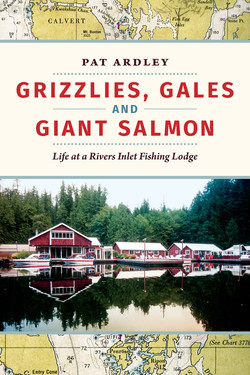

Читать книгу Grizzlies, Gales and Giant Salmon - Pat Ardley - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеExploring the Wilderness

George liked to get away from “it all.” One day we headed out hiking and I found that it was more like slogging once you were about six feet into the bush. There was a lot of heavy coastal underbrush, mostly salal, amongst the towering spruce and cedar trees. Huge trees had fallen over the years and were hard to climb over or under. Occasionally we had to scramble straight down ravines and then straight up on the other side, clutching at little clumps of roots, young bushes or sometimes prickly young spruce trees to steady ourselves. We then came to an area that was impassable. We couldn’t go up or down or over or under and had to turn and claw our way back to the water. We were sort of swimming across the top of the thick salal, our bodies far above the actual ground. I had been so hoping for an easier route back to our house and its lovely expanse of wide-open green front lawn. We finally “swam” our way out toward the edge of the island, which at this point was a rock face, straight down to the water with a thin ledge about sixteen feet above the rocky beach. Waves were crashing and swirling on the rocks far below.

George could see how nervous I was, and said, “Trust your boots. They have a good solid sole and will keep you safe.”

I stared down at the thin strip of rock cliff that was little more than half an inch in width. I was supposed to walk back, along this? I would have preferred a skyhook to lift me out of there. I put my foot on the ledge and without letting go of the branch in my hand, I tested my boot by bouncing slightly and could feel that it wouldn’t slip off the narrow ledge. I reached over and found another handhold and brought my other foot onto the ledge. This was going to take a while. I carefully reached again and pulled myself over, one boot and one hand at a time. After I had taken six steps across the sheer face, I came to a vertical crack, a fissure in the rock. It was about three feet deep and narrowed as it went in. Peering into the darkness, I could see a little brown bottle stuck near the back of the opening.

I called George to come back and see what I had found. He worked his way back along the ledge to where he could peer in and see the little bottle. It was in as far as he could reach and he tried to pull it out but it was stuck fast. He carefully inched his fingers into his pocket and slowly pulled out a small knife, then he chipped away at the rock around the bottle. After a few minutes he was able to free the bottle from the crack and gently slid it into his jacket. My mind jumped to the stormy wave that must have carried the little bottle and inserted it into the gap without shattering it on the rocks. Ooops! I had forgotten for a moment that I was still perched sixteen feet above the waves crashing over the rocks below.

Just past the ledge we came to a wider shelf where we stopped and lit a fire with our usual allotment of one match. George had a competitive streak—that I had witnessed before on the badminton court, baseball field and at the bridge table—which meant we always had to light the fire with only one match. We each wore a small backpack on our treks, with a small jar to keep matches dry, water bottles and a snack. On this trip, George carried the hot dogs and I carried a small pouch of flour. George cut branches to spear the hot dogs on and I mixed flour and water to make bannock wrapped around a fat stick. After cooking the bannock, you pulled it off and stuffed the cooked hot dog in. I crushed a few thimbleberries that I picked from the bushes surrounding our ledge and spread the delicious jam on the extra bannock.

I would have loved a refreshing nap but we persevered, tramping through the woods for another two hours before we eventually saw the red roof of one of the houses. Strangely we had gotten lost on this little island. My sense of direction was born of the Prairies, where, in the wide-open spaces, I always knew which direction I was headed because I could always see, or at least feel, where the sun was. Down in the darkness of the forest surrounded by two-hundred-foot cedar trees, I barely had a feeling of where the sun was supposed to be. And George hadn’t brought his trusty compass with him. I was worn to a frazzle. I felt like the cat on the Pepé Le Pew cartoons to George’s Pepé Le Pew.

Ray let us use his speedboat to explore around the island. Addenbroke Island is at the entrance to Fish Egg Inlet. This inlet had not yet been surveyed so it was exciting to poke into all the little bays and channels, feeling like we were the first ones there since Captain Vancouver’s crew. We weren’t though. There were ruins of two First Nations’ villages near a great clam beach. Both villages had been burned to the ground in the early 1930s. There was also a small safe anchorage on the north side of Fish Egg with a little wooden sign that read “Joes Bay” tacked on a tree that leaned out over the water.

At low tide in the back of the bay, there is a waterfall more than three feet high coming from a tidal stretch of water called Elizabeth Lagoon. At some points the lagoon is over four hundred feet deep and about a mile wide so, as the tide falls, there is a huge volume of water that comes crashing and tumbling out through a very narrow gap in the rocks. It’s very impressive to see but you really don’t want to get caught in the lagoon when the tide starts to fall or you will be stranded for many hours. At least until the water calms down around a high slack tide, which is when the high tide changes direction, stops going in or coming out and momentarily stands still so you have a chance to escape the lagoon at last. We almost got caught. But usually George knew enough to read the day’s tide table before we headed out in the boat. Usually, but not always! Huge drifts of thick white bubbly foam pile up along the shore just outside the waterfall from the force of the water churning out. I have always fancied that the bubbles are from the grizzly bears having a bath just out of sight. There is a large grizzly bear population in this vast mountainous wilderness area.

We headed back to the wharf at Addenbroke when it was close to low tide. George stopped the boat near the edge of a patch of bull kelp, where you could see the top six feet of the stem ending in a baseball-sized bulb with its long flat leaves ebbing and flowing with the surging of the swell like streams of mermaid hair caught in the current. I leaned over the side and cut several two-foot-long hollow pieces, including the large bulb. I had read that you can pickle bull kelp, so I was going to give it a try. The most applicable recipe that I could find for the kind of texture I was dealing with was one for watermelon rind pickles in an old pickling book my mom sent to me. I spent days boiling, draining, chopping, brining, boiling again, draining, spicing and boiling again before I was finally able to pack the “pickles” into the sterilized jars. In the end, they were actually quite tasty, and I would eventually add them to my Christmas parcel for my mom and dad, which also included salmonberry tea leaves in hand-stitched muslin bags, our canned clams, my fabulous jelly that I would make and canned salmon from the lovely coho that we were soon to catch.

George’s sister could order a side of beef from a local butcher in Vancouver that she would share with us. The butcher would freeze our nicely wrapped portion and box it up for Marilyn to deliver to the Coast Guard in Vancouver. Our district manager in Prince Rupert told us that we would have to get the captain’s permission to allow this box to be carried on their ship. George checked who the skipper would be for the upcoming trip and learned that it would be the crabby-pants fellow, so it was unlikely that he would grant permission. Also, the boat might have taken two weeks to get from Vancouver to Prince Rupert and might not have stopped here on its way by. In which case the meat would have sat in Rupert for a month before being sent down here. Marilyn’s plan just wasn’t going to work, so we were back to ordering super-expensive meat from Prince Rupert.

We used Ray’s little boat to cross Fitz Hugh Sound and drive up Kwakshua Channel almost to the other side of Calvert Island. There is a narrow slip of land at the end of the channel where Ray said we could safely anchor the boat and walk across to a nice beach. We anchored the boat with an ingenious method using two ropes. George coiled the anchor and one rope over the prow of the boat, then he attached a second rope to the first one and took it to shore when we climbed out onto the beach. George pushed the boat off the beach and when he was satisfied that it had floated to a safe spot, he jerked on the rope in his hand and the anchor dropped overboard securing the boat nicely in deep water. Then he tied his end of the line to a huge cedar tree.

A note about the terminology: Growing up on the Prairies, when I heard someone talking about going to “the beach,” I always thought of pretty, blue, calm, fresh lake water and long stretches of white sand with people lying about on towels and lounge chairs, radios playing the latest rock music and five popsicles for a quarter. People in this wild coastal country call anything between the ocean and the lowest branches hanging over the water “the beach.” It can be made up of mucky mud, broken clamshell, heavy gravel or jagged, barnacle-covered rocks and still be called “the beach.” It was hard to wrap my head around this.

On this beach, there was an old cabin just past the high-tide mark built by people from Ocean Falls about twenty miles away. Anyone was welcome to use it. We followed a trail that led out behind the cabin and crossed the island to the west and the open ocean. The forest here was quite different from the rest of the island, with less underbrush and very large trees but farther apart. It was quite easy to follow the trail between the trees, huckleberry bushes, and barberry and Oregon grape shrubs. We passed a giant cedar tree that had a huge scary mask carved into it that was painted deep red and blue and had a huge pointed nose sticking out. Then a little farther along the trail was a tree that had been bent down and then around so that it grew straight back up. It created an almost two-foot round frame for people to peek through to have their picture taken. There must be thousands of photos of happy faces in that frame. We later learned that a certain Dr. George Darby had slowly and patiently shaped the tree over all the years that he lived in the area. He had been working as a medical missionary based in nearby Bella Bella throughout the year and in the Rivers Inlet area during the sockeye-fishing seasons for over forty years, from his first season shortly after graduating from medical school in 1914 to his last in 1959 when he retired. Many years later the tree was knocked down by an overzealous logger trying to make his fortune with the surrounding trees.

We followed the trail for a few more minutes picking huckleberries as we went, then once again came to a very different type of forest. The trees were smaller and mostly coniferous with old man’s beard moss gracefully trailing from the branches in great long tendrils. The forest floor was covered in thick soft moss with low trillium flowers and tiny lady’s slipper orchids peeking out. The light filtered down through the trees and gave the area an otherworldly feeling. It was enchanting and I half expected to see fairies dancing about. We could hear the waves rolling and crashing onto the beach but couldn’t see water yet.

Over many years, medical missionary Dr. George Darby bent this tree on Calvert Island. The tree is situated on the route to what we called West Beach. Everyone who crossed the island to West Beach had to stop and have their photo taken through the frame.

There was a bit of salal to push through, and then we stepped up onto a log with a clear view of the most magical stretch of white-sand beach and bright blue ocean with waves curling up and breaking onto the sand. It completely took my breath away. The beach was at least a mile long with logs all akimbo at the high points where they had been pushed up by the tide and winter storms. It curved around slightly with rock cliffs at either end. There were several tiny islands with short deformed and gnarly trees a hundred yards offshore. We leaped off the log and ran and ran and ran. I hadn’t realized how much I missed stretching my legs. I felt free and laughed and cried as I ran, the clean white sand squeaking with every flying step.

We then slowed to a stop, turned and stared at the beauty of this incredible place. How could we be so lucky? We hadn’t been told how special this beach was. Just past the winter high-tide mark the beach was lined with low bushes and in a few places there were steep, sculpted rock walls. Along the walls there were narrow ledges with wild strawberries growing as if someone had planted them there. The bushes were all slanted away from the water, and the trees beyond them were beaten, twisted, gnarled and pushed in that direction by savage winter winds. Tall grasses were growing high up on the beach with purple beach peas and bright red fireweed safely tucked in amongst them. Lanky columbines, yarrow plants and huge cow parsnips grew above the tide line. About halfway down the beach there were sand dunes that gradually rose fifty feet high that we climbed and then threw ourselves down, stumbling and leaping, shrieking and rolling to the bottom. Then we picked ourselves up and walked along the waterline where the sand was wet, and seaweed and shells were washing up on the waves. The water was icy cold but it felt wonderful when I stood still and it eddied around my bare feet as the sand slipped away from under them.

We walked back to where we came out of the woods and built a fire to cook our go-to hiking lunch of hot dogs. Even looking for bits of firewood felt special as we poked around under logs and cut hot-dog sticks from the shrubbery. We sat quietly on a log and stared out to sea while we ate. We were full of the wonder of this place. It was here on this beach that we first talked about getting married.