the wide-open spaces of the Prairies, and my high school years were spent shopping with friends, eating in fancy restaurants and partying. George would be better equipped since he inherited his dad’s love of tinkering with wood and motors and his aptitude for fixing anything and everything.

The West Coast of BC is so rugged with jagged rocky slopes and heavily timbered mountains, occasionally broken only by water tumbling down, that there are very few places with enough open and accessible land to settle a town or village. We cruised quickly up the Inside Passage, manoeuvring through islands, then sailed up Johnstone Strait and past the Broughton Archipelago. Past the Storm Islands and Grief Bay. Then the ship angled right and came out into the open water of Queen Charlotte Sound just beyond Cape Caution. The names of the islands and bays are an indication of what the weather is often like in this region. It’s all true. Terrible storms, hurricanes and gales rage around the area for much of the winter and sometimes even suddenly out of the blue on an otherwise lovely fall day. I can attest to it all from the experiences that I gained from my new life of adventure.

We headed into Fitz Hugh Sound as we passed the entrance to Rivers Inlet, and eighteen miles north of it we approached our new home, Addenbroke Island—but kept sailing right past it. My heart sank. Apparently, dropping us off was not the skipper’s first priority. Many dark hours later and, no doubt about it, many more tree-covered islands later, we docked at Prince Rupert in the wee hours of the morning and stayed the rest of the night—hallelujah!—in a hotel near the docks.

The next morning the ship was loaded with supplies, and later in the afternoon we finally boarded again and headed back down the coast toward Addenbroke Island. The ship stopped at other lighthouses as we travelled south and delivered freight, groceries and a bag of mail for the eager people living there. This was a time-consuming venture requiring all hands on deck, the ship’s crane, straps and nets, and lots of yelling. George and I spent two more nights on the boat in a tiny little cabin with tiny little bunk beds and an even tinier washroom. We ate meals with the crew. The food looked delicious but I was feeling queasy with the constant rolling of the ship and was not able to enjoy any of it. Mealtimes were especially trying when you had to hold on to your plate of food or it slid across the table to the fellow sitting opposite you. Really, I just wanted to shut my eyes and roll up in a ball in my bunk. After the second night and day of travelling south, we were finally getting closer to Addenbroke again but also running out of daylight. By the time we could see the light from the tower, it was too dark to safely get off the boat and onto dry land with all our belongings. Because there was no dock and the little bay was not well protected, the ship anchored in Safety Cove across Fitz Hugh Sound, within sight of the lighthouse, but oh so far away. Safety Cove is perhaps best known as a place where Captain George Vancouver beached his ships for a time when he was exploring the West Coast in the 1790s. We spent another claustrophobic night on the ship.

Early the next morning our ship chugged over to Addenbroke. Once there, we climbed down a precarious ladder on the side of the ship and into a bobbing rowboat and then rowed to the shore right below the wharf. The ship’s men used the crane to off-load our furniture and boxes of goods, plus supplies for the senior lightkeepers. They were also delivering the newfangled automation equipment for the light and horn. The Canadian government’s plan was to automate all the lighthouses over the next few years. The senior keepers were not pleased to see this equipment arrive because they thought of the island as their home and didn’t want to be made redundant once the island was fully automated. (They need not have worried—I am writing this forty years after the fact and the island still has lightkeepers!)

There were two houses on the island, one for the senior keeper Ray Salo; his wife, Ruth; and their preteen daughter, Lorna, and the other for the junior keepers. That would be us! The junior keeper’s house had two bedrooms, a very large kitchen and a great living room with a window that covered almost one whole wall facing west toward Fitz Hugh Sound and across to Calvert Island several miles away. We could see snow-capped Mount Buxton perfectly framed by the huge window and a waterfall cascading down into the ocean. People could travel all the way up the wildly beautiful coast in a boat, anchor in the bay, walk up the boardwalk to our house and still, they couldn’t help gasping at the spectacular view from our living room.

From the kitchen window we could see south to Egg Island about twenty-five miles away, and on a clear day we could even see the mountains at the north end of Vancouver Island a little over fifty miles away. Beside the big front window was a door that led out to a huge square deck. The deck had been built on the base of the site’s original lighthouse, which had been pulled into the sea by ships’ winches in 1968 to make room for the new lighthouse and tower on top.

The house was fantastic! We loved it, but there was one little problem. The fridge was missing. We had nowhere to store our fresh produce. Somehow that important detail was not included in the memo from the Coast Guard about the contents of the house. We got to work and made ice in the downstairs freezer and made do with a cold box until a fridge was finally delivered many months later. And, there was more than one problem. There was also no washing machine, just two sinks and no dryer either! Something about the 7.5 kilowatt Lister Petter generator (our only source of power) not being able to handle too many electrical appliances, especially those producing heat. There was a note in the memo that said, “a drying rack of light rope would be very useful indoors.” How nice that the previous occupants had left a clothesline outside that we could … I could use. There was also a note for us to apply for and bring with us a cncp Telecommunications credit card so we would be able to send telegrams. Otherwise we would not be able to send quick messages to family while we were stationed there. We would receive mail about once a month when our groceries were delivered. On top of it all, there were no curtain rods or curtains so we lived without for the next year and a half—but given the wilderness setting, who needed curtains?

In the basement there was an oil furnace, which we would be grateful for when we saw how much work it was to keep the wood-burning furnace going in the senior keeper’s house throughout the winter. There was also a workbench attached along one wall, and we immediately started planning which woodworking tools we would buy once we had money. The basement also had plenty of space for storing extra food supplies. We were told to have no less than two months’ worth of groceries on hand at all times.

Half of the basement was a water cistern that held fresh rainwater that washed off the roof. There was a pressure pump to push the water upstairs. There was no other water source on the island so we quickly learned to conserve the precious liquid. No leaving taps running while brushing teeth, or washing dishes under running water. Ruth told us the scary story about some lighthouse people who ran out of fresh water many years before and had to have water delivered from a dirty, rusty tank off the Coast Guard tender boat. We were having none of it. To this day I can’t leave a tap running for more than a few seconds.

Addenbroke Island is about two miles square, with the houses on a cleared area on the Fitz Hugh Channel side with enough area in front of the houses for two lovely, though time-consuming lawns. Other than the gardens and walkway areas, the rest of the island was covered with a thick forest of huge cedars, yew, a few small shore pines, spruce and alder as well as dense salal undergrowth—but mostly cedar. The bay was only safe to anchor in if there was good weather, which was rare in winter, and there was no safe place to build a dock because of the constant crashing waves. Instead, a wharf was built far above the high-tide line. The wharf was about 150 yards from the houses. There was a small rowboat that belonged to the station and an even smaller skiff, with an ancient motor on it, that belonged to Ray. A hydraulic derrick on the wharf lifted the small boats in and out of the water when they were needed. Halfway between the house and the wharf was a fenced garden on one side of the walkway and a short path that led through the salal bushes to the helicopter pad on the other. When it was convenient for the Coast Guard, they sometimes arrived in a helicopter between the regular monthly boat deliveries and brought our mail. And if we were notified in advance of their delivery, which was seldom, they could bring a little extra fresh produce.

Ray and George split the twenty-four-hour workday between the two of them with Ruth covering a few hours in the morning while I took a turn late in the evening to give George a chance to have a nap. During my late-night shift months later I heard a song dedicated to me on a Seattle radio station, the one channel that our radio could pick up. It made me feel like I was still connected to the outside world. The fact that I was the one who had submitted the song request to the station (by mail) meant little. Even if it was a dedication to myself, I heard my name on the radio!

George worked from midnight until 4 AM and then 10 AM to 6 PM. Ray and George worked together in the afternoon on a variety of projects to keep the lighthouse looking good and functioning well. They made repairs wherever they were needed; they painted the white buildings and the red trim, cut the grass and maintained the machinery. They worked inside if it was raining and outside if it was dry. During the day I could always hear Ray talking while they worked. Ray had a wealth of knowledge about life on the coast. He was patient and helpful and always explained how something worked or how he wanted the job done. George soaked up the information like a sponge. Ray was like a little old elf, small but agile as he moved quickly and clamoured over rocks and up and down ladders with ease.

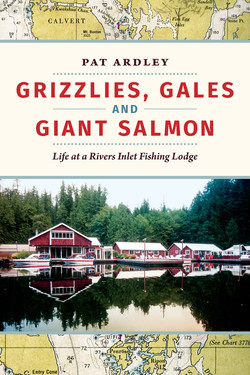

Me with the Addenbroke Island light tower in the background. Having moved from the flat, open spaces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the rugged wilderness of the West Coast, I was ready for adventure. I think I got more than I bargained for.

Part of George’s job was to, once a day, radio the weather to the Coast Guard in Prince Rupert, including wind speed and wave and swell height. And at 6 PM he would take the Canadian flag down. The main duty for the middle-of-the-night shift was to keep an eye out for fog because the keepers had to go out to the generator room to manually start the foghorn if visibility went down to about two miles. The horn had a lovely deep-throated bellow that was easy to get used to. I could drift off to sleep feeling safely wrapped in the fog on solid ground while the sound of the horn washed over me.

George and I spent a lot of time talking. There is nothing quite like being stuck on an almost-deserted island on the Pacific for couples to learn how to communicate with each other. Who needs couples therapy when you have endless hours in front of you with no one else to talk to but your partner? We talked about anything and everything. We talked through our arguments, we talked over our finances, we talked about the past and we talked about the future, always with me curled up in the cozy armchair and George sprawled on the couch so we could both watch the changing scenery through our awesome front window. There was nowhere to go, so we learned a lot about each other. I thought of the saying my mom would quote to us kids when we were having a tough time: “What doesn’t kill you outright, will only make you stronger.” We decided that rather than killing each other outright, we would make the most of our life together on the lighthouse. We only got stronger.